Home-electrification startup Jetson just raised $50 million to fuel its ambitious effort to slash the cost of installing heat pumps in the U.S. and Canada.

Founded in 2024, Jetson says it can install the ultraefficient appliance for 30% to 50% less than competitors. The company has also developed its own smart heat pump, called the Jetson Air, which it unveiled last September. Currently, the startup operates in its home base of British Columbia, Canada, and in Colorado, Massachusetts, and New York, with over 1,000 heat-pump installations to date.

Jetson’s team, which has grown from 75 employees in September to 120 today, has extensive experience in designing consumer hardware. Co-founder and CEO Stephen Lake previously led smart-glasses startup North, which Google acquired in 2020. Several former North employees have joined Lake to work on home-electrification products.

The infusion of Series A funding will help Jetson continue to grow its team — and its market reach.

Jetson will use the investment to develop other home appliances, find ways to further reduce costs for consumers, and expand into new geographies, Lake said. The company plans to unveil a heat-pump water heater midyear.

As for geographic expansion, Jetson will prioritize regions where “the need for efficient heating is clear,” he said. “We’ll be in Washington state shortly and will be announcing new locations throughout the year.”

Funders flocked to the company in part because Jetson is pursuing “an absolutely massive market,” according to Ryan Gibson, an investor at Eclipse Ventures, which led the funding round. Roughly half the homes across the U.S. and Canada burn fossil fuels for heating, according to government data, and could switch to emissions-free heat pumps.

The market for the heating-and-cooling appliance is ripe for disruption, according to Gibson. The way that heat pumps are traditionally sold and installed is fragmented and low-tech, with little pricing transparency, he said. Contractors typically need to perform assessments in person in order to provide an estimate. By contrast, Jetson provides instant quotes online and at competitive prices that rival the cost of a furnace plus a conventional air conditioner.

On average, a Jetson system costs about $15,000 before local incentives, Lake said. That’s quite a departure from the national average. Using 2024 data, nonprofit Rewiring America estimated that for a medium-size home, a central heat-pump system costs a median of $25,000. (Jetson declined to share whether it’s currently profitable.)

To achieve those lower prices, Jetson takes a vertically integrated approach: from designing its software-enabled and sensor-equipped heat pump to having its own technicians roll up in one of the startup’s green electric trucks to install the appliance in a person’s home. The company also provides ongoing remote monitoring so that it can alert customers to quiet issues, like a dirty air filter that’s eroding performance.

In addition to Jetson, venture capitalists have backed a few other “heat-pump concierge” startups in recent years, though more modestly. Elephant Energy raised $3.5 million in seed funding in 2022; Tetra secured $10.5 million in seed money in 2023; and Quilt, which makes mini-split systems, added to a $33 million Series A with a $20 million Series B round in December.

Jetson’s funding round comes just after the U.S. government repealed a $2,000 tax credit for heat pumps, as well as subsidies for other efficiency upgrades, and as the nation struggles with rising energy bills. This presents a clear opportunity for firms like Jetson, which promise big cost savings over traditional installers. And with the new cash, the startup has a chance to deliver.

New England winters can get wicked cold. This week, five of the region’s states launched a $450 million effort to warm more of the homes in the often-frigid region with energy-efficient, low-emission heat pumps instead by burning fossil fuels.

“It’s a big deal,” said Katie Dykes, commissioner of Connecticut’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. “It’s unprecedented to see five states aligning together on a transformational approach to deploying more-affordable clean-heat options.”

The New England Heat Pump Accelerator is a collaboration between Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island. The initiative is funded by the federal Climate Pollution Reduction Grants program, which was created by President Joe Biden’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. The accelerator’s launch marks a rare milestone for a Biden-era climate initiative amid the Trump administration’s relentless attempts to scrap federal clean energy and environmental programs.

The goal: Get more heat pumps into more homes through a combination of financial incentives, educational outreach, and workforce development.

New England is a rich target for such an effort because of its current dependence on fossil-fuel heating. Natural gas and propane are in wide use, and heating oil is still widespread throughout the region; more than half of Maine’s homes are heated by oil, and the other coalition states all use oil at rates much higher than the national average. The prevalence of oil in particular means there’s plenty of opportunity to grow heat-pump adoption, cut emissions, and lower residents’ energy bills.

At the same time, heat pumps have faced barriers in the region, including the upfront cost of equipment, New England’s high price of electricity, and misconceptions about heat pumps’ ability to work in cold weather.

“There’s not a full awareness that these cold-temperature heat pumps can handle our winters, and do it at a cost that is lower than many of our delivered fuels,” said Joseph DeNicola, deputy commissioner of Connecticut’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection.

To some degree, the momentum is shifting. Maine has had notable success, hitting its aim of 100,000 new heat pump installations in 2023, two years ahead of its initial deadline. Massachusetts is on track to reach its 2025 target, but needs adoption rates to rise in order to make its 2030 goal.

The accelerator aims to speed up adoption by supporting the installation of some 580,000 residential heat pumps, which would reduce carbon emissions by 2.5 million metric tons by 2030 — the equivalent of taking more than 540,000 gas-powered passenger vehicles off the road.

The initiative is organized into three program areas, or “hubs,” as planners called them during a webinar kicking off the accelerator this week.

The largest portion of money, some $270 million, will go to the “market hub.” Distributors will receive incentives for selling heat pumps. They will keep a small percentage of the money for themselves and pass most of the savings on to the contractors buying the equipment. The contractors, in turn, will pass the lower price on to the customers. In addition to reducing upfront costs for consumers, this approach is designed to shift the market by encouraging distributors to keep the equipment in stock, therefore making it an easier choice for contractors and their customers.

These midstream incentives are expected to reduce the cost of cold-climate air-source heat pumps by $500 to $700 per unit and heat-pump water heaters by $200 to $300 per unit. When contractors buy the appliances, the incentive will be applied automatically — no extra paperwork or claims process required.

“It should be very simple for contractors to access this funding,” said Ellen Pfeiffer, a senior manager with Energy Solutions, a clean energy consultancy that is helping implement the programming. “It should be almost seamless.”

Consumers will also remain eligible for any incentives available through state efficiency programs, such as rebates from Mass Save or Efficiency Maine, but will likely not be able to stack the accelerator benefits with federal incentives like the Home Efficiency Rebates and Home Electrification and Appliances Rebate programs.

Program planners expect to be finalizing the incentive levels through the end of the year, enrolling and training distributors in the early months of 2026, and making the first participating products available in February 2026, said New England Heat Pump Accelerator program manager Jennifer Gottlieb Elazhari.

The second program area is the innovation hub. Each state will receive $14.5 million to fund one or two pilot programs testing out new ways to overcome barriers to heat pump adoption by low- and moderate-income households and in disadvantaged communities. One state might, for example, create a lending library of window-mounted air-source heat pumps, allowing someone whose oil heating breaks down the time to research replacement options rather than just installing new oil equipment.

The innovation hub will also include workforce development and training. Organizers are talking with contractors and other partners to figure out where the gaps are in heat pump training. In the first few months of 2026, they will develop a program with a target start date in April.

The goal will be not only to ensure that there are tradespeople with the needed skills to install the systems, but also to lay the groundwork for faster adoption by spreading knowledge about the capabilities of the technology and the available incentives.

The third major area of the accelerator is a resource hub to aggregate information for contractors, distributors, program implementers, and other stakeholders. Overall, organizers hope to have all three hubs operational in spring 2026.

Accelerator planners expect programs to boost adoption even as a federal tax credit of up to $2,000 on heat pumps and heat-pump water heaters is phased out at the end of the year, leaving states leading the way on clean energy action.

“At the state level, this is one example of a way we are helping to make progress in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but with a solution that can help people take control of their energy costs,” Dykes said. “That’s really what we’re focused on.”

DALLAS — Past gnarly live oaks, behind a barbecue joint and a brewery in a suburb north of Dallas, a white-washed brick commercial building extruded its own wispy cloud into the Texas sunlight.

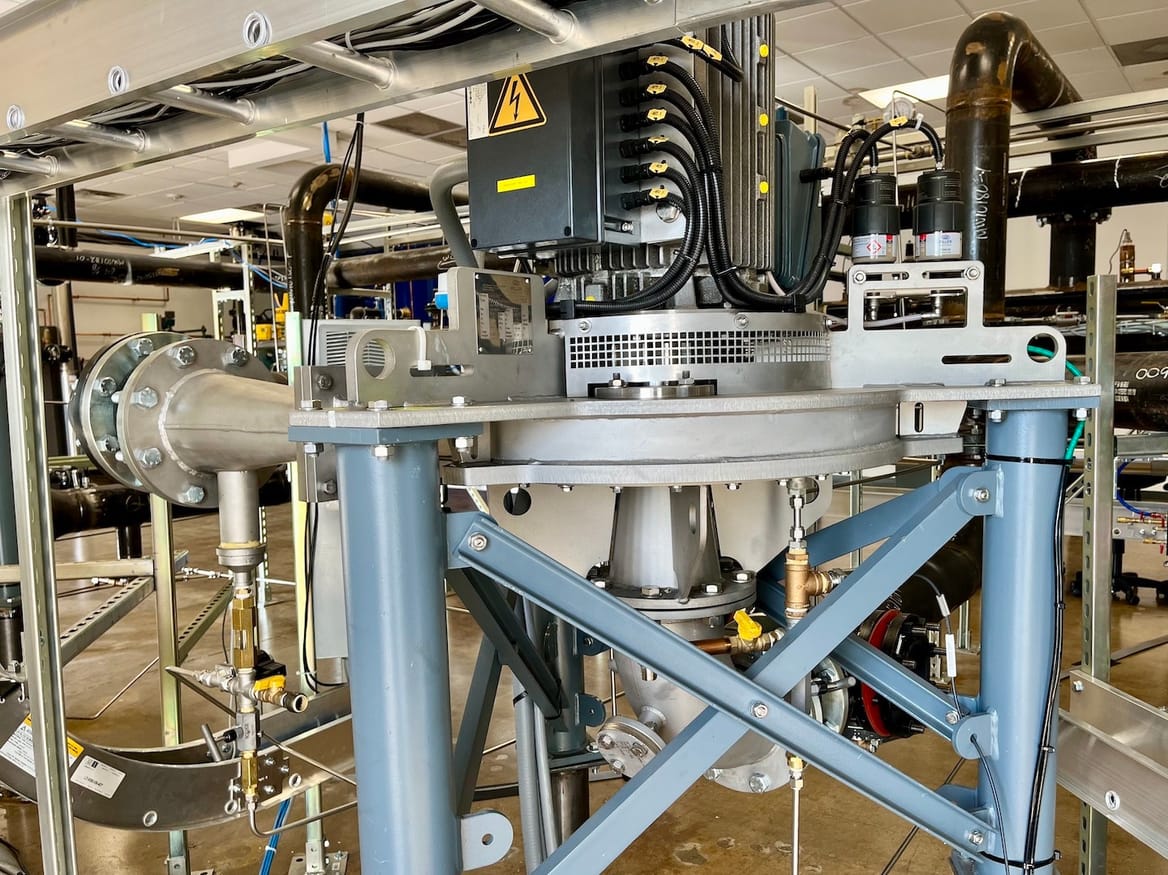

Inside, the startup Skyven Technologies was running a mechanical apparatus dubbed Arcturus, which turns waste heat into industrial-grade steam. It’s so new that I was the first outsider to see the contraption up close — signing my name in slot No. 1 in the log book. But, soon, Skyven will show it off to manufacturers who want to save money on energy bills while cutting their carbon emissions.

Industrial heat causes about 20% of global carbon emissions, per a McKinsey analysis. Very high-temperature processes, like melting ores for steelmaking, are tough to replicate without fossil fuels. But, in Skyven’s analysis, about half of those industrial heat emissions come from making steam, usually in boilers that burn gas or other fuels. Skyven, and a growing cadre of startups, are designing clean, electric, hyper-efficient heat pumps to take over that task.

They have their work cut out for them: Right now, the U.S. is home to about 39,000 industrial boilers, according to Richard Hart, a decarbonization expert at the think tank American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. The steam they generate is used to sterilize injectable drugs, turn pulp into paper, pasteurize milk, cure lumber, and more.

Boilers are reliable and not particularly expensive — and in the U.S., natural gas is cheap — so it’s hard for cleaner alternatives to compete. ACEEE, which tracks announcements of new industrial clean-heat projects, namely heat pumps or thermal batteries, currently registers just 19 completed installations nationwide.

Skyven tackles the tricky economics by focusing on energy savings. The startup installs Arcturus at no cost to the customer, alongside existing gas boilers. The heat pump taps into the factory’s waste heat, which helps it reach high temperatures with far more efficiency than older technologies. Skyven and the customer split the savings from making cheaper electric steam, but if electricity prices spike, Skyven temporarily switches back to the gas boiler to avoid higher costs.

“What we want to do as a business is make industrial manufacturing in the U.S. and worldwide a lot more efficient, by being the leader in upcycling industrial heat and reusing it without having to create it anew,” Skyven founder and CEO Arun Gupta told me.

For now, the steam produced in Skyven’s site near Dallas floats harmlessly into the sky. But with contracts signed and real-world data to share, Skyven is mobilizing for a wave of factory deployments in the years to come.

Arcturus is not something you can pull out of a box fully formed, but a room-sized network of interlocking pipes, chambers, and appliances.

Gupta and Jim Saccone, Skyven’s senior vice president of global sales, handed me earplugs and led me into the clamorous, sun-washed room where the machinery whirred. In one corner sat a conventional gas boiler and a water heater, which acts as a stand-in for the waste source Arcturus will harness in factories.

Arcturus uses a heat exchanger to transfer energy from whatever the source is to a loop of water. While I observed it, relatively cool water from Arcturus hit the heat exchanger and rose from around 67˚C (153˚F) to 92˚C (198˚F). That heated water flows through shiny steel piping into a thick metal vacuum chamber, which lowers the boiling point and swiftly “flashes” the water into steam.

That low-pressure steam then travels through a series of four compressors, all noisily spinning at roughly 15,000 revolutions per minute. Each compressor ratchets up the temperature and pressure of the steam until it hits the target zone, which can be tailored to the needs of each factory.

“Because we make this steam with waste heat that was otherwise going to get dumped, and then just use compressors to compress that steam, that’s much less energy than using the energy to make the steam but not having any compressors,” Gupta said.

The demonstration unit generates 105˚C (221˚F) steam, which runs back through a pipe into the “customer” side of the room. In a real customer setting, Arcturus could sit up to half a mile from the factory where it delivers steam, if space is limited. For now, the vapor just vents through the roof.

The demo system produces up to 1 megawatt of thermal output. Skyven has already signed deals in the 10- to 15-megawatt-thermal range — these will have a similar footprint, Gupta said, but use bigger pipes and compressors. The technology can heat steam all the way to 215˚C (419˚F) if needed; that’s unusually high for industrial heat pumps, which typically reach around 170˚C (338˚F).

Since Skyven is producing real heat now, it has established an empirical baseline for its operating efficiency. The term of art here is “coefficient of performance,” which measures how much energy is produced per unit of energy consumed.

Gas boilers score 0.83, Saccone said, losing some energy along the way. Electric resistance boilers, a commercially mature electric heat technology, hit close to 1, a near-complete transfer of energy into heat. Startup AtmosZero recently installed an air-source industrial heat pump at New Belgium Brewing in Colorado that can reach 165˚C (329˚F); that device sports a COP of around 2.

Skyven’s average measured COP for its pilot is 6.5, but Gupta said he aims to raise it to 8 within the next three months. This isn’t a fixed value: It depends on factors like how hot the waste source is and how hot the steam needs to get. The demo site nonetheless establishes a real-world high water mark of how efficient Arcturus can be.

“The higher that [COP] value goes, the less important the spark gap is going to turn out to be,” said Hart, referring to the gap between power and gas prices. If, for example, a unit of electricity costs twice the equivalent in gas, but produces six or eight times the heat, then the heat pump is cheaper to run than a gas boiler.

Gupta didn’t set out to invent an industrial heat pump.

He had been working at Texas Instruments’ digital-light-projection business, designing the chips that run most every digital movie-theater projector. He wanted to do something good for the world and was concerned about climate change. “So, I was skimming ARPA-E research papers, as one does,” Gupta recalled, as we noshed on burgers up the road from Skyven headquarters.

The Department of Energy’s ARPA-E funds research on potentially transformative technologies. That archive was where he hit on the challenge of clean industrial heat; he figured, with his expertise manipulating light, he could make a better solar-powered heat source.

Gupta founded Skyven in 2013. At first he just tinkered in his Dallas garage, for a while confined to a wheelchair by a calamitous motorcycle accident. Eventually, he moved to the Dallas Makerspace and raised pre-seed financing for his concept. But the sheer amount of insulated plumbing needed to distribute the solar thermal heat wrecked his project economics.

“I made the mistake of a classic technical founder, in that I had a technology that I thought solved the market problem, but I didn’t really validate the market problem,” he explained. Still, he didn’t want to give up on his goal.

“At the time, no one knew anything about industrial heat,” Gupta said. The cleantech industry had spawned plenty of companies that could sell solar electricity to commercial customers, but hardly any solutions for heating needs at factories.

So Skyven reoriented around developing and financing energy-efficient upgrades for industrial heat using the best available technologies. The startup raised seed funding for this tech-agnostic model and landed a breakthrough deal with California Dairies, Inc., the largest dairy co-op in the Golden State.

The mission was to reduce gas combustion, saving money and carbon emissions, at major dairies in Turlock and Visalia. Skyven did this by deploying three types of equipment at each site: solar thermal to generate clean heat, smart steam traps to monitor steam loss in the existing system, and apparatuses to recover heat from boilers.

Skyven bundled $9 million in grants from the California Energy Commission with utility incentives from Pacific Gas & Electric and Southern California Gas Co., and landed project financing from Kyotherm, a French lender for clean-heat projects. With that combined funding, Skyven installed the equipment at no up-front cost to the dairies, and then as the facilities reduced their gas consumption, split the cost savings with them. The dairies could see a metered readout of the avoided gas combustion, and they paid Skyven an agreed-upon portion of it.

Installation wrapped up in 2023. The interventions, still operating under 10-year service contracts, are cutting 7,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide annually by avoiding over 110,000 million British thermal units of natural-gas combustion, more than originally anticipated. But Skyven concluded that the commercially available solar thermal panels weren’t a competitive source for heat, reporting to the California Energy Commission that a steam-generating heat pump would be “a more effective decarbonization solution with a wider appeal.”

Around that time, Gupta said, Skyven was scoping out a deal for an ethanol company in the Midwest. The team came across a bare-bones case study from a European ethanol plant that had built something called an “open cycle mechanical vapor recompression” device — machinery that takes waste heat, compresses and heats it, then recirculates it into the plant.

The problem was, outside of that European plant’s in-house engineering team, “there’s really no one in the world that knows how to implement this,” Gupta said. Skyven tried hiring a third-party engineering firm to draw up designs for the Midwestern customer, but that proved unsatisfactory. “We then said, ‘Okay, what if we built that experience and expertise and essentially invented this system in house?’”

Having learned from his early missteps, Gupta first vetted the idea with a slew of potential customers, who responded enthusiastically. Then Skyven stopped its tech-agnostic deals and staffed up on engineers, drawing on millions of dollars of revenue from the dairy projects. The company’s task, Gupta said, was to take existing steam compressors and adapt them into a heat pump that can be easily inserted into “an actual manufacturing facility with all the intricacies and challenges.”

Now that process has concluded, as evidenced by the steam billowing into the blue Texas sky. And Skyven did all that having raised just $11 million in outside investment and having generated real revenues, quite the outlier for Silicon Valley-backed cleantech.

A functional, highly efficient industrial heat pump is just table stakes. For Skyven to succeed, it must fight an uphill battle convincing big, old companies to bet on new technology. That’s why the startup designed its product and deal structure to minimize risk for the customer.

Arcturus can be assembled without interrupting factory operations, so customers don’t have to sacrifice production time to get the benefits of clean heat. Then Skyven schedules the steam and water connections to coincide with the plant’s regular maintenance shutdown. If that’s not possible, workers can perform a “hot tie-in” to connect Arcturus without stopping factory operations.

Skyven only runs the heat pump when it’s less expensive than using the legacy heat source. This entails real-time algorithmic calculations based on the price of electricity, the price of gas, and the COP. Company software toggles back to the original gas boiler in moments when power prices surge; if Arcturus is running, it’s got to be saving money compared to burning gas, with a target of at least a 30% reduction in cost.

This arrangement means that factories don’t have to pony up millions of dollars up front to decarbonize their heat.

“You can spend your dollars on stuff that’s core, like expanding production or improving quality or rolling out a new product line, and you can still hit your sustainability goals,” Gupta said.

Facilities teams that partner with Skyven can even tell their bosses that they’ll reduce their future operating budgets through the savings from electric heat, Saccone said.

Skyven is able to offer no-money-down steam with the ongoing financial support of Kyotherm, which financed the waste-heat collectors Skyven put into the two California dairies. Now, Kyotherm has signed an agreement whereby Skyven pitches Arcturus installations, and Kyotherm agrees to finance ones that clear its performance thresholds.

“You cannot give a blank check; you need to look at each different project,” said Remi Cuer, Kyotherm’s investment and business development director.

Kyotherm expects high single-digit internal rates of return; that’s more than solar or wind farms would pay, because emerging heat tech carries more risk. But assuming Skyven keeps bringing attractive projects, it can expect project financing for quite some time. Cuer declined to name a specific cap on the agreement but suggested his firm could fund a few hundred million dollars of Skyven installations.

Financiers usually run away from new technology until several of their peers have vetted it. But Kyotherm wasn’t afraid to back Skyven despite the newness of Arcturus. Cuer attributed that assurance to having seen how the team worked on the dairy installations. The Dallas-area pilot project is “really important for us,” he added, so his team can review the logs of COP, uptime, and other key metrics.

“It’s a market, heat pumps, where there are a lot of [original equipment manufacturers] and perhaps, currently, not enough project developers,” Cuer mused.

Until a few months ago, Skyven had a surefire tool for getting its first customer-oriented Arcturus installations done: It had won $145 million from the DOE, part of a $6 billion Biden-era effort to decarbonize heavy industry.

The Trump administration canceled Skyven’s fully contracted grants along with many others in a legally dubious effort to roll back binding federal commitments for clean energy.

“The loss of certainty on the $6 billion from the DOE’s Industrial Demonstrations Program is a challenge for the recipients. They are all considering next steps,” Hart said. But even where the money is gone, the knowledge and corporate buy-in required to win those grants lives on. The grantees “had to really think about how to do this technically, how to bring the right partners together, get the plants excited about the idea, and do all of that due diligence as part of their submissions,” Hart said.

Most other companies losing those grants boast far greater balance sheets, like Kraft Heinz and Diageo. Skyven, a much smaller company, is pursuing an internal appeal within DOE, and not currently seeking legal recourse, Gupta said.

“The cancellation of the funds has not killed the projects,” Gupta said. “They are actually all still moving forward, they’re just moving forward a lot slower.”

The plan had been to build a slew of them and learn from the results to drive costs down. Instead, Skyven slowrolled development to grind out system-cost reductions, so the projects would still make financial sense without government support. This effort went surprisingly well, Gupta reported, and pushed costs 40% lower in just a few months.

Skyven once again has had to zig and zag, improbably emerging stronger from the turbulence.

President Donald Trump’s megalaw will soon slam the door on tax credits for homeowners who want to install heat pumps or make other energy-efficiency improvements.

But there’s still one way to tap federal assistance for cleaner heating.

The same law allows installers of geothermal heat pumps and systems that store thermal energy for later use to earn tax credits for years to come. Though individuals can’t tap the incentives directly, companies that retain ownership of the systems can lease them to customers at a cost that reflects the federal discount of 30% to 50%.

Already, some companies are adapting to the new state of play. Installers that didn’t previously have a leasing business are pivoting to take advantage of the incentives. For firms that already deploy thermal energy storage systems in multifamily buildings via commercial partners, the transition is especially straightforward.

It’s a rare and under-the-radar bright spot for home electrification in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). The law is otherwise expected to slow down the shift from fossil-fueled buildings to heat pumps, which improve air quality and can save consumers money on top of reducing carbon emissions. But the pathway available to companies that lease geothermal and other clean-heat systems could help soften the blow.

Take Dandelion Energy, a startup specializing in home geothermal heat pumps that pull warmth from the ground rather than the air. Already, the firm has launched a leasing structure to take advantage of the changes.

If anything, the new law has made Dandelion’s approach to earning tax credits simpler, said CEO Dan Yates. That’s because the Google X spinout has in the past few years “focused on working with large-scale new homebuilders, where we do hundreds, even thousands of homes in new projects,” like its sizable partnership with homebuilder Lennar in Colorado.

Homebuilders didn’t have a clear way to capture the value of geothermal heat pumps under the Section 25D tax-credit program that’s going away at the end of this year, Yates explained. That tax credit was for households, not for companies that build homes with the eligible technology.

But under Dandelion’s new leasing structure, homebuilders can capture the baseline 30% tax credit, plus a 10% adder under domestic-content provisions that Dandelion’s U.S.-built systems qualify for. That enables them to save “thousands of dollars” up front, Yates said. “In many states, we’re seeing this lease as a real tipping point, where geothermal becomes less expensive than the status quo for the builders.”

The changes in the OBBBA also solved a key problem for third-party ownership of geothermal heat pumps, he said. Under previous tax-code language, those systems were considered “limited-use property,” meaning that the commercial owner couldn’t repossess them if the leaseholder failed to make payments, which complicated leasing structures.

But the Geothermal Exchange Organization, a geothermal-heat-pump trade group, successfully lobbied to change that language with the OBBBA. Now, leased geothermal systems can enjoy the same tax credits that have helped boost larger projects such as geothermal district-heating networks, which supply ground-source heat to buildings, campuses, or entire neighborhoods.

Dandelion’s leasing partner is Upstream Lease, a division of Carbon Solutions Group, which has previously specialized in monetizing tax credits for distributed energy systems like rooftop solar. Third-party lease and power purchase agreements make up roughly half of the U.S. residential rooftop-solar market to date, and remain available, at least in a truncated form, under the OBBBA.

Keith Martin, an attorney with law firm Norton Rose Fulbright and an expert on clean-energy tax equity, said his firm is working on geothermal-heat-pump leasing and tax-credit monetization strategies similar to those undertaken by Dandelion and Upstream, though he declined to name the companies involved.

“They’re looking at retaining ownership, just like the solar rooftop companies do, and then packaging large groups of heat pumps and arranging tax equity as a way of monetizing the tax benefits,” he said.

Companies can continue to claim geothermal-heat-pump tax credits for projects that start as late as 2034, Martin said.

As for the cost to homeowners, Yates said the typical payments add up to $150 to $200 per year, a “tiny” amount compared to typical rooftop-solar lease payments that can be as much every month. And the superefficient nature of ground-source geothermal can cut a home’s energy bills by $500 to $900 per year, or two to four times as much as they’re paying for a system that can last decades.

“That’s what we love about this — it really does align everybody’s interests,” he said.

The other class of household heating and cooling equipment that received a reprieve from Republicans in the OBBBA is thermal energy storage systems. The term typically describes large-scale systems that use energy to generate heat or cold, which is stored for later use — a class of technologies that range from industrial-scale heat batteries to massive chilled-liquid networks connected to multiple buildings.

But homes and apartments can also benefit from smaller-scale versions of these systems, which are eligible for full tax credits until 2033 and then for gradually reduced tax credits through 2035 under the OBBBA.

For Jane Melia, co-founder and chief revenue officer of Harvest Thermal, that opens up opportunities.

Her company makes the Harvest Pod, a device that uses a heat pump to warm both water and air, and also stores that heated water for later use. That allows households to use electricity when it’s cheap and plentiful to heat water, which can be tapped later when power prices are higher. Under the OBBBA, devices that can store enough energy to heat and cool a building for at least one hour qualify for tax credits.

Of course, those tax credits are also only available to companies, not consumers, under Section 48E of the tax code, she said. But lease structures for household heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems are relatively common, she said. “If they’re willing to lease the HVAC equipment, then the leaseholder captures the tax credit, and it flows through to making the lease payment lower than it would otherwise be.”

For single-family homes, “that’s something we’re actively working on to get it in place in 2026,” she said. “It’s not done yet. But I think that’s where the industry is going.”

Multifamily buildings are even better suited to capture tax credits for third-party-owned thermal storage systems, since the owners of properties are stand-ins for commercial leaseholders. In fact, Harvest Thermal has already seen some of its devices capture the 48E tax credit in a multifamily project in Truckee, California, a mountain town where efficient electric heating with storage can make a significant dent in energy costs.

“This project would not have happened without the tax credits,” said David Chanin, cofounder of FutureFit Partners, the company that managed the installation of eight Harvest Pods in a 72-unit low-income housing site in Truckee. The owner of the building was able to reimburse 40% of the project cost through tax credits, including the 30% base credit and a 10% adder available for projects in “energy communities” that have historically relied on fossil-fuel extraction and production.

The challenge with these large-scale projects is that companies might not have enough tax liability to capture the full value of the tax credits for the various projects they’re doing. Some firms are dealing with this constraint via a financial tactic called transferability, which lets them sell those tax credits to a bigger entity for cash.

In the case of the Truckee project, for example, the building owner sold its credits to a financial partner that wanted to offset its tax bills, Chanin noted.

Not all property owners are prepared to handle the legal and accounting tasks of turning tax credits into project finance, however. Those that fall into this bucket can turn to the commercial entities that aim to facilitate this process.

Take Kelvin, a New York City-based startup that has partnered with ClearGen, an energy-infrastructure investor owned by real-estate giant CBRE Investment Management, to structure some of its first tax-credit transactions.

The startup makes a device called the Cozy that fits over radiators that heat a lot of older buildings, captures the warmth they generate, and lets it out into rooms over time using software controls.

“We’re putting insulated radiator covers over 300 pounds of cast iron. When you heat that up, it’s actually an extraordinarily large thermal battery,” said Kelvin CEO Marshall Cox. That makes the Cozy eligible for tax credits under the OBBBA — as long as it’s owned by a third party.

Kelvin already offers its Cozy to building owners “on a subscription basis, just like solar finance,” Cox said. But ClearGen is helping it expand the scale of these kinds of agreements. “They have very large buyers” of tax credits “that they work with,” he said.

The startup has also monetized credits for a New York City project with the help of Giraffe, one of a growing number of companies that help owners of tax-credit-eligible projects find buyers for the incentives.

Identifying ways to turn the theoretical value of tax credits into real-world project financing isn’t simple, Melia said. But it’s important to expand the market for these technologies to households and buildings that would otherwise struggle to afford them.

“This is, first of all, a way for multifamily properties — low-income and high-income — to benefit,” she said. “But it’s also a way for the business model to evolve.”

A correction was made on Nov. 3, 2025: This story originally misstated Jane Melia’s title at Harvest Thermal. Melia stepped down as CEO to take on the role of chief revenue officer in April 2025.

In the depths of the 75-year-old Kendall Cogeneration Station along the Charles River in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a clean-heating transformation is underway.

For years, the facility has burned natural gas to produce steam for Boston and Cambridge’s century-old underground heating system. Now, it’s aiming to become a clean “district energy” system, capable of delivering warmth during bitter New England winters without baking the planet — a first for a citywide network in America.

Last year, Vicinity Energy, the owner and operator of the steam heating network, finished installing a 42-megawatt electric-powered boiler at the Kendall facility. Earlier this year, the company confirmed plans for its next step: installing a 35-megawatt industrial heat pump from Everllence, a German energy systems manufacturer formerly known as MAN Energy Solutions.

“That project was greenlit this summertime,” Vicinity Energy CEO Kevin Hagerty told Canary Media, and demolition to make way for the new heat pump has already begun.

“We’re anticipating that being completed midway through 2028. We’ll turn the heat pump on and turn the Charles River into a renewable energy resource,” Hagerty said.

The industrial heat pump will draw from the river water’s latent thermal energy to create boiling-point temperatures within the Kendall facility’s steam-generation complex. The technology will function even in the winter because the low-temperature refrigerant it uses is far colder than even the icy-cold Charles, creating a temperature differential that the heat pump can harness to produce steam.

All that steam flows through about 25 miles of piping to heat roughly 70 million square feet of buildings in Boston and Cambridge, including college campuses and biotech facilities. Vicinity has secured commitments to use the lower-carbon steam from its electric-powered heating systems from area customers such as Emerson College and life sciences real estate company IQHQ.

Hagerty said other “very large offtakers are underwriting this,” although he declined to name them. “The pump is not fully subscribed yet, but it’s getting there.”

The system will be among the biggest in the United States, which has roughly 900 district energy systems ranging from those in airports and on college campuses to the citywide steam network in Manhattan, the country’s oldest. District heating is also popular in European cities, where comparatively high fossil-gas prices are driving a more urgent embrace of large-scale clean-heating systems.

For customers in Cambridge and Boston, Vicinity’s “eSteam” plan makes sense for reasons of political economy, Hagerty said. Massachusetts has set mandates to expand its supply of carbon-free electricity and to reduce its use of fossil fuels in buildings. A preexisting, centralized system like the Kendall facility’s can convert to electric heat pumps and boilers far more cost-effectively than individual buildings could on their own, he said.

“It’s about one-half to one-fifth the cost for buildings to use our eSteam and electrify through the district energy system than it is for them to locally electrify and decarbonize,” Hagerty said.

Most of those savings come from the fact that the Kendall facility’s electric grid substation and steam pipe network are already built, he said. That obviates the need to retrofit individual buildings with electric heating — or for utilities to make distribution grid upgrades to accommodate a heat pump at every building.

District energy systems like Vicinity’s also benefit from economies of scale, Hagerty said. Large, centralized networks can mix and match mutually reinforcing technologies like electric boilers and heat pumps. They can recapture waste heat from other parts of the system and use it to make more steam, as is being done with the Kendall facility’s gas-fired electricity-generation turbine, which provides peak power and “black start” services for the local grid.

District energy systems can also store and shift energy, as Vicinity plans to do with the thermal energy storage that makes up the next stage of its eSteam conversion plan. It’s looking at systems that can convert electricity into heat storage, which would “allow us to relieve the stress on the electric grid and be a lot more flexible,” he said.

If anything, the Boston-Cambridge system is only starting to utilize the cost-effective decarbonization strategies that district energy systems enable, Hagerty said. Europe is leading the way on that front, with showcase projects such as the 70-megawatt industrial heat pumps now using the chilly water of the Baltic Sea as a thermal exchange to heat water to keep buildings warm in the city of Esbjerg, Denmark.

“They currently have the largest industrial-scale heat pump for district energy in the world,” said Alejandro Gorosito, U.S. national sales manager for Everllence, which provided the heat pump for the Danish city. It won’t hold that distinction for long, he said — Everllence is building a 150-megawatt heat pump for a similar project in Cologne, Germany.

In Europe, adoption of industrial heat pumps is helped along by the fact that fossil fuels tend to be more expensive than electricity. Because heat pumps are far more efficient than fossil-fueled options, they can be the most cost-effective choice when electricity is cheaper, Gorosito said — a fact that can push companies without climate goals to pursue the clean-heat technology.

In much of the United States, where fossil fuels are abundant and power prices are rising fast, the math doesn’t favor heat pumps, Hagerty conceded. But for Boston and other cities that require building owners to reduce their carbon emissions, and for states like Massachusetts that aim to decarbonize their economies, district energy systems can serve as a “regulatory hedge for our customers,” he said.

“They need to make decisions as to whether or not they’re going to heat their building with natural gas, because we’ve got regulations in place that are going to start enacting fines … Do they want to take the risk of spending millions of dollars on something that they may not be able to use in five to 10 years?”

Massachusetts heat-pump owners will spend less to stay warm this winter, thanks to an innovative policy going into effect this weekend.

The state’s three investor-owned electric utilities — Eversource, National Grid, and Unitil — are all offering lower winter rates to the roughly 100,000 households with electric heat pumps, starting on Nov. 1 and running through April.

“It really is what matters to people — it reduces the cost of running a heat pump,” said Larry Chretien, executive director of the Green Energy Consumers Alliance, who is replacing his own gas-fueled heating system with heat pumps this week.

Massachusetts is the first state in which all the major utilities are offering these savings. The rates — ranging from 4.3 cents to 7.5 cents per kilowatt-hour lower than the standard winter price — could trim from $70 to $140 per month off the average bill, utilities estimate. The lower rate applies to all electricity used by participating homes during the winter months.

Households that received heat-pump rebates from state energy-efficiency program Mass Save since 2019 will be automatically enrolled in the new rate. Residents who installed heat pumps earlier or didn’t work with Mass Save can contact their utility to receive the lower rate.

Massachusetts, like other states with ambitious climate goals and cold winters, has made heat-pump adoption a key part of its decarbonization strategy. Today, more than half the homes in the state use natural-gas heating, and another 25% burn heating oil or propane. More than 90,000 homes installed heat pumps from January 2021 to July 2024, but annual adoption rates will need to double over the next five years if the state is to hit its goal of getting the systems into 500,000 homes between 2020 and 2030.

The cost of installing and operating heat pumps has traditionally been a major barrier preventing people from making the switch, particularly in Massachusetts, where electric rates are among the highest in the country. Under current default rates, just 45% of households that transition to air-source heat pumps — the most common version of the appliance — would save money on heating each month, according to a study from climate-policy think tank Switchbox.

Seasonal heat-pump rates change that calculation. Eligible customers will be charged a lower rate on the delivery portion of their bill, while power-supply rates will remain the same. That means that customers who buy power from a third-party supplier or through a municipal community choice program can still participate.

The result should be more savings for more people. Factoring in the discounts, Switchbox estimates roughly two-thirds of households switching to heat pumps would see lower bills, with average monthly savings of $90. The lower cost of operation should make heat pumps a feasible financial choice for more residents, Chretien said.

“This will just put wind in the sails of the heat-pump market,” he said.

Proponents of heat-pump rates say the lower prices are not being subsidized by other customers. Instead, the new approach is a “right-sizing” of currently inflated winter rates.

The delivery portion of a utility bill pays for the poles, wires, transformers, and other infrastructure needed to, well, deliver power. The rate is determined, roughly, by adding up these costs and dividing the total by the number of kilowatt-hours the utility expects customers to use. That number, plus an allowed rate of return for the utility, becomes the final rate.

The grid infrastructure is built to handle moments of peak demand, typically those hottest of summer days on which millions of air conditioners turn on at once. In the winter, demand usually reaches no more than 80% of the highest summer levels, meaning plenty of capacity is left unused.

In other words, the grid already has the room to accommodate winter demand from heat pumps, so no expensive upgrades are required. Therefore, it would be unfair to ask the heat-pump owner to pay more when they aren’t adding more cost, supporters say.

And while the lower rates can save consumers money, they shouldn’t cut into utilities’ revenue, as the increased use of electricity offsets the decreased price per kilowatt-hour.

“We could see heat-pump rates as leveling the playing field,” said Amanda Sachs, state policy manager for electrification advocacy group Rewiring America.

This winter’s lower rates may be just the beginning for Massachusetts residents. The state energy department in January asked utility regulators to mandate even steeper discounts, ranging from 12 cents to 17 cents per kilowatt-hour, for the heating season starting in November 2026. With these much deeper cuts, 82% of households switching to heat pumps would end up paying less for winter heating, with a median annual savings of $687, according to the Switchbox analysis.

Seasonal heat-pump rates are not meant to be a long-term strategy. The logic underpinning the rates only holds so long as peak demand happens in the summer, and the New England grid is expected to shift to a winter-peaking system in the 2030s. By then, though, utilities should have rolled out advanced meters that will allow more sophisticated and nuanced rate structures to replace current models.

“We’ll be able to be way more accurate about heat-pump usage,” Sachs said.

Boston is racing to decarbonize its public housing by 2030. The latest tool it’s deploying to reach that goal? Window-straddling heat pumps.

Last week, the Boston Housing Authority announced that it’s piloting the electric technology at Hassan Apartments, a 50-year-old public housing community with 100 units for older people and adults with disabilities. The modular appliances, made by California-based startup Gradient, plug into a typical 120-volt wall outlet and will replace the apartments’ outdated, much less efficient electric-resistance system.

“We believe that low-income people and the families and individuals who live in our buildings deserve access to 21st-century technologies and home comforts, just like anyone else out there,” said Joel Wool, the agency’s deputy administrator for sustainability and capital transformation. “We’re also doing our part to reduce air pollution and combat climate change.”

The Boston Housing Authority has ordered about 100 window heat pumps for the project. Two other Massachusetts housing agencies are also piloting Gradient’s appliances, the company announced last week: the Chelsea Housing Authority, which is testing about 400 heat pumps, and the Lynn Housing Authority & Neighborhood Development, which is trying out roughly 200 heat pumps, about half of which are already installed.

Outside of Massachusetts, in 2022, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) committed to purchasing a total of 30,000 of the devices from Gradient and global appliance maker Midea over a period of seven years. The agency has been learning from an initial 72 heat pumps installed, and their performance has been positive enough that Gov. Kathy Hochul (D) announced on Friday $10 million to fund demonstration projects statewide.

Heat pumps, which are essentially reversible air conditioners, are key to electrifying heating. They provide potentially life-saving cooling, too. Because they shift around ambient heat instead of generating it anew, the appliances are routinely two to four times as efficient as electric-resistance and fossil-fuel-fired options. (Gradient claims its heat pumps are also about 50% more efficient than plain old window AC units.)

But retrofitting a building with a conventional heat-pump system can be a complex undertaking, requiring electrical upgrades and new refrigerant lines that run to individual air-handling units in each apartment, for example. Window heat pumps might require some trade-offs in terms of efficiency, but they also sidestep those serious installation hurdles.

That ultimately makes them faster and cheaper to deploy, as well as less disruptive to tenants, according to Wool. Two workers can install one of Gradient’s 140-pound heat pumps in about half an hour, NYCHA estimated, draping its saddle shape across a windowsill. And a July study by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy found that window heat pumps are typically the lowest-cost option for efficiently decarbonizing space heating, coming in at an average lifetime cost of about $14,500 per apartment compared to between $22,000 and $30,000 for large-scale heat-pump systems.

For its pilot, the Boston Housing Authority is paying $5,450 per residence to retrofit with window heat pumps — about one-eighth of what it has spent to update other buildings with conventional heat-pump systems: approximately $40,000 per unit, according to Wool.

Electric and gas utility Eversource is fully funding the project through the state’s energy-efficiency collaborative, Mass Save. Once the retrofit’s complete, the Boston Housing Authority expects to save up to $60,000 in energy costs per year.

In New York, window heat pumps are already making deep cuts to energy use. At the NYCHA-owned Woodside Houses, going from a gas-powered steam system to the appliances slashed the amount of energy consumed for heating by 85% to 88%, according to preliminary results from NYCHA.

“This [reduction] sounds unrealistically large,” said Vince Romanin, founder and chief technology officer at Gradient. But “we roughly know the reasons.” Waste abounds with fossil-fuel systems: Boilers don’t perfectly convert fuel into heat, steam leaks on its way to apartments, and residents, lacking control over the temperature, are prone to throw open windows if they’re overheating, he noted. User-controlled window heat pumps avoid all of those issues.

Gradient has raised more than $31 million in venture funding and signed over $9 million worth of federal and California grants to develop its window heat pumps, which it has shipped to multifamily building owners and developers in 18 states, Romanin said. He declined to specify the cost per unit.

At the Hassan Apartments in Boston, installations are already underway and should wrap up by mid-November, said Wool of the city’s housing authority. The agency will monitor energy costs closely, as it weighs whether to deploy the tech at other properties. Across its 10,000-unit portfolio, heat pumps — of the conventional variety — serve just a few hundred apartments so far.

“We do think that window heat pumps are a great technology,” Wool said. “It’s also still an early one. We want to see how it performs.”

LOVELAND, Colo. — For a moment, I held in my hand the cool heart of a heat pump.

I was standing inside the cavernous facility where the startup AtmosZero is building its novel steam-producing heat pumps. The all-electric technology is meant to replace the gas-burning boilers that factories rely on to make everything from Cheez Whiz to notepaper to beer. I visited the 83,000-square-foot plant on a sunny September morning to learn how AtmosZero is working to make industrial heat — but without the planet-warming carbon emissions.

The grapefruit-sized component I grasped, called a compressor wheel, helps to produce the heat that’s needed to make steam with AtmosZero’s tech, Todd Bandhauer, the startup’s chief technology officer and cofounder, explained from the factory floor.

AtmosZero opened the facility, once a mothballed Hewlett-Packard electronics plant, earlier this year to begin commercial production of its Boiler 2.0, a machine the size of a shipping container that can be hoisted by crane and plunked inside another factory.

The company has big ambitions for its electrified solution. In the United States, around 40% of the fossil fuels that factories consume is burned in boilers to make steam for processes including sterilizing equipment, breaking down wood chips for papermaking, and cooking, curing, pasteurizing, and drying food.

“Steam is the most important working fluid, both in industry and the built environment,” said Addison Stark, the startup’s CEO and cofounder. “The boiler is what drove the Industrial Revolution.”

AtmosZero spun out of Bandhauer’s research at Colorado State University in 2021, and it has since raised nearly $30 million from investors and $3.2 million from the Department of Energy to realize its steam-heat dreams. In June, the startup finished installing a 650-kilowatt pilot unit at the New Belgium brewery in Fort Collins, Colorado. At the Loveland facility, the company is working to build and deliver its first commercial heat pumps by around 2026.

The factory floor was quiet when I visited last month, with custom-made parts in open boxes or on pallets awaiting assembly. But Stark said he sees the facility getting much busier as the company works to fill demand from potential buyers, who face increasing pressure from state regulators and their own customers to slash gas-related pollution.

“I want to see electrification [across] industry and actually get ourselves on track to get to the emissions reductions that we all want to see in this century,” Stark said. In his view, “The only path to that is steam decarbonization.”

Industrial heat accounts for about 13% of U.S. energy-related carbon emissions. Much of that comes from burning fossil fuels in boilers to produce steam, though a small fraction of factories have adopted electric-resistance boilers instead. These machines can at most be 100% efficient, meaning that all the energy that goes into the boiler comes out as heat.

Heat pumps, by contrast, move heat instead of making it. The appliances use electricity and a refrigerant to gather thermal energy from someplace else — say, the open air or a water pipe — and concentrate it using a compressor to deliver the heat where it’s needed. This process can be 300% to 400% efficient or higher.

AtmosZero and a handful of other manufacturers are developing new heat pumps that will allow the technology to replace an even larger share of gas-fired boilers in factories.

Existing heat-pump models can churn out heat up to about 160 degrees Celsius (320 degrees Fahrenheit) — hot enough to cover roughly 44% of industrial process-heat energy, according to a 2022 report by nonprofit American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, or ACEEE. New designs are expected to reach up to 200˚C (392˚F), addressing about 55% of factory heat needs.

“Being able to meet more than [half of] of industrial heat demand with a single technology is really impactful,” said Ruth Checknoff, senior project and research director at the Renewable Thermal Collaborative, a coalition of organizations working to decarbonize process heat and buildings.

At the AtmosZero factory, Bandhauer broke down how the Boiler 2.0 delivers more than hot air.

The compressor wheel I held had precisely sculpted blades that swept out in a tight spiral. When secured in the heat pump, a motor spins the wheel at up to 30,000 rotations per minute, throwing heat-carrying vapor against the equipment’s chamber walls. That increases the pressure, making the vapor hotter. AtmosZero’s heat pump utilizes two of these compression cycles, a kind of one-two punch, to ramp up the temperature enough to boil water.

Then, voila: You have steam as hot as 165˚C (329˚F).

Still, for all the apparent benefits, industrial heat pumps on the market today have struggled to gain widespread adoption. To start, they’re more expensive to install than gas boilers, which can last for decades — limiting the business case for replacing them. In the United States, fossil gas has historically been cheap enough in many places that a boiler has cost less to run than a heat pump, even though the latter uses a fraction of the energy.

States like California, Colorado, Illinois, New York, and Pennsylvania are adopting policies to help address these hurdles. That includes incentives for manufacturers to invest in tech that slashes emissions, air-quality regulations that limit pollution from their operations, and cheap financing for capital-intensive decarbonization projects. Advocates are also pushing states and utilities to work together to set more favorable electricity rates for factories.

Despite the technology’s high price tag, heat pumps can deliver significant savings on factory owners’ utility bills, according to ACEEE. A heat pump’s payback time — the amount it takes to recoup savings equal to the added installation cost — can be just a handful of years.

“We should invest time and energy into making sure that we have the right policies and enabling conditions to deploy [heat pumps] at scale,” Checknoff said.

AtmosZero isn’t the only company making steam-producing heat pumps. Other manufacturers — including GEA, Karman Industries, Heaten, Piller Blowers and Compressors, and Skyven Technologies — are proving out the tech, and some are starting to install their own machines in factories in the U.S. and Europe.

These systems often supplement existing fossil-fueled boilers by capturing a plant’s excess heat that would otherwise be wasted. That approach helps maximize a heat pump’s efficiency: Since the waste heat is already toasty, it’s easier for the tech to turn that into even higher-temperature heat for making steam.

Customers often want to actively harness this throwaway warmth to keep electric bills as low as possible, Checknoff said. But because every facility is different, installing a heat pump to slurp up that thermal energy can be costly and cumbersome.

AtmosZero is aiming for economies of scale, similar to how solar panels and home heat pumps are mass-manufactured and deployed in a modular way. “We want to bring that to the steam boiler,” Stark said during my visit.

The startup’s heat pump can be installed in a day, requiring only hookups to electricity and water lines and the factory’s control system. It’s as simple as replacing an old gas boiler with a new one, he said. And at New Belgium’s brewery, putting in the pilot heat pump this spring didn’t disrupt operations.

“They were able to continue to brew beer,” Bandhauer added.

AtmosZero’s product does have a key trade-off: It’s not as efficient as heat pumps that competitors install to harness waste heat. Those systems produce more heat with the same amount of energy. That ability is measured with what’s called the coefficient of performance, or COP. Whereas other companies’ installations might render a COP of seven or more, AtmosZero’s heat pump has a COP of up to roughly two.

But the Boiler 2.0 is cheaper to install, costing about one-tenth to one-fifth the expense of integrating a waste-heat system, Stark said. He estimated that the savings on the installation costs should enable AtmosZero’s projects to pencil out financially in five years or less.

At his desk inside the AtmosZero factory, a young engineer named Mason Mollenhauer pulled up on his computer screen a rendering of the 650-kilowatt heat pump installed at New Belgium’s Fort Collins brewery. The appliance sends the AtmosZero team, about 30 people in all, a steady stream of data.

New Belgium, the famed maker of Fat Tire Ale, is using the steam to boil wort, a sugary liquid, with bitter hops to create the libation’s flavor and aroma profile before it’s fermented into beer. When running at full capacity, AtmosZero’s heat pump is able to provide about 30% to 40% of the brewery’s steam needs.

The AtmosZero team has been carefully monitoring the New Belgium installation’s performance since June, and they’ve been able to apply lessons from the pilot project to improve their product, Bandhauer said.

While AtmosZero’s first heat-pump unit was stuffed with equipment, the latest version is roomier. The streamlined model has fewer parts, reducing costs and making it easier to service, Bandhauer said. The team is also finessing the design of its crucial compressor wheels.

Michaela Eagan, a spokesperson for New Belgium, said the brewer is focused on evaluating how the heat pump performs and hasn’t committed to any future orders.

But AtmosZero is in talks with dozens of other potential customers and is anticipating demand through 2027, Stark said. Currently, the startup’s plant contains one crane-assisted heat-pump assembly bay; that’ll grow to four. Whereas the first Boiler 2.0 took roughly three months to build, AtmosZero could be cranking out 120 to 240 heat pumps per year by 2030, he estimated.

So far, the company has primarily targeted factories for its product. But AtmosZero is also branching out into steam for other big buildings. In September, New York awarded the startup $500,000 through the Empire Technology Prize to install two of its heat pumps at the Midtown Hilton hotel in Manhattan, a project that’s still in negotiation, Stark said.

After touring the factory floor, we sat down in a nearby taproom. I asked Stark how he felt about what he and his cofounder Bandhauer were building. “Neither of us were wanting to be founders,” Stark said. “It’s a hard thing to reinvent the boiler.”

Yet “it’s rare to find an opportunity to have such a positive impact [on carbon emissions] and be profitable,” he added. “Todd and I and our whole company see that opportunity.”

A clarification was made on Oct. 16, 2025: This story has been updated to clarify that the money AtmosZero received to install heat pumps at the Midtown Hilton is through the Empire Technology Prize, a combination of private-sector and state funding.

States are ramping up efforts to get residents to switch from fossil-fuel-fired heating systems to all-electric heat pumps. Now, they’ve got a big new tool kit to pull from.

Last week, the interagency nonprofit Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management, or NESCAUM, released an 80-page action plan laying out key strategies to turbocharge heat-pump deployment. Individual states are already putting many of these tactics to the test.

California, Colorado, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, and the District of Columbia together committed to ambitious heat-pump adoption goals last year. Washington state joined the pact last week. Their targets: By 2030, heat pumps will make up 65% of the sales of residential heating, air conditioning, and water heating equipment. By 2040, that percentage is to climb to 90%.

The goals are essential for addressing climate change. Buildings are directly responsible for 13% of U.S. carbon emissions, in part due to the fossil fuels burned on-site to heat indoor air and water. All-electric heat pumps can do those jobs running on clean power.

The NESCAUM action plan comes as the Trump administration clings tenaciously to fossil fuels. In recent months, the federal government has rolled back energy-efficiency standards for appliances, imposed chaotic tariffs that are raising costs for consumers, and put an early expiration date on the $2,000 federal tax credit that helps homeowners afford heat pumps.

Despite these headwinds, the report shows that “states are still finding creative ways to move forward,” said Emily Levin, policy and program director for NESCAUM.

HVAC heat pumps are routinely two to four times as efficient as gas furnaces, capable of heating and cooling interiors using the same physics that refrigerators employ to chill your cucumbers. Heat-pump water heaters work the same way and are three to five times as efficient as gas water heaters. By eschewing fossil fuels, these technologies improve air quality and typically save people money over the long term, even if, on average, they cost significantly more up-front than conventional heating systems. (At least one startup, though, is trying to change that.)

Heat pumps are slowly catching on. In the U.S., the units outsold gas furnaces by their biggest-ever margin last year, but their share of the market is still modest. Citing data from the Air-Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute, a trade association, Levin said that in 2021, heat pumps accounted for about 25% of the combined shipments of gas furnaces, heat pumps, and air conditioners, the three largest reported HVAC categories. In 2024, they’d risen to about 32%.

“No matter how you look at it, there are still a lot of gas furnaces being sold, there are still a lot of one-way central air-conditioners being sold — all of which could really become heat pumps,” Levin said.

Produced in consultation with state agencies, environmental justice organizations, and technical and policy experts, the NESCAUM report lays out a diverse set of more than 50 strategies — both carrots and sticks — covering equity and workforce investments, obligations to reduce carbon, building standards, and utility regulation. A wide range of decision-makers, often in collaboration, can pull these levers — from utility regulators to governor’s offices, state legislatures, and energy, environment, labor, and economic development agencies. Here are six recommendations from the report that stand out.

NESCAUM’s Levin stressed that the report is “a menu — not a recipe.” Each state will need to consider its own goals and constraints to pick the approaches that fit it best, she added.

Still, “I see [heat-pump electricity] rates as one of the areas that’s most promising,” Levin said. Massachusetts’ reforms “are really going to change their customer economics to make it more attractive to switch to a heat pump.”

When done right, rate design also avoids the need for states to find new funding. “You’re not raising costs on anybody, you’re only reducing costs,” Levin said. At a time when households are seeing energy prices rise faster than inflation, the tactic could have widespread political appeal, she noted.

NESCAUM plans to check back in with states and report out on their progress each year, Levin said. “The cool thing about our work is that we bring states together to learn from one another,” she added. “Part of making this transition happen more rapidly is lifting up the things that are really working well.”

Heat pumps can save households money. But the super-efficient, electric HVAC appliances are almost always more expensive to install up-front than gas- or oil-fired options.

Jetson, a Vancouver-based heat-pump startup, thinks it can change that — with a combination of new software, hardware, and a direct-to-consumer approach.

“We are typically anywhere from 30% to 50% below competitive quotes,” said cofounder and CEO Stephen Lake.

The company’s name, which may resonate with certain cartoon-watchers, harkens back to an era when people believed that “technology would enable this exciting, better future for us all,” Lake said.

His roughly 75-person startup, which Lake would only divulge has “raised a bit of money,” launched sales last October to try and deliver on that promise. So far, it’s installed heat pumps — which can both warm and cool spaces — in nearly 1,000 homes in Colorado, Massachusetts, and British Columbia, Canada, and it plans to expand into New York in a few weeks, he said.

Today, Jetson is announcing a move it says will further cut costs: It’s rolling out its very own heat pump, the Jetson Air. The startup has partnered with an undisclosed manufacturer to make the appliance.

Whole-home ducted heat pump projects in the areas where the startup currently operates typically have a price tag of $25,000 to $30,000, Lake said, citing data from bids that customers routinely share with Jetson. Those prices are also about the norm nationwide, according to electrification nonprofit Rewiring America — and are significantly higher than the cost of a new gas furnace ($8,000 to $10,000) plus air conditioner ($3,000 to $5,000), Lake said.

Jetson says its average heat-pump installation cost is way less than the national average: just $15,000.

Many markets also offer thousands of dollars in heat-pump rebates, which the startup deducts from what customers pay out of pocket. In these spots, Jetson can offer heat pumps in some cases for as little as $5,000, Lake said. At that point, it’s a financial no-brainer to choose the electric equipment over a gas furnace.

Bringing down the up-front costs of heat pump adoption is crucial, especially in the U.S., where the federal government is pulling back incentives for the HVAC tech. More than 80 million homes across the U.S. and Canada burn fossil fuels for heat, according to government data. These furnaces and boilers rack up around 3 to 6 metric tons of carbon emissions per household annually, Lake said, and heat pumps are the way to cut that pollution. Swapping a fossil-fueled heater out for a heat pump slashes CO2 about as much as trading in a gas car for an EV.

Jetson is taking a fresh approach to deliver its low heat-pump prices: vertical integration.

Traditionally, equipment manufacturers sell heat pumps to brands, which sell them to distributors, who sell them to HVAC installers, who sell them, finally, to homeowners, Lake explained.

“At each stage, there’s a markup,” said Brett Webster, a principal on RMI’s carbon-free buildings team. “There’s good reason to think that a vertically integrated company could reduce costs.”

Jetson cuts out the middlemen. It buys the heat pumps, stores them in its own warehouses, and has its own in-house installers ride out in the company’s electric vans to put the appliances in homes, Lake said.

Using custom software, Jetson also cuts costs by scoping heat pump projects virtually rather than sending someone out to each would-be customer. Last year, Jetson acquired whole-home decarbonization startup Helio Home and built upon its thermal modeling software that can accurately size heat pump systems remotely. In most cases, the first time an installer comes to an abode is to put in the heat pump. The company additionally uses proprietary software to process rebates.

Jetson’s tech-forward approach flows from Lake’s background. The Canadian entrepreneur previously built a smart-glasses startup called North that Google acquired for an undisclosed amount in 2020. With the climate crisis pressing and heat pumps an undersung solution, Lake and some of his colleagues from North pivoted to HVAC, he said.

Others are also developing software to improve the heat-pump customer experience. Manufacturing startup Quilt uses over-the-air updates to improve its minisplit heat pumps over time. And home-electrification startups, such as Zero Homes, have created software to reduce the cost of heat pump projects.

In the view of RMI’s Webster, Jetson’s vertically integrated approach is “taking the next step.”

Jetson installed a heat pump for Matt Machado, who works as an expert on surface water and groundwater rights at Colorado law firm Lyons Gaddis, for a cost of about $7,000 — a third of what the eight or nine other contractors he got bids from offered. He’ll get another $2,000 off when he claims the federal Energy-Efficient Home Improvement Credit (25C) at tax time. Jetson “made it easy,” Machado told Canary Media. On pricing, “they’re very transparent.”

Jetson’s low cost was thanks in part to the company’s up-front application of state and local rebates, which tallied roughly $6,000, Machado said. Other contractors didn’t make these reductions, which would’ve left him to absorb the cost and file for the rebates on his own.

With the launch of its heat pump, Jetson aims to provide a product that delivers the customer experience of a Tesla or Rivian electric vehicle, Lake said.

The Jetson Air heat pump is “comparable to the best models,” rated to work down to minus 22 degrees Fahrenheit, he added. Brands such as Bosch, Carrier, Lennox, and Mitsubishi already make popular options for cold-climate markets.

What sets Jetson’s appliance apart, Lake said, are its built-in software, sensors, and controls. Homeowners can use these features to schedule their heat pumps to run at times of the day when the grid isn’t strained and power is cheaper. The tech also lets Jetson monitor a system’s performance and reach out if something needs to be fixed.

“What are the amperages being drawn? Is your air filter getting dirty? Are there any error codes coming up? Is anything not running 100%? We can tell all that remotely,” he said. No other heat pump on the market today is capable of that, he noted.

Ultimately, Lake said that these improvements in functionality compound into more savings for the customer.

HVAC “is this very unsexy category, which I love,” Lake said. “So many things we’re doing — applying software to make [products] more efficient and designing better systems — [are] improvements that in other industries have happened a long time ago.” But they’re “completely novel in this HVAC world.”