LOVELAND, Colo. — For a moment, I held in my hand the cool heart of a heat pump.

I was standing inside the cavernous facility where the startup AtmosZero is building its novel steam-producing heat pumps. The all-electric technology is meant to replace the gas-burning boilers that factories rely on to make everything from Cheez Whiz to notepaper to beer. I visited the 83,000-square-foot plant on a sunny September morning to learn how AtmosZero is working to make industrial heat — but without the planet-warming carbon emissions.

The grapefruit-sized component I grasped, called a compressor wheel, helps to produce the heat that’s needed to make steam with AtmosZero’s tech, Todd Bandhauer, the startup’s chief technology officer and cofounder, explained from the factory floor.

AtmosZero opened the facility, once a mothballed Hewlett-Packard electronics plant, earlier this year to begin commercial production of its Boiler 2.0, a machine the size of a shipping container that can be hoisted by crane and plunked inside another factory.

The company has big ambitions for its electrified solution. In the United States, around 40% of the fossil fuels that factories consume is burned in boilers to make steam for processes including sterilizing equipment, breaking down wood chips for papermaking, and cooking, curing, pasteurizing, and drying food.

“Steam is the most important working fluid, both in industry and the built environment,” said Addison Stark, the startup’s CEO and cofounder. “The boiler is what drove the Industrial Revolution.”

AtmosZero spun out of Bandhauer’s research at Colorado State University in 2021, and it has since raised nearly $30 million from investors and $3.2 million from the Department of Energy to realize its steam-heat dreams. In June, the startup finished installing a 650-kilowatt pilot unit at the New Belgium brewery in Fort Collins, Colorado. At the Loveland facility, the company is working to build and deliver its first commercial heat pumps by around 2026.

The factory floor was quiet when I visited last month, with custom-made parts in open boxes or on pallets awaiting assembly. But Stark said he sees the facility getting much busier as the company works to fill demand from potential buyers, who face increasing pressure from state regulators and their own customers to slash gas-related pollution.

“I want to see electrification [across] industry and actually get ourselves on track to get to the emissions reductions that we all want to see in this century,” Stark said. In his view, “The only path to that is steam decarbonization.”

Industrial heat accounts for about 13% of U.S. energy-related carbon emissions. Much of that comes from burning fossil fuels in boilers to produce steam, though a small fraction of factories have adopted electric-resistance boilers instead. These machines can at most be 100% efficient, meaning that all the energy that goes into the boiler comes out as heat.

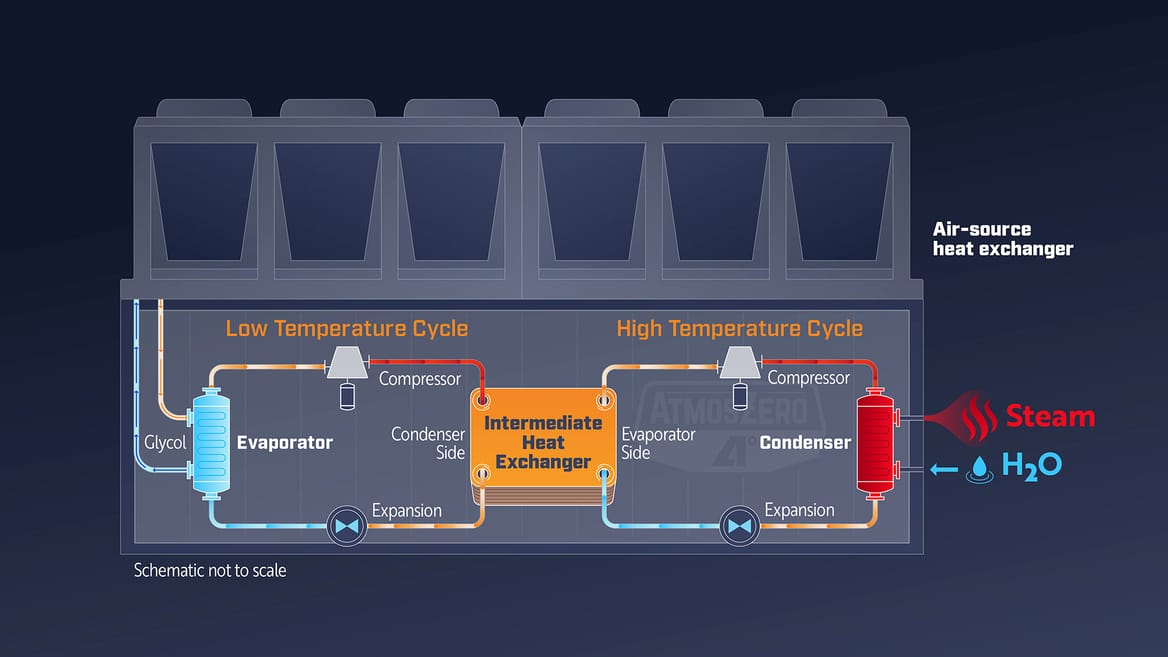

Heat pumps, by contrast, move heat instead of making it. The appliances use electricity and a refrigerant to gather thermal energy from someplace else — say, the open air or a water pipe — and concentrate it using a compressor to deliver the heat where it’s needed. This process can be 300% to 400% efficient or higher.

AtmosZero and a handful of other manufacturers are developing new heat pumps that will allow the technology to replace an even larger share of gas-fired boilers in factories.

Existing heat-pump models can churn out heat up to about 160 degrees Celsius (320 degrees Fahrenheit) — hot enough to cover roughly 44% of industrial process-heat energy, according to a 2022 report by nonprofit American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, or ACEEE. New designs are expected to reach up to 200˚C (392˚F), addressing about 55% of factory heat needs.

“Being able to meet more than [half of] of industrial heat demand with a single technology is really impactful,” said Ruth Checknoff, senior project and research director at the Renewable Thermal Collaborative, a coalition of organizations working to decarbonize process heat and buildings.

At the AtmosZero factory, Bandhauer broke down how the Boiler 2.0 delivers more than hot air.

The compressor wheel I held had precisely sculpted blades that swept out in a tight spiral. When secured in the heat pump, a motor spins the wheel at up to 30,000 rotations per minute, throwing heat-carrying vapor against the equipment’s chamber walls. That increases the pressure, making the vapor hotter. AtmosZero’s heat pump utilizes two of these compression cycles, a kind of one-two punch, to ramp up the temperature enough to boil water.

Then, voila: You have steam as hot as 165˚C (329˚F).

Still, for all the apparent benefits, industrial heat pumps on the market today have struggled to gain widespread adoption. To start, they’re more expensive to install than gas boilers, which can last for decades — limiting the business case for replacing them. In the United States, fossil gas has historically been cheap enough in many places that a boiler has cost less to run than a heat pump, even though the latter uses a fraction of the energy.

States like California, Colorado, Illinois, New York, and Pennsylvania are adopting policies to help address these hurdles. That includes incentives for manufacturers to invest in tech that slashes emissions, air-quality regulations that limit pollution from their operations, and cheap financing for capital-intensive decarbonization projects. Advocates are also pushing states and utilities to work together to set more favorable electricity rates for factories.

Despite the technology’s high price tag, heat pumps can deliver significant savings on factory owners’ utility bills, according to ACEEE. A heat pump’s payback time — the amount it takes to recoup savings equal to the added installation cost — can be just a handful of years.

“We should invest time and energy into making sure that we have the right policies and enabling conditions to deploy [heat pumps] at scale,” Checknoff said.

AtmosZero isn’t the only company making steam-producing heat pumps. Other manufacturers — including GEA, Karman Industries, Heaten, Piller Blowers and Compressors, and Skyven Technologies — are proving out the tech, and some are starting to install their own machines in factories in the U.S. and Europe.

These systems often supplement existing fossil-fueled boilers by capturing a plant’s excess heat that would otherwise be wasted. That approach helps maximize a heat pump’s efficiency: Since the waste heat is already toasty, it’s easier for the tech to turn that into even higher-temperature heat for making steam.

Customers often want to actively harness this throwaway warmth to keep electric bills as low as possible, Checknoff said. But because every facility is different, installing a heat pump to slurp up that thermal energy can be costly and cumbersome.

AtmosZero is aiming for economies of scale, similar to how solar panels and home heat pumps are mass-manufactured and deployed in a modular way. “We want to bring that to the steam boiler,” Stark said during my visit.

The startup’s heat pump can be installed in a day, requiring only hookups to electricity and water lines and the factory’s control system. It’s as simple as replacing an old gas boiler with a new one, he said. And at New Belgium’s brewery, putting in the pilot heat pump this spring didn’t disrupt operations.

“They were able to continue to brew beer,” Bandhauer added.

AtmosZero’s product does have a key trade-off: It’s not as efficient as heat pumps that competitors install to harness waste heat. Those systems produce more heat with the same amount of energy. That ability is measured with what’s called the coefficient of performance, or COP. Whereas other companies’ installations might render a COP of seven or more, AtmosZero’s heat pump has a COP of up to roughly two.

But the Boiler 2.0 is cheaper to install, costing about one-tenth to one-fifth the expense of integrating a waste-heat system, Stark said. He estimated that the savings on the installation costs should enable AtmosZero’s projects to pencil out financially in five years or less.

At his desk inside the AtmosZero factory, a young engineer named Mason Mollenhauer pulled up on his computer screen a rendering of the 650-kilowatt heat pump installed at New Belgium’s Fort Collins brewery. The appliance sends the AtmosZero team, about 30 people in all, a steady stream of data.

New Belgium, the famed maker of Fat Tire Ale, is using the steam to boil wort, a sugary liquid, with bitter hops to create the libation’s flavor and aroma profile before it’s fermented into beer. When running at full capacity, AtmosZero’s heat pump is able to provide about 30% to 40% of the brewery’s steam needs.

The AtmosZero team has been carefully monitoring the New Belgium installation’s performance since June, and they’ve been able to apply lessons from the pilot project to improve their product, Bandhauer said.

While AtmosZero’s first heat-pump unit was stuffed with equipment, the latest version is roomier. The streamlined model has fewer parts, reducing costs and making it easier to service, Bandhauer said. The team is also finessing the design of its crucial compressor wheels.

Michaela Eagan, a spokesperson for New Belgium, said the brewer is focused on evaluating how the heat pump performs and hasn’t committed to any future orders.

But AtmosZero is in talks with dozens of other potential customers and is anticipating demand through 2027, Stark said. Currently, the startup’s plant contains one crane-assisted heat-pump assembly bay; that’ll grow to four. Whereas the first Boiler 2.0 took roughly three months to build, AtmosZero could be cranking out 120 to 240 heat pumps per year by 2030, he estimated.

So far, the company has primarily targeted factories for its product. But AtmosZero is also branching out into steam for other big buildings. In September, New York awarded the startup $500,000 through the Empire Technology Prize to install two of its heat pumps at the Midtown Hilton hotel in Manhattan, a project that’s still in negotiation, Stark said.

After touring the factory floor, we sat down in a nearby taproom. I asked Stark how he felt about what he and his cofounder Bandhauer were building. “Neither of us were wanting to be founders,” Stark said. “It’s a hard thing to reinvent the boiler.”

Yet “it’s rare to find an opportunity to have such a positive impact [on carbon emissions] and be profitable,” he added. “Todd and I and our whole company see that opportunity.”

A clarification was made on Oct. 16, 2025: This story has been updated to clarify that the money AtmosZero received to install heat pumps at the Midtown Hilton is through the Empire Technology Prize, a combination of private-sector and state funding.