In some parts of California, the lead state on electric vehicles, utilities are facing a challenge that will eventually spread nationwide: Local grids are struggling to keep up with the electricity demand as more and more drivers switch to EVs.

The go-to solution for this type of problem among most utilities is to undertake expensive upgrades, paid for by all their customers, so that the grid can accommodate the new load.

But there’s a cheaper option: Utilities could simply make sure that the EVs that plug into their grids aren’t all charging at the same time.

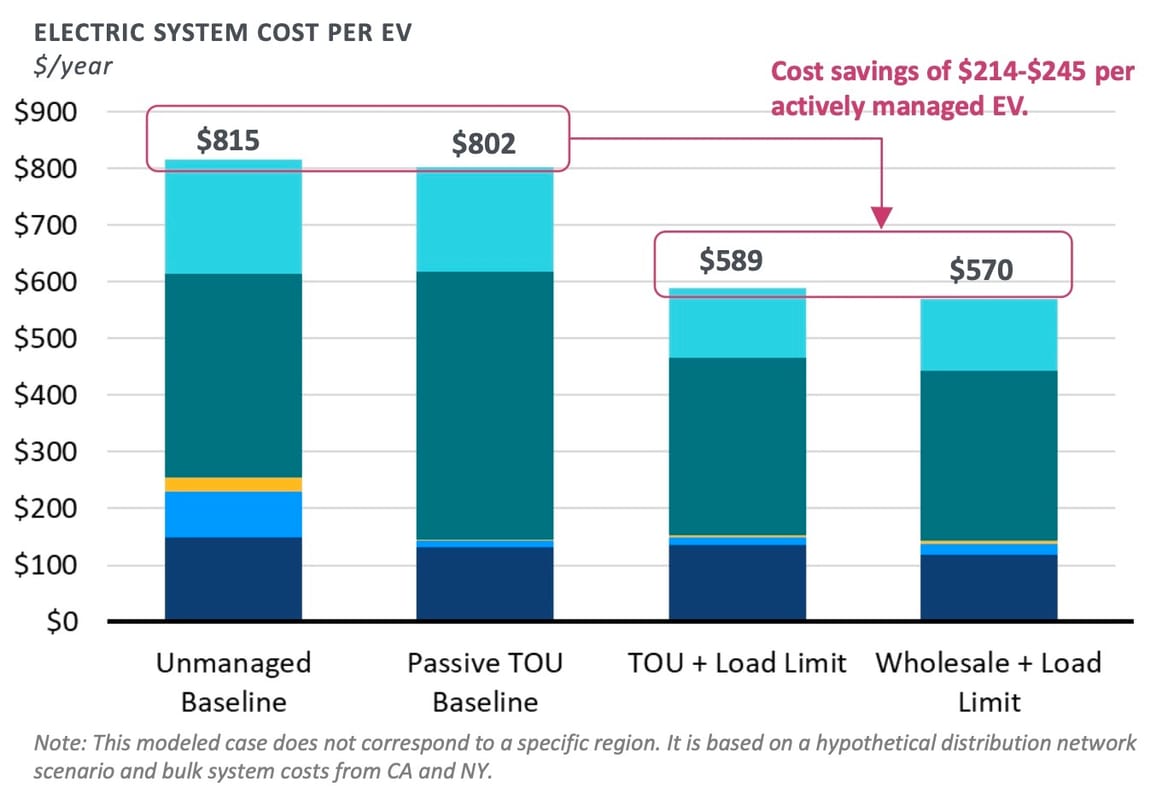

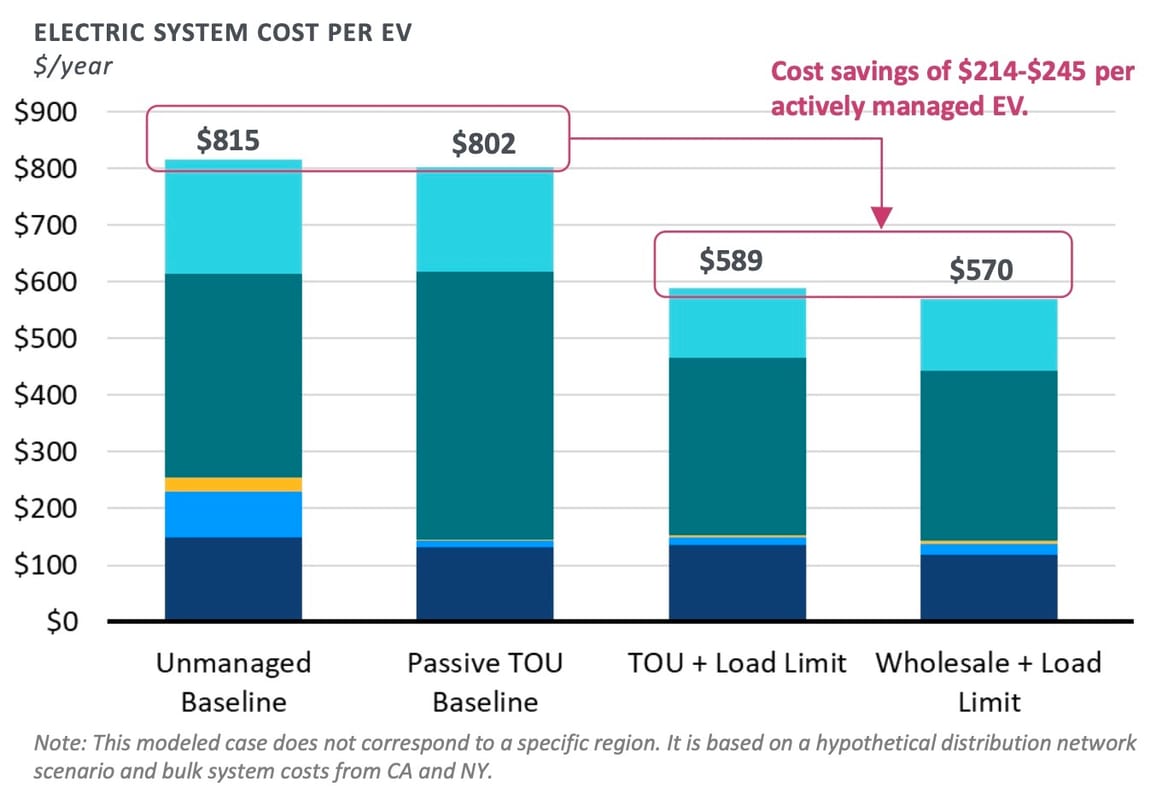

So finds a new report prepared by The Brattle Group, an energy consultancy, on behalf of EnergyHub, a company that operates virtual power plants (VPPs) for more than 170 utilities. In an analysis of 58 EV owners in Washington state, the authors found big cost benefits from “active managed charging,” the process of modulating when and how much EVs charge to minimize their impact on the grid.

It’s a crucial finding, as researchers say the approach is most effective when deployed before lots of EVs show up on utilities’ grids. Previous research has found that the cost of unmanaged charging could add as much as $2,500 per utility customer once EVs reach higher levels of penetration on utility grids. In California, that cost is already impacting utilities’ plans. Other fast-growing EV regions, including New York and Massachusetts, could soon face similar challenges.

Managed charging is a simple concept but not a simple task. To make it work, utilities have to get EV owners to enroll in managed charging programs, which requires convincing them that they won’t be left with a depleted battery when they need to drive somewhere.

Utilities also need to persuade their regulators — and their own internal grid planners — that these charging regimes are reliably relieving the local transformers, feeder lines, and substations that would otherwise be overloaded by too many EVs charging at once. If utilities can’t do that, they’ll wind up having to build new grid infrastructure anyway.

Managed charging isn’t a new idea. Utilities across the country are starting to test such programs operated by EnergyHub, Camus Energy, ev.energy, Kaluza, WeaveGrid, and other companies.

And the benefits of scaling up such programs could be major, said Akhilesh Ramakrishnan, managing energy associate at The Brattle Group. “With active managed charging, you can roughly double the capacity of the grid to host EVs,” he said.

That would help utilities contain the high and rising costs of maintaining and expanding their distribution grids, which now make up the biggest share of rapidly rising U.S. utility rates.

To achieve the savings that this approach promises, “it’s really important that the solution is implemented without damaging customers’ reliance on their cars,” Ramakrishnan said — in other words, making sure “that their cars are charged by when they need them.”

That’s where more sophisticated managed charging comes in, said Freddie Hall, a data scientist at EnergyHub. The company runs managed EV charging pilots for utilities such as Arizona Public Service and Southern Maryland Electric Cooperative, and applied similar techniques to the EV drivers in Washington state analyzed for the new report.

EnergyHub takes pains to forestall the risk of leaving EV owners without the charge they need by the time they need it, Hall said. For example, “we’ve found that some people don’t constantly update their charge-by time settings,” he said, referring to the deadline that each driver sets to have a full battery. So EnergyHub uses drivers’ past charging behaviors to forecast when they typically unplug and to make sure they’re scheduled to be fully charged by that time.

Occasionally, that requires allowing EVs to collectively pull more power from the grid than permitted under the “load limits” that utilities have set for the transformers, distribution feeders, and substations delivering it, he noted. To deal with that, EnergyHub dispatches charging in ways that minimize those overloads: “We spread out that charging to achieve a lower peak over a longer duration.”

EnergyHub’s managed charging doesn’t just limit impacts on the distribution grid, Hall said, but also co-optimizes for when power is cheaper across the grid at large. It targets times when wholesale electricity prices are low — although it will choose to forego that cheaper energy if using it would violate its local load-limit settings.

These techniques require a lot of information, making them harder to implement than time-of-use rates — the most common way that utilities try to limit EV charging loads today.

Those programs typically charge more for power at times when the grid at large is under peak demand stress, usually during late afternoons or early evenings in the summer or early mornings in the winter, and they charge less for power during off-peak times, typically late at night.

But these time-of-use rates can actually cause more grid stress than they resolve, Ramakrishnan said. That’s because they create a secondary “snapback effect” when rates change from expensive to cheap, and everyone’s EV starts charging at once.

“We’re not trying to say that time-of-use is a bad solution in general, or doesn’t work at all,” Ramakrishnan said. “At lower penetrations, there’s value in shifting EV load to move away from the time that other loads peak. But fairly quickly — when you get to 7% to 10% penetration — EVs themselves start to set the peak.”

That’s one reason why the report recommends that utilities start working on active managed charging programs before EV purchases start to overwhelm the grid. The other reason is to match the pace of how utilities plan ahead for grid investments, Hall said.

“I worked at two utilities before coming to EnergyHub. Grid planning is a multiyear-type deal,” he said. “Getting infrastructure for the distribution grid takes up to 18 or more months. Solutions like these help utilities put off some decisions for up to 10 years, if not more.”

The ability to push out grid upgrades is particularly valuable at a time when power demands are growing even as utilities are under pressure to contain costs, Ramakrishnan said. “A lot of utilities are capital constrained right now.”

At the same time, EVs represent a massive opportunity for utilities to increase electricity sales — and that could put downward pressure on the rates that all customers have to pay. That’s because regulators set those rates based on how much money utilities need to earn to cover their costs. More sales divided by fewer costs means lower rates over the long run.

At the very least, managed charging can better align EVs’ costs with their benefits, Ramakrishnan said. “One, you push the upgrade out and can save money for longer,” he said. “Two, the upgrade gets pushed out to when there are more EVs — that means there are more EVs paying for it.”

This commentary represents the research and views of the authors. It does not necessarily represent the views of the Center on Global Energy Policy. The piece may be subject to further revision. This commentary was funded through a gift from G. Leonard Baker, Jr. More information is available at Our Partners.

As the United States and Europe navigate a difficult and uneven shift toward full battery electric vehicles (BEVs), the US and EU auto markets are under heavy pressure, lagging China’s market in terms of supply chain and battery technology readiness. In the US, the Trump administration is rolling back Biden-era electric vehicle (EV) policies, and its newly imposed tariffs may increase BEV prices, potentially slowing the pace of transition to BEVs. In this context, US and EU policymakers and automakers are reassessing where plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs) fit within their industrial and climate strategies. The idea is that, given the US’s and EU’s less-developed minerals and battery sectors, range anxiety, and slowly developing charging infrastructure, PHEVs—with their smaller batteries relative to BEVs—can serve as a bridge technology that still offers carbon-reduction benefits.

This theory appears intuitive, but whether it maps with the projected global competitiveness and relevance of PHEVs remains an open question. This commentary analyzes current market and technology trends to better understand the future of PHEVs in an increasingly electrified transportation market. These trends indicate that PHEVs are unlikely to serve as a durable path for the US and Europe to achieve global EV competitiveness. Instead, their value lies primarily in serving as a transitional complement within domestic markets, provided policymakers address real-world emissions gaps, cost barriers, and supply-chain vulnerabilities that extend from China’s dominance. In other words, PHEVs can play a role in specific market segments and extend the utilization of the industrial base and therefore jobs in the short-term, but they can’t do so beyond this since both BEV and PHEV competitiveness is built on battery competitiveness now concentrated with Chinese players.

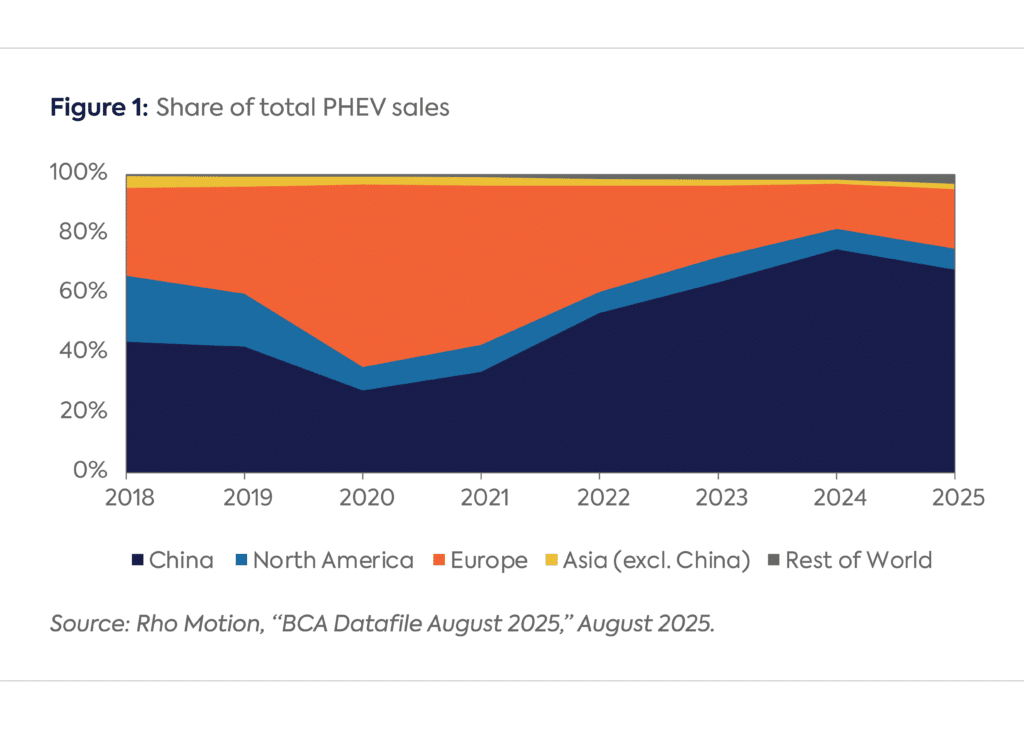

Global EV sales reveal an evolving dynamic between BEVs and PHEVs. In the early years of market growth, up to 2018, PHEVs were a popular entry point for consumers transitioning away from internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs), representing about 40 percent of total EV sales. As technology advanced and battery prices fell, BEVs surged to nearly 70 percent of total EV sales between 2018 and 2024, supported by policy incentives and growing consumer confidence in charging infrastructure.[i] Since 2024, PHEVs have grown only modestly, accounting for roughly one-third of global sales versus two-thirds for BEVs through mid-2025.[ii] In 2024, there were around two BEV models for every PHEV model available in China, Europe, and the United States. Globally, the ratio was over three to one.[iii]

Much of this dynamic has been shaped by China, which has looked at transport electrification as a way to compensate for its competitive disadvantage in ICE markets. Chinese demand today accounts for 67 percent of global PHEV sales and 56 percent of BEV sales.[iv] This is largely explained by China’s early investments in battery manufacturing and supply chains, which cemented its global leadership in EVs. China currently maintains the broadest support for PHEVs of any country in the world through a combination of incentives, including a 10 percent vehicle purchase tax exemption to production-side credits.[v] Europe, whose PHEV market is mostly geared towards high profit margin premium models, represents around 20 percent of global PHEV market share.[vi] The US follows in third place, at around 7 percent, with the few supportive federal policies that had been in place being rolled back over the past year, though PHEV support persists via California’s Zero-emission Vehicle Regulation.[vii]

PHEVs have also benefited from broader technological advancements in the EV industry, which is building next-generation batteries with higher energy densities and longer ranges. The size of PHEV battery packs has increased from an average of 13 kilowatt hour (kWh) in 2018 to 23 kWh by 2025, and thus allowed for longer electric-powered ranges.[viii] However, because PHEVs must accommodate both a battery pack and an ICE, they require two parallel and therefore complex propulsion systems that make their average price per kWh higher than that of BEVs, by roughly three times in 2024.[ix] In 2024, affordable PHEV options were limited in Europe and the United States, with only one model priced below $40,000 in Europe and four in the United States, while China stood out with nearly 40 models under $25,000.[x] Conversely, in China, PHEV prices have consistently dropped as a result of the country’s competitiveness in batteries: the sales-weighted average for medium-sized PHEVs in 2024 was 10 percent lower than conventional models in the same category, causing PHEV sales in the sector to more than double.

A key appeal of PHEVs lies in their ability to handle longer trips even when charging infrastructure is insufficient or congested. In China, this advantage has been reinforced by steady improvements in range: between 2020 and 2025, the electric-only range of PHEVs grew by more than 20 percent, reaching nearly 100 kilometers. By contrast, ranges in Europe and the United States have plateaued at around 65 kilometers.[xi]

Another distinct advantage of PHEVs is their lower mineral intensity. In 2025, European BEVs had an average pack size of about 70 kWh, compared with 19 kWh for PHEVs, in the passenger and light duty vehicle segment. In the US, it was 94 kWh compared with 19 kWh.[xii] US and European BEV and PHEV batteries also include a heavy makeup of nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM) battery cells, which use more and more expensive critical minerals compared with LFP batteries. This means that, all else being equal, European and US PHEVs use three to four times less critical minerals than BEVs. In a context of critical mineral supply constraints and chokepoints,[xiii] they may therefore enable more drivers to shift to electric cars more quickly, with a spillover effect on demand for supporting infrastructure, particularly charging infrastructure. This can certainly be a boost to electrifying the transport sector, if drivers primarily use their batteries (see below). But a broader shift to PHEVs does not necessarily mean global competitiveness (see below also).

As with BEVs, China leads the global PHEV market, bolstered by favorable policy, consumer enthusiasm for Range-Extended Electric Vehicles (REEVs), and ongoing government incentive programs.[xiv] Chinese PHEV sales are expected to reach around 8 million units by 2030 in the base scenario and 9.3 million units in the upside case, compared with 1.6 to 1.7 million in Europe and 1.2 to 1.4 million in the US.[xv] While this suggests growth potential for Western markets, it also reflects China’s enduring grip on PHEV markets and models.

China’s dominance in the sector raises the question of whether a strategic refocus on PHEVs could allow Western automakers to compete globally, rather than solely within domestic markets. Given that PHEV competitiveness is tightly linked to battery manufacturing capabilities, countries applying tariffs to shield domestic BEV and battery industries may find themselves at a disadvantage in exporting PHEVs. Under such conditions, PHEVs could support national transition goals but are unlikely to generate new global leaders in transport electrification.

Domestic appetite remains notable, however. In the US, BEVs and PHEVs accounted for 8 percent and 2 percent of new passenger car sales in 2024, respectively—and these shares are expected to grow to 26 percent and 17 percent by 2034.[xvi] This suggests PHEVs will continue to have a role in the transition, even as global markets favor full electrification. Despite the expiration of federal incentives in the US in 2025, analysts still project steady, albeit slower, growth in broader EV uptake, suggesting that consumer interest is proving more stable than policy.[xvii] Still, in a global context, the trend is toward full battery electrification, with PHEVs increasingly acting as a transitional technology whose relevance narrows as infrastructure, costs, and regulations evolve in favor of BEVs. In China, 2024 BEV and PHEV sales stood at 26 percent and 19 percent, respectively, with PHEVs expected to peak near 30 percent in 2032 before declining to 18 percent by 2040 as BEVs reach 80 percent. Europe follows a similar path: BEV and PHEV shares were 14 percent and 6 percent in 2024, and projected to reach 67 percent and 8 percent by 2034, consistent with Europe’s policy focus on full electrification.[xviii] In 2025, PHEV sales climbed by almost 60 percent year on year, which analysts say reflects temporary policy and registration effects rather than a structural shift away from BEVs.[xix]

Battery demand further illustrates the growing divide between BEVs and PHEVs. In 2024, BEVs accounted for 148 gigawatt hours (GWh) of battery demand in Europe and 112 GWh in the United States, compared with just 17 GWh and 6 GWh from PHEVs. The battery share in the US for PHEVs was mostly NCM chemistries, comprising more than 99 percent of battery share in 2025.[xx] This contrasts with China, where lithium-ion phosphate (LFP) technology—used in 61 percent of PHEV batteries and projected to reach 76 percent by 2030[xxi]—has driven down costs and reinforced China’s structural advantage in PHEV battery pricing. These lower costs cascade into final vehicle prices, further strengthening China’s competitiveness.

Automakers and suppliers are increasingly pressing for PHEVs to be recognized as part of Europe’s decarbonization pathway. The German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA) has recommended maintaining PHEVs beyond 2035 and easing regulatory adjustments, arguing that hybrids can help preserve industrial capacity and employment across the automotive value chain.[xxii] Similarly, the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) and the European Association of Automotive Suppliers (CLEPA) have stressed a technology-neutral approach, noting that high electricity prices, trade tariffs, and uneven charging infrastructure require flexibility in compliance pathways.[xxiii]

This lobbying reflects not only industrial and job-protection motives—the European automotive sector employs over 13 million people[xxiv] and PHEV manufacturing may preserve existing supplier ecosystems—but also changing market dynamics: forecasted PHEV sales are rising for most years, and imports from China surged from 31,000 in 2024 to 46,000 in the first half of 2025, largely driven by BYD and Chery New Energy, which are taking advantage of PHEVs not being included in the EU’s additional duties.[xxv]

Market projections show that the absolute number of PHEVs sold will indeed increase in the medium-term (albeit slower than BEVs). The purpose of this increase, however, is not dictated by the data but instead will be determined by policy. PHEVs can function either as a detour that slows full electrification or as a limited but useful boost to electric driving, lower mineral demand, and scaling domestic battery and charging ecosystems. Different actors hold different preferences: some automakers see PHEVs as a way to preserve existing supply chains and employment, while regulators focused on long-term decarbonization increasingly worry about real-world emissions and lock-in risks. If the strategic goal is full electrification—an assumption that cannot be made for the US under the Trump administration—then the following challenges will need to be addressed for PHEVs to make a meaningful contribution.

PHEV pricing shows no consistent pattern across global markets, reflecting differing policy priorities and manufacturer strategies. While the general expectation is that PHEVs will cost less than BEVs due to their smaller batteries, they have become increasingly expensive relative to ICEVs—by over 30 percent for midsize cars and 50 percent for SUVs since 2022—partly because fixed battery system costs are spread over fewer cells and their pack designs are complex and as such add costs.[xxvi] In Europe, PHEVs remain the most expensive option across all vehicle categories, with only one of roughly 130 models priced below $40,000, compared with more than 40 BEVs and 155 ICEVs under the same threshold.[xxvii] In the United States, prices vary by segment: PHEVs are cheaper than BEVs in some SUV categories but considerably more expensive in others. In China, PHEV prices fell in 2024 while those in Germany rose, reflecting the influence of larger battery packs and domestic supply chain dynamics.[xxviii] The result is a fragmented pricing landscape in which PHEVs occupy multiple strategic roles—premium compliance vehicles in some markets, affordable entry-level hybrids in others—creating uncertainty for both automakers and consumers about the long-term position of these vehicles in the electrification transition.

REEVs—a type of PHEV that uses an ICE to recharge the battery when depleted—previously emerged as a way to appease consumer range anxiety concerns, illustrating both the flexibility and uncertainty facing the electrification of transport. In China, REEVs doubled their market share in 2024 from 5 percent to 12 percent before BEVs gained ground.[xxix] This temporary surge was viewed as evidence of REEVs’ potential as a transition technology when supported by strong policy incentives—such as China’s vehicle trade-in schemes—and appealing OEM offerings from manufacturers like Li Auto and BYD. Outside China, however, REEVs remain niche, with only 2,515 registrations in the first half of 2025, [xxx] though the United Kingdom and a few European markets have seen some uptake. Automaker strategies reflect these divergent signals: while groups like Volkswagen and Stellantis have reaffirmed their commitment to fully electric production, others continue to see hybrid and range-extended technologies as useful bridge options, particularly in regions where charging networks remain uneven. Yet it is unclear whether broader REEV adoption would meaningfully accelerate electrification or lower emissions, as these vehicles still rely on combustion engines for part of their range and may replicate some of the behavioral challenges observed with PHEVs.

PHEVs are often promoted as a lower-emission alternative to ICEVs, but real-world data has shown that they can emit nearly five times the official stated emissions and about the same as ICEVs, mostly due to usage patterns and the amount of time users are running on electricity versus fuel combustion. The mismatch between expected and actual emissions has accelerated efforts—mostly in Europe—to phase out PHEV subsidies, with the UK going as far as banning PHEV and hybrid EV sales by 2040.[xxxi] Remaining incentives are now conditional (based on electric range or corporate fleet use) and are being phased out in favor of zero-emission BEVs.[xxxii] As governments tighten climate targets, many automakers are accelerating their transition towards fully electric vehicles over hybrids. In the EU, stricter fleet-wide CO2 emission limits are pushing manufacturers to increase BEV sales to avoid financial penalties. This regulatory shift may gradually become hostile to PHEVs, particularly as questions continue to surface in Europe about their real-word emission performance.[xxxiii] For PHEVs to play a bigger part in transport decarbonization pathways in Europe and beyond, this element is a key area to address. Indeed, countries outside of Europe that are working on reducing their carbon footprint in transport may favor BEVs if they lack evidence that PHEVs have contributed to emissions reduction in advanced economies like the US and EU.

The United States and Europe still face a narrow window in which PHEVs can play a constructive role in marrying automaker competitiveness with decarbonization by sustaining consumer engagement in electrification, supporting segments where charging access remains uneven, and preserving parts of the existing automotive supply base during a difficult transition. Yet these benefits do not alter the structural reality that China’s dominance in PHEV-relevant supply chains (particularly LFP and low-cost pack integration) limits the extent to which hybrids can meaningfully strengthen Western global competitiveness in an increasingly electrified market. In global markets, the long-term signals are clear: BEVs continue to gain ground as infrastructure expands, costs fall, and regulatory frameworks tighten around real-world emissions.

If PHEVs are to function as complements rather than detours, policy design will be decisive. The US and EU Governments could take the following steps:

Together, these measures can allow PHEVs to serve the narrow but highly useful purpose of supporting the electrification transition by easing short-term market pressures while keeping long-term industrial competitiveness at the center of policy.

Victoria Prado is a Research Associate at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, where she integrates the Trade and Clean Energy Transition initiative and conducts research on the geopolitics of critical minerals in Latin America. She was the first hire at a successful climate startup in Brazil, where she supported investor rounds, led the business intelligence team, and gained hands-on experience with carbon markets in emerging economies. Victoria also worked at the Rockefeller Foundation, advancing projects to expand energy access, accelerate coal phase-out in Southeast Asia, and deploy clean energy storage solutions in sub-Saharan Africa. Her work lies at the intersection of climate policy, sustainable development, and global energy systems, with a regional focus on Latin America. She holds a Master of Science in Sustainability Management from Columbia University and has experience in advising major players in Brazil’s oil, gas, and mining sectors on long-term sustainability strategy.

Dr. Tom Moerenhout is a Professor at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and leads the Critical Materials Initiative at Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy. His work extends to roles as Senior Advisor at the World Bank Energy and Extractives Group, Executive Director at the Geneva Platform for Resilient Value Chains, and Senior Associate at the International Institute for Sustainable Development and Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals and Metals. He has served as Visiting Professor at NYU, Sciences Po Paris, and the Geneva Graduate Institute.

Tom specializes in the intersection of geopolitics and industrial policy, particularly as they relate to energy, critical minerals, and battery supply chains. His work focuses on integrating the interests and influence of multiple actors across complex political economies to improve supply chain security and resilience. Tom has published extensively on sustainable development and energy policy reforms, specifically on energy subsidies, critical materials, and the economic development of resource-rich countries.

He has advised and consulted for various stakeholders, including the White House, Departments of Energy and State, USTR, and policymakers in several other countries, including the EU, Canada, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, DRC, Egypt, Iraq, Chile, and Brazil. His collaborative efforts span organizations such as the OECD, IEA, World Bank, UNCTAD, UNEP, OPEC, IRENA, and several philanthropic foundations.

Tom holds two master’s degrees and obtained his PhD at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva. This academic background includes fellowships at LSE and the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. He was also a Fulbright and Albert Gallatin Fellow, and a Swiss National Science Foundation Scholar.

In his downtime, Tom enjoys reading & writing, culinary experiences, football, skiing, and chess.

[i] Rho Motion, “BCA Datafile August 2025,” August 2025; International Energy Agency (IEA), “Global EV Outlook 2025,” May 14, 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025.

[ii] Rho Motion, “BCA Datafile August 2025,” August 2025.

[iii] IEA, “Global EV Outlook 2025,” May 14, 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025.

[iv] Rho Motion, “BCA Datafile August 2025”, August 2025.

[v] IEA, “Global EV Outlook 2025,” May 14, 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025.

[vi] Ibid.; Rho Motion, “BCA Datafile August 2025”, August, 2025.

[vii] Rho Motion, “BCA Datafile August 2025,” August 2025; California Air Resources Board, “Zero-Emission Vehicle Regulation,” n.d., https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/zero-emission-vehicle-program.

[viii] Rho Motion, “BCA Datafile August 2025,” August 2025.

[ix] IEA, “Global EV Outlook 2025,” May 14, 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Rho Motion, “EV & Battery Quarterly Outlook Q1 2025,” 2025.

[xiii] IEA, “Global EV Outlook 2024: Trends in Electric Vehicle Batteries,” April 23, 2024, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024/trends-in-electric-vehicle-batteries.

[xiv] Rho Motion, “EV & Battery Quarterly Outlook Q1 2025,” 2025.

[xv] Rho Motion, “EV And Battery Forecast: August 2025,” August 2025. This commentary draws on Rho Motion’s EV & Battery Forecast (Q2 2025) for regional projections of BEV and PHEV sales, battery demand, and technology trends. Rho Motion is an intelligence firm specializing in EV and battery markets whose granular, model-level forecasting is widely used by industry and policymakers. As with all proprietary market intelligence forecasters, not all of its underlying assumptions and methods are publicly disclosed, and long-term projections involve inherent uncertainty, particularly in markets without a clear policy direction, like the United States.

[xvi] Rho Motion, “EV And Battery Forecast: August 2025,”August 2025.

[xvii] Bloomberg, “Electric Vehicles Make Up 11 Percent of US Car Sales,” October 16, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-10-16/1-in-10-us-car-sales-is-electric-but-future-is-uncertain-without-subsidies.

[xviii] Rho Motion, “EV And Battery Forecast: August 2025,” August 2025.

[xix] Rho Motion, “Record Monthly EV Sales, Breaking the Two Million Mark,” October 15, 2024, https://rhomotion.com/membership-industry-updates/record-monthly-ev-sales-breaking-the-two-million-mark/.

[xx] Rho Motion, “EV And Battery Forecast: August 2025,” August 2025.

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] VDA, “10-Point Plan for Climate-Neutral Mobility: Reduce CO2 Emissions in Transport, Ensure the Competitiveness of the Automotive Industry,” June 5, 2025, https://www.vda.de/en/press/press-releases/2025/250606_PM_2030-2035_CO2-Flottenregulierung_EN.

[xxiii] ACEA, CLEPA, “The EU Risks Missing the Turn on Its Automotive Transition – September’s Strategic Dialogue Is the Change to Correct Course,” August 27, 2025, https://www.acea.auto/files/Joint-ACEA-CLEPA-letter-to-President-von-der-Leyen.pdf.

[xxiv] European Commission, “President von der Leyen Chairs Third Strategic Dialogue with the European Automotive Industry on 12 September,” September 10, 2025, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_2038.

[xxv] EV And Battery Forecast: August 2025,” August 2025; Benchmark, “Chinese EV Brands Look to PHEVs to Avoid EU Tariffs,” May 2, 2025, https://source.benchmarkminerals.com/article/chinese-ev-brands-look-to-phevs-to-avoid-eu-tariffs; Rho Motion, “EV & Battery Quarterly Outlook Q1 2025,” 2025.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] IEA, “Global EV Outlook 2025,” May 2025, https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025.

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] Rho Motion, “EV And Battery Forecast: August 2025,” August 2025; Rho Motion, “EV & Battery Quarterly Outlook Q1 2025,” 2025.

[xxx] T&E, “Smoke Screen: The Growing PHEV Emissions Scandal,” October 16, 2025, https://www.transportenvironment.org/articles/smoke-screen-the-growing-phev-emissions-scandal.

[xxxi] Rho Motion, “EV & Battery Quarterly Outlook Q1 2025,” 2025.

[xxxii] European Commission, “European Alternative Fuels Observatory: Portugal,” n.d., https://alternative-fuels-observatory.ec.europa.eu/transport-mode/road/portugal/incentives-legislations.

[xxxiii] Rho Motion, “EV & Battery Quarterly Outlook Q1 2025,” 2025.

Ford, a century after it launched the modern automotive era, has given up on its early ambitions to charge into the electrified future.

The company announced that it will delete nearly $20 billion in book value to extricate itself from its EV investments, an eye-popping loss that amounts to one of the biggest corporate impairments ever.

The company, of course, views it differently: The move is a “decisive redeployment of capital,” it said on Monday, as it rolled out a string of related strategic changes alongside the write-down.

The pivot hits particularly hard in the southeastern Battery Belt, where Ford had invested in multibillion-dollar BlueOval plants to produce batteries and electric vehicles. The EV battery facility in Glendale, Kentucky, will lay off about 1,600 employees, and local outlet the Memphis Commercial Appeal reported that a Ford factory in Tennessee will hire around 1,000 fewer workers than previously planned, now that it is making gas trucks instead of electric ones.

As Ford retreats from EVs, though, it’s enthusiastically embracing battery-making — announcing plans to repurpose the Kentucky plant to fuel its entrance into the grid storage market. It expects to spend roughly $2 billion over the next two years to launch production of lithium iron phosphate cells and package them into 20-foot containers that hold at least 5 megawatt-hours of storage capacity, equivalent to a Tesla Megapack. The plan is to ship at least 20 gigawatt-hours annually by the end of 2027.

“This strategic initiative will leverage currently underutilized electric vehicle battery capacity to create a new, diversified and profitable revenue stream for Ford,” the company said in a statement. Ford also plans to make cells for home battery units at its factory in Marshall, Michigan.

Ford recently cut a deal with partner SK On, the South Korean battery maker, to dissolve their joint venture. Ford will keep the Kentucky battery plant while SK On takes the one at the sprawling BlueOval City complex near Memphis, Tennessee. That means batteries will still be made in that factory, just not exclusively for Ford products.

“They have built up battery manufacturing capacity, and now they need to do something with it,” said Pavel Molchanov, managing director for renewable energy and clean technology at financial services firm Raymond James. “While EV demand is languishing, U.S. energy storage deployments are skyrocketing.”

Ford’s sunny rhetoric about a “customer-driven shift” can’t hide the sheer enormity of the blow to its overall business.

As of Sept. 30, Ford’s accountants pegged its corporate value at more than $47 billion. Now Ford must lower that by $19.5 billion to reflect the dissolution of the joint venture agreement with SK On and the loss of planned EV models. The company will have to spend money to end production of the all-electric F-150 Lightning, switch to producing a gas-and-battery-powered extended-range model, and retool factories for new, non-EV production.

The move comes as EVs account for just about 10% of new vehicle sales in the U.S., far below the global figure of 25%. Though EV sales reach new records each year, the rate of growth has slowed, and there’s little reason to expect momentum to improve given recent federal policy changes.

“U.S. EV sales have never lived up to expectations,” said Molchanov. “That was true even while the tax credit was in place. Now, there’s no more tax credit, and EV sales have fallen off a proverbial cliff.”

The consumer EV tax credit ended in September as a result of the Republican budget law, taking away an incentive that helped lower or eliminate the premium for buying electric compared to a similar gas-powered model. Now, too, the average price of regular gasoline has dipped below $3 a gallon for the first time in four years, while residential electricity prices rose 13% over the first three-quarters of this year, much faster than inflation.

“In terms of commodity prices, this is the worst of both worlds for EVs,” Molchanov said.

Ford’s announcement says a lot about the changing fortunes of EVs and energy storage in the U.S. right now.

It used to be that EVs were on the exponential growth curve, and stationary storage offered a modest side hustle for any leftover batteries. Now, between American automakers’ apparent inability to make affordable models and the Trump administration’s slashing and burning of federal EV incentives, that market is heading for some doldrums.

Grid battery providers, by contrast, are seeing business surge. Revenue from Tesla’s energy division, home to the Powerwall home battery and Megapack for large-scale storage, grew 67% last year compared to 2023, and broke $10 billion for the first time, even as the company’s market-leading EV business lost revenue.

Overall, the U.S. will install a record amount of battery capacity on the grid this year. Though analysts predict some dropoff over the next couple of years as the industry adapts to new federal anti-China rules, the utility-scale outlook through 2030 has actually increased 15% since the first half of this year, according to industry group American Clean Power.

Demand from AI data centers plays a massive role in that: Hyperscalers are realizing that strategically placed batteries can unlock capacity at critical constrained hours, in some cases letting the companies build computing hubs years earlier than they could if they waited for conventional grid upgrades. Ford, not coincidentally, will target data centers with its new battery products.

The grid storage market has to date depended almost entirely on lithium iron phosphate cells made in China. But when President Donald Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act this summer, he preserved federal tax incentives for energy storage deployment while adding a new bureaucratic regime to make projects prove they don’t source parts from China in excess of newly set limits.

Starting in 2026, that will push storage developers to source U.S.-made batteries. There aren’t a lot of options today: LG, after making EV batteries in Michigan for years, began producing lithium iron phosphate cells there for grid use earlier this year. Tesla, Fluence, and others are following suit — in fact, the U.S. is on track for self-sufficiency in cell production for grid storage use by the end of 2026, according to the Energy Storage Coalition.

If project developers end up in a race to secure scarce domestic supply come 2027 or 2028, Ford could find eager buyers in spite of its short track record.

Still, that’s no guarantee of success. Other companies have been building grid storage products for years, working out kinks, packing more capabilities into a tighter footprint, and building relationships with savvy customers. Ford has a reputation for reliability in pickup trucks, not in grid batteries.

Put another way, Ford is copying Tesla’s strategy of leveraging EV prowess to sell grid storage, but doing so a decade later and without the EV prowess to lean on.

In the waning days of the Biden administration, the Metropolitan Mayors Caucus announced an award of $14.5 million in federal funds to build almost 200 EV charging stations across the Chicago area.

A few weeks later, after President Donald Trump had taken office, the funds were “gone,” as the caucus’ environmental initiatives director, Edith Makra, put it. One of Trump’s earliest actions was to suspend the Charging and Fueling Infrastructure grant program, which is where the money for the Chicago-area charging effort had come from.

The Metropolitan Mayors Caucus is forging ahead with its EV Readiness program anyway. Even without the funds, there’s much it can do to help Chicago-area towns and cities get more chargers in the ground and EVs on the road. In fact, the caucus has already been doing that work for the last three years, thanks to funding from the Illinois utility ComEd.

Leaders say it’s an example of how local programs can make progress even when federal dollars are ripped away. It’s also a way to help meet Illinois’ ambitious goal of placing 1 million EVs on the state’s roads by 2030, a major leap from the roughly 160,000 registered as of November.

This fall, the caucus launched its fourth EV Readiness cohort, wherein representatives of 16 municipalities will learn how to upgrade their permitting and zoning processes related to EV charging, raise awareness about EVs and state and local incentives, and craft mandates for charging access.

Since 2022, 38 communities have gone through the program, and state data shows that EV registrations in most of these communities have increased faster than in the state as a whole.

Cost is one of the core factors holding back EV adoption in Illinois, and beyond.

Trump administration policies have made that hurdle even higher. Under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, rebates of $7,500 for new EVs and $4,000 for used ones expired in September, while the federal tax credit for EV chargers will disappear in June 2026.

But price is not the only factor, and as manufacturers manage to bring down costs, these other barriers will become even more crucial to address.

For example, many people hesitate to buy an electric vehicle because of range anxiety — the fear they will run out of battery and be unable to find a reliable charger. Or they may feel intimidated by the concept of an EV in general. That’s where the EV Readiness program comes in, helping municipalities increase charging stations and educate residents on EVs and the incentives that are still available.

Participating communities can achieve bronze, silver, or gold status by taking certain actions on a checklist of over 130 possible steps. These include nuanced zoning and permitting changes, like examining when chargers can be in the public right of way and processing permit applications for the equipment in 10 days or less.

Streamlining such regulations helps charging-station companies that want to do business in the area, and the owners of gas stations, apartment buildings, parking garages, corporations, and other locations who want to install ports.

Makra called EV-friendly zoning and permitting codes “a glide path for sensible development.”

“Municipalities have a big role to play in making charging infrastructure available to their communities,” added Cristina Botero, senior manager of beneficial electrification for ComEd, which funds the EV Readiness program as part of a state mandate called beneficial electrification. “This program is so effective because it’s helping the leadership of these communities understand what steps need to happen.”

The EV Readiness program also encourages municipalities to establish requirements for charging access in new construction and to train first responders to deal with EV battery fires. Participants can take steps to boost public awareness, too, informing residents about utility rate programs conducive to EV charging and creating a landing page about EVs on the town website.

“People sometimes think that the dollars are the only reason people are not transitioning to EVs,” said Botero. “But a big part of it is education.”

The EV Readiness program has so far attracted a wide range of municipalities, from the EV-friendly and relatively high-income Highland Park to smaller communities that otherwise “do not stand out from a sustainability or transportation standpoint,” noted Makra.

“What’s so gratifying is to see the diversity in jurisdictions,” she said. “They’re stepping forward and saying, ‘This would be good for our community.’”

That diversity is reflected in the new cohort, too, which includes the wealthy Chicago suburb of Winnetka and the small farm town of Sandwich.

Glen Cole, assistant manager for the city of Rolling Meadows, said the EV Readiness program helps local governments make it easier for building owners and businesses to comply with state law, which requires that all parking spaces at new large multifamily buildings and at least one space at new smaller residences have the electrical infrastructure needed to one day install an EV charger.

Rolling Meadows is a leafy suburb of about 24,000 people. Along with Chicago, it became one of three municipalities to earn gold status in the cohort that finished this summer.

Before that designation, Rolling Meadows already hosted a number of EV chargers on-site at corporate employers, including aerospace firm Northrop Grumman and the Gallagher insurance company’s global headquarters. Seven chargers are also under construction at Rolling Meadows’ city hall. The city adopted an ordinance in February mandating that new or renovated gas stations have one EV fast-charger for every four fuel pumps, and that parking lots with 30 or more spots have EV chargers.

Cole said the EV Readiness program helped advance the city’s progress

“The biggest part for us was putting in one place all these standards and expectations for an installer or investor or business, and incrementally easing into policy requirements to provide charging at public locations,” Cole said. “The availability of quick, easy, high-quality access to charging is a big determinant of whether people will take the leap to EVs, and it’s something the city can exercise a lot of control over.”

Multiple items on the EV Readiness checklist require collaborating with ComEd and making the public aware of the utility’s EV incentives and billing plans conducive to charging.

ComEd, whose northern Illinois territory is home to 90% of the state’s EVs, offers rebates for households that install “smart” Level 2 EV chargers and covers the cost of any electrical work needed. In 2026, the maximum rebate will be $2,500, and could change with market conditions, according to the utility. ComEd also covers the cost of fast chargers and the “make-ready” construction and prep work for businesses and public agencies, and offers rebates for EV fleet vehicles.

The utility has paid out over $130 million for more than 8,700 charging ports and more than 2,700 fleet vehicles since early 2024, with 80% of the funds spent in communities identified as low-income or equity-eligible, per state law prioritizing investment in underserved communities. Low-income and equity-eligible customers receive higher rebates, and Botero said the utility has done extensive outreach in those areas, where the tax-credit expiration will make it especially hard for people to afford EVs.

“The opportunities we offer are more important than ever,” Botero said.

Botero said that after the Trump administration ended EV tax credits, the utility “went back to the drawing board” and increased the rebates it had previously planned for 2026, though some of the amounts will still be lower than in 2025. Incentives for light-duty vehicles in non-equity areas will end, but the utility will increase rebates for some types of vehicles in equity areas. For example, the 2026 rebate for electric school buses in those areas will be $220,000 to $240,000, up from $180,000 this year.

The state of Illinois offers $4,000 rebates for low-income EV buyers and a $2,000 rebate for those who don’t qualify as low-income. The state also this month started accepting applications for about $20 million in grants for public charging stations. In the third quarter of 2025, Illinois logged a record number of EV sales, mirroring national trends as people scrambled to buy EVs before the tax credits expired in September.

Despite the troubling federal outlook, Botero said, “the silver lining is Illinois is extremely committed to EVs.”

This story was first published by Grist.

Phillip Stafford has been converted. After two years of driving a Tesla, he says there’s no going back to gasoline — the money he saves on fuel alone makes that clear. And since his work as a crisis counselor takes him all over Richmond, Virginia, he charges often.

That’s made him picky about where he buys electrons. On a crisp fall afternoon last month, Stafford had his Model 3 plugged in at a Sheetz. A red-and-white Wawa sandwich wrapper on the seat hinted at where his heart lies in that convenience-store rivalry. Still, brand loyalty goes only so far when the battery is running low. Given a choice between the two, Sheetz wins. “It has more watts, so it charges a little faster,” he said.

The seemingly small question of where to spend 20 or so minutes topping off a battery reveals the transformation taking hold among fuel retailers. For more than 50 years, chains like Wawa, Sheetz, and Love’s Travel Stops have defined when and where people refuel. As EVs reshape mobility, these retailers are among those embracing charging.

Their challenge goes beyond providing power to turning the time that drivers spend plugged in into profitable foot traffic. Selling electricity alone won’t pay the bills; the real money lies in selling snacks. Making that work requires reimagining what a pit stop looks and feels like, even as costly infrastructure upgrades and shifting federal policies complicate the transition.

Wawa and Sheetz are two of the furthest along. The Pennsylvania-based companies have built out hundreds of chargers and enjoy fervent fanbases that make them two of the most popular convenience stores in the country. Their made-to-order sandwiches, vast array of snacks, and clean restrooms have made them regular stops for road trippers and commuters alike — and now, for EV drivers looking to recharge their cars and, often, themselves.

They offer a glimpse of the road ahead. As electric vehicles move ever further from niche toward norm, the focus for retailers like these could shift from which one offers the cheapest fuel to which one can make waiting for the car to fill up the best experience.

“The problem with a lot of current gas stations is [they’re] not that nice of a place to spend 15, 20, or 30 minutes,” said Scott Hardman of the Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, Davis. “Hopefully in the future, we’ll see more of them turn into coffee shops, cafes — places you actually want to be.”

That future is slowly coming into focus. Retailers like Wawa and Sheetz have spent the past few years exploring what the transition from selling gasoline to selling electricity might look like. Even with the headwinds EVs face, at least 26 percent of cars on U.S. roads could be electric by 2035, and some projections suggest they could account for 65 percent of all sales by 2050.

The two chains offer a place to plug in at over 10 percent of their locations. Wawa has installed more than 210 chargers, while Sheetz provides more than 650 at 95 locations that have logged at least 2 million sessions. Clean amenities and expansive menus with offerings like Wawa’s turkey-stuffed Gobbler and Sheetz’s deep-fried Big Mozz have placed them near the top of convenience store satisfaction rankings.

Both say embracing cars with cords builds on what already attracts customers. Wawa frames it as an extension of its “one-stop” model for food and fuel. Its competitor calls charging “a seamless extension of the Sheetz experience.” The language differs, but the message is the same: Selling electricity works if it brings people like John Baiano inside.

The New York resident owns two Tesla Model Ys and travels throughout the northeast for his two businesses — a Bitcoin consultancy and a horse racing operation. He plugs in at Wawa because the stores are clean, offer plenty of amenities, and provide a comfortable place to check in with clients. “I use the bathroom, maybe get a snack,” he said. (He prefers the turkey pinwheel.) “I was a little nervous about the charging aspect of things. Once I started experiencing this, it was seamless.”

At the moment, most public quick chargers are tucked away in the far corners of shopping centers, inside parking garages, and other functional but hardly inviting places to spend 20 minutes. They’re fine when you’re out and about running errands, but not terribly appealing at night and not particularly conducive to a road trip.

Tesla dominates the space with its Supercharger network, which provides over half the country’s quick chargers, with Electrify America, EVgo, and ChargePoint together accounting for another 25 to 30 percent. Retailers like Love’s Travel Stops, Pilot Flying J, and Buc-ee’s are joining Sheetz and Wawa in working with those networks and others to add chargers alongside gas pumps. Their efforts signal how a system built for gasoline is starting to evolve for electricity.

Everything Stafford and Baiano like about plugging in at a convenience store reflects an Electric Vehicle Council study that ranked security, lighting, and 24/7 access as the three things drivers want most in a charging station. Another survey found that 80 percent of them will go out of their way to get it. Reliability is another concern — and a frequent complaint with the nation’s current charging infrastructure. As EVs become more common, drivers are going to be less willing to put up with malfunctioning or broken chargers than the early adopters were.

Ryan McKinnon of the Charge Ahead Partnership, which pushes for a comprehensive charging network, sees fuel retailers as a logical place to build out such a system because they already have the right locations and amenities. “What EV charging needs is a competitive and lucrative marketplace where folks can actually make money selling EV charging,” he said.

Therein lies the challenge. Buying and installing a quick charger can cost more than $100,000. Beyond that lie fluctuating prices from utility companies, which one leading charging provider said is a key factor in deciding where to locate the devices. Retailers won’t recover that by selling electrons alone, given that the machines might generate just $10,000 in revenue each year, Hardman said. EVgo noted in its second-quarter earnings report that it earned just under $12,000 per stall.

Making this work for retailers requires getting people out of their cars and into the stores. Just as gas retailers earn two-thirds of their profit selling sandwiches, snacks, and sodas, those selling electricity can expect to do the same. Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that installing an EV charger increased spending by 1 percent, which would cover 11 percent of the cost of installing the charger. (Other studies have found similar benefits for surrounding businesses; Tesla Superchargers can boost revenue by 4 percent.)

For some retailers, chargers are a loss leader meant to pull customers into stores, said Karl Doenges of the National Association of Convenience Stores. Others see them as a way to secure increasingly scarce electrical capacity while it’s available. Some are moving “forward on a charging station, even though they don’t think [the market is] 100 percent ready,” he said.

Even the strongest business cases for installing the devices depended on Washington’s help to pencil out. Incentives that the Biden administration created through the Inflation Reduction Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law provided billions in grants, tax credits, and matching funds to help expand the fueling infrastructure of tomorrow, particularly in rural and low-income communities that a free market might overlook.

When Donald Trump won the 2024 presidential election, there was little doubt federal support for this ambitious effort would change. Yet the upheaval was more dramatic than expected. In February, the Trump administration paused the $5 billion National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure, or NEVI, program, the backbone of Washington’s effort to build a nationwide charging network. Fuel retailers, which have been some of the effort’s biggest beneficiaries, expressed concern.

The administration reluctantly reinstated NEVI, which had installed just 126 charging ports by the time Trump won his second term, in August. “If Congress is requiring the federal government to support charging stations, let’s cut the waste and do it right,” Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy said at the time. But with most of the funding allocated, the program will likely expire in 2026.

When it revived NEVI, the Trump administration updated recommendations for states, which administer the funds, in a way that seems to favor a national network run by big chains with highway operations. The Federal Highway Administration’s guidance explicitly recommended building charging infrastructure near fuel retailers.

Nonetheless, at least some of those companies see this as a difficult moment for EV charging. Joe Sheetz, executive vice chairman of the family-owned company, has said momentum is slowing because much of the funding has come from the government and big players like Tesla. Some smaller chains are backing away, but Sheetz said his company will keep at it.

Even as EV adoption grows, most people will continue to plug in largely at home. About 80 percent of charging occurs there, and some providers, like It’s Electric, are skipping partnerships with fuel retailers, focusing instead on slower and cheaper level 2 chargers that are convenient for apartments or homes without garages and do the job in four to 10 hours.

Charles Gerena, a lead organizer of the advocacy organization Drive Electric RVA, rarely visits a public charger in his Chevy Bolt. But on longer trips, he’s noticed more opportunities to plug in, especially in rural areas where fast charging was once scarce. On a recent road trip to Virginia Beach in his wife’s Ford Mustang Mach-E, he took advantage of the car’s ability to tap the Tesla Supercharger network and used the app PlugShare to find a reliable station — at a Wawa.

“I like Wawa’s food better than Sheetz,” he said. “I think I’m in the minority. My daughter actually likes Sheetz better.” Still, for Gerena, reliability trumps loyalty. “If it gets a lousy rating, I’d be wary of going to it, regardless of which gas station it was.”

Despite customer loyalty that can sometimes divide households, retailers are learning that sandwiches and snacks aren’t enough. Success will depend on providing plenty of opportunities to plug in, and making sure the hardware works when drivers need it.

Gas cars are sputtering, stuck in the slow lane — and battery-powered vehicles are gaining on them fast.

A massive shift has occurred in less than a decade. At their all-time high, in 2017, global sales of pure internal combustion vehicles hit 79.9 million units, per data from the International Energy Agency. Last year, 54.8 million internal combustion cars were sold, a 31% reduction.

Meanwhile, electric vehicles are ascendant. Nearly 11 million new EVs were sold worldwide in 2024, the vast majority in China, while consumers also bought 6.5 million plug-in hybrids — the ones with both gas engines and rechargeable batteries. Those figures represent enormous growth from just a few years ago. Back in 2017 when gas cars were at their peak, a measly 800,000 EVs and 400,000 plug-in hybrids were sold worldwide.

EVs are already more popular than fossil-fuel-guzzling vehicles in several places. And I’m not just talking about Norway. In China, the world’s largest EV manufacturer and auto sales market, around 60% of new cars sold this year will be electric. By 2030, the IEA expects that number to hit 80%.

Still, for the foreseeable future, the number of EVs on the road will pale in comparison to the number of gas-powered cars. (Older gas cars will likely be puttering around for a while even as EVs beat them out in sales.)

And the way forward is not necessarily smooth. In some countries, including the United States, the upfront costs of many EV models remain too high for consumers. Drivers are also still wary about charging infrastructure and range, even as chargers become more common. Plus, the Trump administration has eliminated U.S. policies encouraging EV adoption, causing analysts to revise down estimates of sales for what is one of the world’s largest auto markets.

But despite these speed bumps, the trend lines are tough to ignore. We’re well past peak internal combustion vehicles, and battery-powered cars are experiencing exponential growth. Eventually, that adds up to a world dominated by EVs, rather than by gas engines.

Back in May of 2021, Ford’s F-150 Lightning debuted with star-spangled flair. Then-President Joe Biden visited Ford’s sparkling new Rouge Electric Vehicle Center in Michigan, where the company displayed the truck in front of a giant American flag alongside its gas-powered siblings. And after declaring that “the future of the auto industry is electric,” Biden even took the Lightning for a zippy test drive.

The picture is decidedly less bright today. A factory fire has forced Ford to pause production of the groundbreaking truck — and The Wall Street Journal reports that the company is considering halting production of the Lightning altogether after years of sluggish sales.

It’s not just the Lightning that has stalled. Electric trucks as a category have sputtered, largely due to their cost. A standard gas-powered F-150 starts at just shy of $40,000, while a Lightning with the lowest trim package starts at $55,000. Charging at home can help EV drivers recoup that cost difference, but it’s hard to ignore the initial sticker shock — especially given that federal EV incentives are now dead under President Donald Trump’s July budget law.

Politics may also be to blame. While the gas-powered Ford F-150 is among the most popular vehicles in counties that voted for Trump in 2020, the president’s repeated railing against EVs, coupled with Biden’s early endorsement, has put electric cars at the center of America’s polarized politics.

Still, even the Cybertruck, which carries a very different political connotation, isn’t doing so hot. Tesla sold just under 40,000 Cybertrucks last year in the U.S., while Ford sold about 33,500 Lightnings.

Consumers simply seem a lot more interested in electric sedans and SUVs than electric trucks. Even with sales supercharged as consumers raced to tap expiring EV tax credits, Americans purchased just about 60,000 electric pickup trucks through the third quarter of this year, but bought more than 900,000 electric SUVs, sedans, and sports cars.

But there might be a path forward for the electric truck yet, says Art Wheaton, an expert on transportation industries at Cornell University: small and cheap.

“Changing policies, lower demand, and higher costs have made electric trucks a harder sell,” he said. “Canceling the Lightning and replacing with a much lower-cost, smaller electric truck makes long-term sense given the current policies towards electric vehicles.”

A tale of two gas bans

Massachusetts and New York may be neighbors, but they’re seemingly heading in different directions when it comes to transitioning their buildings off of fossil fuels.

Back in 2022, Massachusetts created a pilot program that let 10 municipalities prohibit fossil-fuel hookups in new buildings and major renovations. Advocates tell Canary Media’s Sarah Shemkus that the program is already lowering energy bills and reducing emissions — and lawmakers are considering new legislation to bring another 10 cities and towns into the fold.

New York has also made big commitments to clean up its buildings, including enacting rules this summer that would require all-electric appliances in most new construction. But last week, 19 Democratic state lawmakers sent a letter to Democratic Gov. Kathy Hochul urging her to postpone implementation of the All-Electric Buildings Act. And on Wednesday, the state agreed, pausing the rules from taking effect at the end of this year.

COP30 kicks off with a focus on climate resilience

Leaders and advocates from around the world gathered in Brazil this week for the beginning of the United Nations’ COP30 climate summit. The Trump administration didn’t send a formal delegation, but that was OK with many diplomats — and with California’s Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom, who called the president a “wrecking ball” to climate action during one panel.

Digs at the U.S. were aplenty during the first days of the conference, as were discussions of the need to ramp up climate adaptation and resilience work as extreme weather events grow more frequent and more intense. Jamaica, for example, is facing as much as $7 billion in damages — a third of its gross domestic product — after last month’s Hurricane Melissa. But in the storm’s aftermath, Jamaica has also shown how resilience efforts pay off. The island has deployed more than 60 megawatts of rooftop solar power since 2015, and many solar-equipped homes became neighborhood hubs in the wake of Melissa’s destruction.

Fighting for climate funds: Clean-energy groups and the city of St. Paul, Minnesota, sue the Trump administration over $7.5 billion in cuts to climate-related projects in Democratic-led states. (New York Times)

Stretching coal shutdowns: The Trump administration is poised to order two Colorado coal power plants to stay open past their planned retirements this year, even as the costs of keeping a Michigan coal facility open skyrocket. (Canary Media)

Pacific petrol: The Trump administration considers opening California coastal waters to offshore oil drilling for the first time in four decades, drawing pushback from advocates and Gov. Newsom. (Washington Post)

More supply, more demand: The International Energy Agency says the world is on track to build more renewable-energy projects in the next five years than it has over the last 40 — but rising demand means the world will keep relying on fossil fuels, particularly gas, for years to come. (The Guardian, Associated Press)

Pipeline “betrayal”: New York and New Jersey issue the state-level approvals needed for a previously rejected natural-gas pipeline to move forward, leaving environmental advocates feeling “betrayed” but still determined to fight the project. (Inside Climate News)

Government restart: President Trump signs a funding bill that will reopen the government, sending furloughed federal employees back to work. (E&E News)

RGGI retreat: Pennsylvania’s Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro signs a budget bill that includes a provision to leave the Northeast’s Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a cap-and-invest program. (Inside Climate News)

Electric vehicle sales just hit an all-time high in the U.S. — but don’t expect the boom to last long.

For every 10 cars that automakers sold from July through September, one was an EV, according to fresh data from Cox Automotive. In other words, nearly 440,000 new battery-powered vehicles hit the nation’s roads during the third quarter of 2025. The previous single-quarter record, set in the final three months of last year, isn’t even in the same ballpark.

But the sales surge has a catch. Buyers flocked to EVs last quarter because it was their final opportunity to take advantage of a $7,500 federal tax credit that disappeared at the end of September under President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act. The incentive was previously slated to last until 2033.

Under these conditions, “the all-time sales and share records in Q3 were all but certain,” Cox wrote in a blog post accompanying the data. This quarter, by contrast, the company expects EV sales to “drop notably.”

Still, the U.S. electric vehicle market isn’t dead in the water without the tax credit. Already, automakers that have invested huge sums in the EV transition are making changes to try and keep sales going in America. Hyundai, for example, announced in early October that it will cut the price of its popular Ioniq 5 EV by nearly $10,000 next year. One week later, General Motors unveiled a $29,000 version of its Chevy Bolt.

Some state and local governments are taking action, too: Colorado boosted the discounts it offers for both new and used EVs. Burlington, Vermont, launched a similar program.

Meanwhile, the country’s public EV charging network is growing steadily, and the Trump administration is moving ahead with a $5 billion Biden-era program to build out charging infrastructure.

It’s clear, as Cox points out, that electrified vehicles are the future of transportation. Indeed, some countries are already living in that era: In Norway, more than eight in 10 new cars sold are fully electric. The roadblocks set up by the Trump administration might delay progress in the U.S., but it can’t stave off the inevitable.

Earlier this year in tiny Liberty, North Carolina, a multibillion-dollar Toyota plant began shipping batteries for use in the auto giant’s hybrid and electric vehicles. Expected to ultimately create at least 5,000 jobs, the facility is the largest investment to date in the Southeast’s burgeoning “battery belt,” which leads the nation in plans for the manufacturing of electric vehicles and their components.

The Liberty plant — along with other projects in the EV supply chain — was a bright spot in a recent assessment of the region’s electric transportation sector, which also highlighted record growth in EV sales and rapid deployment of fast chargers. The question is whether that momentum can survive gale-force federal headwinds, including today’s expiration of tax credits for EV buyers.

The two groups behind the report, Southern Alliance for Clean Energy and Atlas Public Policy, say the answer now depends on key players outside of Washington, from utilities to consumers to automakers. But the organizations cast themselves as cautiously optimistic.

That may seem counterintuitive given that congressional Republicans, led by President Donald Trump, have dealt blow after blow this year to the policies meant to hasten the nation’s shift to clean transportation.

Generous tax credits for purchasing new and used electric passenger cars now end Sept. 30 instead of in 2032, as do inducements to buy commercial EVs, thanks to the GOP budget bill signed into law this summer. The measure also scales back incentives for manufacturing EVs and their components, like batteries.

In May, Congress voted to revoke California’s long-held authority to set its own tailpipe pollution standards, which have nudged automakers away from combustion engines and created demand for EVs nationwide. Trump signed the legislation in June.

At the same time, the Trump administration has moved to roll back the national version of those tailpipe rules and stalled the nationwide buildout of electric vehicle charging infrastructure — which was authorized in bipartisan fashion in 2021.

There are few state policies in the Southeast to counteract this federal backsliding. In fact, due to added registration fees and the like, EV owners across the region pay more into state coffers than do owners of combustion vehicles who drive the same amount. Of the six states covered in the new report, from North Carolina to Alabama to Florida, only the latter has no such punitive fees.

Advocates involved with the analysis are clear-eyed about these roadblocks for passenger EVs. But they also say there is cause for guarded hope — starting with consumer behavior.

The fact remains that EVs are gaining popularity in the region, growing in market share in each of the six years that the report has been produced. EV sales in Florida — hardly a bastion of clean-energy policy — have led the way, making up more than a tenth of new car purchases in the first half of 2025, above the national average. The state’s mild temperatures and flatlands are especially conducive to EV driving, but the growth is still telling.

What’s more, drivers appear relatively undeterred by state EV taxes. Florida leads the region, but Georgia and North Carolina are neck and neck in EV adoption, even though the former has higher fees.

“There’s no clear correlation between those taxes and buying an EV,” said Stan Cross, electric transportation program director at Southern Alliance for Clean Energy and a report author.

Publicly accessible charging ports are also rising sharply across the region, with fast chargers jumping 41% and slower Level 2 chargers increasing by 24% over the last year, according to the study. That growth appears poised to continue. After what critics said was an illegal pause by the Trump administration, money for the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure program is set to start flowing again. As soon as it does, Cross predicts quick action.

“States have already done the planning, and EV charging companies and the businesses hosting the chargers are chomping at the bit to compete for contracts, get the stations in the ground, and meet the charging demands of eager EV drivers,” Cross said.

The deployment of EVs aligns with the self-interest of the investor-owned monopoly utilities that dominate the region: Electric vehicles can both increase their sales and provide other benefits to the grid. For instance, plug-in cars and buses can act as batteries, storing power that can be discharged during times of high demand. Outlays by Southeastern utilities experimenting with these uses have lagged behind those in the rest of the country — representing just 7% of the nation’s $6.6 billion in approved investments. But utilities in the region, say advocates, are at least moving in the right direction.

Perhaps more than any other player, the automakers themselves will make the biggest difference in how EV deployment unfolds — in the Southeast and across the U.S.

One decision automakers face is on the front end: Do they retreat from, or double down on, the investments they’ve already made in battery and electric vehicle production? The report notes that companies have already canceled plans for seven facilities in the region, worth a total of $3.5 billion, in the last year. But others are proceeding more or less as planned, including the Toyota facility in Liberty.

If major carmakers continue their commitment to produce vehicles and their components in the United States, consumers will likely benefit from lower prices.

“The most expensive part of an EV is the battery,” said Matthew Vining, policy analyst at Atlas Public Policy and an author of the report. The Liberty plant, he noted, has already made Toyota cars produced in the U.S. more affordable.

That trend could persist since Congress spared incentives for battery manufacturing from devastating cuts in this summer’s budget law.

“From the federal government, there’s actually a good amount of support for the battery and the critical minerals industry,” Vining said. “That will have a downward pressure on the price of the vehicles, making them more appealing to drivers.”

Automakers also face choices on the back end. Riding high off a burst in sales from buyers rushing to take advantage of the expiring tax credit, they may keep their prices low for a while longer.

No matter what, transportation is electrifying across the globe. One in four new cars purchased this year will be electric, Vining said, and China already has about 60% of the market. The question is whether carmakers in the United States will try to catch up or retrench to fossil fuels, he said.

“Are these automakers going to rise to the challenge?”

Electric trucks can beat diesel-fueled ones on the cost of moving freight from California’s seaports to its inland distribution hubs — as long as the battery-powered vehicles can reliably recharge at both ends of their route. That fact is spurring a boom in the construction of truck-charging depots across the state.

On Thursday, EV Realty, a San Francisco-based charging site developer, broke ground on what will be one of California’s biggest fully grid-powered, fast-charging depots for electric trucks so far.

The company’s site in San Bernardino, located in a region known as the Inland Empire that’s crowded with distribution warehouses, will pull about 10 megawatts of power from the grid once it’s up and running in early 2026. It will be equipped with 76 direct-current fast-charging ports, including a number of ultra-high-capacity chargers capable of refilling a Tesla Semi truck in 30 minutes or less.

EV Realty has more large-scale depots in the works, including another in San Bernardino, one in Torrance near the Port of Long Beach, and a fourth in Livermore in Northern California. Thursday’s groundbreaking was accompanied by the announcement that the company had raised $75 million from private equity investor NGP, which also led a $28 million investment in 2022.

With that cash infusion, along with last year’s debut of a joint venture with GreenPoint Partners to develop $200 million in charging hubs, “we are fully capitalized against an underwritten, five-year business plan,” EV Realty CEO Patrick Sullivan told Canary Media.

That plan includes “five to seven more projects of the scale we have in San Bernardino, plus some smaller, more built-to-suit projects,” he said.

EV Realty does build and operate sites for passenger vehicles, such as the chargers it installed in a parking garage in Oakland, California, backed by power provider Ava Community Energy. But the company isn’t in the business of setting up open public charging sites that depend on drive-by traffic to earn money back, Sullivan said.

Instead, it’s signing deals with major freight carriers and fleet owners that want a dedicated spot to get their trucks charged and back on the road as quickly as possible.

That’s why EV Realty’s 76 chargers at its San Bernardino site are all dedicated to specific customers, he said. Of those, 72 are committed to those paying monthly rates on multiyear contracts. “Our customers will have stalls and amounts of power that are theirs 24/7, and we will have customers basing their operations out of that site,” he said.

The remaining four chargers, including those offering high-voltage megawatt charging systems, are “pull-through” slots where trucks towing trailers can get a quick recharge. “That pricing will be more of a pay-as-you-go, per kilowatt-hour — but all those trucks are registered at our site,” he said.

EV Realty is far from the only business building megawatt-scale truck-charging sites in California. Big EV truck depots are springing up around Southern California’s massive port complexes and along its major freight corridors, built by startups such as Terawatt Infrastructure, Forum Mobility, Voltera, WattEV, and Zeem; freight haulers like NFI Industries and Schneider National; and logistics operators such as Prologis.

Most of these depots are providing dedicated service to customers under contracts, but a few are starting to offer charging on a first-come, first-served basis. Greenlane, a joint venture of Daimler Truck North America, utility NextEra Energy, and investment firm BlackRock Alternatives, opened a 10-megawatt truck-charging site in Colton, a city neighboring San Bernardino, that’s meant to provide a more traditional “truck stop” service to vehicles needing to charge.