In the far reaches of Appalachian Ohio, DeepRock Disposal Solutions and other companies pump salty, hazardous waste from oil and gas fracking thousands of feet underground at high pressure. Last year, the state gave DeepRock permits to drill two more injection wells for pumping such waste underground. The new wells are slated for rural Washington County, which sits on Ohio’s southeast border.

The state’s approval has drawn fierce opposition from surrounding community members and local governments that fear waste from the wells could escape and pollute their drinking water supply. Leaks have happened before, including from some DeepRock wells. But these opponents haven’t been able to stop the company’s latest drilling plans.

This lack of local authority highlights an unfair discrepancy in Ohio, according to legal experts and clean energy advocates: While state law allows counties, townships, and disgruntled residents’ groups to delay or even doom many solar and wind developments, it blocks almost all local decision-making power over fossil fuel endeavors.

The difference between how Ohio law deals with renewables and petroleum “is night and day,” said Heidi Gorovitz Robertson, a professor at Cleveland State University College of Law.

On one hand, state law gives the Ohio Department of Natural Resources “sole and exclusive authority” to permit oil and gas activities. “So the local governments are cut out entirely,” Robertson explained, noting a 2015 Ohio Supreme Court decision that held that the state’s comprehensive regulation of oil and gas activities preempts even city zoning ordinances that would otherwise restrict that work.

On the other hand, a 2021 law lets counties ban new solar and wind development for most of their territory. Even for “grandfathered” projects that are technically exempt from such bans, the Ohio Power Siting Board has used opposition from local governments as grounds for finding such developments were not in the “public interest.”

“What you have looks like total inconsistency” when it comes to deciding which energy projects should go where, Robertson said.

That has serious implications for the energy transition: It holds back the projects that would slash planet-warming and health-harming pollution while further entrenching the lead that the oil and gas industry has in Ohio’s electricity sector.

Ohio also treats renewables differently than it does fossil fuel projects when it comes to letting the community participate in permitting decisions. The state lets disgruntled residents intervene as official parties in wind- and solar-permitting cases, which allows those individuals to appeal permit approvals to the Ohio Supreme Court. Yet residents cannot intervene or appeal in cases about where oil and gas activities go.

Advocacy groups such as the Buckeye Environmental Network say this imbalance is making communities like Washington County, where DeepRock plans to inject more fracking waste, less safe.

Fracking — a drilling technique to extract fossil fuels from rocks thousands of feet deep — produces millions of barrels of waste per year. Regular wastewater treatment plants can’t handle those super-salty fluids, which can contain heavy metals, radioactive chemicals, and company “trade secret” compounds. That’s why the waste is typically disposed of in deep wells.

Ohio had more than 200 active fracking-waste injection wells as of late 2024, with several already in Washington County.

Marietta, a city of about 13,000 on the Ohio River, abuts Warren Township, where DeepRock will drill the new wells. The city’s leaders worry that the waste could migrate out of the rock layer where it will be stored. A 2019 investigation found that waste had escaped from another injection well in Washington County, although it wasn’t discovered in drinking water at that time.

The Marietta City Council passed a resolution in October that noted problems with waste escaping from other wells, and it urged the state to place a moratorium on disposing of more fracking waste in the area. The city also tried to appeal one of DeepRock’s permits, but the Division of Oil and Gas Resources Management at the Department of Natural Resources responded that its Oil and Gas Commission, which reviews those administrative appeals, lacks jurisdiction for Marietta’s claims.

“People are saying we don’t want these injection wells,” said Roxanne Groff, an advisory board member of the Buckeye Environmental Network. “And the main reason is the water.”

Groff’s group is taking another approach to stopping the DeepRock project: It’s suing leaders at the Ohio Department of Natural Resources over the permits issued for the wells. The lawsuit, filed in November, argues the agency illegally relied on outdated regulations that were in effect when DeepRock first filed for its permits but that were replaced in 2022 by stricter rules meant to better protect public safety and health.

“The law is very clear in our view that [the department] should be applying the rules in place at the time of permitting,” said James Yskamp, a senior attorney at the nonprofit Earthjustice, which is representing the Buckeye Environmental Network. When DeepRock applied for its permits in late 2021, the current siting rules were already in draft form, and the public comment period on them had ended. Moreover, the agency didn’t complete technical reviews, provide public notice about the permits, or accept comments on them until last year.

Karina Cheung, a spokesperson for the Department of Natural Resources, said her agency has no comment on pending litigation. But she did note that any permit to operate the wells after they’re drilled will need to comply with current rules in the Ohio Administrative Code. That permit would control how the company pumps waste underground under pressure, but not where that waste goes. And the wells would already have been drilled.

Lawyers for the officials at the Department of Natural Resources and for DeepRock want the case dismissed. The department had no duty to apply the current law, the filings claim. And any harm is speculative, they argue, because it wouldn’t happen until after fracking waste is pumped down.

The Buckeye Environmental Network’s petition before the Franklin County Court of Appeals indicates the two DeepRock wells are approximately 2 miles from protected groundwater resources for people in the city of Marietta and Warren Township. Already-operating wells in the area pump tens of thousands of gallons of fracking waste underground each day. Injecting yet more fluids under high pressure could cause waste to migrate out of deep rock layers and up through rock fissures, abandoned wells, or other conduits, the group alleges.

These concerns are founded on evidence, Groff noted, unlike people’s objections to solar projects, which she said tend to be lacking in factual support or based on false information.

Robertson at Cleveland State has the numbers to back up that claim: She analyzed the grounds for testimony against a utility-scale solar project in a permitting case in 2024. Most objections either had no basis in fact or had already been addressed by permit conditions. The rest were statements of opinion.

To the extent there is any consistency in how Ohio treats different types of energy projects, “it’s that the oil and gas industry wins every time,” Robertson said. “The oil and gas industry benefits by blocking local voices in oil and gas industry decisions. And the oil and gas industry benefits by having local voices involved in the wind- and solar-energy decision-making.”

The Trump administration is going after gas bans in two California cities.

Last week, the federal government sued to block the San Francisco Bay Area’s Morgan Hill and Petaluma from prohibiting the use of fossil gas in new buildings. Both have populations of less than 60,000.

The complaint, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, alleges that the restrictions violate a 1975 federal law that governs appliance efficiency standards. Climate advocates decried the move as federal overreach.

“Mayors and the people who elect them should decide the type of energy that powers the future of their communities,” Kate Wright, executive director of Climate Mayors, said in a statement. “The Justice Department’s lawsuit does nothing but tie the hands of local leaders who seek to help families find relief from high energy prices.”

More than 150 local governments have adopted some form of zero-emissions standards for new buildings, from banning gas outright to encouraging electrification. Such rules can benefit not only households’ comfort, health, and resilience but also their pocketbooks. Depending on local factors such as weather and energy costs, residents could save thousands of dollars over the lifetime of their homes’ superefficient electric appliances.

Why did the Trump administration target Morgan Hill and Petaluma? “I see it as part of a … broader harassment campaign between the federal government and states and cities that it’s unhappy with,” said Amy Turner, director of the Cities Climate Law Initiative at Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.

In April 2025, President Donald Trump signed an executive order requiring the attorney general to identify state and local laws “burdening the … use of domestic energy resources” — namely fossil fuels, not local solar or wind — and take “all appropriate action” to stop their enforcement.

Empowered, the Department of Justice sued four Democrat-led states last year: New York and Vermont to block Climate Superfund laws, which would make oil and gas producers pay for their greenhouse gas pollution; and Hawaii and Michigan to prevent them from suing fossil fuel companies for climate damages. The cases are ongoing.

Now the administration is attempting to crush municipal efforts to curb fossil fuel use in buildings. But whether the Department of Justice’s lawsuit will be viable remains in doubt, Turner explained. “There are some really significant questions around whether the federal government has standing to bring this case.”

Morgan Hill’s and Petaluma’s ordinances — passed in 2019 and 2021, respectively — are essentially relics of a laxer era when gas construction across California went largely unchecked, according to Matt Vespa, senior attorney at the nonprofit Earthjustice.

“California’s really moved on,” he said. “We have a very strong state code now [that’s] pushing buildings to be all-electric,” making it less important that cities themselves block gas hookups.

The Golden State’s latest building standard, which took effect Jan. 1, encourages gas-free construction more vigorously than ever, according to Vespa. The code is also technology-neutral, stopping short of banning new gas connections.

Instead, the rules require developers to meet specific efficiency standards, which are based on the performance of electric heat pumps, he said. Heat-pump appliances are about two to five times as energy efficient as gas furnaces and water heaters.

Developers could choose to install gas in their buildings anyway. But for an edifice to pass muster, it would need more efficiency improvements, such as a thicker jacket of insulation or triple-pane windows. Plus, the code requires that certain new buildings equipped with gas also be “electric-ready,” meaning they have the electrical service and wiring required for the structures to eventually go fully electric.

California is also shifting the economics of gas and all-electric construction. In 2022, the state nixed subsidies for gas lines to new buildings; and in 2024, it eliminated electric-line subsidies to mixed-fuel construction. What’s more, developers of all-electric homes can claim incentives of $1,400 to $5,500 per gas-free unit through the California Electric Homes program, which still has $24 million in its coffers.

In its court challenge against Morgan Hill and Petaluma, the Trump administration is using the same premise that struck down Berkeley, California’s pioneering gas ban in 2023.

In California Restaurant Association v. Berkeley, a three-judge panel for the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the 1975 Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA) preempts the city’s ban on gas hookups. The court’s reasoning, in brief, is that because this federal law prevents jurisdictions from deploying differing standards for the energy use and efficiency of covered appliances, it invalidates local bans preventing the use of gas appliances.

If you’re confused, you’re not alone. Many judges have found the EPCA argument flawed, even in the Berkeley case. When the three presiding judges decided not to authorize a rehearing en banc with a larger panel of judges in 2024, 11 circuit judges dissented. It was an unusual move, rarely done.

“In nearly a decade on the bench, I have never previously written or joined a dissent from a denial of rehearing en banc,” wrote U.S. Circuit Judge Michelle T. Friedland. “I feel compelled to do so now to urge any future court that interprets the Energy Policy and Conservation Act not to repeat the panel opinion’s mistakes.”

The opinion misinterpreted EPCA, she continued: “EPCA’s preemption provision guarantees uniform appliance efficiency standards. It does not create a consumer right to use any covered appliance” — such as a gas furnace.

In recent court battles invoking EPCA, judges have upheld the local laws restricting fossil fuel in new buildings in New York and New York City. These lawsuits — and many others brought on the same premise — continue to move through the courts. (In November, New York elected to pause its all-electric building standard, which would have taken effect at the end of 2025, for unrelated reasons.)

In the meantime, some towns have shifted to other tactics that encourage all-electric construction. New York City, for example, set an emissions limit of 25 kilograms of CO2 per million British thermal units that doesn’t explicitly prohibit gas use.

Regarding the future of all-electric buildings in Morgan Hill, Petaluma, and the rest of California, Vespa is sanguine.

“We see very high percentages of buildings going all-electric already,” he said. “Nothing about this lawsuit is going to change that.”

U.S. carbon emissions increased in 2025, even as clean energy installations surged.

Economy-wide emissions rose by 2.4%, according to a new analysis of federal data by the research firm Rhodium Group. This ended a two-year streak of emissions reductions and clocks in as the third-largest emissions increase in the last decade. The country is still emitting 18% less than it did in 2005 (compare that to President Barack Obama’s goal of a 26% to 28% reduction by 2025), but the economy has resisted a smooth glide toward decarbonization.

“It’s not the most notable increase that we’ve seen, but in the context of this bumpy downward trend, it is an up year,” said Rhodium Group research analyst Michael Gaffney.

Some of that emissions increase came from factors that Gaffney referred to as statistical “noise,” namely a very cold winter that pushed up space-heating needs in buildings. That kind of variation is to be expected. But changes in the power sector could be more potent signals of things to come.

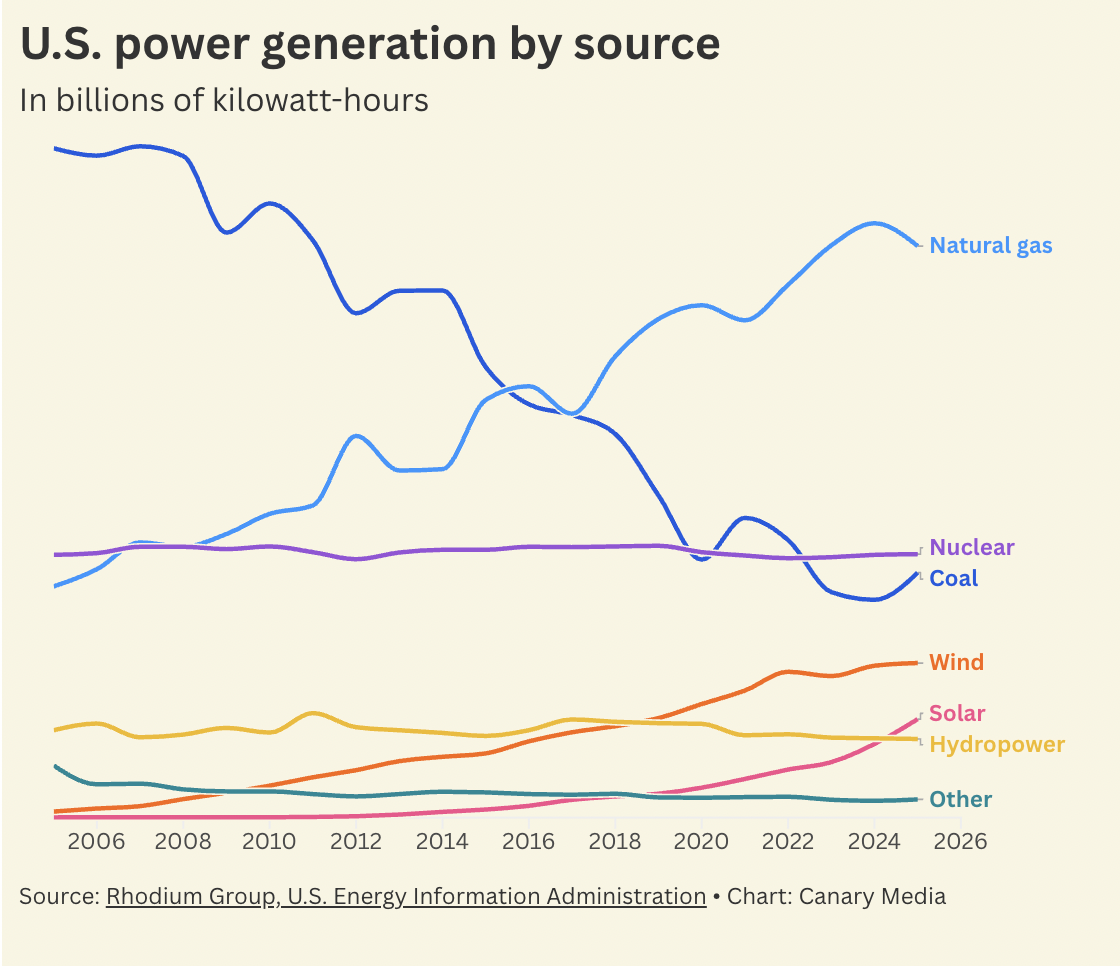

The power sector has generally led the U.S. economy in emissions reductions, largely because gas plants have outcompeted coal plants over the last two decades, and gas emits less carbon when burned than coal. But in 2025, coal proved that it’s not dead yet. Natural gas prices rose by 58% over 2024 levels, under pressure from space-heating demand and global exports via liquefied natural gas terminals. At the same time, demand for electricity soared: Generation increased by 2.4% from the year before, as data centers, crypto miners, and electric vehicles consumed more energy.

Taken altogether, the rise in demand at a time when gas was less economically competitive gave coal an opening in the markets, and its generation surged by 13% in 2025.

“This year is a bit of a warning sign on the power sector,” Gaffney said. “With growing demand, if we continue meeting it with the dirtiest of the fossil generators that currently exist, that’s going to increase emissions.”

AI data center demand shows every sign of increasing far beyond 2025 levels in the years ahead. That’s while export capacity for liquefied natural gas is on track to double by 2029, greatly expanding competition for U.S. gas supplies. The Trump administration has issued a flurry of “emergency” orders to block coal plant retirements, and many utilities are also choosing to push back planned coal plant closures as they respond to the sudden growth in power demand, Gaffney said.

Coal generation has plummeted by 64% from its peak in 2007, but it has rebounded for brief periods along that trajectory. 2025 offered a reminder that coal isn’t on a one-way street to obsolescence. Even without new coal plant construction, existing plants can ramp up operations when the opportunity arises, and could well continue to do so over the next few years.

The data from 2025 also challenges another truism in climate advocacy circles: that breakthroughs in climate technologies have decoupled economic growth from emissions growth. Last year, though, emissions increased faster than real GDP, which grew by a projected 1.9%, per Rhodium.

“Were this to persist, this would be a troubling sign for the broader transition, just because we’ve predicated this whole thing on ‘you can grow the economy without exploding emissions,’” said Ben King, Rhodium’s director of U.S. energy projects.

The brightest spot for decarbonization came, not surprisingly, with the wild success of solar energy. The power industry is building more gigawatts of solar than any other type of plant, and that construction pushed solar generation up by 34%.

“We did see a record year for solar generation last year — but for that, we would be in a much worse position from an emission standpoint,” King said.

However, solar is growing very fast from a small baseline, and on a national level, it still lags behind natural gas, nuclear, coal, and wind in total generation. Without the tremendous solar build-out, utilities might have burned even more coal. But solar alone couldn’t satisfy the growing demand for electricity last year.

Looking ahead at the durability of these trends, King said, “the question is, to what extent can policy actions continue to suppress that solar growth?”

Solar installations last year rolled forward on momentum created by supportive Biden-era policies. But the second Trump administration has taken numerous actions to block or slow renewable power plant construction. If those efforts succeed in slowing the pace of solar development, and power demand and gas prices remain high, the country could be on track for more emissions increases in the years to come.

Hyundai Motor Group is building a facility at an existing steel plant in South Korea to test out its technology to produce direct reduced iron before opening its flagship project in Louisiana.

Last week, the automaker announced plans for a pilot-scale DRI plant at its Dangjin Steelworks in South Chungcheong province, southwest of Seoul. The facility already operates a coal-fired blast furnace, a basic oxygen furnace, and an electric arc furnace, which makes steel from recycled scrap metal.

But DRI, a cleaner method of making iron that relies on gas or hydrogen to turn ore into iron, instead of a more polluting blast furnace, was until now missing from the mix. Construction on the DRI facility has already begun. Once it’s complete, the facility will have the capacity to produce 30 kilograms of molten iron per hour and will provide key technical data to help inform the future U.S. operation; by contrast, a typical blast furnace can produce tens of thousands of kilograms of molten iron per hour.

Reports in the Korean newspaper Chosun Biz and the trade publications Hydrogen Central and Fuel Cell Works indicate that the DRI pilot will use hydrogen as the fuel for the iron-making process. While it’s not clear what kind of hydrogen Hyundai plans to use in South Korea, the company has said its debut steel plant in Louisiana will depend, at least for the first few years, on blue hydrogen, the version of the fuel made with gas equipped with carbon-capture equipment. In the mid-2030s, however, Hyundai intends to swap blue hydrogen for the green version, made with electrolyzers powered by carbon-free electricity.

Hyundai did not respond to emailed questions from Canary Media.

The Louisiana project, set to come online by 2029, will be the most significant clean steel facility in the United States. Hyundai has invested heavily in the U.S. as the South Korean automaker faces increased competition in Asia from Chinese car companies. In the U.S., automotive manufacturers are the largest consumers of primary steel. Since President Donald Trump returned to office last year, American steelmakers have largely doubled down on older, dirtier methods of making the metal.

That’s a problem for automakers that have pledged to curb emissions. Hyundai, for instance, has a goal of carbon neutrality by 2045. To ensure a supply of clean steel, Hyundai is charging ahead with its own plant, despite recent challenges from the Trump administration.

“We’re taking the positive view that they’re making this investment in South Korea,” said Matthew Groch, senior director of decarbonization at the environmental group Mighty Earth. “This is a good sign that they’re committed to clean operations in Louisiana.”

BYTOM, Poland — Adam Drobniak pulled into the parking lot of a convenience store and stepped out of his sedan into the overcast afternoon. A coal mine just across the street cast dust into the air as conveyor belts sorted the shards of black, burnable rock. Down the road, a goliath coking plant belched fire and thick clouds of steam as its roaring ovens cooked off impurities in the coal to refine it for blast furnaces. The air smelled burnt, and it was difficult to tell whether the sky was gray from clouds or smoke. Drobniak took out a silver case from his pocket and flashed a mischievous smile as he withdrew a hand-rolled cigarette, then dangled it from his lips and touched the flame of an old-fashioned Zippo to the tip.

“I spent decades around this,” he said, motioning to the surrounding area. “How much more damage can it do?”

Bytom is located in Silesia, an ethnically distinct province in southern Poland and the European Union’s biggest coal-mining region. Silesia still produces millions of tons of coal annually and has been extracting it from the ground for hundreds of years. The first state-owned coal mine opened about 20 minutes southwest of Bytom in 1791, when the region was controlled by Prussia. Over the next two centuries, the area was transformed into a key node in Central Europe’s industrial supply chain, with the third-largest gross domestic product of any province in the region, behind only the Polish capital of Warsaw and the Romanian capital of Bucharest. Coal became a way of life.

Now Silesia is figuring out the least painful way to kill the coal industry.

An economist by training, Drobniak has become something of a doctor administering palliative care.

Over the past five years, Drobniak, who works at Poland’s University of Economics in Katowice, Silesia’s provincial capital, has partnered with labor unions, local officials, and industry leaders on a “just transition” plan to shift Silesia away from coal without abruptly destroying the livelihoods of thousands of people whose families have worked in the industry for generations, spanning kingdoms, republics, communism, and capitalism.

That plan, which seeks to capitalize on an economic transition already underway in Poland and give workers the time and resources to adjust, has become something of a model for neighboring countries such as Romania and Bulgaria, which are struggling with their own transition away from coal. And, though the plan faces pushback from EU policymakers in Brussels and shifting priorities in Warsaw as different parties vie for national power, Poland seems to be moving in the right direction. Across the province, new industries — from manufacturing to technology — are booming.

However, development has not been evenly distributed. The economic gap between cities such as Bytom and Katowice has more than doubled in the past three decades. While Katowice teems with new buildings and businesses, Bytom represents what Drobniak called the “worst case” for the transition, a corner of Silesia unusually entrenched in coal and suffering from high poverty and unemployment rates as the industry shrinks. The city has lost nearly a quarter of its population since the early 2000s, with residents leaving in pursuit of better opportunities elsewhere. Indeed, the coal mine that was cranking away when Drobniak and I visited Bytom this fall was set to close in December. Most of the miners there will likely transfer to other coal mines in Silesia.

As in many parts of Europe, wind turbines line the horizon on the drive into Silesia. Solar panels glimmer on old stone roofs. Poland is racing to build its first nuclear power plant and is inking deals with virtually every major small-modular-reactor vendor in the U.S. and the United Kingdom. The country is even carrying out drilling experiments to see whether geothermal heat could replace coal in its district heating system. It’s no wonder why: Poland’s coal phaseout is set to kick up a notch this year, even as electricity demand is rising. But the size, history, and Europe-wide importance of Silesia’s coal industry put the phaseout on a different scale — making the steps the region is taking to avoid upheaval for workers especially consequential.

The Silesian coal industry’s first brush with death came three decades ago.

In 1996, Poland enacted sector-wide reforms meant to consolidate mines and privatize state-owned enterprises as the country transformed after the fall of the Soviet Union. Over the course of just a few years, the number of jobs in the mining sector plunged by 356,000. After Poland joined the EU in 2004, its economy grew rapidly and employment in the coal sector partially recovered. But it dipped again, by tens of thousands of jobs, during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic.

Poland’s overall wealth expanded as the country integrated into the EU. But the relationship also brought tensions. As Brussels imposed increasingly strict targets to cut emissions from power plants and phase out coal, many countries built up renewables backed by natural-gas-fired plants. Pipelines stretching westward across Europe from the bloc’s eastern border soon flowed with gas molecules from Russia, one of the world’s biggest producers.

Poland was reluctant to follow suit. Centuries of fighting off invasions from the east — including four decades under Moscow’s control as a Soviet satellite — left Poles wary of depending on Russia for fuel. When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022 and started throttling Europe’s gas supply, Warsaw’s continued reliance on coal seemed, to some extent, vindicated. However, even as the conflict underscored the risks of Russian gas, surging electricity demand across the EU and looming emissions-cutting deadlines only emphasized the need for Poland to find new sources of power.

To Silesia’s coal miners, the end is looking inevitable.

“We are fighting for our lives here,” Krzysztof Stanisławski, a lifelong miner, told me when I visited the headquarters of the Kadra trade union, which represents many of the region’s coal workers. “It’s a big problem. We are fighting, and we are losing.”

But there are degrees of losing. In July, Drobniak and members of the Kadra union had visited the British city of Newcastle as part of a tour of the U.K.’s former coal-producing regions. The location was fitting. The city in northeastern England was once a coal-mining capital whose product fueled the first phase of the Industrial Revolution. But in the early 1980s, then–British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher incapacitated the coal unions as part of the Conservative Party’s crackdown on organized labor, and the steady push toward cleaner sources of power shrank the industry. The final coal mine near Newcastle closed in 2005.

“We visited Newcastle to learn about what we should avoid in the future,” Drobniak said. “There were very poor provisions to support the people there. We saw it physically. The Newcastle area just seemed very degraded.”

Hoping that Poland could avoid a similar fate, Drobniak had already helped broker a deal with the national and provincial governments to phase out coal in waves. The talks started in early 2020, when government regulators invited a group of economists to prepare a report on what a just transition away from coal could look like. The economists came out with recommendations in May of that year and promptly began work on a national strategy in June, all while drafting regional plans for provinces such as Silesia.

To start, the agreement promised benefits to keep coal workers solvent. Under the plan, which took effect in 2021, workers can access free training to transition to other lines of work while continuing to receive some compensation from their mining jobs.

Workers who opt to quit the mining industry for good are entitled to a one-time severance payout of 170,000 Polish zloty ($47,000). Miners who are within four years of retirement and leave early can count on a salary equivalent to 80% of their typical annual earnings.

The deal that Drobniak helped broker set a deadline of 2049 for Poland’s final coal operations to shut down, years later than in many other EU nations. Not everyone supported the idea. Poland’s reliance on coal has rendered its air some of the dirtiest in Europe, shaving an average of nine months off its citizens’ lives. Its per capita greenhouse gas emissions are the fifth-highest in the EU, and Brussels has continued to pressure Poland to speed up its transition. Meanwhile, Warsaw is bristling at spending more money to keep the coal sector’s operations going for another 23 years.

Over coffee and cookies at Kadra’s modest offices on the outskirts of Katowice, in the shadow of idle smokestacks from now-defunct coal-fired plants, Grzegorz Trefon, the union’s head of international affairs, recalled a famous speech Nikita Khrushchev gave at the Polish Embassy in 1956, in which the Soviet leader vowed to defeat the capitalist forces of the world through patient confidence that “history is on our side.”

“That’s what we want,” Trefon said. “We want to win by time.”

The reference to a reviled Russian ruler drew chuckles among his compatriots in the room. Dariusz Stankiewicz, the regional government’s lead specialist on the transition from coal, stepped in to clarify what Trefon meant.

“This shows that when we are facing this in a very slow manner, our economy can transform itself and produce new workplaces,” he said.

Between 2005 and 2022, Silesia lost 55,000 jobs in the mining sector, according to government data. But the region added 160,000 jobs in other sectors during that same 17-year time period.

“If we slow down the process, the economy can cope with this problem and produce new jobs,” Stankiewicz said. “This is why I support this very slow phasing-out process.”

In Bytom, poverty is entwined with pollution. Men looking older than their years, with sinewy muscles and tattoo-covered torsos, arrive shirtless at the grocer to buy cases of beer or vodka after finishing midday shifts at the mine. Across the street from the coking plant, women visibly solicit customers for sex from the stoops of Soviet-era apartment blocks. Drobniak warned me to be ready to run if anyone seemed to be eyeing my camera.

A roughly half-hour drive east, on the northeast side of Katowice, is a neighborhood with similar-looking buildings but a dramatically different vibe. The cobblestone streets and old brick buildings of the Nikiszowiec Historic Mining District hark back to an earlier era when this part of the region was powdered with coal dust and ash from active mines and industrial sites.

Today, however, the district is spotless and filled with local tourists who come to see hockey games at its indoor rink, eat at upscale restaurants, and shop at its art galleries. A facility that once contained a major coal mine now serves as a hub for video game developers.

“This was not a place that people wanted to come to,” Drobniak said. “Now it’s hard to get a table at the restaurants here on a Friday night.”

Both Warsaw and Brussels have contributed to Katowice’s advancement over the past 20 years, as has celebrity academic Philip Zimbardo, the American social psychologist best known for the Stanford Prison Experiment, whose international work eventually led him to set up a nonprofit called the Heroic Imagination Project in the historic district in 2014. That organization worked to create employment opportunities for young people, and as conditions improved, the EU gave the city a grant of 200 million euros ($235 million) to help revamp industrial buildings for modern uses.

The starkest transformation, however, may be in the city center, where the newer industries that Silesia has attracted have flocked. While mining once accounted for more than half of the province’s gross domestic product, it now makes up a third, as factories producing automobiles, machinery, and electronics have popped up. Gleaming new office towers brandishing the logos of multinational consultancies rise between older brick buildings. Modern luxury condos with architecture one might expect in Miami or Tel Aviv but not Central Europe take up entire blocks of an otherwise quaint city. A grass-covered park swoops down to a vast, futuristic stadium built in the Soviet times. Once an area where coal was gouged from the ground, it is now a gathering space for entertainment and corporate events — part of why Katowice was recognized last year as Poland’s best city to live in.

But Katowice remains small compared with larger cities such as Warsaw and Krakow. To Drobniak, the future of Silesia should look something like Seoul or Tokyo.

A few years ago, researchers proposed the concept of the Metropolis GZM, short for Górnośląsko-Zagłębiowska Metropolia. Rather than a piecemeal approach to developing new industries in the patchwork of former coal-mining hubs that dot central Silesia, Metropolis GZM would unite the urban areas into one, interconnected with railways, bike paths, and corridors of tall buildings.

“In the entire surrounding area, we have about 2.5 million people,” Drobniak said. “We would be the biggest city in Poland.”

Merging would help solve one of the trickier elements of the transition. Bringing the entire region under one municipal planning organization would, in theory, help find ways to bridge the divide between thriving cities like Katowice and declining hinterlands like Bytom.

“People are afraid that they’ll lose their identities because they are connected by generations not with Katowice but with other cities like Bytom,” Drobniak said. “We’d like to put the discussion on a different level and say, ‘There is no Katowice. It will be something new.’ We don’t know what will be the name of this urban structure. But this is a must. We must do this. If not, we will be fragmented and separated, and the metro areas of Krakow and Wroclaw will attract young people from us.”

The critical thing, Drobniak said, is to revive the economy rather than push residents to leave, keeping the youths and workers who draw new industries and stemming the decline of Bytom and other cities.

In former American coal-mining hubs in Appalachia, such as West Virginia, generations of families remain entrenched despite the downward trajectory of the industry and the dangers of a polluted environment. But those roots are shallow compared with Poland’s, said Trefon. Miners in Silesia can trace their families in local history nearly twice as far back as 1777, when the U.S. was founded.

“My family lives here. There are churches with my relatives’ names going back 400 years,” he said. “That’s why we have so much connection to this land. It’s not possible to find another place to remake the mining industry. But we need to find a sustainable way for the development of new economic activity that will stay here.”

It might seem like a dicey time for building decarbonization in the U.S., where edifices and the energy they consume account for about a third of the nation’s annual carbon pollution.

Republicans in Congress have cancelled tax credits that would have helped households save big on clean energy upgrades. The Trump administration is dismantling federal building-decarbonization policies and trying to block states and cities from setting rules that restrict fossil fuel use in homes and businesses. Even some Democrats who once championed such mandates U-turned last year: Los Angeles’ mayor repealed an ordinance that most new construction go all-electric, and New York’s governor delayed a similar statewide law previously slated to go into effect last week.

These are very real headwinds, but they’re not the whole story. Several key barometers suggest that building decarbonization is poised to pick up speed as consumers grow more worried about energy affordability, installers get familiar with electric tech, and policymakers and building owners alike recognize the health, comfort, and financial benefits of ditching fossil fuels.

Let’s dive into seven indicators — and a few bonus figures — that show why the momentum behind climate-friendly buildings may be unstoppable.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the consumer price index for piped gas ballooned more than twice as fast as that for electricity, and nearly four times as fast as overall inflation for all tracked items. That makes utility gas one of the leading causes of inflation, which could give customers pause on whether to depend on the fuel in the future.

The price surge is partly thanks to the fact that the U.S. has been increasing its exports of liquefied natural gas, squeezing the domestic fuel supply and driving up costs at home, said Panama Bartholomy, executive director of the nonprofit Building Decarbonization Coalition.

Gas customers are also shouldering growing infrastructure costs. Utilities have massively ramped up gas-system spending since the 2010s — a result of increased safety investments in response to some high-profile explosions that decade, as well as a sense of urgency stoked by state climate laws, Bartholomy said.

“Many [utilities] view this as a race against time,” he noted in a December interview. “We now have 15 states since 2020 that have started future-of-gas proceedings, where they’re actually [taking] a regulatory approach to how they’re going to wind down the gas system in their state.”

In utility territories across 46 states and Washington, D.C., existing gas customers cover the cost of hooking up new customers to the system. The fees add up to $2 billion to $7 billion each year, according to an August 2025 analysis by the Building Decarbonization Coalition.

Policymakers and utilities in six states have reformed these “line extension allowances” to stop incentivizing growth of the gas system as well as to lower customer bills. Of the six, California, Colorado, and New York have eliminated the subsidies statewide. Another six states and D.C. are considering ending them.

Putting an end to gas-hookup subsidies is a fast-acting affordability measure, Bartholomy said. “States [that] stop subsidies in 2026 … are going to save people money in 2027.”

The majority of homes — both single- and multifamily abodes — are now built with electric heating, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That’s a big change over the last decade for single-family homes especially; in 2015, 60% were equipped with gas or propane heating, and just 39% were heated electrically.

Among multifamily buildings, electrically heated units accounted for 63% of new construction in 2015. In 2024, the share rose to 76%.

The agency doesn’t break down how many newly built homes have super-efficient heat pumps. But the next stat shows that the appliances are increasingly popular.

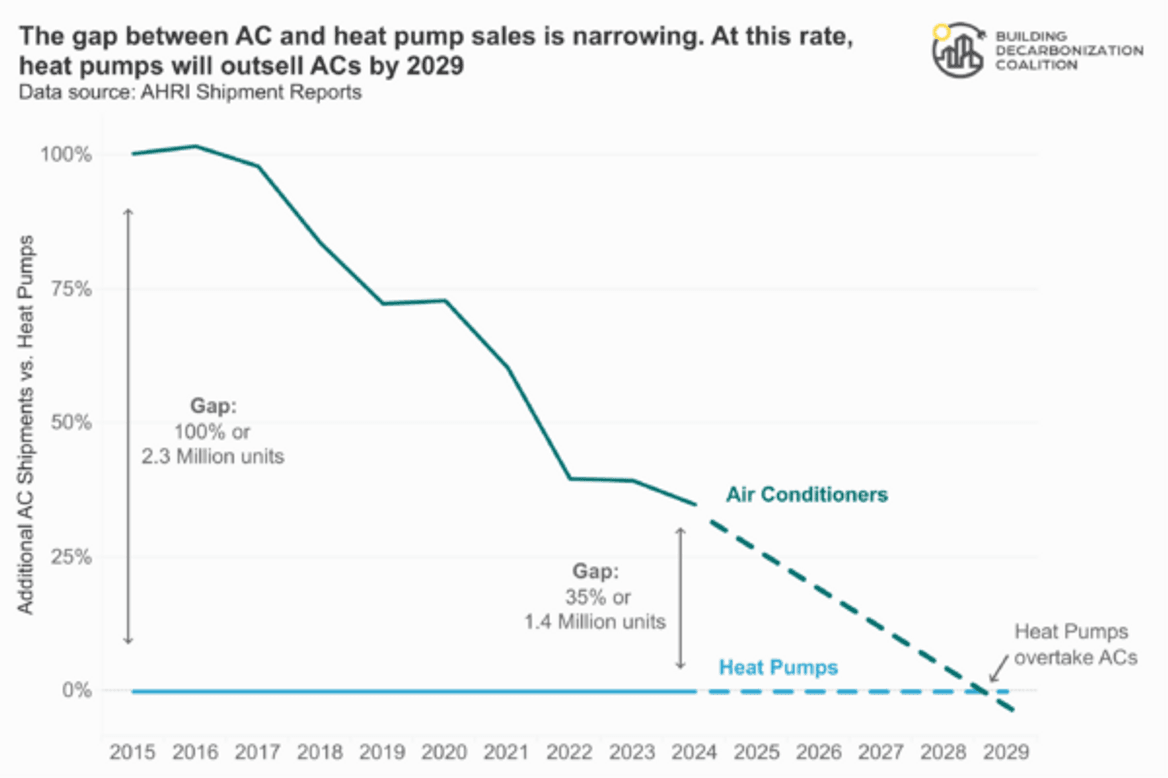

Heat pumps beat out gas furnaces (3.1 million shipped in 2024) by their biggest margin ever, 32%, that year, according to data from the industry trade group Air-Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute. The numbers for 2025 through October, the latest available, show heat pumps in the lead yet again.

These appliances, which provide both heating and cooling, are also steadily gobbling up the market share of conventional air conditioners. In 2015, ACs outsold heat pumps by two-to-one. By 2024, the gap had shrunk to 35%, with ACs still pulling ahead.

Bartholomy of the Building Decarbonization Coalition predicts that margin could shrink to just 20% in 2026.

Lawmakers in 13 states have approved bills that encourage gas utilities to reinvent themselves as utilities that provide carbon-free thermal energy instead of fossil gas. Some of these laws require gas companies to pilot thermal energy networks, which can decarbonize entire neighborhoods at once by replacing gas pipeline systems. Others unlock financing or establish regulatory frameworks that allow utilities to recover costs for these projects from customers.

Thermal energy networks that make use of geothermal heat, found tens to hundreds of feet deep, are also the rare climate solution that the federal government is incentivizing. Geothermal networks are eligible for a tax credit of 30% to 50% until 2033. The appliances that harvest underground heat and store it for later — geothermal heat pumps and thermal batteries — qualify for the tax credit, too, as long as eligible commercial customers lease instead of purchase these products.

“In many states, we’re seeing this lease [structure] as a real tipping point, where geothermal becomes less expensive than the status quo for the builders,” Dan Yates, CEO of geothermal heat-pump startup Dandelion Energy, told Canary Media last year.

That’s according to a survey released in January 2025 by the ACHR News. The same survey revealed that 71% of heating, ventilation, and air conditioning installers expect heat pumps to make up a larger fraction of projects in the next three years. Just 61% thought so the year before.

Contractors may be responding to warming consumer sentiment. About nine out of 10 heat-pump owners would recommend the tech to others, and a growing number of homeowners (32% in 2024 versus 23% in 2023) report having a good understanding of what these systems are, per a survey published in February 2025 by manufacturer Mitsubishi Electric Trane.

Innovation in some contractor businesses could also help the tech gain traction. One vertically integrated startup, Jetson, says it’s cutting the cost of heat-pump installations in half.

That nugget comes from the National Kitchen & Bath Association’s 2025 Kitchen Trends Report, according to a September Forbes story.

“I’m a big fan of induction,” Amy Chernoff, vice president of marketing at national retailer AJ Madison, told Forbes. Compared with gas cooking, an induction stove “keeps your kitchen cooler, it’s easier to clean, better for the environment, and much safer for households with children.”

The above numbers reveal how the markets for efficient, electric equipment — nudged along by policy — are steadily transforming. Let’s see if consumers, contractors, developers, advocates, and policymakers can keep up the building-decarbonization momentum in 2026.

The Environmental Protection Agency plans to let 11 coal plants dump toxic coal ash into unlined pits until 2031 — a full decade later than allowed under current federal rules.

The move tosses a lifeline to the polluting power plants. If the facilities were barred from dumping ash into unlined pits, they would be forced to close, since they can’t operate if they don’t have a place to dispose of the ash, and the companies say finding alternative locations for disposal would be impossible.

These 11 plants have already circumvented the 2021 deadline to close such pits, through a 2020 extension offer from the first Trump administration. By filing applications for that extension through 2028, the plants were allowed to keep running even though the EPA has yet to rule on the applications.

On January 6, the EPA held a virtual public hearing on its proposal to give the plants an additional three years to stop dumping coal ash in unlined pits. Attorneys, advocates, and people who live near the plants called the plan illegal, a threat to public health, and another tactic by the Trump administration to prolong the lives of polluting coal plants.

In recent months, the Department of Energy has ordered coal plants scheduled for retirement to continue operating, saying their electricity is needed — an argument the EPA echoed in its proposal. Some state regulators, grid operators, and energy experts have pushed back on the notion that it is necessary to force these power plants to stay online. At the hearing, critics of the EPA’s proposed extension said reliability concerns are outside the agency’s coal ash mandate to protect human health and the environment.

“If the proposal is not finalized, the plants would have to close their [coal ash] impoundments and cease burning coal by 2028,” said Lisa Evans, a senior attorney for the environmental law firm Earthjustice. But under the proposed extension, “the plants will continue to burn coal, thus creating additional air pollution,” and contamination from coal ash.

Coal ash dumped in unlined pits can leach into groundwater, potentially contaminating drinking water wells with carcinogens and other dangerous elements. In 2018, the federal D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the 2015 federal regulation on Coal Combustion Residuals (CCR) must be strengthened to better deal with such sites. The ruling led to an April 2021 deadline to start closing unlined coal ash ponds.

Through a 2020 extension offer from the first Trump administration, the EPA invited power companies to apply for the extension through 2028 if they had no other way to deal with the ash and were otherwise in compliance with the rules for disposal.

The EPA made a final decision in only one case, denying an extension to the troubled James M. Gavin plant in Ohio in 2022. But any company that filed an application has been able to keep its plant running while the EPA considers the case, something critics say is an obvious loophole.

The latest proposal would let three such plants in Illinois, two in Louisiana, two in Texas, and one each in Indiana, Ohio, Utah, and Wyoming operate until 2031.

“That [2021] deadline was established to stop ongoing contamination and protect communities,” said Cate Caldwell, senior policy manager of the Illinois Environmental Council, which represents 130 groups in the state. “By expanding a loophole created during the first Trump administration, EPA would allow coal plants to delay closure for at least three more years and potentially much longer.”

The EPA’s previous and proposed regulations say that an extension for unlined pits can be granted only if the site is in compliance with the federal coal ash rules, including those involving cleaning up groundwater contamination.

At the hearing, experts argued that the 11 plants are not in compliance. Groundwater monitoring data that the companies are required to provide shows that all the sites eligible for the extension have elevated levels of contaminants linked to coal ash.

“EPA never reviewed these demonstrations,” Evans said. “If they did, I am confident that they would likely find that each of the plants are ineligible for an extension.”

In the virtual hearing, Indra Frank, coal ash adviser to the citizens group Hoosier Environmental Council, told the EPA that the R.M. Schahfer plant in Indiana is violating the coal ash rules by failing to file the required groundwater monitoring reports and other documents for a retired coal ash pond, which she and Earthjustice attorneys discovered in reviewing maps and images of the site.

“That impoundment is subject to the federal CCR rule, but it has not met any of the requirements of the rule. To qualify for the extension offered in 2020, utilities were required to be in full compliance,” Frank said at the hearing. “Since Schahfer was not in compliance, Schahfer did not qualify for the extension in 2020 and should not receive the additional proposed extension.”

Schahfer’s two coal-fired units were scheduled to close in December, but the Department of Energy ordered the plant to keep running — though one unit has actually been offline since July in need of repairs. In an August email to the EPA, an official with the plant’s parent company said the coal ash extension would be necessary to justify spending money to get the plant back online.

Locals are dismayed that Schahfer may continue to run and say that no more coal ash should be placed in its unlined pond. Arsenic, molybdenum, cobalt, and radium have been found in groundwater near the pond, and the coal ash is held back by a dam with a high hazard rating, meaning its failure would be likely to cause death.

“We just see this proposed rule as a downright unlawful, reckless attempt by the Trump EPA to let polluters keep polluting,” said Ashley Williams, executive director of the advocacy organization Just Transition Northwest Indiana. She called the coal ash at the Schahfer site a “largely silent crisis that we’ve had to continue to sound the alarms on.”

Colette Morrow, a professor at an Indiana public university, told the EPA during the hearing that she suffers from an autoimmune disease and fears for her health if the Schahfer plant is allowed to keep running.

“This is unconscionable that the U.S government would put its own people at risk to such a high degree, only in order to enhance profits of these utility providers,” Morrow said.

Retired chemistry teacher Mary Ellen DeClue said she was shocked to learn about the contaminants that could be leaching into Illinoisans’ drinking water — since many rural residents tap private wells.

“This is not acceptable,” she said, imploring the EPA not to “rubber-stamp” the extension.

The three Illinois plants seeking the extension — Kincaid, Newton, and Baldwin — are owned by Texas-based Vistra Corp. The plants have already benefited from leniency under the Trump administration: Last year the company accepted the administration’s offer of an extension on complying with federal air pollutant limits.

Illinois is one of the states with the highest number of coal ash sites, according to data filed by power companies. Illinois coal plants will have to shut down by 2030 under state law, but each extra year of operation places residents at risk, local advocates say.

“Many of these communities rely on groundwater for drinking water and lack the resources to address widespread contamination on their own,” Caldwell of the Illinois Environmental Council told the EPA. “The agency should not be asking coal companies how long they would like to continue dumping toxic waste. It should be enforcing closure requirements that are already long overdue.”

The Trump administration’s campaign to force aging coal plants to keep running has entered a new phase: ordering broken-down units to come back online. Repairing those polluting plants could take months and cost tens of millions of dollars — all just to comply with legally questionable stay-open mandates that last only 90 days at a time.

In December, the Department of Energy ordered four coal plants — two in Indiana and one each in Colorado and Washington state — that were set to retire by year’s end to continue generating power for 90 days. Two of them have units that have been out of commission because of mechanical failure: Colorado’s Craig Generating Station Unit 1 has been down for three weeks and Indiana’s R.M. Schahfer Unit 18 has sat idle since July.

This means the utilities that own those plants must now race to bring them into working order, even though they’ve long ago deemed the facilities uneconomical to operate. Customers already grappling with skyrocketing electricity rates are likely to shoulder the costs of fixing and running the equipment. Complicating matters further is that the required repairs may not even be feasible to complete within the 90-day window covered by the DOE orders.

“Coal plants — and in particular the plants DOE has targeted — are these clunky old jalopies that, out of nowhere, just fail,” said Michael Lenoff, a senior attorney at nonprofit law firm Earthjustice, one of several environmental groups challenging the must-run orders. “DOE forcing these things to be available, and in some instances to run, actually creates reliability risk to the grid.”

The Trump administration claims that keeping the plants online is the only way to prevent blackouts in the near future. Last month’s must-run orders, as well as earlier ones forcing a Michigan coal plant and an oil- and gas-fired plant in Pennsylvania to stay open, were issued under Section 202(c) of the Federal Power Act, which lets the DOE compel power plants to operate to forestall immediate energy emergencies.

Critics say the Trump administration has weaponized this authority to prop up the U.S. coal industry, which provided about half the country’s generation capacity in 2001 but now supplies about 15%. None of the plants that the DOE has forced to stay open is needed for near-term reliability, according to the utilities, state regulators, and regional authorities responsible for maintaining a functioning grid. And despite its claims of an energy crisis, the federal government is throwing up roadblocks to wind, solar, and battery projects that are a fast and cheap way to add electrons to the grid.

The costs of the Trump administration’s coal interventions are mounting. The Sierra Club estimates that the price tag of keeping those six power plants running under the DOE’s orders has added up to more than $158 million as of this week.

And utilities that have to repair units before starting to generate power again will face a new set of costs.

In Indiana, Schahfer’s Unit 18 has been offline since July because of a damaged turbine. Vincent Parisi, president of Northern Indiana Power Service Co., the utility that owns and operates the plant, told Indiana state regulators in December, “It can take six months or longer for us to ultimately be able to get that unit back to where it would need to be to operate for an extended period of time.” Parisi did not provide cost estimates for those repairs or for extending operations at the Schahfer plant, and a NIPSCO spokesperson declined to provide an estimate to Canary Media.

In Colorado, Craig Unit 1 has been offline since Dec. 19 because of mechanical failure, according to Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association, the electric cooperative that operates and holds a partial ownership stake in the plant. “As a not-for-profit cooperative, our membership will bear the costs of compliance with this order unless we can identify a method to share costs with those in the region,” Tri-State CEO Duane Highley said in a December press release. “There is not a clear path for doing so, but we will continue to evaluate our options.”

Tri-State spokesperson Mark Stutz said the co-op and its partners don’t have firm cost estimates for repairs or for compliance with the order, “which will likely require additional investments in operations, maintenance, and potentially fuel supply.”

Consultancy Grid Strategies has estimated that keeping Craig 1 running for 90 days would cost at least $20 million, and that running it for a year could add up to $85 million to $150 million. Those costs do not include repairs of the equipment that failed and caused it to go offline.

Fixing up coal plants to comply with the DOE mandates could also put utilities in a legal bind. State attorneys general and environmental groups are already challenging many of the agency’s Section 202(c) orders, saying those orders are based on false premises and violate the law’s strictures for the agency to use its authority only to prevent immediate grid emergencies.

These arguments may soon see their day in federal court. In December, a coalition of environmental groups, including Earthjustice, filed a legal brief with the federal D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals challenging the DOE’s use of Section 202(c) authority to force the J.H. Campbell coal plant in Michigan to keep running. The brief asks the court to “put an end to the Department’s continued abuse of its authority, which has imposed millions of dollars in unnecessary costs and pollution on residents of Michigan and the Midwest.”

Nor does the DOE have authority to order utilities to undertake repairs or alterations to power plants under Section 202(c), Earthjustice, Sierra Club, and Indiana-based environmental and consumer advocates argued in a December letter to NIPSCO. The groups warned the utility that they plan to legally challenge any repair costs it tries to pass on to customers.

“The authority does not exist within Section 202(c) for DOE to force upgrades or major investments in energy-generating facilities. The authority only extends to operational choices,” said Greg Wannier, senior attorney for the Sierra Club. “I do think that at some point, regulated utilities do bear some responsibility for not taking illegal actions to comply with illegal orders.”

NIPSCO spokesperson Joshauna Nash told Canary Media that compliance with the DOE’s order is “mandatory.” The utility is “carefully reviewing the details of this order to assess its impact on our employees, customers, and company to ensure compliance,” Nash said. “While this development alters the timeline for decommissioning this station, our long-term plan to transition to a more sustainable energy future remains unchanged.”

The Trump administration seems set to continue using Section 202(c) authority. The DOE has issued three consecutive 90-day must-run orders for both the J.H. Campbell plant and the Eddystone plant in Pennsylvania. It has also issued a report that appears to lay the groundwork for justifying federal action to prevent any fossil-fueled plant from closing, citing data that critics say has been cherry-picked and misrepresented to paint a false picture of a power grid on the verge of collapse.

If the DOE continues to prevent fossil-fuel plants from closing, the costs could reach into the billions of dollars. Grid Strategies has estimated that forcing the continued operations of the nearly 35 gigawatts’ worth of large fossil-fueled power plants scheduled to retire between now and the end of 2028 could add up to $4.8 billion over that period.

Financial concerns aside, forcing utilities to react to successive 90-day emergency orders amounts to “sticking a wrench in the spokes of how utilities and their state regulators have planned their systems,” said Brendan Pierpont, director of electricity at think tank Energy Innovation.

The utilities under DOE must-run orders have developed plans to retire workers at those plants or move them to other jobs, he said. They’ve ended long-term coal-delivery contracts and procured alternative resources to make up for the lost power from the shuttering units. Some plan to convert the facilities to run on fossil gas, as is the case with the Schahfer plant and the coal plant in Washington state. Those projects will likely be delayed if the coal units must keep running, he said.

Earthjustice’s Lenoff agreed that the DOE’s intrusion into those plans is “creating uncertainty that harms investment, raises costs, and disrupts orderly planning by experts and authorities who know what they’re doing. The Department of Energy has shown that it is just blundering into markets and processes that it doesn’t understand with flimsy arguments that don’t withstand scrutiny. And other people are bearing the costs.”

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

Venezuela has the world’s largest oil reserves, but the South American country’s heavy oil deposits also stand out for another reason; on a barrel-for-barrel basis, they pack the most climate pollution.

Following the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro by U.S. forces, President Donald Trump said, in a social media post on Tuesday, that the country would turn over 30 to 50 million barrels of high quality crude oil to the U.S. However, Trump himself previously stated that Venezuela’s oil is “the dirtiest, worst oil probably anywhere in the world.”

Venezuela’s “extra-heavy” crude is a thick, tar-like substance that typically must be heated to bring it to the surface and diluted with other chemicals before it can move through pipelines.

“It takes a lot of energy to heat the stuff and get it out of the ground and then get it to move and flow, and then turn it into normal products,” said Deborah Gordon, senior principal in the Climate Intelligence Program and head of the Oil and Gas Solutions Initiative for RMI, a nonprofit focused on clean energy. “And every energy input means a lot of emissions.”

Greenhouse gas emissions from heavy crude oil production, refining and use are, on average, 1.5 times higher than those of light crude oil, according to a 2018 study published in the journal Environmental Research Letters. The study, co-authored by Gordon, assessed the climate impact of 75 different crude oils worldwide.

Heavy crudes are also low quality oils that require more refining, which further increases the energy used to bring the fuel to market and its associated emissions, said Adam Brandt, an energy science engineering professor at Stanford University and the lead author of the study.

Oil from Venezuela, the majority of which is extra-heavy crude, has the second-highest carbon intensity of oil from any country, a policy paper published in 2018 by Brandt, Gordon and others in the journal Science concluded.

An updated analysis by RMI’s oil and gas climate index, based on 2024 data, found that oil from Venezuela had the highest carbon intensity among 55 leading oil-producing countries.

“Just because this hydrocarbon exists doesn’t mean that it should be marketed or taken out of the ground,” said Gordon, who is the author of No Standard Oil, a book that looks at the varying climate impacts of different crude oils. “If there is demand, there are far better places to go than Venezuela.”

Leaks and intentional venting of methane gas associated with oil production in the country contribute to its outsized climate impact. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas. On a pound-for-pound basis, it is more than 80 times worse for the climate than CO2 over a 20-year period.

Venezuelan oil had the second-highest methane intensity among leading oil producing countries in 2023, according to the International Energy Agency. The country’s high leak rate is due in part to ongoing oil and gas sanctions, which have led to poor resource management, Gordon said.

A lack of proper maintenance has also led to frequent oil spills. Venezuela’s state-owned oil company Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A., reported more than 46,000 oil spills between 2010 and 2016. The company hasn’t reported any spills since then. However, in 2020, the head of Venezuela’s Unitary Federation of Petroleum and Gas Workers, a labor union, estimated that oil spills occur almost daily in some states.

Despite Trump’s pledge to open Venezuela’s oil reserves to U.S. companies, that may not result in increased production.

Simply maintaining current production levels in Venezuela would require $53 billion in new energy infrastructure investments according to an analysis released Tuesday by Rystad Energy, an independent energy research and business intelligence company headquartered in Oslo, Norway.

Kirk Edwards, president of Latigo Petroleum, an independent oil and gas producer based in Odessa, Texas, called the U.S. government’s recent actions in Venezuela a “nothing burger” for oil markets.

“This is not ‘drop a rig and up comes the bubbling crude,’” Edwards wrote on LinkedIn. “Any real turnaround would require $50–100 billion of sustained investment, modern infrastructure, and years of political stability.”

Edwards said companies are unlikely to make that investment given current low oil prices.

Gordon said Venezuela’s oil and gas sector will continue to have an outsized climate impact, whether production increases or remains in its current state of disrepair.

“They’re just basically throwing stuff into the air,” Gordon said of current methane emissions.

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

U.S. energy markets and policy are heading toward the equivalent of a multicar pileup in 2026.

The key factors are consumer frustration with rising energy prices, Trump administration policies that are making the problem worse despite promises to make it better and a growing awareness that investment in AI data centers is part of a bubble that could pop at any time.

I asked seven experts for their outlook on what we’ll be talking about in 2026 and almost all of them touched on this set of intertwined problems. Call it a crisis or a disaster. Or just call it terrible politics for the party in power ahead of November’s midterm elections.

Robbie Orvis, senior director for modeling at the think tank Energy Innovation, said he expects energy affordability to be the major issue of the year. He pointed to the rising wholesale price of natural gas and how that is likely to translate into higher utility bills, since gas is the country’s leading fuel for power plants and home heating.

“I don’t anticipate that people’s home energy bills are going to go down anytime soon,” he said.

The country’s benchmark price of natural gas has risen from an average of $2.19 per billion BTUs in 2024 to forecasts of $3.19 in 2025 (full-year figures for 2025 are not yet available) and $4.01 in 2026, according to the Energy Information Administration’s short-term outlook.

Gas prices are rising for many reasons, including an increase in exports of liquified natural gas, mainly to Europe, and growing demand from U.S. gas-fired power plants.

Orvis also highlighted the Trump administration’s policy of requiring old coal plants to remain online, even when their owners would otherwise have closed them for economic reasons. The administration has done this several times, citing the need to maintain the grid’s reliability during periods of high demand.

The result is that utilities are forced to operate plants they wanted to close, which are dirtier and more expensive than readily available alternatives.

Meanwhile, the least-expensive option for new power plants in most of the world is utility-scale solar. Even if we include the cost of batteries to allow solar to be stored for nighttime use, solar is a low-cost leader, as shown by research that includes a report last month from energy think tank Ember.

The federal government could respond to rising prices by rapidly building new power plants. But the country’s permitting system, supply chains and recent policy decisions are harming the ability to provide relief.

Some of these problems predate the Trump administration. But President Donald Trump has made things worse with executive orders that add restrictions on the development of wind and solar power, including a stop-work order in December that halted construction on five offshore wind projects.

Michael Webber, a professor of engineering and public affairs who studies energy at the University of Texas at Austin, puts this problem in the form of a question:

“Do we return to normal for permitting energy projects or will every project have to price in the risk that the president might impulsively cancel it?” he asked in an email.

He said this risk is a cost driver for developers that will be enough to stop some marginal projects and drive up rates for consumers.

Our crystal balls are not super precise on some topics. For example, several people said the investment in AI data centers and forecasts of rising electricity demand to power them are part of an investment bubble. But it’s unclear if this market will face its reckoning in 2026 or later.

The larger problem is that AI companies are spending tens of billions of dollars to build gigantic, energy-sucking data centers, often without clear plans for how these projects are going to make money.

“There’s a bubble, and what’s going to end up happening is there’s going to be a consolidation,” said Stephen A. Smith, executive director of the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, an advocacy group based in Knoxville, Tenn.

In a consolidation, the companies with the weakest business plans will go bust and the companies with viable plans and ample cash reserves will pick over the wreckage.

One of the main questions, Smith said, is how much consumers will need to cover the costs of unwise investments to power data centers.

The worst-case scenario would be if utilities make substantial investments to meet data center demand and the demand doesn’t fully materialize, leaving the costs to be paid by households and other consumers.

Some states, including Indiana and Ohio, have adopted rules to try to make data center developers assume much of this risk. But much of the country has yet to thoroughly explore what happens to utilities and their consumers in a data center bust.

State utility commissions have helped set the table for the affordability crisis by approving rate increases and spending that push the limits of what ratepayers can afford.

Commissioners, along with governors and members of state legislatures, “are finally taking heed of their policy missteps,” said Kent Chandler, senior fellow for the think tank R Street Institute and former chairman of the Kentucky Public Service Commission.

Chandler expects that some state-level discussions will focus on introducing competition in areas where utilities now have local monopolies, with the hope that market forces can help contain costs.

At the same time, states and regions that already allow competition in electricity and natural gas markets may go in the opposite direction and explore giving utilities more leeway to build power plants and pass costs on to consumers.

If this sounds disjointed, that’s because it is. The larger point is that officials will respond to frustration with rising prices by wanting to be seen as taking action.

The decision by Congress and Trump to eliminate consumer tax credits for electric vehicles will cast a pall on at least the first half of 2026 and maybe longer. The credit phaseout in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act last summer led to a sudden surge in EV purchases before the incentives expired at the end of September, followed by an expected drop-off in sales.

“We’re going to see sales be a bit more tepid,” said Mryia Williams, executive director of Drive Electric Columbus in Ohio.

The problem is that potential buyers “are not sure what’s going on with anything,” she said.

Automakers have some high-profile EVs coming this year, including the redesigned Chevrolet Bolt and the new Rivian R2. But some companies also are reducing and redirecting their funding for EVs, including Ford, which discontinued the F-150 Lightning pickup as a fully electric model and is replacing it with a gas-electric hybrid.

Williams has concerns that eliminating tax credits sends the wrong message to automakers and consumers at a time when other countries are moving ahead of the United States in building the vehicles of the future. That said, she remains confident that the world will make a near-complete shift to EVs, even if U.S. policymakers decide they want to move more slowly.

It’s normal for the party that’s not in power to gain seats in Congress in the first midterm election after a presidential election. And, considering that Republicans’ majority in the U.S. House is fewer than five seats, it would surprise nobody if Democrats win control of the chamber.

The larger questions are about the scope of Democrats’ gains, including whether the party will pick up enough seats to gain control of the U.S. Senate and make substantial progress in governor’s offices and state legislative chambers.

A big part of the answer will depend on how effectively Democrats communicate their agenda in terms of voters’ affordability concerns, said Caroline Spears, founder and executive director of Climate Cabinet, an advocacy group that supports pro-climate candidates in state and local races.

“Voters are angry about rising prices, and we have an undercurrent of instability in the economy that has become more of a feature rather than a bug in the last few years,” she said.

Spears’ organization is focusing on states such as Arizona, Michigan, Minnesota and Pennsylvania, where flipping just a few seats could make a big difference on climate and energy policy.

She highlights Arizona as a state with a huge upside in terms of Democrats being close to having enough control to unlock more of the economic benefits of solar power.

“The extreme anti-clean energy legislation we’re seeing out of the sunniest state in the country is just astonishing,” she said.

To underscore this point, she noted that Massachusetts has more solar power jobs than Arizona, a fact that should be upsetting to Arizonans.

Now it’s time for the closer: Amory Lovins, an engineer and cofounder of RMI, has done about as much as anyone to foster research and advocacy about energy efficiency and conservation.

I saved him for last because the discussion of rising energy demand should, and could, turn into one about the need for greater efficiency.

Efficiency can take many forms, including batteries with higher energy density, solar panels that can capture more sunlight and computer servers that require less electricity to perform the same tasks.

He expects to see progress in 2026 but thinks more about how actual progress compares to what could be achieved with the right investment, research and policy support.

The obstacles aren’t technical or economic, he said. They’re mainly cultural and institutional.

“This is not low-hanging fruit that you harvest and then it gets scarce and expensive,” he said. “This fruit has fallen off the tree and is mushing up around our ankles, rotting faster than we can harvest more.”

He didn’t discuss efficiency in partisan terms, but I will. We have a president who has taken steps to weaken government requirements that products become more efficient, casting this as a matter of consumer choice. Trump said in his “Unleashing American Energy” executive order that he is safeguarding “the American people’s freedom to choose from a variety of goods and appliances” including lightbulbs, dishwashers, washing machines, gas stoves, water heaters, toilets and shower heads.

While Trump said this is a consumer-friendly action that will save money, decades of research on efficiency standards show the opposite to be true. The Trump administration has said its actions on the standards will save $11 billion, but this is based on an estimate of the cost of the rules that doesn’t include savings on utility bills. If we consider the costs and benefits, the standards have a net savings of $43 billion, according to an analysis from the Appliance Standards Awareness Project.

So, in an election year amid an energy affordability crisis, one side is actively hostile to energy affordability.

Other stories about the energy transition to take note of this week:

Offshore Wind Developers Seek Quick Court Resolution to Allow Construction to Resume: Ørsted and Equinor, two of the companies building offshore wind farms, have gone to court to seek permission to resume construction of two large projects that were stopped by a Trump administration order, as Diana DiGangi reports for Utility Dive. This is in addition to Dominion Energy’s request that a court allow it to resume work on a separate offshore wind farm, which will be the subject of a hearing next week. Interior Secretary Doug Burgum had ordered a stop to construction last month, saying there is new evidence that offshore wind could pose national security risks, but he didn’t go into detail about the risks.

Negotiations on Permitting Reform Hit a New Roadblock: The Trump administration’s stop-work order for offshore wind has made Senate Democrats pause negotiations on a measure that would streamline the federal process for approving construction of new energy projects, according to Sen. Shelden Whitehouse, D-R.I., as reported by Kelsey Brugger of E&E News. Members of both parties have been working on this proposal, but there remain some major sticking points, including the fact that House Republicans want the legislation to favor fossil fuel projects and Democrats are asking for limits on the Trump administration’s ability to pick and choose which projects happen.

EVs Take a Back Seat at Consumer Electronics Show: The Consumer Electronics Show, taking place now in Las Vegas, has become a showcase for new EV models and technologies in recent years. But this year, automakers are not planning any major debuts of new EVs, signaling a shift in emphasis for manufacturers in response to the Trump administration cutting incentives for the vehicles, as Abhirup Roy reports for Reuters. Instead, much of the emphasis this year is on AI, robotics and self-driving vehicle technologies.

Inside Clean Energy is ICN’s weekly bulletin of news and analysis about the energy transition. Send news tips and questions to dan.gearino@insideclimatenews.org.