States are ramping up efforts to get residents to switch from fossil-fuel-fired heating systems to all-electric heat pumps. Now, they’ve got a big new tool kit to pull from.

Last week, the interagency nonprofit Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management, or NESCAUM, released an 80-page action plan laying out key strategies to turbocharge heat-pump deployment. Individual states are already putting many of these tactics to the test.

California, Colorado, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, and the District of Columbia together committed to ambitious heat-pump adoption goals last year. Washington state joined the pact last week. Their targets: By 2030, heat pumps will make up 65% of the sales of residential heating, air conditioning, and water heating equipment. By 2040, that percentage is to climb to 90%.

The goals are essential for addressing climate change. Buildings are directly responsible for 13% of U.S. carbon emissions, in part due to the fossil fuels burned on-site to heat indoor air and water. All-electric heat pumps can do those jobs running on clean power.

The NESCAUM action plan comes as the Trump administration clings tenaciously to fossil fuels. In recent months, the federal government has rolled back energy-efficiency standards for appliances, imposed chaotic tariffs that are raising costs for consumers, and put an early expiration date on the $2,000 federal tax credit that helps homeowners afford heat pumps.

Despite these headwinds, the report shows that “states are still finding creative ways to move forward,” said Emily Levin, policy and program director for NESCAUM.

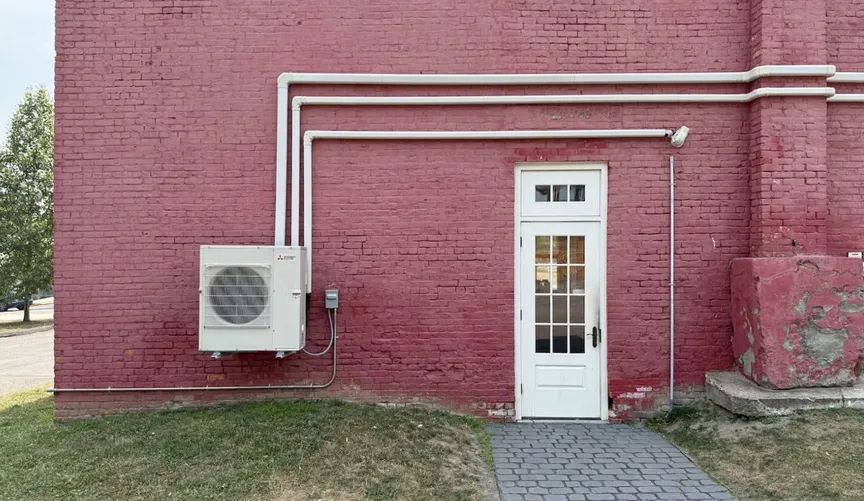

HVAC heat pumps are routinely two to four times as efficient as gas furnaces, capable of heating and cooling interiors using the same physics that refrigerators employ to chill your cucumbers. Heat-pump water heaters work the same way and are three to five times as efficient as gas water heaters. By eschewing fossil fuels, these technologies improve air quality and typically save people money over the long term, even if, on average, they cost significantly more up-front than conventional heating systems. (At least one startup, though, is trying to change that.)

Heat pumps are slowly catching on. In the U.S., the units outsold gas furnaces by their biggest-ever margin last year, but their share of the market is still modest. Citing data from the Air-Conditioning, Heating, and Refrigeration Institute, a trade association, Levin said that in 2021, heat pumps accounted for about 25% of the combined shipments of gas furnaces, heat pumps, and air conditioners, the three largest reported HVAC categories. In 2024, they’d risen to about 32%.

“No matter how you look at it, there are still a lot of gas furnaces being sold, there are still a lot of one-way central air-conditioners being sold — all of which could really become heat pumps,” Levin said.

Produced in consultation with state agencies, environmental justice organizations, and technical and policy experts, the NESCAUM report lays out a diverse set of more than 50 strategies — both carrots and sticks — covering equity and workforce investments, obligations to reduce carbon, building standards, and utility regulation. A wide range of decision-makers, often in collaboration, can pull these levers — from utility regulators to governor’s offices, state legislatures, and energy, environment, labor, and economic development agencies. Here are six recommendations from the report that stand out.

NESCAUM’s Levin stressed that the report is “a menu — not a recipe.” Each state will need to consider its own goals and constraints to pick the approaches that fit it best, she added.

Still, “I see [heat-pump electricity] rates as one of the areas that’s most promising,” Levin said. Massachusetts’ reforms “are really going to change their customer economics to make it more attractive to switch to a heat pump.”

When done right, rate design also avoids the need for states to find new funding. “You’re not raising costs on anybody, you’re only reducing costs,” Levin said. At a time when households are seeing energy prices rise faster than inflation, the tactic could have widespread political appeal, she noted.

NESCAUM plans to check back in with states and report out on their progress each year, Levin said. “The cool thing about our work is that we bring states together to learn from one another,” she added. “Part of making this transition happen more rapidly is lifting up the things that are really working well.”