DALLAS — Past gnarly live oaks, behind a barbecue joint and a brewery in a suburb north of Dallas, a white-washed brick commercial building extruded its own wispy cloud into the Texas sunlight.

Inside, the startup Skyven Technologies was running a mechanical apparatus dubbed Arcturus, which turns waste heat into industrial-grade steam. It’s so new that I was the first outsider to see the contraption up close — signing my name in slot No. 1 in the log book. But, soon, Skyven will show it off to manufacturers who want to save money on energy bills while cutting their carbon emissions.

Industrial heat causes about 20% of global carbon emissions, per a McKinsey analysis. Very high-temperature processes, like melting ores for steelmaking, are tough to replicate without fossil fuels. But, in Skyven’s analysis, about half of those industrial heat emissions come from making steam, usually in boilers that burn gas or other fuels. Skyven, and a growing cadre of startups, are designing clean, electric, hyper-efficient heat pumps to take over that task.

They have their work cut out for them: Right now, the U.S. is home to about 39,000 industrial boilers, according to Richard Hart, a decarbonization expert at the think tank American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. The steam they generate is used to sterilize injectable drugs, turn pulp into paper, pasteurize milk, cure lumber, and more.

Boilers are reliable and not particularly expensive — and in the U.S., natural gas is cheap — so it’s hard for cleaner alternatives to compete. ACEEE, which tracks announcements of new industrial clean-heat projects, namely heat pumps or thermal batteries, currently registers just 19 completed installations nationwide.

Skyven tackles the tricky economics by focusing on energy savings. The startup installs Arcturus at no cost to the customer, alongside existing gas boilers. The heat pump taps into the factory’s waste heat, which helps it reach high temperatures with far more efficiency than older technologies. Skyven and the customer split the savings from making cheaper electric steam, but if electricity prices spike, Skyven temporarily switches back to the gas boiler to avoid higher costs.

“What we want to do as a business is make industrial manufacturing in the U.S. and worldwide a lot more efficient, by being the leader in upcycling industrial heat and reusing it without having to create it anew,” Skyven founder and CEO Arun Gupta told me.

For now, the steam produced in Skyven’s site near Dallas floats harmlessly into the sky. But with contracts signed and real-world data to share, Skyven is mobilizing for a wave of factory deployments in the years to come.

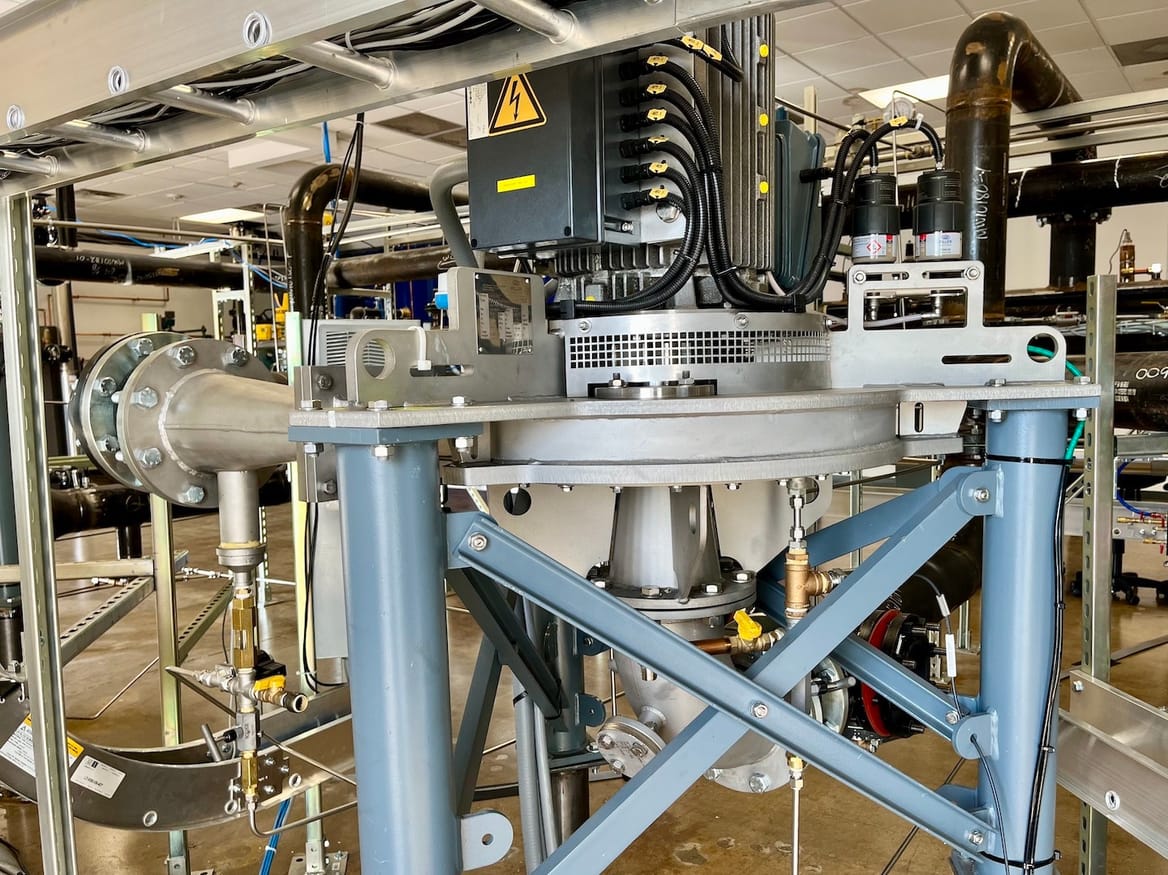

Arcturus is not something you can pull out of a box fully formed, but a room-sized network of interlocking pipes, chambers, and appliances.

Gupta and Jim Saccone, Skyven’s senior vice president of global sales, handed me earplugs and led me into the clamorous, sun-washed room where the machinery whirred. In one corner sat a conventional gas boiler and a water heater, which acts as a stand-in for the waste source Arcturus will harness in factories.

Arcturus uses a heat exchanger to transfer energy from whatever the source is to a loop of water. While I observed it, relatively cool water from Arcturus hit the heat exchanger and rose from around 67˚C (153˚F) to 92˚C (198˚F). That heated water flows through shiny steel piping into a thick metal vacuum chamber, which lowers the boiling point and swiftly “flashes” the water into steam.

That low-pressure steam then travels through a series of four compressors, all noisily spinning at roughly 15,000 revolutions per minute. Each compressor ratchets up the temperature and pressure of the steam until it hits the target zone, which can be tailored to the needs of each factory.

“Because we make this steam with waste heat that was otherwise going to get dumped, and then just use compressors to compress that steam, that’s much less energy than using the energy to make the steam but not having any compressors,” Gupta said.

The demonstration unit generates 105˚C (221˚F) steam, which runs back through a pipe into the “customer” side of the room. In a real customer setting, Arcturus could sit up to half a mile from the factory where it delivers steam, if space is limited. For now, the vapor just vents through the roof.

The demo system produces up to 1 megawatt of thermal output. Skyven has already signed deals in the 10- to 15-megawatt-thermal range — these will have a similar footprint, Gupta said, but use bigger pipes and compressors. The technology can heat steam all the way to 215˚C (419˚F) if needed; that’s unusually high for industrial heat pumps, which typically reach around 170˚C (338˚F).

Since Skyven is producing real heat now, it has established an empirical baseline for its operating efficiency. The term of art here is “coefficient of performance,” which measures how much energy is produced per unit of energy consumed.

Gas boilers score 0.83, Saccone said, losing some energy along the way. Electric resistance boilers, a commercially mature electric heat technology, hit close to 1, a near-complete transfer of energy into heat. Startup AtmosZero recently installed an air-source industrial heat pump at New Belgium Brewing in Colorado that can reach 165˚C (329˚F); that device sports a COP of around 2.

Skyven’s average measured COP for its pilot is 6.5, but Gupta said he aims to raise it to 8 within the next three months. This isn’t a fixed value: It depends on factors like how hot the waste source is and how hot the steam needs to get. The demo site nonetheless establishes a real-world high water mark of how efficient Arcturus can be.

“The higher that [COP] value goes, the less important the spark gap is going to turn out to be,” said Hart, referring to the gap between power and gas prices. If, for example, a unit of electricity costs twice the equivalent in gas, but produces six or eight times the heat, then the heat pump is cheaper to run than a gas boiler.

Gupta didn’t set out to invent an industrial heat pump.

He had been working at Texas Instruments’ digital-light-projection business, designing the chips that run most every digital movie-theater projector. He wanted to do something good for the world and was concerned about climate change. “So, I was skimming ARPA-E research papers, as one does,” Gupta recalled, as we noshed on burgers up the road from Skyven headquarters.

The Department of Energy’s ARPA-E funds research on potentially transformative technologies. That archive was where he hit on the challenge of clean industrial heat; he figured, with his expertise manipulating light, he could make a better solar-powered heat source.

Gupta founded Skyven in 2013. At first he just tinkered in his Dallas garage, for a while confined to a wheelchair by a calamitous motorcycle accident. Eventually, he moved to the Dallas Makerspace and raised pre-seed financing for his concept. But the sheer amount of insulated plumbing needed to distribute the solar thermal heat wrecked his project economics.

“I made the mistake of a classic technical founder, in that I had a technology that I thought solved the market problem, but I didn’t really validate the market problem,” he explained. Still, he didn’t want to give up on his goal.

“At the time, no one knew anything about industrial heat,” Gupta said. The cleantech industry had spawned plenty of companies that could sell solar electricity to commercial customers, but hardly any solutions for heating needs at factories.

So Skyven reoriented around developing and financing energy-efficient upgrades for industrial heat using the best available technologies. The startup raised seed funding for this tech-agnostic model and landed a breakthrough deal with California Dairies, Inc., the largest dairy co-op in the Golden State.

The mission was to reduce gas combustion, saving money and carbon emissions, at major dairies in Turlock and Visalia. Skyven did this by deploying three types of equipment at each site: solar thermal to generate clean heat, smart steam traps to monitor steam loss in the existing system, and apparatuses to recover heat from boilers.

Skyven bundled $9 million in grants from the California Energy Commission with utility incentives from Pacific Gas & Electric and Southern California Gas Co., and landed project financing from Kyotherm, a French lender for clean-heat projects. With that combined funding, Skyven installed the equipment at no up-front cost to the dairies, and then as the facilities reduced their gas consumption, split the cost savings with them. The dairies could see a metered readout of the avoided gas combustion, and they paid Skyven an agreed-upon portion of it.

Installation wrapped up in 2023. The interventions, still operating under 10-year service contracts, are cutting 7,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide annually by avoiding over 110,000 million British thermal units of natural-gas combustion, more than originally anticipated. But Skyven concluded that the commercially available solar thermal panels weren’t a competitive source for heat, reporting to the California Energy Commission that a steam-generating heat pump would be “a more effective decarbonization solution with a wider appeal.”

Around that time, Gupta said, Skyven was scoping out a deal for an ethanol company in the Midwest. The team came across a bare-bones case study from a European ethanol plant that had built something called an “open cycle mechanical vapor recompression” device — machinery that takes waste heat, compresses and heats it, then recirculates it into the plant.

The problem was, outside of that European plant’s in-house engineering team, “there’s really no one in the world that knows how to implement this,” Gupta said. Skyven tried hiring a third-party engineering firm to draw up designs for the Midwestern customer, but that proved unsatisfactory. “We then said, ‘Okay, what if we built that experience and expertise and essentially invented this system in house?’”

Having learned from his early missteps, Gupta first vetted the idea with a slew of potential customers, who responded enthusiastically. Then Skyven stopped its tech-agnostic deals and staffed up on engineers, drawing on millions of dollars of revenue from the dairy projects. The company’s task, Gupta said, was to take existing steam compressors and adapt them into a heat pump that can be easily inserted into “an actual manufacturing facility with all the intricacies and challenges.”

Now that process has concluded, as evidenced by the steam billowing into the blue Texas sky. And Skyven did all that having raised just $11 million in outside investment and having generated real revenues, quite the outlier for Silicon Valley-backed cleantech.

A functional, highly efficient industrial heat pump is just table stakes. For Skyven to succeed, it must fight an uphill battle convincing big, old companies to bet on new technology. That’s why the startup designed its product and deal structure to minimize risk for the customer.

Arcturus can be assembled without interrupting factory operations, so customers don’t have to sacrifice production time to get the benefits of clean heat. Then Skyven schedules the steam and water connections to coincide with the plant’s regular maintenance shutdown. If that’s not possible, workers can perform a “hot tie-in” to connect Arcturus without stopping factory operations.

Skyven only runs the heat pump when it’s less expensive than using the legacy heat source. This entails real-time algorithmic calculations based on the price of electricity, the price of gas, and the COP. Company software toggles back to the original gas boiler in moments when power prices surge; if Arcturus is running, it’s got to be saving money compared to burning gas, with a target of at least a 30% reduction in cost.

This arrangement means that factories don’t have to pony up millions of dollars up front to decarbonize their heat.

“You can spend your dollars on stuff that’s core, like expanding production or improving quality or rolling out a new product line, and you can still hit your sustainability goals,” Gupta said.

Facilities teams that partner with Skyven can even tell their bosses that they’ll reduce their future operating budgets through the savings from electric heat, Saccone said.

Skyven is able to offer no-money-down steam with the ongoing financial support of Kyotherm, which financed the waste-heat collectors Skyven put into the two California dairies. Now, Kyotherm has signed an agreement whereby Skyven pitches Arcturus installations, and Kyotherm agrees to finance ones that clear its performance thresholds.

“You cannot give a blank check; you need to look at each different project,” said Remi Cuer, Kyotherm’s investment and business development director.

Kyotherm expects high single-digit internal rates of return; that’s more than solar or wind farms would pay, because emerging heat tech carries more risk. But assuming Skyven keeps bringing attractive projects, it can expect project financing for quite some time. Cuer declined to name a specific cap on the agreement but suggested his firm could fund a few hundred million dollars of Skyven installations.

Financiers usually run away from new technology until several of their peers have vetted it. But Kyotherm wasn’t afraid to back Skyven despite the newness of Arcturus. Cuer attributed that assurance to having seen how the team worked on the dairy installations. The Dallas-area pilot project is “really important for us,” he added, so his team can review the logs of COP, uptime, and other key metrics.

“It’s a market, heat pumps, where there are a lot of [original equipment manufacturers] and perhaps, currently, not enough project developers,” Cuer mused.

Until a few months ago, Skyven had a surefire tool for getting its first customer-oriented Arcturus installations done: It had won $145 million from the DOE, part of a $6 billion Biden-era effort to decarbonize heavy industry.

The Trump administration canceled Skyven’s fully contracted grants along with many others in a legally dubious effort to roll back binding federal commitments for clean energy.

“The loss of certainty on the $6 billion from the DOE’s Industrial Demonstrations Program is a challenge for the recipients. They are all considering next steps,” Hart said. But even where the money is gone, the knowledge and corporate buy-in required to win those grants lives on. The grantees “had to really think about how to do this technically, how to bring the right partners together, get the plants excited about the idea, and do all of that due diligence as part of their submissions,” Hart said.

Most other companies losing those grants boast far greater balance sheets, like Kraft Heinz and Diageo. Skyven, a much smaller company, is pursuing an internal appeal within DOE, and not currently seeking legal recourse, Gupta said.

“The cancellation of the funds has not killed the projects,” Gupta said. “They are actually all still moving forward, they’re just moving forward a lot slower.”

The plan had been to build a slew of them and learn from the results to drive costs down. Instead, Skyven slowrolled development to grind out system-cost reductions, so the projects would still make financial sense without government support. This effort went surprisingly well, Gupta reported, and pushed costs 40% lower in just a few months.

Skyven once again has had to zig and zag, improbably emerging stronger from the turbulence.