Home-electrification startup Jetson just raised $50 million to fuel its ambitious effort to slash the cost of installing heat pumps in the U.S. and Canada.

Founded in 2024, Jetson says it can install the ultraefficient appliance for 30% to 50% less than competitors. The company has also developed its own smart heat pump, called the Jetson Air, which it unveiled last September. Currently, the startup operates in its home base of British Columbia, Canada, and in Colorado, Massachusetts, and New York, with over 1,000 heat-pump installations to date.

Jetson’s team, which has grown from 75 employees in September to 120 today, has extensive experience in designing consumer hardware. Co-founder and CEO Stephen Lake previously led smart-glasses startup North, which Google acquired in 2020. Several former North employees have joined Lake to work on home-electrification products.

The infusion of Series A funding will help Jetson continue to grow its team — and its market reach.

Jetson will use the investment to develop other home appliances, find ways to further reduce costs for consumers, and expand into new geographies, Lake said. The company plans to unveil a heat-pump water heater midyear.

As for geographic expansion, Jetson will prioritize regions where “the need for efficient heating is clear,” he said. “We’ll be in Washington state shortly and will be announcing new locations throughout the year.”

Funders flocked to the company in part because Jetson is pursuing “an absolutely massive market,” according to Ryan Gibson, an investor at Eclipse Ventures, which led the funding round. Roughly half the homes across the U.S. and Canada burn fossil fuels for heating, according to government data, and could switch to emissions-free heat pumps.

The market for the heating-and-cooling appliance is ripe for disruption, according to Gibson. The way that heat pumps are traditionally sold and installed is fragmented and low-tech, with little pricing transparency, he said. Contractors typically need to perform assessments in person in order to provide an estimate. By contrast, Jetson provides instant quotes online and at competitive prices that rival the cost of a furnace plus a conventional air conditioner.

On average, a Jetson system costs about $15,000 before local incentives, Lake said. That’s quite a departure from the national average. Using 2024 data, nonprofit Rewiring America estimated that for a medium-size home, a central heat-pump system costs a median of $25,000. (Jetson declined to share whether it’s currently profitable.)

To achieve those lower prices, Jetson takes a vertically integrated approach: from designing its software-enabled and sensor-equipped heat pump to having its own technicians roll up in one of the startup’s green electric trucks to install the appliance in a person’s home. The company also provides ongoing remote monitoring so that it can alert customers to quiet issues, like a dirty air filter that’s eroding performance.

In addition to Jetson, venture capitalists have backed a few other “heat-pump concierge” startups in recent years, though more modestly. Elephant Energy raised $3.5 million in seed funding in 2022; Tetra secured $10.5 million in seed money in 2023; and Quilt, which makes mini-split systems, added to a $33 million Series A with a $20 million Series B round in December.

Jetson’s funding round comes just after the U.S. government repealed a $2,000 tax credit for heat pumps, as well as subsidies for other efficiency upgrades, and as the nation struggles with rising energy bills. This presents a clear opportunity for firms like Jetson, which promise big cost savings over traditional installers. And with the new cash, the startup has a chance to deliver.

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the Week” column.

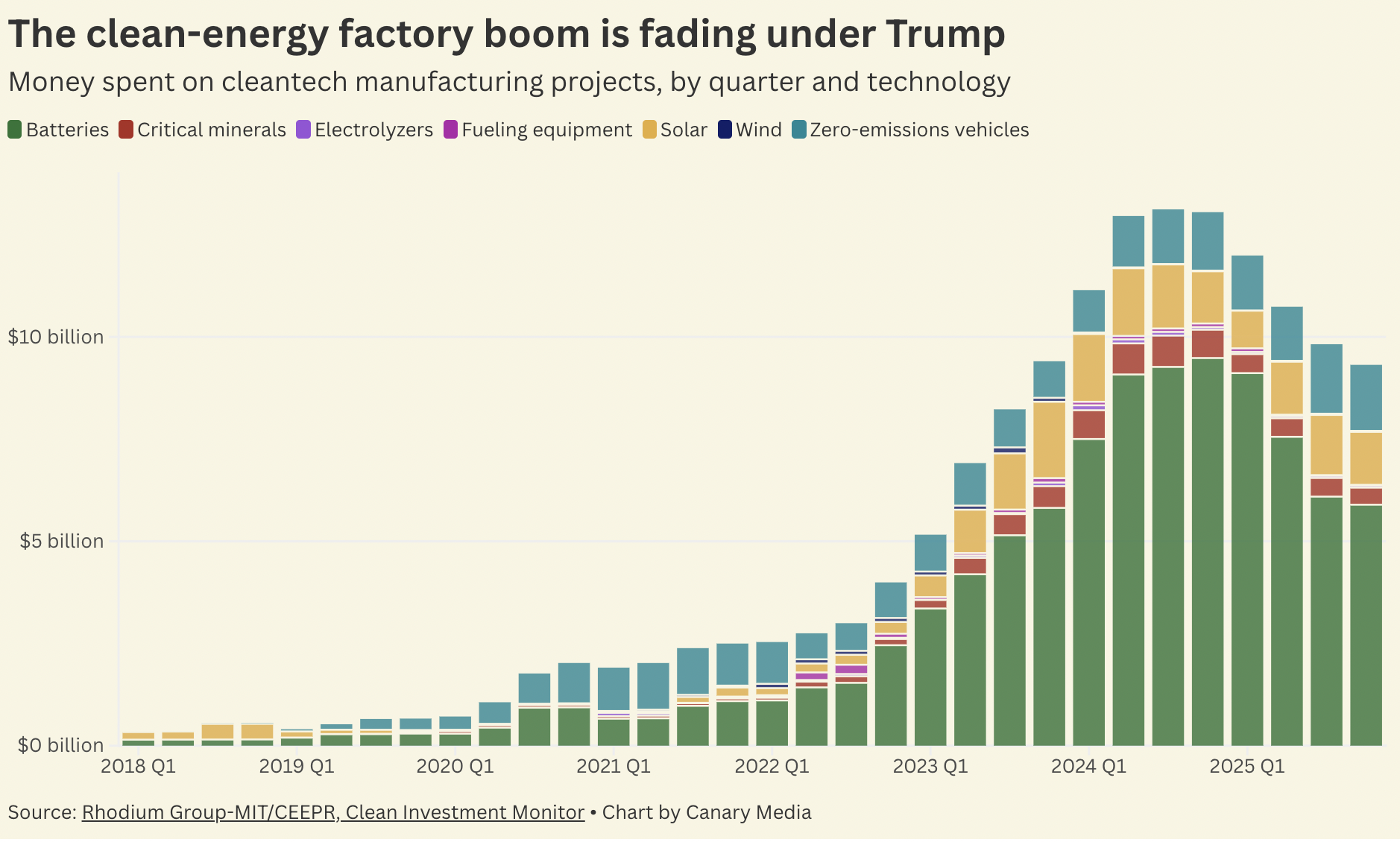

Clean energy manufacturing was on the upswing in the U.S. Then the first year of Trump 2.0 happened.

After years of increasing investment in factories to make batteries, electric vehicles, solar panels, and more — a surge prompted by the Inflation Reduction Act — the trend reversed under the Trump administration last year. Companies spent a total of $41.9 billion on cleantech manufacturing facilities in 2025, down from $50.3 billion the year before, per fresh figures from the Clean Investment Monitor, a joint project from Rhodium Group and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research.

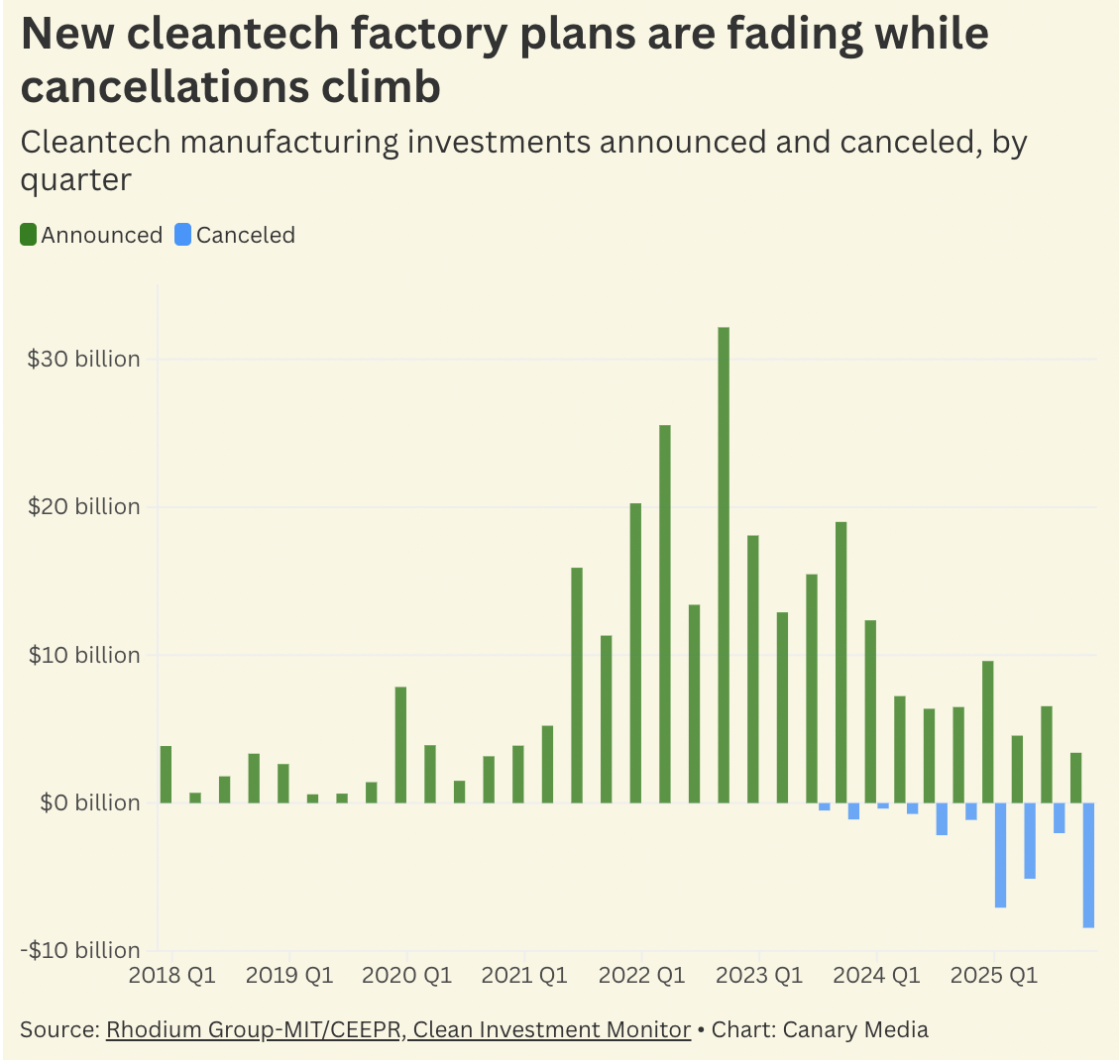

More concerning, however, is the fact that businesses are making fewer new plans to invest in cleantech factories — and a whole lot of companies are backing out of prior commitments.

Cancellations nearly matched factory announcements last year: Firms unveiled a total of $24.1 billion in new cleantech manufacturing projects, but scrapped $22.7 billion worth.

It’s a dramatic reversal. The Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act had spurred well over $100 billion in cleantech manufacturing commitments through incentives for both factories and their customers, be they families in the market for an EV or energy developers building a solar megaproject. The ensuing boom in cleantech factory construction created thousands of jobs and caused overall manufacturing investment to soar. Most of the investment was planned for areas represented by Republicans in Congress.

But last year, the Trump administration put strict stipulations on incentives for factories and repealed many of the tax credits that helped generate demand for American-made cleantech. It also showed an astonishing hostility to clean energy projects — namely offshore wind — and cast a general cloak of uncertainty over the entire economy.

To be fair, other potential factors are at play.

Some of the slowdown in cleantech factory investment could simply be the market maturing. Plenty of projects announced right after the Inflation Reduction Act might already be online, or close to it. Or it could be the result of the gravitational pull of the data center boom, which is attracting gobsmacking amounts of capital that could have otherwise financed more cleantech factories.

But either way, as the new data shows, the Trump administration has weakened the case for investing in expensive projects tied to clean energy. I’m willing to bet that the consequence will be more factory cancellations — and less investment — over this year, too.

This analysis and news roundup come from the Canary Media Weekly newsletter. Sign up to get it every Friday.

When it comes to state politics, 2026 is already in full swing. As legislators reconvene and new governors are sworn in, it’s becoming clear that leaders will focus on one energy issue in particular this year: affordability.

While last year’s elections didn’t bring any major changes to the White House or Congress, skyrocketing energy prices played an undeniable role in propelling Democrats to victory in state elections across the country.

Take a look at New Jersey, where Democratic Gov. Mikie Sherrill was sworn in this week after campaigning on a promise to lower power prices while building out clean energy. She took her first steps in that direction on Tuesday, signing executive orders to accelerate solar and storage development, consider freezing electricity rate hikes, and expand utility bill credits for customers.

Those credits will be funded in part by the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, an East Coast carbon market that saw good news with the inauguration of Virginia Democratic Gov. Abigail Spanberger this past weekend. Spanberger is already moving to rejoin RGGI, with an assist from the state’s Democratic-controlled legislature, after the previous Republican governor pulled Virginia out of the program back in 2023. On her first day in office, Spanberger also directed state agencies to find ways to curb energy and other household costs.

Affordability is sure to continue to dominate politics this year in Virginia, also known as the data center capital of the world, clean energy advocates recently told Canary Media’s Elizabeth Ouzts.

“Oftentimes, I go into a legislative session sort of just guessing what people are going to care about,” said Kendl Kobbervig of Clean Virginia. Not this year.“No. 1 is affordability, and second is data center reform.”

Massachusetts’ legislature shares that priority, reports Canary Media’s Sarah Shemkus. But even though the statehouse remains firmly in Democratic hands, lawmakers aren’t aligned on how to curb costs in the long term. Some are targeting volatile natural gas prices and the cost of replacing aging pipelines, others say clean energy and transmission construction are to blame, and still others are homing in on utility profit margins.

The reality is that the energy affordability crisis isn’t a problem with just electricity prices or natural gas prices; both are rising at rates higher than inflation across the country. And so it’s going to take strong, and perhaps creative, solutions to keep them in check.

Trump’s year of energy upheaval

It’s been a year since President Donald Trump took office for the second time, and there’s been no shortage of energy-industry shake-ups in the months since.

On his first day in office, Trump called out rising power demand and declared a national emergency on energy, which he has since used to justify keeping aging coal plants open long past their retirement dates.

His signature spending law, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, gutted tons of clean energy tax incentives. And that’s not to mention the administration’s decarbonization funding clawbacks, its holdup of renewables permitting, and its relentless attacks on the nation’s offshore wind industry.

Trump’s year-two agenda is already starting to take shape. Expect to see his administration order more coal plants to stay open, cancel additional clean energy funding, and throw up hurdles we can’t even imagine yet.

Geothermal is having a moment

As clean energy sources like offshore wind and solar struggle to snag a foothold in the new, post–tax credit world, geothermal proved this week that it still has the juice.

A wave of announcements from pioneering geothermal startups began on Wednesday, with Zanskar announcing it had raised $115 million in a Series C funding round. It’ll use the infusion to expand its AI software, which it used to uncover an untapped, invisible geothermal system in Nevada last year. Also on Wednesday, Sage Geosystems announced a more than $97 million Series B round, which will fund its first commercial-scale power generation project, slated to come online this year.

Fervo Energy completed the trifecta as it quietly filed for an IPO, Axios Pro reported on Thursday. The company hasn’t shared details about the filing, but said in December that it had raised about $1.5 billion so far in its quest to build a massive enhanced geothermal system in Utah.

Back to work: Wind farms off the coasts of New York, Rhode Island, and Virginia have all restarted construction after legal wins last week against the Trump administration’s stop-work order, though two other projects remain paused. (Canary Media)

Solar keeps surging: An Energy Information Administration analysis finds utility-scale solar is the fastest-growing power generation source in the U.S., and will continue to expand through 2027 as the shares of coal and gas in the energy mix decline. (EIA)

Rural resilience: North Carolina towns devastated by 2024’s Hurricane Helene are installing solar panels and batteries at community hubs to prepare for future disasters, with help from a program that could become a national model. (Canary Media)

Clean-steel influencers: A new report shows automakers buy at least 60% of the primary steel made in the U.S., which gives them leverage to push steelmakers to clean up production. (Canary Media)

Batteries at breakfast: A Brooklyn bagel shop is cutting its power bills by using suitcase-size batteries to run its oven and fridges when electricity demand is high. (Canary Media)

Renewables’ European win: Wind and solar generated 30% of the EU’s electricity last year, while fossil fuels provided 29%, marking the first time renewables have beaten coal, oil, and gas. (The Guardian)

Clawback consequences: Some communities that lost federal climate grants last year have sued to reclaim them, while others have had to move on from projects that would’ve helped them curb pollution and adverse health effects. (Grist)

A leading data center developer and a pioneering Texas battery owner have formed a mutually beneficial partnership that models a new way for energy storage to accelerate the AI infrastructure build-out.

Storage firm Eolian completed the Chisholm Grid battery in 2021, placing 100 megawatts/125 megawatt-hours of capacity next to a substation 7 miles northwest of downtown Fort Worth. The site was able to discharge its full capacity for just over an hour — a design that worked well for the first wave of big Texas grid battery projects, which could make good money by providing rapid-response ancillary services.

Another 15 gigawatts of storage have piled into Texas since then, and revenues from those once-lucrative ancillary services have plummeted given the glut of batteries. Meanwhile, the market managed by the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, or ERCOT, is changing in other ways that reward longer-duration batteries.

So Eolian CEO Aaron Zubaty came up with a plan to meet the moment. “We’ve already taken the battery storage site offline so that we can upgrade the facilities and ultimately expand the usable duration,” Zubaty said. But he added, “Even though the battery is offline, the site is proving that well-placed infrastructure can create ongoing value across multiple use cases.”

That’s right, Zubaty found a way to get paid for not using a battery: by temporarily lending the site’s grid connection to data center developer CyrusOne. The Dallas-based company runs 55 data centers around the world and is currently building 10 more, including one next door to Chisholm. That data center, dubbed DFW7, could come online later this year.

“Getting a new connection to the grid at the scale of this site, more than 100 megawatts, that’s generally a multiyear process,” CyrusOne CEO Eric Schwartz told Canary Media.

But in this case, he noted, CyrusOne will activate its data center campus one to two years earlier by using Eolian’s grid interconnection while that firm renovates its battery plant.

“Time to market matters, but also certainty,” Schwartz said. At Chisholm, “the grid infrastructure is there and ready to go.”

The power sector has become consumed with the question of how to meet the AI industry’s rapidly ballooning electricity needs. One common assumption is that new gas plants will pave the way for the AI revolution, but gas turbines face yearslong backlogs that defy the “speed to power” desired by AI companies. Ask any battery developer today and they’ll tell you they have booming business prospects with data center customers, but hardly any of these have been made public, aside from a deal between energy storage specialist Calibrant and Aligned Data Centers in Oregon, and now the new Eolian–CyrusOne agreement.

This arrangement emerged from discussions in 2023, and CyrusOne broke ground last April. If construction goes to plan, the rebuild of the battery will wrap up around the time that wires utility Oncor finishes its grid upgrades for CyrusOne to get its own hookup. Then Eolian can get back to bidding into ERCOT, with a duration long enough to qualify for the forthcoming Dispatch Reliability Reserve Service, which requires power plants to discharge for at least four hours.

Chisholm runs on Samsung battery cells with the nickel-manganese-cobalt chemistry, and they have sustained very little degradation over five years of service, Zubaty said. The initial plan is to keep those original cells but restructure them: By dropping the capacity to 25 megawatts, Eolian can lengthen the discharge duration to the five-hour mark. Then it can add in new batteries to fill up the remaining space; the site can hold up to 250 megawatts, based on its grid-connection agreement.

It’s not yet clear if this deal will start a new trend or constitute a fruitful anomaly. There are only so many batteries in need of repowering in places eyed by data center developers. If storage developers get too comfortable leasing out their grid connections, they’ll reduce themselves to glorified landlords. But it says something about the interplay between data center development and battery storage, and how the two could work together to make the electricity network more nimble.

Texas generates tens of gigawatts of solar and wind power far from its cities, then has to send that electricity to consumers, which can cause congestion on transmission wires. Years before the Texas storage boom or the recent AI phenomenon, Eolian looked for areas where batteries could improve utilization of the transmission grid by arbitraging electricity between times of plenty and times of scarcity.

“Our primary strategy for developing battery storage sites in 2016 and 2017 was to start ringing every major city we could with queue positions in locations that were likely future transmission constraints or that were a bridge between load growth and far-flung generating resources,” Zubaty said.

CyrusOne also wanted to be near the population center. Some of its customers benefit from running their computation closer to users. And CyrusOne itself sees a major benefit in building near Fort Worth’s population of skilled technicians, both for construction and ongoing operations, Schwartz said. The city’s authorities have also been supportive of data center construction, as has Texas more broadly.

On top of that, CyrusOne was attracted to the same high-capacity power infrastructure that lured Eolian to that node on the grid years ago. Those heavy-duty wires, and what Zubaty called “an epic substation,” make this a good place to charge a battery or power a huge data center without having to do too much upgrading.

“Five to 10 years ago, we would’ve located the site based on other criteria … and worked with the utility to bring power to the site,” Schwartz said. “Now, we’re bringing data centers to the power rather than trying to bring the power to the data centers.”

Other early entrants into the ERCOT battery market face the same pressures that Eolian responded to, and if they decide to repower their batteries, more data center developers could pursue similar opportunities to come online faster. Admittedly, the geography and timing for such a solution have to line up just right, but these partnerships could prove a critical stepping stone in the headlong rush to build computing infrastructure.

Offshore wind developers are back to building three major U.S. projects nearly a month after the Trump administration ordered them to pause construction.

Ørsted, Equinor, and Dominion Energy all got the green light from federal judges last week to resume work on their massive, multibillion-dollar wind farms off America’s east coast. The companies wasted no time restarting the installation of turbines, offshore substations, and other equipment — eager to make up for delays that had cost each of them millions of dollars a day and threatened to tank at least one project that is more than halfway complete.

The developers had been stuck in limbo since receiving the Dec. 22 suspension order from the U.S. Interior Department, which cited unspecified “reasons of national security” — a rationale that failed to convince federal judges as they weighed developers’ requests for relief. Two other in-progress projects remain mired by delays as they await hearings.

The late-December order was the culmination of the Trump administration’s yearlong assault on offshore wind, which has managed to freeze new development but has been less successful in stopping projects already underway. Most of the five projects are in advanced stages of construction and viewed as critical by grid planners for keeping electricity reliable and affordable. These offshore wind farms are likely the only ones that will get built nationwide in the coming years because of Trump’s interventions.

Dominion Energy, which is developing the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project, said it delivered the first batch of turbine components by ship to its leasing area off Virginia Beach, Virginia, last weekend and is now installing the first of its 176 turbines. All the turbine foundations are already in place for the $11.2 billion project, and the utility is working to start producing power in the first quarter of this year.

The wind farm is expected to supply 2.6 gigawatts of clean electricity to the grid when fully completed later this year — power that the region can’t afford to lose, according to the mid-Atlantic grid operator PJM Interconnection.

In a Jan. 13 court brief supporting Dominion Energy, PJM said the offshore wind project would help with the “acute need for new power generation to meet demand” in the 13-state region, much of which is being driven by the boom in AI data centers. “Further delay of the project will cause irreparable harm to the 67 million residents of this region that depend on continued reliable delivery of electricity,” according to PJM’s filing.

Meanwhile, off the coast of Rhode Island, Ørsted has resumed construction on the 704-megawatt Revolution Wind project, which was nearly 90% complete when the federal stop-work order came late last month. The Danish energy giant was hit with a similar order in August, which a federal judge lifted in September given the lack of any “factual findings” by the Trump administration.

Of Revolution Wind’s 65 wind turbines, 58 are already in place, as are the cables and substations needed to bring the power to shore. At the time of the December suspension, the $6.2 billion project had been expected to start generating power as soon as this month, according to Ørsted.

Equinor, which had also previously received a separate stop-work order, is back to work on its 810-MW Empire Wind project off the coast of Long Island, New York.

The developer recently warned that the $5 billion project, which is more than 60% complete, would likely face cancellation if work couldn’t resume by Jan. 16; it won a favorable ruling on Jan. 15. Molly Morris, president of Equinor Renewables America, said the project is using a heavy-lift vessel that is available at the project site only until February, The City reported. After that, Equinor wouldn’t have been able to lease the vessel for another year, creating untenable project delays.

A spokesperson for Equinor said the company now expects to complete work assigned to the vessel, which includes installing an offshore substation, following the injunction ruling.

Continuing construction on America’s offshore wind farms “is good news for stressed power grids on the East Coast,” Hillary Bright, executive director of the advocacy group Turn Forward, said in a statement last week. She added that if projects aren’t allowed to advance, the electricity system in the heavily populated region will be “more likely to experience reliability issues and see ratepayer bills soar.”

Americans’ utility bills are already climbing nationwide, owing in large part to the rising prices and constrained supplies of fossil gas. Residents in colder-climate states are especially feeling the squeeze this winter — though early data shows that existing offshore wind operations are helping reduce electricity costs in some places.

Vineyard Wind, a 800-MW wind farm off the coast of Massachusetts, has been sending power to the grid from 30 of its planned 62 turbines since last October. On Dec. 7, an especially chilly day, the project’s wind output helped displace a significant amount of fossil gas on the wholesale market, resulting in savings of more than $2 million for New England ratepayers over the course of the day, Amanda Barker, the clean energy program manager with Green Energy Consumers Alliance, said on a Jan. 21 press call.

Vineyard Wind is one of the two projects waiting to resume construction in the wake of Interior’s December suspension order. Its developers, Avangrid and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, sued the federal government on Jan. 15, becoming the last of the affected firms to seek legal relief from the Trump administration’s attacks. Vineyard Wind is now 95% complete, with all but one of its turbines now hovering over the Atlantic Ocean.

The second stalled project, Sunrise Wind, is an Ørsted development off the coast of New York. The 924-MW wind farm is almost 50% complete and, before the stop-work order, was expected to come online in 2026. A court hearing for the development is scheduled for Feb. 2, and the delay is costing Ørsted millions of dollars in the meantime.

Overall, the court orders from last week represent a win for getting more electricity onto the grid during a time of rising demand — and another round of setbacks for Trump’s efforts to destroy the fledgling sector.

Still, it’s hard to say whether this marks the administration’s final attempt to stymie projects or whether more delay tactics are coming for America’s beleaguered offshore wind projects.

Primary steel, the strongest and most durable form of the metal, is typically also the dirtiest kind. That’s because the most common way to forge it begins with producing iron in coal-fired blast furnaces.

Now, for the first time, a new report identifies who buys the lion’s share of primary steel in the United States — and how much steel they’re buying.

At least 60% of U.S. primary steel is purchased by automobile manufacturers, according to an analysis from the environmental group Mighty Earth that was shared exclusively with Canary Media. The six automakers identified in the report — Ford Motor Co., General Motors Co., Honda Motor Co., Hyundai Motor Group, Stellantis, and Toyota Motor Corp. — produce 73% of all new cars on American roads.

The finding highlights a point of leverage for customers in decarbonizing American steel production at a moment when steelmakers are largely reversing plans for greener mills and doubling down on coal-fired blast furnaces.

“The auto market drives blast furnaces in the U.S.,” said Matthew Groch, senior director of decarbonization at Mighty Earth. “If they really cared and wanted to, they could put pressure on these companies they’re buying steel from. But they aren’t, and they don’t.”

Only one of the six automakers, Honda, responded to emailed questions from Canary Media. But the Japanese firm declined to comment on its steel suppliers.

“Honda is actively working to reduce CO₂ emissions associated with raw material procurement and manufacturing processes,” Honda spokesperson Chris Abbruzzese said in an email. “We do not publicly disclose individual supplier relationships.”

Automakers have traditionally relied on primary steel to form the outer shell of their cars because it’s long been considered higher quality than steel made from recycled scrap metal in electric arc furnaces. Increasingly, though, thanks to improvements in its purity and strength, so-called secondary steel has been able to displace some of that demand. Steel recyclers like Nucor say the auto sector represents a growing share of their customer base, but primary steel made using coal still dominates the sector.

To identify the buyers of primary U.S. steel, Mighty Earth commissioned the consultancy Empower LLC to conduct “an exhaustive review” of supply chains, according to the report. The analysts then reviewed “everything from annual reports and investor presentations to new articles and company websites, looking for clues regarding links between the steel facilities of interest and their ties to the largest U.S. automakers.” The study relied on supply chain and financial data from the platforms Panjiva, Sayari Graph, S&P Capital IQ, and MarkLines, and it used OpenRailwayMap to track materials shipped by train.

Since President Donald Trump returned to office a year ago, the nascent efforts to clean up America’s primary steel production have largely collapsed.

Cleveland-Cliffs, which had been awarded a $500 million grant from the Biden administration to finance construction of new, greener equipment at one of its Ohio steelworks, abandoned the initiative and is now working with Trump’s Energy Department to develop a coal-focused scope for the project.

U.S. Steel, whose sale to Japanese rival Nippon Steel was approved by the Trump administration, finds itself at a crossroads. The company has promised some greener investments in the U.S. but has yet to announce any specifics. Its new owner, however, has a reputation as “a coal company that also makes steel” — and Nippon has also promised to invest in upgrading U.S. Steel’s blast furnaces to last longer.

That leaves Hyundai’s project to build a low-carbon steel factory in Louisiana as the flagship push for clean steel in the U.S.

Despite recent challenges from the Trump administration, Hyundai has signaled its commitment to bringing the facility online by 2029. The plant is designed to first use blue hydrogen, the version of the fuel made with fossil gas and carbon capture equipment, to produce the cleaner direct reduced iron. But by the mid-2030s, the facility is expected to switch to green hydrogen, made with electrolyzers powered by renewables.

The low-carbon iron will then be fed into electric arc furnaces to produce steel — making it the first integrated low-carbon steel plant in the U.S. That Louisiana plant could reduce emissions by at least 75% relative to a traditional integrated steel plant with a blast furnace and basic oxygen furnace.

In a sign of progress, Hyundai this month announced plans to test its DRI equipment at an existing steelworks in South Korea in anticipation of bringing the technology to Louisiana.

Once that Louisiana plant comes online, Groch said, it’s expected to generate enough steel to meet Hyundai’s needs and supply additional potential buyers — opening up an opportunity for other automakers. In its report, Mighty Earth calls on automakers to commit to buying more green steel in the coming years.

General Motors and Ford have committed to buying at least 10% green steel by 2030 as part of a pledge via the First Movers Coalition, led by the World Economic Forum. Other global carmakers not included in Mighty Earth’s report, such as Volvo, Mercedes-Benz, and BMW, have adopted separate targets. Honda, Stellantis, and Toyota, meanwhile, have avoided making such promises.

Holding car companies to those targets has proved challenging. While some companies have vowed to slash emissions by buying more low-carbon steel, a September 2024 report by the International Council on Clean Transportation found that carmakers’ pledges to buy fossil-free steel by 2030 cover less than 2% of their total demand for the metal.

“We’re not asking for everyone to have 100% green steel,” Groch said. “But these are their commitments, and the car companies are the ones driving investment in steel.”

The startup Fervo Energy has reportedly filed for an IPO to help fund its build-out of next-generation geothermal projects.

Nearly a year after first floating the idea, the Houston-based Fervo submitted a confidential S-1 filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Axios Pro reported on Thursday. The startup has raised about $1.5 billion since 2017 as it works to build a 500-megawatt project in Utah — which would become the world’s largest “enhanced geothermal system” if completed as planned in 2028.

Fervo didn’t immediately return Canary Media’s requests for comment. When asked in December about a potential IPO, the company said by email, “We have a lot of capital needs going forward to fuel our planned growth and will be tapping a lot of different opportunities to make that happen.”

Fervo is at the fore of a fast-growing effort to unleash geothermal energy across the country. Geothermal represents only about 0.4% of total U.S. electricity generation, largely because existing technology is constrained by geography or challenging economics.

But new techniques developed by Fervo and its competitors are breathing fresh life into the century-old industry — and attracting significant funding as electricity demand soars, including from tech giants. Geothermal is also the rare form of clean energy to win acceptance from the Trump administration, which has spared the fledgling industry from the targeted policy attacks and sweeping funding cuts that it’s lobbed at wind and solar energy.

Thursday’s IPO news comes on the heels of two other major funding announcements this week from geothermal startups Zanskar and Sage Geosystems, both of which are pursuing unique approaches to harnessing Earth’s heat for providing clean, around-the-clock power.

On Wednesday, Zanskar said it raised $115 million in a Series C funding round led by Spring Lane Capital to develop its “gigawatt-scale pipeline” of projects. The Salt Lake City–based company uses AI and modern prospecting tools to identify naturally occurring reservoirs of hot water and steam that are hidden beneath the surface, without the visible signs — like vents and geysers — that typically help developers find hot spots.

Zanskar recently announced the discovery of one such geothermal system in western Nevada, which it says has the potential to produce more than 100 MW of electricity using traditional drilling technologies, marking a key proof point for the firm.

Meanwhile, Sage Geosystems said it closed over $97 million in Series B funding, in a round led by conventional geothermal giant Ormat Technologies and investment firm Carbon Direct Capital. The funding will support the build-out of Sage’s first commercial-scale project, to be located at one of Ormat’s existing power plants.

Sage’s approach to geothermal energy involves tapping into both heat and pressure from hot, dry rocks found deep underground. The company drills wells and fractures rocks to create artificial reservoirs that it pumps full of water. Sage then cycles the water in and out of the fracture and jettisons the liquid to the surface in order to drive turbines and produce electricity.

Fervo, for its part, also uses fracking tools to create artificial reservoirs for generating power. In 2023, the company hit a key milestone when it completed the world’s first commercial pilot system to use “enhanced” drilling methods. This 3.5-MW facility in Nevada was built with support from Google, which is also working with Fervo to develop 115 MW of geothermal energy to power the tech giant’s data centers in the state.

Now, along with the IPO filing, Fervo is gearing up to mark an even bigger achievement: completing the first 100 MW of its 500-MW Cape Station project in Utah and delivering power to the grid in October.

As Massachusetts faces an energy-affordability crisis, one of the state’s biggest utilities is trying a new approach to satisfy growing power demand without blowing out its grid budget and further spiking residents’ bills.

Late last year, National Grid launched a marketplace in Massachusetts that, put simply, lets the utility shop for the best customer-owned solar and batteries, smart EV chargers and appliances, and other distributed energy resources to reduce strain on the grid in specific locations.

The idea is that National Grid can strategically deploy this existing, scattered energy equipment during periods of high demand — for example, drawing power from a home battery, dialing down a business’s air conditioning, or deferring EV charging.

This relief on the grid lets the utility defer or even fully avoid upgrading the wires, transformers, and other infrastructure that deliver power to households. Such costly upgrades are the single biggest driver of rising electricity bills in the U.S.

That’s why National Grid calls it a “non-wires alternative” program — it’s finding things that can defer and reduce the costs of those grid investments.

Unlike the non-wires alternative projects that utilities have been doing for at least the past decade, this one is designed to move much more quickly and cast a much wider net for resources that can stand in for grid upgrades.

“The 2010s version is, you’ve got big players, a single project for the entire need. It’s an old-school utility procurement,” said Josh Tom, National Grid’s director of energy transition solutions. “It’s a closed system, not accessible to everyone. And it can take a long time.”

These slow, burdensome, and costly approaches have yielded only a handful of successful projects over the years. National Grid’s new program, by contrast, is built around a marketplace platform into which companies can bid resources ranging from big batteries to lots of smart thermostats.

From there, National Grid can assess how they could be combined to solve particular grid challenges at different sites on the utility’s distribution network. That should allow it to move much more quickly to find, test, and potentially pay for resources that meet its grid needs, said Nick Watson, National Grid’s director of flexible resource engineering. “We see it as more of a dynamic process,” he said.

The utility’s bidding opportunity will be open through mid-February and target providing grid relief during the summer and winter seasons from 2026 to 2030, Watson said. “We’ll assess those bids, figure out the procurements that meet our needs, using tools we’re trying out for the first time.” Contracts with winning bidders will follow, and tests of the resources are expected to begin this spring, ahead of eligible assets being dispatched in the summer, he said.

The company running National Grid’s new marketplace is the U.K.-based startup Piclo. It does similar work in its home country with National Grid Electricity Distribution, a subsidiary of the same firm that owns National Grid in Massachusetts.

Piclo is a major provider of flexibility-marketplace services in the U.K., a country that analysts say is far ahead of the U.S. on this front, and the company has expanded to mainland Europe and Australia in recent years. It’s also making inroads in the U.S. via its partnerships with Connecticut utilities and with National Grid, which has already used Piclo’s marketplace as part of its “dynamic load management” programs in New York for several years.

“We’ve done this for years in the U.K. and beyond,” said James Johnston, Piclo’s CEO. “But in a lot of the U.S., this hasn’t happened before.”

The potential could be huge, Johnston said. In September, Piclo announced that it had registered across the U.S. a combined 1 gigawatt of distributed energy resources — a term that includes batteries, EV fleets, grid-responsive appliances, and commercial and industrial buildings that can dial down energy use on demand. Companies registering with Piclo include major residential solar and battery installer Sunrun, demand-response provider Enel X, and energy-efficiency startup Budderfly.

Owners and managers of these distributed energy resources can share data on Piclo’s platform about how much power their devices can inject into the grid, store for later use, or put off consuming, Johnston said. The platform will connect those offers to entities — utilities, grid operators, and large customers like data centers that are looking for ways to mitigate their impact on the system — interested in tapping them to solve energy or grid challenges.

Unlike companies that aggregate distributed energy resources and manage them as virtual power plants, “we don’t take a position in the market,” Johnston said. “We’re that party that partners trust to share data with. We’re that matchmaker — we share the right data sets, end to end, across that entire journey. And we’re the adjudicator — whether you’re matched or not, whether you win a contract or not.”

Piclo has proved its bona fides in the U.K., where it has more than 60,000 registered distributed energy resources and has procured more than 2.6 gigawatts of flexible capacity to date.

For National Grid, Piclo’s marketplace opens up a world of possibilities, Tom said.

“They’re helping us communicate our needs to the market,” he said. “Their open marketplace is a new procurement approach.”

The current program round is looking to secure about 25 megawatts of flexibility, he said. That’s less than half the 52 megawatts secured by the largest non-wires alternative program in the country — the Brooklyn-Queens Demand Management program, launched in 2014 by utility Con Edison to relieve a congested New York City substation.

But National Grid is seeking to solve grid problems at 23 locations, each with a distinct set of needs, Tom said. Some sites require only a small amount of overload relief on a substation or circuit during a handful of hours in the summer or winter. Others may require non-wires alternatives that can be dispatched more frequently or that expand over time as new customers increase peak demands on a specific part of the grid.

One key benefit of working with Piclo’s marketplace is that it helps National Grid mix and match the capabilities of a number of different bidders, rather than forcing a single bidder to meet them all, Tom said. “What we’re really trying to do in this approach is open up the possibility for portfolios of bids that work alongside each other to meet the need in a couple of ways,” he said.

“Let’s say you have a 3-megawatt need for a summer season, a four-hour window or eight-hour window on certain days,” he said. “We want to open the possibility, even if you don’t have 3 megawatts, to bid in your 1 megawatt,” which the company will combine with megawatts from other providers to make up the difference. “That opens opportunities for those who can’t enter the market otherwise.”

Portfolios can be built across time as well as across scale, he added. “Let’s say it’s a four-hour window. If you can only provide 3 megawatts for the first two hours, someone else could provide the megawatt for hours three and four — and we have a complete portfolio.”

Once National Grid selects the distributed energy resources it wants to procure from the Piclo marketplace, the utility will have to run them through a gauntlet of tests to ensure they’re reliable enough to relieve grid stresses.

“There are a bunch of test dispatch requirements before we run a real event or renumerate a party for services provided,” Tom said. This spring and summer will be dedicated to running those tests and to fine-tuning the “contractual structures with the right characteristics to ensure we’re comfortable in the future.”

Regulator support has been critical in setting this up, he added. Massachusetts’ three major investor-owned utilities are required to develop grid-modernization plans under a 2022 energy and climate law that sets the state on a course to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. In approving those plans, the state let utilities create grid services compensation funds that can pay for non-wires alternative programs, he explained.

Launching Piclo’s marketplace isn’t National Grid’s only attempt at a non-wires alternative program in Massachusetts. The utility is also expanding a 7-year-old program called ConnectionSolutions, which regulators required all the state’s investor-owned utilities to deploy. This program is designed not to relieve local grid constraints but rather to reduce overall peak demands on power plants and transmission grids. In that role, it has delivered hundreds of megawatts of grid relief during summer heat waves and become a national model for virtual power plants.

Now, National Grid wants to see if the program can also help defer or avoid upgrades at specific grid substations and circuits. The expanded version, ConnectedSolutions+, offers customers incremental incentives to install and sign up resources in areas with local grid needs.

What distinguishes ConnectedSolutions+ from National Grid’s work with Piclo is that the latter program targets not just customers with smart thermostats, EV chargers, grid-responsive appliances, and battery storage but also larger grid-connected energy assets like community solar arrays and batteries, Tom noted. Massachusetts has a lot of community solar that’s been challenging to connect to the grid, and the state has been working for years to find a way to use those solar and battery systems to relieve grid stresses.

Importantly, National Grid’s first round of non-wires alternatives is targeting spots that aren’t in dire need of grid upgrades, Tom said. “We’re not putting at risk the safety and reliability of the network by doing this.”

Another key target for National Grid is for “bridge-to-wires” needs, Watson said — spots where new customers that use a lot of power want to plug into the grid and “you can’t build the infrastructure quickly enough” to accommodate them, he said. Distributed energy resources can bridge the grid overloads until the necessary upgrades take place.

One big question that utilities must grapple with is when a non-wires alternative makes financial sense. After all, a utility must pay the customers handing over the reins to their distributed energy resources. Utilities also can’t avoid upgrading their grids forever — and changing circumstances can wreak havoc on the assumptions that inform how much a non-wires alternative is worth.

Utilities must account for a ton of variables to determine the value of deferring grid investments versus biting the bullet and investing in must-have upgrades or expansions, Watson said. “We’ve been developing methodologies to help us do that over the course of this year,” he said. “It depends on what the use case is.”

Although non-wires alternatives are catching on, they face an uphill battle. Regulated utilities in the U.S. earn guaranteed profits on every dollar they invest in their grid infrastructure — an inherent disincentive for them to seek out alternatives to grid investment, even if they could save customers money over time.

But from Watson’s perspective, utilities will have to find better ways to manage their grids in the long run, as power demand grows, distributed solar and batteries proliferate, and electric vehicles and buildings add both new strains and new sources of flexibility to the system.

“Traditionally, it isn’t the business model of the investor-owned utility to leverage flexibility,” he said. But to meet state goals around electrification and emissions reductions, “we’re going to have to change the way we manage our network. We can’t just continue to build out the network in the traditional ways we have in the past.”

Stegra’s grand plan to build the first large green-steel mill in the world has recently hit a rough patch. Faced with increasing project costs and construction delays, the Swedish startup has been seeking to raise over $1 billion in additional financing since last fall to complete the flagship facility near the Arctic Circle.

Last week, though, Stegra shared some brighter news: The company landed a major new customer, marking a step forward for the beleaguered project.

A subsidiary of the German conglomerate Thyssenkrupp has agreed to buy a certain type of steel from Stegra’s plant in northern Sweden, which is set to start operations next year. The plant will use green hydrogen — made with renewable energy — and clean electricity to produce iron and steel. The sprawling facility is expected to initially produce 2.5 million metric tons of steel annually and eventually double its production of the metal.

Stegra, formerly H2 Green Steel, estimates that its process will slash carbon dioxide emissions by up to 95% compared with traditional coal-based methods, which account for up to 9% of global emissions.

Thyssenkrupp Materials Services said it would buy tonnages in the “high-six-digit range” of “non-prime” steel — metal that doesn’t meet the high-quality standards required for certain uses but that is still strong and durable enough for other applications. Steel mills typically produce a higher ratio of non-prime metal when they’re starting up, which decreases over time, according to Stegra. The deal should help the firm generate cash flow when the plant first opens.

“A partner for non-prime steel is important for the ramp up of our steel mill,” Stephan Flapper, head of commercial at Stegra, said in a Jan. 12 statement. “Together we can drive an even stronger pull for steel products made via the green hydrogen route.”

The deal is Stegra’s first for non-prime steel, though the startup has already inked agreements for prime steel with automakers such as Mercedes-Benz, Porsche, and Scania, as well as major companies including Cargill, Ikea, and Microsoft. The offtake contracts represent more than half the steel that will be produced during the plant’s first phase.

Notably, Thyssenkrupp Materials Services won’t count the carbon-emission reductions associated with the green steel toward its own climate targets. Instead, Stegra will separately sell the green credentials, in the form of environmental attribute certificates, to other customers in the prime steel market. Stegra previously struck a deal to sell certificates to Microsoft — which is an investor — to help offset emissions from conventionally made steel that the tech giant is using to build data centers outside Europe.

The startup’s announcement with the Thyssenkrupp subsidiary didn’t include details about the financial value or other parameters of the multiyear agreement. Stegra didn’t respond to Canary Media’s requests for comment.

Analysts said the lack of specifics makes it difficult to know exactly how meaningful this development is for the Swedish steelmaker as it works to address its financial challenges.

“This gives a positive signal … that they’re moving in the right direction,” said Anne-Sophie Corbeau, a Paris-based hydrogen analyst at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. “But it’s really complicated to quantify how significant this is.”

The new deal with Thyssenkrupp and the previous one with Microsoft “suggest Stegra has a technically sound product,” Brian Murphy, head of hydrogen and low-carbon gas for S&P Global Energy, said by email. He added that, in general, signing long-term offtake deals for clean-hydrogen projects has become “the key unlock” for developers to secure necessary financing.

Still, “more price information is required to assess the full impact on Stegra’s financial position,” he said.

Stegra is forging ahead with its multibillion-dollar project even as other European steelmakers put their hydrogen-fueled ambitions on ice.

Last year, Thyssenkrupp Steel and the industrial giant ArcelorMittal said they were canceling or postponing projects in Europe, citing the economic headwinds and uncertain market conditions facing green steel and hydrogen production. The setbacks come even as the European Union is increasing regulatory pressure on steelmakers inside the bloc and globally to curb CO2 emissions from industrial facilities. In the United States, meanwhile, plans for two marquee green-steel projects were shelved last year.

Construction on Stegra’s plant in northern Sweden was 60% complete as of late October, and the company continues to share snapshots of ongoing work at its snow-covered site on social media. Stegra’s success, if it comes, could reinvigorate green-steel efforts across the region, particularly if the company can sell its steel at prices that cover the higher costs of making low-carbon metal, Corbeau said.

“In the end, if the economics work and they manage to sell most of the steel at a premium, that will be a good signal for a lot of the other companies that have been hesitant,” she said.

The Double Island Volunteer Fire Department in Yancey County, North Carolina, is the beating heart of this remote community in the shadow of Mount Mitchell, about 50 miles northeast of Asheville. Once home to a schoolhouse that doubled as a church, the red-roofed building still hosts weddings, parties, and other events.

“It was built to serve as a community center,” said Dan Buchanan, whose family has lived in the area since 1747 and whose mother attended the school as a young girl. “A place to gather.”

Sixteen months ago, when Hurricane Helene hit this rugged corner of countryside with catastrophic floods, Double Island’s fire department was where locals turned for help.

“This is [our] ‘downtown,’” said Buchanan, who serves as the assistant fire chief. “In the wake of the storm, people were like, ‘Let’s get to the fire station.’ That was the goal of everybody.”

Fresh out of retirement and living back in his hometown to care for his ailing mother, Buchanan drew on his long career in emergency response to spring into action. With the station, powered by generators, serving as their command center, he and his neighbors gathered and distributed food, water, and other provisions to those in need. They hacked through downed limbs and sent out search teams.

“By the end of the fourth day, we had accounted for all the residents of the Double Island community,” Buchanan said. And while no one in the enclave died because of the hurricane, some suffered while they waited for medications like insulin.

A lack of drinking water and limited forms of communication were also huge obstacles. “When we finally got the roads cleared, and people could get in here, we were literally writing down our needs on a notepad and giving it to whomever, and then they would ferry supplies,” Buchanan said. “A carrier pigeon would have been nice.”

Helene was a “once in 10 lifetimes” storm, Buchanan said, with devastation he and the community hope to never see again. But more extreme weather events are all but certain thanks to climate change, and today Double Island is better prepared.

The station is equipped with a microgrid of 32 solar panels and a pair of four-hour batteries. The donated equipment will shave about $100 off the fire department’s monthly electric bill, meaningful savings for an organization with an annual operating budget of just $51,000.

When storms inevitably hit, felling trees and downing power lines, the self-sustaining microgrid can provide some electricity and an internet signal.

“We’ll have at least a way to run our radio equipment, run our well and basic lighting and refrigeration,” Buchanan said, adding that the latter was vital for medication. “It may not seem like much — but that’s the Willy Wonka golden ticket.”

Communication, he stressed, was key. “If you can’t communicate, you can’t get the help you need.”

The microgrid project, called a resilience hub, was made possible by a network of government and nonprofit groups that came together after Helene to help fire departments like Double Island and other community centers with long-term recovery. Now, a state grant program is injecting a burst of funds into their efforts. Using both public and private time, know-how, and money, the program aims to create a model for resilience that can be replicated nationwide.

“We aren’t only preparing for a disaster; we’re also helping utility diversification, cost savings, and normalization of the technology,” said Jamie Trowbridge, a senior program manager at Footprint Project, a leading nonprofit in the initiative. Those benefits aren’t unique to Yancey County, he said. “We’d like to see this be a pilot for us on what scalable microgrid technology could be across all of western North Carolina — and maybe the country.”

The Double Island experience was common in the immediate aftermath of Helene. Across the region, communities isolated by closed roads and mountainous terrain turned to their fire departments for help.

That’s part of how Kristin Stroup got involved in the resilience hub effort. Based in Black Mountain, a popular tourist destination 15 miles east of Asheville, Stroup helped start a corps of volunteers who gathered at the town’s visitor center. In coordination with an emergency operations center based at Black Mountain’s main fire station, she led over 200 volunteers in doing whatever they could, from cooking and doling out food to making the country roads passable.

“People [were] just driving around the town with chain saws,” said Stroup, today a senior manager in energy and climate resilience with the nonprofit Appalachian Voices. The weekend after Helene hit, she said, “Footprint rolled into town with a bunch of solar panels. I became an instant part of their family.”

With founders who cut their teeth in international aid, the New Orleans–based Footprint Project had teamed up with the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, Greentech Renewables Raleigh, and others to pool donations of batteries, solar panels, and other equipment to deploy microgrids to dozens of sites in the region before the end of 2024. From Lake Junaluska to Linville Falls, recipients included fire stations such as the one in Double Island and an art collective in West Asheville.

By February 2025, Footprint had hired Trowbridge and another staff person to work in the area permanently. Footprint continued to cycle microgrid equipment throughout the region from its base of operations in Mars Hill, a tiny college town 20 miles north of Asheville that was virtually untouched by Helene. It launched the WNC Free Store, which donates solar panels and other supplies to residents still far from recovery — like those living out of RVs and school buses after losing their homes.

From the outset, Footprint had a critical local ally in Sara Nichols, the energy and economic development manager at the Land of Sky Regional Council, a local government partnership encompassing four counties that stretch from Tennessee to South Carolina.

“A lot of the other organizations we saw come through in the same way Footprint did, most of them did not stay. They leverage resources to do really important work, and when that work feels done, they go home,” Nichols said. “The fact that Footprint is working thoughtfully to figure out how our recovery and resiliency can be taken care of — while also thinking about their own organizational strategic growth — means a lot to me. They’ve been incredible partners.”

To be sure, assistance and rebuilding in the region are ongoing, and many systemic inequities exacerbated by the storm can’t be solved with a solar panel. But the power is back on. The cell towers are functioning. The roads are open. Piles of debris, from fallen limbs to moldy furniture, have been cleared. In relief parlance, western North Carolina is beginning to see “blue skies.”

That’s why it’s all the more important that Footprint, Appalachian Voices, and other local collaborators haven’t let up in their efforts. The web of organizations involved is thick and, seemingly, ever expanding. Last fall, the network announced it was deploying five resilience hubs around the region, including the Double Island project and a permanent microgrid at a community center in Yancey County.

“These projects, driven by a small group of determined partners, have accelerated Appalachia’s long-term resilience and preparedness,” Invest Appalachia, another nonprofit partner, said in a news release.

Now, the local public-private effort is getting a boost from the state of North Carolina. Under the administration of Gov. Josh Stein, a Democrat who has made Helene recovery a centerpiece of his first-term agenda, the State Energy Office will deploy $5 million from the Biden-era Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to install up to 24 microgrids across six western counties impacted by Helene.

The money will also go to two mobile aid units for rural counties on either end of state — one in the east and one in the west. Dubbed “Beehives” by Footprint, these solar-powered portable units will be full of equipment that can be deployed to purify water, set up temporary microgrids, and otherwise respond to storms and extreme weather.

Expected recipients of the stationary microgrids could include first responders like the Double Island Fire Department and second responders like community centers. Peer-to-peer facilities and small businesses are also encouraged to apply.

Land of Sky and other stakeholders are choosing grantees on a rolling basis through next summer. There’s already been an inundation of applicants, and six grantees have been selected, including a community center about a dozen miles up the road from Double Island in Mitchell County. But organizers say they need more interest from outside the Land of Sky region, especially in Avery County, north of Yancey on the Tennessee border; and Rutherford County, east of Asheville, which includes Chimney Rock, a village that was infamously devastated by Helene and is slowly rebuilding.

Geographic distribution isn’t the only problem organizers have faced. Some entities — while undoubtedly deserving of assistance — aren’t appropriate for the government grant because they are located in areas at risk of future flooding.

“A battery underwater is not that useful,” Trowbridge said, “so if your site is in a floodplain, maybe this isn’t the right fit for you. But we definitely want you to know about the Beehive.”

Above all, organizers like Nichols, a passionate promoter of the Appalachian Region, are determined to ensure that the state’s effort is not the be-all and end-all of resilience.

“What we’re being tasked with as recipients of this money is to try and figure out how we make this a much bigger project,” she said. “That means we’ve brought in other partners like Invest Appalachia. We’ve been seeking other kinds of money. We’re using this state money to successfully build what could be a much more comprehensive resiliency hub model.”

She added that communities across the country — even if they think they’re safe from extreme weather and climate disaster — could take cues from the western North Carolina example.

“We were a place that was not supposed to get a storm,” Nichols said. “We were a climate haven.”