Federal regulators are demanding that PJM Interconnection, the country’s biggest power market, find a faster way to connect data centers to the grid without spiking energy costs or threatening reliability.

Those regulators and other energy experts increasingly believe that a practice known as flexible interconnection is key to juggling those imperatives — and a recent study offers compelling supporting evidence.

Flexible interconnection is simple in principle: Power-hungry customers like data centers supply their own power during the handful of hours per year when overstressed grids can’t handle their needs, allowing them to get online much faster and also save money for customers at large.

But to date, only a handful of utilities and grid operators have developed the technical and regulatory structures to make flexible interconnection a reality.

Astrid Atkinson, CEO of Camus Energy, and Carlo Brancucci, CEO of Encoord, whose companies aim to enable flexible interconnection, say that PJM could deploy the practice on a large scale. That argument is backed by a unique analysis of real-world conditions — modeled across every hour of the year on the same transmission grids that PJM manages — conducted by Camus, Encoord, and Princeton University’s ZERO Lab.

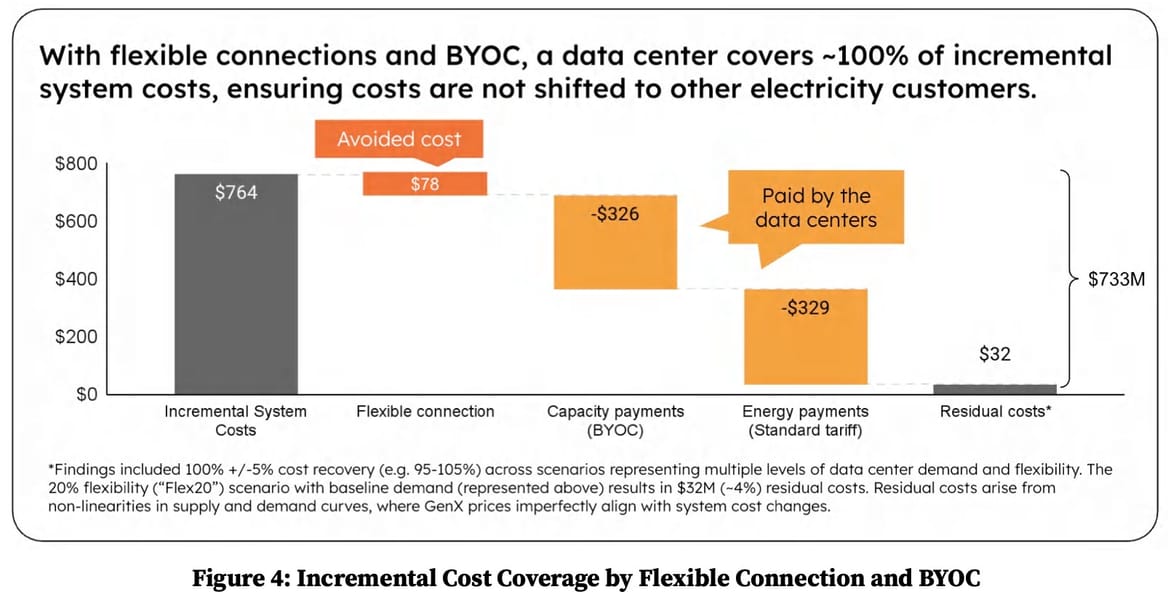

Their December report looks at six sites in mid-Atlantic states served by PJM. It concludes that a 500-megawatt data center using flexible interconnection and providing its own power during times of peak demand could connect three to five years faster than one that has to wait for grid upgrades and new power plants to be built in order to support its full power needs. By paying for the resources to cover any peak demand deficits, these flexible data centers would avoid passing those grid and generation costs on to customers already struggling with rising energy bills tied to data center growth, the report contends.

What’s more, the methods used in the report can be used by grid operators and utilities in PJM and across the country to enable other real-world flexible interconnection studies using standard interconnection tools and datasets, Brancucci said. “Everything else flows from that — what type of interconnection you need, what type of flexibility you need, what kind of contracts and agreements you need.”

“Our companies both offer commercial products that can do this,” said Atkinson, who co-founded Camus in 2019 after leading the team that maintains reliable computing for Google, the report’s sponsor and the preeminent tech giant working on real-world flexible interconnection projects today. In fact, she said, “we’re doing commercial modeling of similar sites right now.”

Data center flexibility is a hot topic. Recent reports from Duke University, think tank RMI, and analytics firms GridLab and Telos Energy all explore its viability and benefits.

But the report from Camus, Encoord, and ZERO Lab differs in a few ways that make it a far more practical blueprint for flexible interconnection, Atkinson said.

The first thing that distinguishes their report is that it uses in-depth, real-world data.

To approve flexible interconnections, utilities, grid operators, and data center developers must have data on power flows from generators across high-voltage transmission grid networks to giant power users. “You do need privileged data access to do this,” Atkinson said — and other research teams haven’t had that access.

But Camus, which provides grid orchestration software for utilities across the United States, including Pennsylvania’s PPL Electric Utilities and Duquesne Light Co., has that data for the six sites it modeled, Atkinson said. She wouldn’t reveal which utilities provided the data or the location of the sites, which in the report were given animal names such as Koala, Pony, Shark, and Whale. But she did confirm that they represent realistic targets for flexible interconnection.

The second thing that sets the report apart, according to Brancucci, is that it integrates the real-world operating conditions and constraints of the transmission networks serving data center sites. To do that, they used Encoord’s software platform, which simulates how real-world transmission networks operate during all 8,760 hours of the year.

“A 500-megawatt demand will have major impacts on any utility,” said Brancucci, who co-founded Encoord in 2019 after working as a senior research engineer at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Colorado and as a researcher at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre. “That will change the way power flows. And when power flow changes, you need to consider different security constraints.”

Such analyses consider not just business-as-usual conditions but also emergencies when power plants or transmission lines fail and grid operators must act quickly to prevent widespread outages. “This is the type of transmission analysis any ISO or utility is going to do when considering new load,” he said, and it’s a must-have for approving a new 500-megawatt customer.

Encoord works with transmission system operators and utilities struggling to ensure reliable service under a variety of conditions, including during winter storms when fossil gas systems fail. “If 10 utilities and 10 hyperscalers came to us and said, ‘We want to interconnect across 10 sites,’ we could redo this easily,” Brancucci said.

The results for the six sites in the December report show that transmission constraints would force four of them to curtail significant portions of their 500-megawatt peak power demand or build enough on-site generation and battery storage to cover these gaps — but only for less than 35 hours per year. The other two sites did not have transmission constraints.

The third thing that distinguishes their report is that they were able to tap into a model developed by researchers at ZERO Lab and MIT to assess how adding data centers to the grid would affect the amount of generation capacity that PJM needs to cost-effectively meet peak electricity demand.

That model enabled them to analyze how individual data centers could secure a mix of faster-to-build power sources, including solar power, wind power, and hybrid renewable-battery systems, as well as secure commitments from other customers willing to lower their power use to cover data centers’ needs through demand response or virtual power plants.

Ultimately, the new data underscores in the most definitive terms yet that flexible interconnection is viable in PJM, Atkinson said. And if PJM were to allow it, data center developers would likely be more than willing to take on the responsibility of securing their own resources to relieve those rare constraints, she added. Doing so could allow them to get online in two or three years, rather than needing to wait five to seven years for new transmission or generation.

“Data centers are willing to pay more if they can connect, in many cases, because the opportunity costs” of being forced to wait for years “far outweigh the costs of capacity,” she said. “They just need to know how much they need to build.”

And once they’re armed with that knowledge, data centers can take on the cost of securing their own resources, which would almost completely eliminate the need to build more grid infrastructure and power plants, reducing costs for all PJM customers, according to the report.

PJM isn’t the only grid operator or utility facing data center–driven cost pressures. But its challenges are more acute than most. PJM has a massive interconnection backlog that has created multiyear delays for new generation seeking to connect to its grid. And its capacity market structure is forcing up utility rates today to cover the future costs of serving forecasted data center demand.

PJM hasn’t been able to gain consensus from stakeholders — including utilities, power plant owners, big corporate energy users, and data center developers — on how to fix these problems, even as the more than 67 million customers that get power from PJM’s system face spiking utility bills to cover those costs.

That lack of consensus has prevented PJM from developing a key policy that could allow flexible interconnection to happen, Atkinson said. In order for the method laid out in the December report to work, PJM and member utilities would need to allow data centers to interconnect via something called “conditional firm” grid service.

In simple terms, this means blending traditional, “firm” service for the portion of power needs that can be supplied without grid upgrades and “conditional” service, which requires data centers to cut their power use or supply their own electricity needs during critical hours.

PJM doesn’t provide this kind of option for customers — though it may have it soon enough. In December, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ordered PJM to create structures that would allow data centers and other big customers to connect to its grid in more flexible ways. That order set out a variety of methods for PJM to pursue, including a structure called “interim non-firm transmission service,” which closely approximates the conditional firm service that Camus and Encoord envision.

“At its core, the FERC order moves PJM away from ‘full freight’ assumptions and toward studying and serving large loads based on their actual time-varying grid use,” Brancucci said. “That’s exactly the premise behind the conditional firm service model we analyzed in a few locations in PJM.”

Similar innovations are being pursued by grid operators in the Midwest and Texas, Atkinson noted. The Department of Energy has ordered FERC to launch a fast-track rulemaking to require grid operators and utilities to expedite data center interconnections.

“Today, no market really allows you to have a mix of grid power and on-site power that’s reasonably managed,” Atkinson said. But a growing number of grid experts agree that flexible interconnection is, as she put it, “the only practical way to meet these requirements.”

An enormous and novel energy storage project could soon break ground in California after receiving state approvals just before Christmas.

The startup Hydrostor’s Willow Rock project would store 500 megawatts of power that could be injected into the grid for up to eight hours, totaling 4 gigawatt-hours. That’s more gigawatt-hours than any lithium-ion battery offers, and a rare step forward for a major long-duration energy storage project. Once online, it could prove a crucial tool for California, where intermittent solar generation has become the state’s top source of electricity.

Hydrostor received permission to start building from the California Energy Commission, which signs off on environmental approvals for large thermal power plants. This has become a rarity in an era when the state pretty much exclusively builds solar and battery plants. Hydrostor, however, compresses air in underground caverns and then releases it to turn conventional turbines and send power back to the grid. Its roster of equipment put the project under the commission’s jurisdiction.

“These are the major approvals. It basically allows us to get to a shovel-ready status,” Jon Norman, president of Hydrostor, told Canary Media.

That means Hydrostor can technically begin construction on the 88.6-acre parcel it controls, where rural Kern County hits the Mojave Desert.

But Hydrostor won’t actually start building until it secures paying customers for the full planned capacity. So far, Central Coast Community Energy has contracted for 200 megawatts of Willow Rock’s capacity. Hydrostor is negotiating contracts for another 50 to 100 megawatts, which leaves 200 to 250 megawatts up for grabs.

That uncontracted capacity stands in the way of Hydrostor securing the financing it needs to pay for the roughly $1.5 billion project. Lenders or investors want assurances that the innovative installation will make enough money to pay them back, with a return. Otherwise, the project is exposed to merchant risk: Maybe Hydrostor could build it anyway, bid into the wholesale markets, and make good money. But that’s too risky a bet for most financiers, who want to see firm customer commitments.

Two factors further complicate the pitch to financiers. Because Hydrostor is trying to build a fundamentally new type of storage plant, there isn’t a clear market comparison to benchmark against. And it’s also competing in a fundamentally new type of market niche: long-duration storage.

Many analysts have predicted the physical need for longer-term grid storage as more and more of a region’s electricity comes from wind and solar power. Few regions have developed workable market structures to get ahead of that need, since today’s power markets focus on short-term optimization rather than long-term infrastructure planning.

California, though, has supplemented its power markets with a centrally driven push for long-duration storage. The state’s utility regulator required power providers to procure a collective 1 gigawatt of storage that lasts for eight or more hours. That order prompted Central Coast Community Energy to sign the deal with Hydrostor.

In September, the California Public Utilities Commission recommended a portfolio including 10 gigawatts of eight-hour storage for 2031, as part of the state’s planning for its transition to 100% clean electricity. That means a procurement order could come soon, and Hydrostor, with its permits in order, would be in position to compete for that.

“They’ve identified the need for very near-term procurement, so we’re looking forward to participating in that,” Norman said. “We also know that we’re very competitive.”

He also said it’s “very likely” that Hydrostor breaks ground this year.

That would kick off an estimated four-to-five-year construction timeline, Norman said. The company has created a “pretty sophisticated Joshua tree management plan” to protect the alien-looking vegetation unique to the Mojave, where it will build the project. It also secured a water supply and place to deposit the rock it carves from the earth, and it is currently finalizing an engineering, procurement, and construction contractor, Norman said.

That timeline should put Willow Rock in a good place to help California meet those medium-term storage needs. Given current trends, in five or so years the state will be even more awash in surplus solar generation at midday, and in even greater need of on-demand energy to keep the lights on after the sun sets.

In other words, if the regulator’s numbers are right, California will need many more Willow Rocks to keep up, so it’s about time one of them got going.

Those in the energy sector, like everyone else, could not stop talking about artificial intelligence this year. It seemed as if every week brought a new, higher forecast of just how much electricity the data centers that run AI models will need. Amid the deluge of discussion, an urgent question arose again and again: How can we prevent the computing boom from hurting consumers and the planet?

We’re not bidding 2025 farewell with a concrete answer, but we’re certainly closer to one than we were when the year started.

To catch you up: Tech giants are constructing a fleet of energy-gobbling data centers in a bid to expand AI and other computing tools. The build-out is encouraging U.S. utilities to invest beaucoup bucks in fossil-fueled power plants and has already raised household electricity bills in some regions. Complicating things further is that many of today’s proposed data centers may never get built, which would leave the rest of us to foot the bill for expensive and unnecessary power plants that bake the planet.

It’s all hands on deck to find solutions. Lawmakers across every state considered a total of 238 bills related to data centers in 2025 — and a whopping half of that legislation was dedicated to addressing energy concerns, according to government relations firm MultiState.

Meanwhile, the people who operate and regulate our electric grid worked on rules to get data centers online fast without breaking the system. One idea in particular gained traction: Let the facilities connect only if they agree to pull less power from the grid during times of über-high demand. That could entail literally computing less, or outfitting data centers with on-site generators or batteries that kick in during these moments.

Even the Trump administration got in on the action, with Energy Secretary Chris Wright directing federal regulators in October to come up with rules that would let data centers connect to the grid sooner if they agree to be flexible in their power use. But this idea of “load flexibility” is still largely untested and has its skeptics, who argue that it’s technically unrealistic under current energy-market frameworks.

And then there are the hyperscalers themselves. Big tech companies with ambitious climate goals are signing power purchase agreements left and right for energy sources from geothermal to nuclear to hydropower. Google unveiled deals with two utilities this summer to dial down data centers’ power use during high demand. Texas-based developer Aligned Data Centers announced this fall that it would pay for a big battery alongside a computing facility it’s building in the Pacific Northwest, allowing the servers to get up and running way faster than if the company waited for traditional utility upgrades.

Expect more action on this front in 2026. Local opposition to data centers is on the rise, power-demand projections are still climbing, and speculation is mounting that the entire AI sector fueling those forecasts is a big old bubble about to pop.

Since spring of last year, North Carolina’s largest utility has been testing whether household batteries can help the electric grid in times of need — and now the company wants to roll out the plan to businesses, local governments, and nonprofits, too.

Duke Energy has already paid hundreds of North Carolinians to let it tap power from their home storage systems when electricity demand is highest. It’s Duke’s first foray into running a “virtual power plant,” in which the company manages electricity produced and stored by consumers, much as it would control generation from its own facilities.

In September, the utility proposed a similar model for its nonresidential customers, asserting that the scheme will save money by shrinking the need for new power plants and expensive upgrades to the grid. The recognition signals a way forward for distributed renewable energy and storage as state and national politicians back away from the clean energy transition.

The initiative now needs approval from the five-member North Carolina Utilities Commission, where the virtual-power-plant model has faced some skepticism. But the apparent merits of Duke’s plan, which has broad backing, may be too enticing for commissioners to ignore — especially when the state is grappling with rising rates and voracious demand from data centers and other heavy electricity users.

“In an era of massive load growth, something that should lower costs to customers while helping meet peak demand — to me, it’s an absolute no-brainer,” said Ethan Blumenthal, regulatory counsel for the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, an advocacy group. “I’m hopeful that [regulators] see it the same way.”

Duke’s trial residential battery incentives grew out of a compromise with rooftop solar installers. Like many investor-owned utilities around the country, the company sought to lower bill credits for the electrons that solar owners add to the grid. When the solar industry and clean energy advocates fought back, the scheme dubbed PowerPair was born.

The test program provides rebates of up to $9,000 for a battery paired with rooftop photovoltaic panels. It’s capped at roughly 6,000 participants, or however many it takes to reach a limit of 60 megawatts of solar. Half of the households agree to let Duke access their batteries 30 to 36 times each year, earning an extra $37 per month on average; the other half enroll in electric rates that discourage use when demand peaks.

The incentives have been crucial for rooftop solar installers, who’ve faced a torrent of policy and macroeconomic headwinds this year, and they’ve proved vital for customers who couldn’t otherwise afford the up-front costs of installing cheap, clean energy.

But the PowerPair enrollees already make up 30 megawatts in one of Duke’s two North Carolina utility territories and could hit their limit in the central part of the state early next year, leaving both consumers and the rooftop solar industry anxious about what’s next.

Duke’s latest proposal for nonresidential customers — which, unlike the PowerPair test, would be permanent — is one answer.

The proposed program is similar to PowerPair in that it’s born of compromise: Last summer, the state-sanctioned customer advocate, clean energy companies, and others agreed to drop their objections to Duke’s carbon-reduction plan under several conditions, including that the utility develop incentives for battery storage for commercial and industrial customers. The Utilities Commission later blessed the deal.

“This was pursuant to the settlement in last year’s carbon plan,” said Blumenthal, “so it’s been a long time coming.”

While many industry and nonprofit insiders refer to the scheme as “Commercial PowerPair,” its official title is the Non-Residential Storage Demand Response Program.

That name reflects the incentives’ focus on storage, with solar as only a minor factor: Duke wants to offer businesses, local governments, and nonprofits $120 per kilowatt of battery capacity installed on its own and just $30 more if it’s paired with photovoltaics.

The maximum up-front inducement of $150 per storage kilowatt is much less than the $360 per kilowatt offered under PowerPair. But more significant for nonresidential customers could be monthly bill credits: about $250 for a 100-kilowatt battery that could be tapped 36 times a year, plus extra if the battery is actually discharged.

Unlike households participating in PowerPair, which must install solar and storage at the same time to get rebates, nonresidential customers can also get the incentives for adding a battery to pair with existing solar arrays.

“That could be very important for municipalities around North Carolina that have already installed a very significant amount of solar, but very little of that is paired with battery storage,” said Blumenthal.

Duke has high hopes for the program, projecting some 500 customers to enroll. Five years in, the resulting 26 megawatts of battery storage would help it avoid building nearly 28 megawatts of new power plants to meet peak demand, saving over $13.6 million. That’s significantly more than the cost of providing and administering the incentives, which Duke places at nearly $11.8 million.

“The Program provides a source of cost-effective capacity that the Company’s system operators can use at their discretion in situations to deliver economic benefits for all customers,” Duke said in its September filing to regulators. “Importantly, the Company received positive feedback from its customers … when sharing the details of the Program.”

Indeed, the proposal has been met with support not just from the Sustainable Energy Association and other clean energy groups but also organizations like the North Carolina Justice Center, which advocates for low-income households. It earned praise from local governments represented by the Southeast Sustainability Directors Network and conditional support from the state-sanctioned customer advocate, known as Public Staff, too.

The good vibes continued last week, when Duke responded positively to detailed suggestions from these parties on how to improve the program. That included a request from Public Staff that the company raise the per-customer limit on battery capacity to align with the maximum amount of solar that a business or other nonresidential consumer can connect to the grid, which is currently 5 megawatts.

“Larger batteries sited at larger customer sites can help provide more significant system benefits and can reduce the need for incremental utility-owned energy storage installed at all ratepayers’ expense,” the agency told regulators in its November comments. It recommends a cap tied to a customer’s peak demand; for example, a business that consumes more energy at once should get incentives for a bigger battery. Duke agreed in its Dec. 5 comments, calling that limit “reasonable.”

Still, questions remain about how to make the incentives most impactful.

Public Staff, for instance, believes Duke should increase its monthly payment to customers for keeping their batteries charged and ready to deploy. This “capacity credit” is now set at $3.50 per kilowatt but effectively reduced to $2.48, because the utility assumes that a percentage of users won’t properly maintain their systems, based on its experience with households. The company calls that a “capability factor,” but the agency dubs it “collective punishment” for all customers and says it should be eliminated or recalibrated for “more sophisticated” nonresidential participants.

Raleigh, North Carolina–based 8MSolar, a member of the Sustainable Energy Association, is among the many installers that have been eagerly anticipating Duke’s proposal.

The program on its own likely won’t “move the needle unless the incentives get bumped up,” said Bryce Bruncati, the company’s director of sales. However, the scheme could tip the scales for large customers when stacked on top of two federal tax opportunities: a 30% incentive available through the end of 2027 and a deduction tied to the depreciation value of the system — up to 100% thanks to the Republican budget law passed this summer.

“The combined three could really have a big impact for small- to medium-sized commercial projects,” Bruncati said. The Duke program would represent “a little bit of icing on the cake.”

Whatever their size and design, the fate of the incentives rests entirely with the Utilities Commission, now that the final round of comments from Duke and other stakeholders is in. There’s no timeline for a decision.

At least one commissioner, Tommy Tucker, has voiced skepticism about leveraging customer-owned equipment to serve the grid at large. “I’m not a big fan of the [demand-side management] or virtual power plants because you’re dependent upon somebody else,” the former Republican state senator said at a recent hearing, albeit one not connected to the Duke program.

Still, Blumenthal waxes optimistic. After all, Tucker and three other current members of the commission are among those who ruled last year that Duke should present the new incentive program.

“They seem to recognize there is value to distributed batteries being added to the grid,” Blumenthal said. “The fact that [the proposal] is cost-effective is key because the idea is, the more of it you do, the more savings there are.”

Two corrections were made on Dec. 10, 2025: This story originally misstated the number of times a year that Duke can tap a PowerPair participant’s battery; it is 30 to 36 times a year, not 18. The story also originally misstated the enrollment Duke expects for the nonresidential program; the utility expects 26 megawatts of batteries, not 26,000 customer participants.

Extreme weather is making the grid more prone to outages — and now FirstEnergy’s three Ohio utilities want more leeway on their reliability requirements.

Put simply, FirstEnergy is asking the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio to let Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co., Ohio Edison, and Toledo Edison take longer to restore power when the lights go out. The latter two utilities would also be allowed slightly more frequent outages per customer each year.

Comments regarding the request are due to the utilities commission on Dec. 8, less than three weeks after regulators approved higher electricity rates for hundreds of thousands of northeast Ohio utility customers. An administrative trial, known as an evidentiary hearing, is currently set to start Jan. 21.

Consumer and environmental advocates say it’s unfair to make customers shoulder the burden of lower-quality service, as they have already been paying for substantial grid-hardening upgrades.

“Relaxing reliability standards can jeopardize the health and safety of Ohio consumers,” said Maureen Willis, head of the Office of the Ohio Consumers’ Counsel, which is the state’s legal representative for utility customers. “It also shifts the costs of more frequent and longer outages onto Ohioans who already paid millions of dollars to utilities to enhance and develop their distribution systems.”

The United States has seen a rise in blackouts linked to severe weather, a 2024 analysis by Climate Central found, with about twice as many such events happening from 2014 through 2023 compared to the 10 years from 2000 through 2009.

The duration of the longest blackouts has also grown. As of mid-2025, the average length of 12.8 hours represents a jump of almost 60% from 2022, J.D. Power reported in October.

Ohio regulators have approved less stringent reliability standards before, notably for AES Ohio and Duke Energy Ohio, where obligations from those or other orders required investments and other actions to improve reliability.

Some utilities elsewhere in the country have also sought leeway on reliability expectations. In April, for example, two New York utilities asked to exclude some outages related to tree disease and other factors from their performance metrics, which would in effect relax their standards.

Other utilities haven’t necessarily pursued lower targets, but have nonetheless noted vulnerabilities to climate change or experienced more major events that don’t count toward requirements.

FirstEnergy’s case is particularly notable because the company has slow-rolled clean energy and energy efficiency, two tools that advocates say can cost-effectively bolster grid reliability and guard against weather-related outages.

There is also a certain irony to the request: FirstEnergy’s embrace of fossil fuels at the expense of clean energy and efficiency measures has let its subsidiaries’ operations and others continue to emit high levels of planet-warming carbon dioxide. Now, the company appears to nod toward climate-change-driven weather variability as justification for relaxed reliability standards.

FirstEnergy filed its application to the Public Utilities Commission last December, while its recently decided rate case and other cases linked to its House Bill 6 corruption scandal were pending. FirstEnergy argues that specific reliability standards for each of its utilities should start with an average of the preceding five years’ performance. From there, FirstEnergy says the state should tack on extra allowances for longer or more frequent outages to “account for annual variability in factors outside the Companies’ control, in particular, weather impacts that can vary significantly on a year-to-year basis.”

“Honestly, I don’t know of a viable hypothesis for this increasing variability outside of climate change,” said Victoria Petryshyn, an associate professor of environmental studies at the University of Southern California, who grew up in Ohio.

In summer, systems are burdened by constant air-conditioning use during periods of extreme heat and humidity. In winter, frigid air masses resulting from disruptions to the jet stream can boost demand for heat and “cause extra strain on the grid if natural-gas lines freeze,” Petryshyn said.

“All the weather becomes supercharged,” Petryshyn said. “We can all expect stronger storms, stronger winds, and more frequent extreme weather that threatens grid stability.”

FirstEnergy has a long history of obstructing measures that would both reduce greenhouse gas emissions and alleviate stress on the power grid.

In February 2024, the company abandoned its interim 2030 goals for cutting greenhouse gas emissions and said it would continue running two West Virginia coal plants. Before that, FirstEnergy backed plans to weaken Ohio’s energy-efficiency goals. And during the first Trump administration, the company urged the Department of Energy to use emergency powers to keep unprofitable coal and nuclear plants running.

FirstEnergy also spent roughly $60 million on efforts to get lawmakers to pass and protect House Bill 6, the law at the heart of Ohio’s largest utility corruption scandal. HB 6’s nuclear and coal bailouts have since been repealed, but the state’s clean-energy standards remain gutted.

Meanwhile, regulators have let FirstEnergy’s utilities charge customers millions of dollars for grid modernization, “which are supposed to support the utility’s ability to adapt and improve the electric grid to rigging challenges from climate change,” said Karin Nordstrom, a clean-energy attorney with the Ohio Environmental Council.

“However, FirstEnergy has not provided the same investment in energy-efficiency programs, which can help manage rising demand at lower cost than expensive capital investment,” Nordstrom said. FirstEnergy should fully exhaust those tools and customer-funded grid-modernization investments before regulators relax the company’s requirements, she added.

Limited transparency makes FirstEnergy’s plan even more problematic, according to Shay Banton, a regulatory program engineer and energy justice policy advocate for the Interstate Renewable Energy Council. Earlier this year, Banton reported on grid disparities in FirstEnergy’s service territories that leave some areas more prone to outages.

“It feels too early for them to request leniency without proposing or implementing more comprehensive mitigations based on a detailed understanding of the root cause,” Banton said.

It’s also likely that FirstEnergy’s rate increase of nearly $76 million for Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co.’s roughly 745,000 customers, approved on Nov. 19, already accounts for some weather-related factors. This summer, spokesperson Hannah Catlett told Canary Media that “the Illuminating Co. service territory generally sees bigger storm impacts” than areas served by FirstEnergy’s other Ohio utilities.

“Our request to adjust the reliability standards is not a step back in our commitment,” Catlett told Canary Media this fall. “We are confident in the progress underway and remain focused on improving reliability through continued investment in the communities we are privileged to serve.”

But fundamentally, additional leeway for weather variation is unnecessary, said Ashley Brown, a former Ohio utility commissioner and former executive director of the Harvard Electricity Policy Group. Averaging utility performance over several years — the way most regulators do as part of setting reliability standards — should already account for that.

“In fact, the standard should always be going up,” Brown added. “You should expect more productivity from the company.”

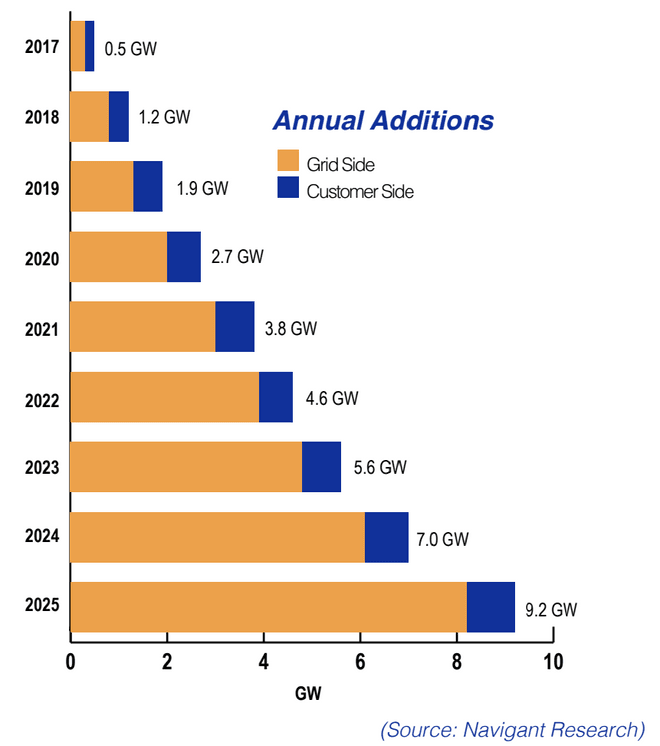

In 2017, the early leaders in energy storage made an audacious bet: 35 gigawatts of the new grid technology would be installed in the United States by 2025.

That goal sounded improbable even to some who believed that storage was on a growth trajectory. A smattering of independent developers and utilities had managed to install just 500 megawatts of batteries nationwide, equivalent to one good-size gas-fired power plant. Building 35 gigawatts would entail 70-fold growth in just eight years.

The number didn’t come out of thin air, though. The Energy Storage Association worked with Navigant Research to model scenarios based on a range of assumptions, recalled Praveen Kathpal, then chair of the ESA board of directors. The association decided to run with the most aggressive of the defensible scenarios in its November 2017 report.

In 2021, ESA agreed to merge with the American Clean Power Association and ceased to exist. But, somehow, its boast proved not self-aggrandizing but prophetic.

The U.S. crossed the threshold of 35 gigawatts of battery installations this July and then passed 40 gigawatts in the third quarter, according to data from the American Clean Power Association. The group of vendors, developers, and installers who just eight years ago stood at the margins of the power industry is now second only to solar developers in gigawatts built per year. Storage capacity outnumbers gas power in the queues for future grid additions by a factor of 6.5, according to data compiled by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

“Storage has become the dominant form of new power addition,” Kathpal said. “I think it’s fair to say that batteries are how America does capacity.”

Back in 2017, I was covering the young storage industry for an outlet called Greentech Media, a beat that was complicated by how little was happening. There was much to write about the “enormous potential” of energy storage to make the grid more reliable and affordable, but it required caveats like “if states change their grid regulations to allow this new technology to compete fairly on its merits, yada yada yada.”

Those batteries that did get built in 2017 look tiny by today’s standards. The locally owned utility cooperative in Kauai built a trailblazing 13-megawatt/52-megawatt-hour battery, the first such utility-scale system designed to sit alongside a solar power plant. And 2017 saw the tail end of the Aliso Canyon procurement, a foundational trial for the storage industry in which developers built a series of batteries in Southern California in just a handful of months to shore up the grid after a record-busting gas leak — adding up to about 100 megawatts.

“You saw green shoots of a lot of where the industry has gone,” said Kathpal.

California passed a law creating a storage mandate in 2010, then found a pressing need for the technology to neutralize the threat of summertime power shortages. Kauai’s small island grid quickly hit a saturation point with daytime solar, so the utility wanted a battery to shift that clean power into the nighttime. These installations weren’t research projects; they were solving real grid problems. But they were few and far in between.

Kathpal recalled one moment that encapsulated the storage industry’s early lean era. At the time, he was developing storage projects for the independent power producer AES. One night around midnight, he parked a rented Camry off a dirt road and pointed a flashlight through a sheet of rain. It was his last stop on a trip to evaluate potential lease sites for grid storage ahead of a utility procurement — looking at available space, proximity to the grid, and stormwater characteristics. But once the utility saw the bids, it decided not to install any batteries after all.

“The storage market is built not only from Navigant reports but also from moments like that,” he said. “We had to lose a lot of projects before we started winning.”

Now that same utility is putting out a call for storage near its substations — exactly the kind of setting Kathpal had toured in the rain all those years ago.

Indeed, many of the projects connected to the grid this year started with developers anticipating future grid needs and putting money on the line for storage back around the time ESA was formulating its big goal, said Aaron Zubaty, CEO of early storage developer Eolian.

“Eolian began developing projects around major metro areas in the western U.S. starting in 2016 and putting the queue positions in that then became operational in 2025,” Zubaty said. The 200-megawatt Seaside battery site at a substation in Portland, Oregon, is one example.

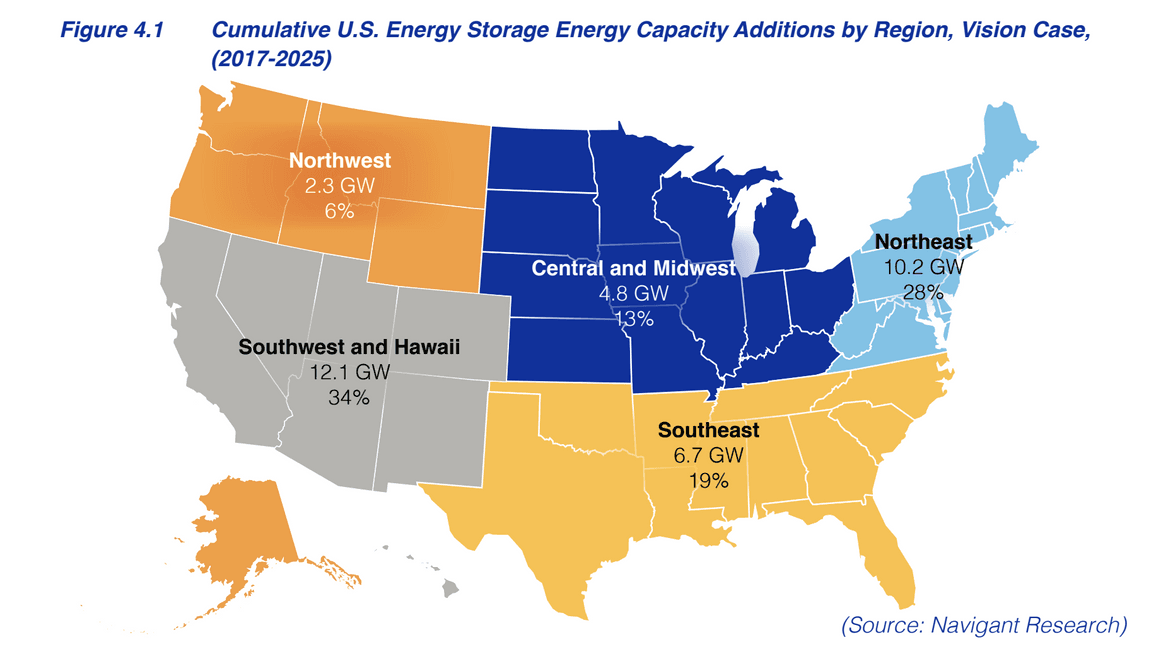

Though the storage industry pioneers somehow nailed the 35-gigawatt goal, market growth defied their expectations in several important ways.

ESA had expected more of a steady ramp to the 35 gigawatts, said Kelly Speakes-Backman, who served as its chief executive officer from 2017 to 2021. But the storage market ran into plenty of false starts, such as when states passed mandates to install batteries but never enforced them, and when federal regulators ordered wholesale markets to incorporate storage but regional implementation dragged on for years.

The ESA report predicted that 2018 deployments would cross the 1-gigawatt threshold, which didn’t actually happen until 2020. But real installations significantly outpaced the expected numbers in the run-up to 2025. The group hoped to hit 9.2 gigawatts installed this year, and instead the industry is on track to deliver 15 gigawatts.

“Once it hit, it really hit,” Speakes-Backman said.

The regional breakdown of storage growth didn’t play out as ESA expected, either. The analysis anticipated that the Northeast would install more than 10 gigawatts, nearly as much as the Southwest (including California and Hawaii); after all, it noted, New England states had passed “aggressive greenhouse gas reduction policies.”

In fact, the Northeast has done exceedingly little to build large-scale storage. (Zubaty told me that “largely dysfunctional power markets combined with utilities that have excessive regulatory capture” thwarted many good battery projects there.)

But other regions surpassed ESA’s expectations. California, Texas, and Arizona alone hold roughly 80% of all U.S. battery storage capacity. This lopsided concentration of storage could be seen as a weakness of the industry. Noah Roberts, executive director of the recently formed Energy Storage Coalition, which advocates for storage in federal arenas, said the pattern reflects how storage has sprung up in spots that suffer acute grid stress.

“Where energy storage has been deployed to date, it is and has been concentrated in areas that have had the greatest reliability need,” he said. “That is Texas and California, where in the early 2020s there were blackouts or brownouts that were quite significant.”

Now, Roberts said, other regions can look at California and Texas for empirical data on how the storage influx has helped reliability while lowering grid costs, for instance by avoiding power scarcity during heat waves and pushing down peak prices. “We’re really seeing the broadening of the geographic footprint of energy storage deployment,” he said, to regions like the Midwest and the mid-Atlantic, which are grappling with unanticipated load growth.

Indeed, the ESA did not foresee the artificial intelligence boom sending power demand through the roof. Instead, its report predicted, “Electrified transportation will likely provide the largest source of new system load.” Now the storage industry has emerged as the biggest player in constructing firm, on-demand power plants, at the exact time that rapid power construction has become the key limiting factor in the AI arms race.

The storage market outdid expectations in one other major way. In 2017 the storage industry was intently focused on getting batteries installed, not so much on where they came from. Since then, bipartisan sentiment has shifted from unfettered global trade to a distinct preference for American manufacturing. The U.S. has made batteries for electric vehicles for years now, but the lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries favored for grid storage have come almost exclusively from China. Now manufacturers are opening domestic cell production for grid storage, just in time for new rules that constrain federal tax credits for battery projects with too much material from China.

LG Energy Solution opened a factory to produce battery cells for grid storage in Michigan this summer that is capable of producing up to 16.5 gigawatt-hours at full capacity; the company expects to raise its North America capacity to 40 gigawatt-hours by the end of 2026. “All of our projects integrated before 2022 combined are smaller than some of our newer individual projects,” noted Tristan Doherty, chief product officer of LG Energy Solution subsidiary Vertech, which focuses on grid batteries.

Tesla is opening domestic LFP battery fabrication in 2026. Fluence announced the first shipment of its “domestically manufactured energy storage system” in September. Newcomers with novel chemistries for longer-duration storage are joining the fray, such as Form Energy and Eos Energy, both of which operate factories outside Pittsburgh.

“By the end of next year, we anticipate reaching the milestone of producing as many domestic energy storage battery cells as we need for demand,” Roberts said. “That is a pretty miraculous story that not many industries have the ability to say they’re able to accomplish.”

The storage industry was vindicated in stretching its aspirations beyond what many thought was possible. Those early adopters knew their technology was valuable, but even they didn’t guess how it would connect with the generational forces reshaping the U.S. economy, from AI to the onshoring of industry.

A clarification was made on Dec. 4, 2025: This story has been updated to reflect that LG Energy Solution’s goal to reach 40 GWh of battery-manufacturing capacity is for North America as a whole, not just for the company’s Michigan plant.

Big companies have spent years pushing Georgia to let them find and pay for new clean energy to add to the grid, in the hopes that they could then get data centers and other power-hungry facilities online faster.

Now, that concept is tantalizingly close to becoming a reality, with regulators, utility Georgia Power, and others hammering out the details of a program that could be finalized sometime next year. If approved, the framework could not only benefit companies but also reduce the need for a massive buildout of gas-fired plants that Georgia Power is planning to satiate the artificial intelligence boom.

Today, utilities are responsible for bringing the vast majority of new power projects online in the state. But over the past two years, the Clean Energy Buyers Association has negotiated to secure a commitment from Georgia Power that “will, for the first time, allow commercial and industrial customers to bring clean energy projects to the utility’s system,” said Katie Southworth, the deputy director for market and policy innovation in the South and Southeast at the trade group, which includes major hyperscalers like Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft.

The terms of the commitment were first sketched out in a letter agreement between Georgia Power and CEBA last year and then codified in a July settlement agreement between the utility, staff at the Georgia Public Service Commission, and other stakeholders that cemented the utility’s long-term integrated resource plan.

The “customer-identified resource” (CIR) option will allow hyperscalers and other big commercial and industrial customers to secure gigawatts of solar, batteries, and other energy resources on their own, not just through the utility.

Letting data centers procure their own energy resources could solve a lot of problems for utilities — like the risk of sticking their customers with the cost of building power plants that may be unneeded if the AI boom goes bust. That’s a real concern for Georgia Power, which plans to spend more than $15 billion to build 10 gigawatts of new gas plants and batteries by 2031. This move could dramatically increase customers’ bills and is almost entirely motivated by gigantic — yet highly uncertain — projections of how much energy that data centers will need.

The tech giants behind most of those data centers could also benefit from being able to track down their own clean energy. The carbon-free resources would not only help in meeting hyperscalers’ aggressive climate targets; they are also likely to be cheaper and faster to build than gas plants, which face yearslong backlogs and rising costs.

The CIR option isn’t a done deal yet. Once Georgia Power, the Public Service Commission, and others work out how the program will function, the utility will file a final version in a separate docket next year.

And the plan put forth by Georgia Power this summer lacks some key features that data center companies want. A big point of contention is that it doesn’t credit the solar and batteries that customers procure as a way to meet future peaks in power demand — the same peaks Georgia Power uses to justify its gas-plant buildout.

But as it stands, CEBA sees “the approved CIR framework as a meaningful step toward the ‘bring-your-own clean energy’ model,” Southworth said — a model that goes by the catchy acronym BYONCE in clean-energy social media circles.

The CIR option is technically an addition to Georgia Power’s existing Clean and Renewable Energy Subscription (CARES) program, which requires the utility to secure up to 4 gigawatts of new renewable resources by 2035. CARES is a more standard “green tariff” program that leaves the utility in control of contracting for resources and making them available to customers under set terms, Southworth explained.

Under the CIR option, by contrast, large customers will be able to seek out their own projects directly with a developer and the utility. Georgia Power will analyze the projects and subject them to tests to establish whether they are cost-effective. Once projects are approved by Georgia Power, built, and online, customers can take credit for the power generated, both on their energy bills and in the form of renewable energy certificates. Georgia Power’s current plan allows the procurement of up to 3 gigawatts of customer-identified resources through 2035.

Letting big companies contract their own clean power is far from a new idea. Since 2014, corporate clean-energy procurements have surpassed 100 gigawatts in the United States, equal to 41% of all clean energy added to the nation’s grid over that time, according to CEBA. Tech giants have made up the lion’s share of that growth and have continued to add more capacity in 2025, despite the headwinds created by the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress.

But most of that investment has happened in parts of the country that operate under competitive energy markets, in which independent developers can build power plants and solar, wind, and battery farms. The Southeast lacks these markets, leaving large, vertically integrated utilities like Georgia Power in control of what gets built. Perhaps not coincidentally, Southeast utilities also have some of the country’s biggest gas-plant expansion plans.

A lot of clean energy projects could use a boost from power-hungry companies. According to the latest data from the Southern Energy Renewable Association trade group, more than 20 gigawatts of solar, battery, and hybrid solar-battery projects are now seeking grid interconnection in Georgia.

“The idea that a large customer can buy down the cost of a clean energy resource to make sure it’s brought onto the grid to benefit them and everybody else, because that’s of value to them — that’s theoretically a great concept,” said Jennifer Whitfield, senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, a nonprofit that’s pushing Georgia regulators to find cleaner, lower-cost alternatives to Georgia Power’s proposed gas-plant expansion. “We’re very supportive of the process because it has the potential to be a great asset to everyone else on the grid.”

Isabella Ariza, staff attorney at the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal Campaign, said CEBA deserves credit for working to secure this option for big customers in Georgia. In fact, she identified it as one of the rare bright spots offsetting a series of decisions from Georgia Power and the Public Service Commission that environmental and consumer advocates fear will raise energy costs and climate pollution.

“They’re proposing something that makes total sense and would help some companies be able to say ‘We’re powering our stuff with 100% clean energy,’” Ariza said of the CIR option. That’s particularly important at a time when many hyperscalers are backing away from their clean energy targets in their hunt for power for AI data centers, she noted.

Despite those benefits, the CIR framework’s omissions are substantial enough that CEBA did not join stakeholders like Walmart, the Georgia Association of Manufacturers, and the Southern Renewable Energy Association trade groups in signing on to it.

CEBA wanted companies to be able to procure a full range of carbon-free generation resources — such as geothermal and small modular nuclear reactors — rather than just renewable energy and renewables paired with batteries. The trade group also sought a pathway for customers to bring projects forward on a rolling basis more quickly than the current settlement agreement would allow.

But one of the biggest issues CEBA has with the current CIR plan is that it “does not recognize the full capacity value of customer-funded clean, firm resources to the grid,” Southworth said. Capacity value is a measure of how power plants, batteries, and other resources meet peak power demands during the handful of hours per year that determine how much generation and grid infrastructure utilities need to build.

That’s a significant gap. If the resources that big customers secure under the CIR aren’t considered part of the solution to this challenge — if their capacity value isn’t factored in — they may not be able to reduce Georgia Power’s need for gigawatts of gas-fired power plants, which are the traditional utility backstop for ensuring adequate energy supplies.

This would be bad for Georgia Power customers at large, who would end up paying for more gas plants than are actually needed after the data centers driving up power demand secure their own resources instead. It could also saddle data centers and other big customers with growing capacity-related costs that their self-secured projects could otherwise help reduce.

“A well-designed CIR program that recognizes the capacity value of customer-funded clean resources is a win-win-win for large customers, Georgia Power, and all ratepayers,” Southworth said. “Participating customers pay the incremental cost of new clean, firm projects; the utility gets capacity it can count on; and nonparticipating customers benefit from a more diverse, less gas-dependent resource mix without taking on the full cost or fuel price risk of those projects.”

CEBA has ideas for how Georgia Power could financially compensate customers for the capacity value of the resources that they procure. The utility already calculates “avoided capacity values” for the renewable energy, battery, and fossil-fueled resources it brings to the table in its requests for proposals. Georgia Power could provide a capacity credit of similar value to subscribing customers for the projects they procure.

CEBA will “continue to work with the company and commission staff,” Southworth said. Her group sees Georgia Power’s long-term plan approved this summer “as establishing the floor, not the ceiling, for what CIR can become.”

A big shift at the Public Service Commission could lay the groundwork for a reassessment of the program. Last month, Georgia voters elected two Democratic challengers — health care consultant Alicia Johnson and clean-energy advocate Peter Hubbard — to replace Republican incumbents Tim Echols and Fitz Johnson.

The two new commissioners have both pledged to tackle high and rising electricity costs for Georgia Power residential customers. Across the country, utilities and regulators are striving to force data center developers to take on the costs they’re imposing on power grids, rather than foisting them on everyday utility customers.

“Capacity is still an open question” that the Public Service Commission can take up as it decides on the CIR option, said Whitfield of the Southern Environmental Law Center. “Georgia Power is certainly on record that they don’t prefer it to be accredited, which makes sense for them. They want to build more and profit more,” as a regulated utility that earns guaranteed profits on its capital investments. “But that is going to be very much a live issue.”

Since spring of last year, North Carolina’s largest utility has been testing whether household batteries can help the electric grid in times of need — and now the company wants to roll out the plan to businesses, local governments, and nonprofits, too.

Duke Energy has already paid hundreds of North Carolinians to let it tap power from their home storage systems when electricity demand is highest. It’s Duke’s first foray into running a “virtual power plant,” in which the company manages electricity produced and stored by consumers, much as it would control generation from its own facilities.

In September, the utility proposed a similar model for its nonresidential customers, asserting that the scheme will save money by shrinking the need for new power plants and expensive upgrades to the grid. The recognition signals a way forward for distributed renewable energy and storage as state and national politicians back away from the clean energy transition.

The initiative now needs approval from the five-member North Carolina Utilities Commission, where the virtual-power-plant model has faced some skepticism. But the apparent merits of Duke’s plan, which has broad backing, may be too enticing for commissioners to ignore — especially when the state is grappling with rising rates and voracious demand from data centers and other heavy electricity users.

“In an era of massive load growth, something that should lower costs to customers while helping meet peak demand — to me, it’s an absolute no-brainer,” said Ethan Blumenthal, regulatory counsel for the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, an advocacy group. “I’m hopeful that [regulators] see it the same way.”

Duke’s trial residential battery incentives grew out of a compromise with rooftop solar installers. Like many investor-owned utilities around the country, the company sought to lower bill credits for the electrons that solar owners add to the grid. When the solar industry and clean energy advocates fought back, the scheme dubbed PowerPair was born.

The test program provides rebates of up to $9,000 for a battery paired with rooftop photovoltaic panels. It’s capped at roughly 6,000 participants, or however many it takes to reach a limit of 60 megawatts of solar. Half of the households agree to let Duke access their batteries 30 to 36 times each year, earning an extra $37 per month on average; the other half enroll in electric rates that discourage use when demand peaks.

The incentives have been crucial for rooftop solar installers, who’ve faced a torrent of policy and macroeconomic headwinds this year, and they’ve proved vital for customers who couldn’t otherwise afford the up-front costs of installing cheap, clean energy.

But the PowerPair enrollees already make up 30 megawatts in one of Duke’s two North Carolina utility territories and could hit their limit in the central part of the state early next year, leaving both consumers and the rooftop solar industry anxious about what’s next.

Duke’s latest proposal for nonresidential customers — which, unlike the PowerPair test, would be permanent — is one answer.

The proposed program is similar to PowerPair in that it’s born of compromise: Last summer, the state-sanctioned customer advocate, clean energy companies, and others agreed to drop their objections to Duke’s carbon-reduction plan under several conditions, including that the utility develop incentives for battery storage for commercial and industrial customers. The Utilities Commission later blessed the deal.

“This was pursuant to the settlement in last year’s carbon plan,” said Blumenthal, “so it’s been a long time coming.”

While many industry and nonprofit insiders refer to the scheme as “Commercial PowerPair,” its official title is the Non-Residential Storage Demand Response Program.

That name reflects the incentives’ focus on storage, with solar as only a minor factor: Duke wants to offer businesses, local governments, and nonprofits $120 per kilowatt of battery capacity installed on its own and just $30 more if it’s paired with photovoltaics.

The maximum up-front inducement of $150 per storage kilowatt is much less than the $360 per kilowatt offered under PowerPair. But more significant for nonresidential customers could be monthly bill credits: about $250 for a 100-kilowatt battery that could be tapped 36 times a year, plus extra if the battery is actually discharged.

Unlike households participating in PowerPair, which must install solar and storage at the same time to get rebates, nonresidential customers can also get the incentives for adding a battery to pair with existing solar arrays.

“That could be very important for municipalities around North Carolina that have already installed a very significant amount of solar, but very little of that is paired with battery storage,” said Blumenthal.

Duke has high hopes for the program, projecting some 500 customers to enroll. Five years in, the resulting 26 megawatts of battery storage would help it avoid building nearly 28 megawatts of new power plants to meet peak demand, saving over $13.6 million. That’s significantly more than the cost of providing and administering the incentives, which Duke places at nearly $11.8 million.

“The Program provides a source of cost-effective capacity that the Company’s system operators can use at their discretion in situations to deliver economic benefits for all customers,” Duke said in its September filing to regulators. “Importantly, the Company received positive feedback from its customers … when sharing the details of the Program.”

Indeed, the proposal has been met with support not just from the Sustainable Energy Association and other clean energy groups but also organizations like the North Carolina Justice Center, which advocates for low-income households. It earned praise from local governments represented by the Southeast Sustainability Directors Network and conditional support from the state-sanctioned customer advocate, known as Public Staff, too.

The good vibes continued last week, when Duke responded positively to detailed suggestions from these parties on how to improve the program. That included a request from Public Staff that the company raise the per-customer limit on battery capacity to align with the maximum amount of solar that a business or other nonresidential consumer can connect to the grid, which is currently 5 megawatts.

“Larger batteries sited at larger customer sites can help provide more significant system benefits and can reduce the need for incremental utility-owned energy storage installed at all ratepayers’ expense,” the agency told regulators in its November comments. It recommends a cap tied to a customer’s peak demand; for example, a business that consumes more energy at once should get incentives for a bigger battery. Duke agreed in its Dec. 5 comments, calling that limit “reasonable.”

Still, questions remain about how to make the incentives most impactful.

Public Staff, for instance, believes Duke should increase its monthly payment to customers for keeping their batteries charged and ready to deploy. This “capacity credit” is now set at $3.50 per kilowatt but effectively reduced to $2.48, because the utility assumes that a percentage of users won’t properly maintain their systems, based on its experience with households. The company calls that a “capability factor,” but the agency dubs it “collective punishment” for all customers and says it should be eliminated or recalibrated for “more sophisticated” nonresidential participants.

Raleigh, North Carolina–based 8MSolar, a member of the Sustainable Energy Association, is among the many installers that have been eagerly anticipating Duke’s proposal.

The program on its own likely won’t “move the needle unless the incentives get bumped up,” said Bryce Bruncati, the company’s director of sales. However, the scheme could tip the scales for large customers when stacked on top of two federal tax opportunities: a 30% incentive available through the end of 2027 and a deduction tied to the depreciation value of the system — up to 100% thanks to the Republican budget law passed this summer.

“The combined three could really have a big impact for small- to medium-sized commercial projects,” Bruncati said. The Duke program would represent “a little bit of icing on the cake.”

Whatever their size and design, the fate of the incentives rests entirely with the Utilities Commission, now that the final round of comments from Duke and other stakeholders is in. There’s no timeline for a decision.

At least one commissioner, Tommy Tucker, has voiced skepticism about leveraging customer-owned equipment to serve the grid at large. “I’m not a big fan of the [demand-side management] or virtual power plants because you’re dependent upon somebody else,” the former Republican state senator said at a recent hearing, albeit one not connected to the Duke program.

Still, Blumenthal waxes optimistic. After all, Tucker and three other current members of the commission are among those who ruled last year that Duke should present the new incentive program.

“They seem to recognize there is value to distributed batteries being added to the grid,” Blumenthal said. “The fact that [the proposal] is cost-effective is key because the idea is, the more of it you do, the more savings there are.”

Two corrections were made on Dec. 10, 2025: This story originally misstated the number of times a year that Duke can tap a PowerPair participant’s battery; it is 30 to 36 times a year, not 18. The story also originally misstated the enrollment Duke expects for the nonresidential program; the utility expects 26 megawatts of batteries, not 26,000 customer participants.

President Donald Trump has made it his mission to banish offshore wind farms from America. He has derided wind energy as unreliable and expensive while freezing permitting and halting projects already under construction.

Yet a new report suggests that the president’s moves could be working against grid reliability in key parts of the country. Along the Northeast and mid-Atlantic regions, offshore wind can play a critical role in keeping the lights on year-round, especially through the winter, according to a study published this month by New York City–based consultancy Charles River Associates.

Trump’s attacks on offshore wind and other renewable sectors come amid dire challenges for the nation’s power system. The world’s wealthiest companies are building power-hungry data centers as grid infrastructure ages and households’ energy bills skyrocket. The White House itself has declared an “energy emergency,” which it’s using to push for more fossil-gas, coal, and nuclear power plants.

But offshore wind is well suited to “meeting the moment,” in part because gas plants are reliable in the summer but can buckle under winter weather, according to the study. Ocean winds in the Northeast are at their strongest and steadiest in winter months, making turbines there a way to boost the reliability of power grids connected to underperforming gas plants.

Oliver Stover, a coauthor of the study, called offshore wind farms a “near-term solution,” saying that turbines at sea and gas plants on land complement each other throughout the Northeast’s changing seasons: “They’re stronger together.”

Stover explained that if grid reliability is the goal, it makes sense for planned offshore wind farms to reach completion. Those projects will help regional grids burdened by extreme winter weather and data-center demands “buy time” as more infrastructure is built.

“Every megawatt is a good megawatt,” he said.

The periods in which offshore wind performs best also align with the time of increasing grid strain: winter mornings and evenings, when people tend to crank up the heat. While peak electricity demand has historically happened during the summer months, it is shifting to these winter moments in many parts of the country, largely due to the mass electrification of space-heating systems.

That means securing power generation during colder months must be, according to Stover, “a priority going forward.”

Stover and his colleagues aren’t the first to underscore the reliability benefits of offshore wind. Other analysts, along with grid operators, have warned that Trump’s efforts to squash certain projects that East Coast states were planning to rely on could raise blackout risks and power bills in the region.

Take Revolution Wind: Trump paused construction of the Rhode Island project in August due to “national security concerns” that a federal judge said were not rooted in “factual findings.” Having won an injunction in court, developer Ørsted eventually resumed construction one month later.

But during the pause and amid mounting uncertainty over the project’s fate, ISO New England — the region’s grid operator — released a statement saying that delaying delivery of power from Revolution Wind “will increase risks to reliability.”

Susan Muller, a senior energy analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists, told Canary Media that if Revolution Wind were killed, the impact would be most acutely felt in winter months. That’s when the region’s limited supply of fossil gas is stretched even thinner, since the fuel is used for both building heating and power generation.

Losing Revolution Wind’s electricity entirely would have cost New England consumers about $500 million a year, according to Abe Silverman, a research scholar at Johns Hopkins University. His estimation was based on the value that the offshore project had secured in ISO New England’s forward capacity market as well as its potential to supplant costlier power plants used during grid emergencies, like snowstorms.

“We don’t need a bunch of fancy studies to tell us that these units are needed for reliability,” Silverman told Canary Media in September during Revolution Wind’s government-ordered pause.

In Virginia, the world’s data-center capital, America’s largest offshore wind farm is slated to start generating power in March 2026. Trump has not yet targeted the 2.6-gigawatt project, but if it doesn’t come online as planned, the mid-Atlantic grid region run by PJM Interconnection would be less reliable and have higher electricity costs, this month’s study says.

In a large swath of the Mid-Atlantic region, offshore wind has one of the highest “resource-adequacy” scores among energy types, according to the study. In other words, when it comes to lowering the probability of blackouts there, offshore wind outcompetes all other types of renewable energy — and is even on par with the most efficient gas-fired power plants.

But the sector is not without its issues, Stover emphasized. Even before Trump’s anti-wind policies made investors skittish and permits no longer guaranteed, construction costs had been ballooning for years, given supply chain issues and inflation.

Offshore wind farms are also, by nature, megaprojects that come with inherent logistical hurdles. Just last month, New York’s Empire Wind lost the turbine-construction vessel it was banking on, due to a skirmish between two shipbuilding companies. Only a handful of boats in the world are capable of doing that kind of work.

The report’s conclusions stand in stark contrast to rhetoric coming from top officials implementing Trump’s war on offshore wind. The sector was just taking off in the U.S. when the president was inaugurated in January, with the first commercial-scale project coming online last year and five more arrays now under construction.

“Under this administration, there is not a future for offshore wind because it is too expensive and not reliable enough,” Doug Burgum, secretary of the Interior Department, told an audience in September at a fossil-gas industry conference in Italy.

Burgum’s statements mirror some of Trump’s favorite talking points that have long misled the public about the risks of wind power. In September, Trump told the United Nations General Assembly in a speech that “windmills are so pathetic and bad” because of their unreliability, falsely claiming that wind power is “the most expensive energy ever conceived.”

The grid does not automatically face problems when “the wind doesn’t blow,” as Trump falsely claimed at the United Nations. Grid operators routinely handle the intermittent nature of power generation from multiple sources — whether it be solar, gas, or wind turbines — through grid-management techniques and, increasingly, battery storage.

Trump is wrong about costs, too.

While offshore wind energy is currently expensive, nuclear energy — a sector the Trump administration aims to boost — is typically the most expensive type of power.

Globally, power generated from wind turbines in the ocean is comparable to other sectors such as geothermal and coal when it comes to cost-competitiveness. In fact, offshore wind has become more cost-competitive relative to other power types in recent years as the sector has matured in Europe and China, according to the most recent analysis by financial advisory firm Lazard.

But when temperatures plummet, offshore wind power could be a huge cost-saver for many U.S. residents. One analysis found that in New England, if 3.5 gigawatts’ worth of under-construction offshore wind farms had been online, households there could have saved $400 million on power bills last winter. In the coming months, cost savings and reliability will take center stage as Vineyard Wind, the region’s first large-scale offshore wind farm to break ground, feeds the grid for its first full winter season.

Two new battery projects on Virginia’s remote eastern peninsula could signal a growing trend in the clean-energy transition: midsize energy-storage units that are bigger than the home batteries typically paired with rooftop solar, but cheaper and quicker to build than massive utility-scale projects.

The 10-megawatt, four-hour batteries, one each in the tiny towns of Exmore and Tasley, represent this “missing middle,” said Chris Cucci, chief strategy officer for Climate First Bank, which provided $32 million in financing for the two units. Batteries are a critical technology in the shift to renewable energy because they can store wind and solar electrons and discharge them when the sun isn’t shining or breezes die down.

When it comes to energy storage, “we need volume, but we also need speed to market,” Cucci said. “The big projects do move the needle, but they can take a few years to come online.” And in rural Virginia, batteries paired with enormous solar arrays — which can span 100-plus acres — face increasing headwinds, in part over the concern that they’re displacing farmland.

The Exmore and Tasley systems, by contrast, took about a year to permit, broke ground in April, and came online this fall, Cucci said. Sited at two substations 10 miles apart, the batteries occupy about 1 acre each.

Beyond being relatively simple to get up and running, the systems could help ease energy burdens on customers of A&N Electric Cooperative, the nonprofit utility that owns the substations where the batteries are sited, said Harold Patterson, CEO of project developer Patterson Enterprises.

Wait times to link to the larger regional grid, operated by PJM Interconnection, are up to two years. So for now, the batteries will draw power only from the electric co-op, Patterson said. Once they connect to PJM, the batteries will charge when system-wide electricity consumption is down and spot prices are low. Then, the batteries’ owner, Doxa Development, will sell power back when demand is at its peak, creating revenue that will help lower bills for co-op consumers.

“That’s the final step to try to drive down power prices” for residents of Virginia’s Eastern Shore, Patterson said. “Get it online and increase supply in the wholesale marketplace.”

Though the batteries aren’t paired with a specific solar project, they are likely to lap up excess solar electrons on the PJM grid. And since they’ll be discharged during hours of heavy demand, they could help avert the revving up of gas-fired “peaker plants.”

“Peaker plants are smaller power plants that are in closer proximity to the populations they serve, and [they] are traditionally very dirty,” Cucci said. “They’re also economically inefficient to run. Battery storage is cleaner, more efficient, and easier to deploy.”

Gas peaker plants are wasteful partly because of all the energy required to drill and transport the fuel that fires them, said Nate Benforado, senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, a nonprofit legal advocacy group.

“Then you get [the fuel] to your power plant, and you have to burn it,” Benforado said. “And guess what? You only capture a relatively small portion of the potential energy in those carbon molecules.”

Single-cycle peaker plants, the most common type, can go from zero to full power in minutes, much like a jet engine. Their efficiency ranges between 33% and 43%.

“Burning fossil fuels is not an efficient way to generate energy,” Benforado said.

“Leaning into batteries is the way we have to go. They’re efficient on the power side but also on the price side.”

Texas proves the financial case for batteries. The state has its own transmission grid, no monopoly utilities, and no state policies to speed the clean-energy transition. Yet it’s gone from zero to some 12 gigawatts of batteries in five years.

In Virginia, A&N Electric Cooperative isn’t the only nonprofit utility investing in energy storage: The municipal utility in the city of Danville, on the North Carolina border, announced earlier this year that it’s building a second battery project of 11 megawatts. Its first system, a 10.5-megawatt battery, which went online in 2022, is on track to save customers $40 million over two decades, according to Cardinal News.

“You look at Texas, where developers are trying to make money on projects,” said Benforado. “And now you see co-ops and municipalities saying, ‘This can save our customers significant amounts of money.’ That, to me, is very telling about the economics of batteries.”

Those economics are even rosier in light of the federal tax credits available for grid batteries, among the few green incentives to survive the budget bill that congressional Republicans passed this summer. Those credits start phasing down in 2033.

While nonprofit utilities in Virginia aren’t impacted by a 2020 state law that requires investor-owned Dominion Energy and Appalachian Power Co. to decarbonize by 2045 and 2050, respectively, they help show what’s possible for the state.