A first-of-a-kind project underway outside Portland, Oregon, could provide a model for data centers to connect to the grid without driving up utility bills and carbon emissions.

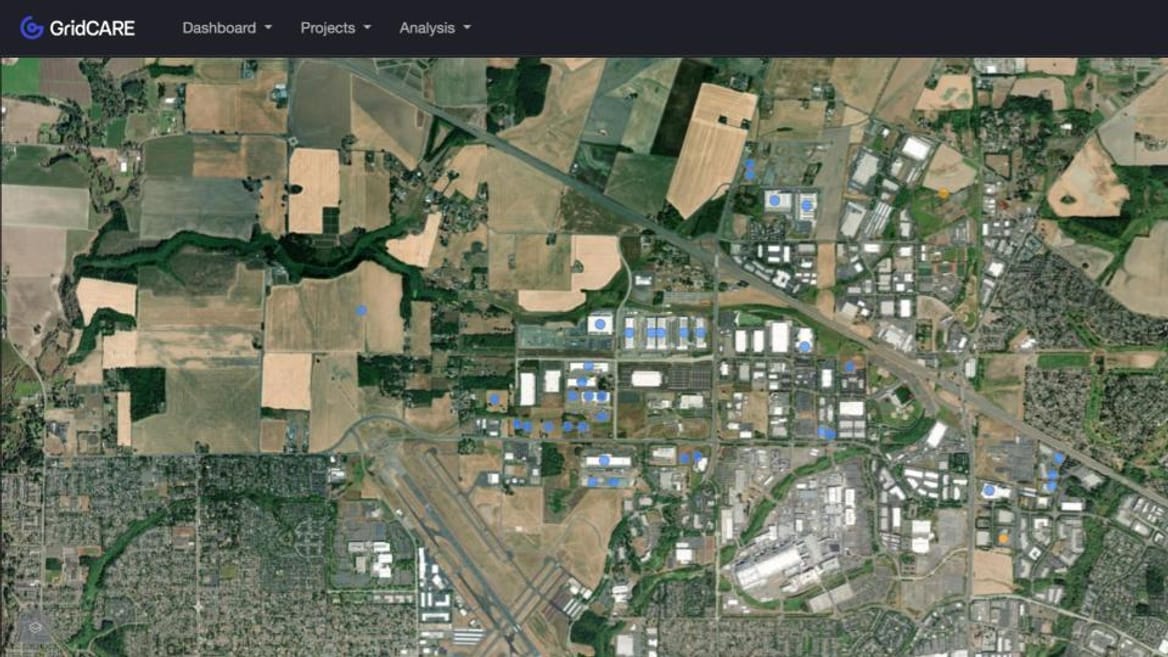

Silicon Valley startup Gridcare launched in May with a promise that its artificial intelligence–powered software can help actualize one of the hottest concepts in the electricity sector: data center flexibility. Last month, it announced the successful use of its software by utility Portland General Electric (PGE) to bring 80 megawatts of data center load online next year in Hillsboro, Oregon.

That’s not a ton of new computing load, considering the gigawatts’ of prospective data center expansions being planned across the country. But as a real-world example of a utility planning around a data center’s commitment to reduce power use during moments of high demand, the project may well be a breakthrough.

“We’ve moved from the theoretical to the practical,” said Larry Bekkedahl, Portland General Electric’s senior vice president of strategy and advanced energy delivery. “This is our first project where that flexibility really comes into play.”

Around the country, utilities are planning massive investments in fossil-fired power plants and grid capacity because of the boom in power demand from data centers. Those spending plans threaten to impose enormous costs on utility customers already struggling to keep up with rising electricity rates.

Data center flexibility agreements could be an elegant solution. If the facilities can ease off their massive power use during the handful of hours per year that they would otherwise overload the grid, they should be able to get connected to the grid sooner — and utilities could defer costly infrastructure upgrades that in some cases include more fossil-fuel power plants.

Other data centers are testing the use of batteries or flexible computing or a combination of both to reduce the burden placed on the grid. But public announcements of flexibility agreements between utilities and data center developers are few and far between — and the technologies that could allow them to become more common are still emerging.

Amit Narayan, Gridcare’s CEO and co-founder, believes PGE’s use of his company’s software may be the “first project of its kind where a utility has been able to accelerate data center expansion at this scale.”

Narayan said the startup also has projects underway with unnamed tech giants and data center developers, as well as with utilities including California’s Pacific Gas & Electric.

“We have these new tools of real-time visibility and dispatchability and control of distributed energy technologies,” Narayan said. “Why do we have to live with the old assumptions of designing around worst-case scenarios?”

In order to understand how PGE and Gridcare’s approach differs from that of other data center flexibility projects around the country, it’s important to grasp the complexity of the problem PGE is trying to solve for its Hillsboro data center cluster.

Hillsboro, a major hub for chipmaker Intel and a terminus for multiple fiber-optic cables connected to Asia, is experiencing “huge demand for data centers in the 50-megawatt to 500-megawatt range,” PGE’s Bekkedahl said. Those data centers are powered by the utility’s transmission grid, which is structured as a network that shares power across multiple interconnected nodes. And existing electricity demand is already pushing that grid close to its operating limits in the Hillsboro area.

Data centers seeking more power from that constrained grid have put PGE in a bind, he said. Under traditional utility planning, the network would have to be scaled up to provide enough power to serve every customer during times of peak demand.

“But there are only a few peak hours, during maybe five to 10 days a year, that we need to meet those peaks,” he said. Building enough transmission to serve them all would take years, cost hundreds of millions of dollars, and yield a grid that’s far bigger than what’s needed most of the time.

Flexibility projects aim to prevent the need to overbuild by reducing the demand peaks that new data centers cause. But PGE can’t make plans based on what a single data center might do. It has to consider the growth plans of all the customers connected to that part of the grid, during every hour of the year, for years into the future — and then also consider the impact on PGE’s regional transmission network and generation fleet.

Human grid planners simply can’t parse through all those variables at once, Bekkedahl said, even with the help of standard planning software.

“That’s where Gridcare came in and helped us model,” he said. Through Gridcare’s software, PGE identified a combination of flexibility opportunities that could allow data centers to add 80 megawatts of additional power use next year, instead of waiting years for traditional grid upgrades, he said.

Narayan is familiar with complex computing challenges. He founded, built, and sold a semiconductor design company called Berkeley Design Automation in the 2000s. Next, he launched Autogrid, a “virtual power plant” software provider that was sold to Schneider Electric, the French energy equipment and services giant, in 2022 and is now part of utility software company Uplight.

Gridcare applies similar computing techniques to model the interactions of lots of power-hungry customers across a dynamic, networked grid, he said.

“You have a major combinatorial-explosion issue here,” Narayan said. “Instead of analyzing one case and one dispatch scenario, which planning teams do — and which is itself very complicated — you have to analyze 200,000-plus scenarios and contingencies.”

Under traditional grid-modeling methods, “that’s typically done in a sequential way, one project and one scenario at a time,” he said. But that’s a highly impractical approach to finding solutions quickly enough to inform utility decision-making.

As Narayan noted, “We have to look at many different projects, each with its impact on ramp and load, over the next five to 10 years. We have to look at very many different scenarios of flexibility. And we have to do it for every hour of the year.”

Recent developments in AI and computing power have made this complex problem solvable: “We’re able to take all the sources of flexibility that may exist, and then examine all the combinations and permutations that exist, and find the lowest-cost way to manage those constraints.”

Not all utilities are ready to rely on flexibility as an alternative to hard grid upgrades. But PGE has been working for years on modernizing its grid operations to support distributed energy and flexibility and bring in real-time data from AI-enabled smart meters, which has given its grid operators confidence in understanding and managing customer-sited energy resources, Bekkedahl said.

With that expertise to back up Gridcare’s revelation of the options at hand, PGE has been able to approach data centers in the Hillsboro area to propose mutually beneficial commitments, he said.

“Those data centers that are willing to work with us, if they’re willing to be flexible, we’ll put them at the top of the queue” for additional power, Bekkedahl said. “For someone who says, ‘Nope, we’re going to want 100 percent,’ well then, we say, ‘You’ll wait for us to build the transmission.’”

At least one data center has already pulled the trigger on a project identified by the collaboration between Gridcare and PGE. Last month, Aligned Data Centers announced plans to work with energy-storage specialist Calibrant Energy to deploy a 31-megawatt/62-megawatt-hour battery across the street from its Hillsboro data center. It’s the first publicly revealed project that’s part of the scope of work enabling the 80 megawatts of additional capacity that PGE will be able to energize next year.

Once it’s turned on sometime next year, that battery will allow Aligned to expand its computing capacity at the data center years faster than it would have been able to by waiting for PGE to upgrade its grid to supply its peak power demand. Aligned didn’t disclose how many megawatts of increased power demand its expansion will cause, a sign of the highly competitive nature of today’s data center market.

Accelerating that “speed to power” has become an overweening obsession of data center operators seeking to meet tech giants’ AI ambitions, and flexibility is increasingly pointed to as the way forward.

A February report from a Duke University team led by researcher Tyler Norris found that the U.S. has nearly 100 gigawatts of existing capacity for data centers that can curtail less than half of their total power use during peak demand events, which occur about 100 hours of the year. Last month, Energy Secretary Chris Wright ordered the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to fast-track a rulemaking process to prioritize such flexible interconnections on U.S. transmission grids.

But data centers can’t afford to invest in batteries like this without clear commitments from utilities that those investments will in fact resolve the grid constraints preventing them from getting online faster.

“This is where PGE was a fantastic partner with us,” said Michael Welch, Aligned’s CTO. “They were able to model these scenarios and understand them with a high degree of accuracy, and provide the greatest impact without wasting capacity. As that came into clarity for us, we were able to work within those constraints.”

Bekkedahl emphasized that PGE is taking its time in its work with Gridcare. While the utility hopes to interconnect 400 megawatts of expanded data center load in Hillsboro by 2029, “we’re not putting on 400 megawatts tomorrow,” he said. “There’s a stepping-stone process here. We want to see it in action before we believe it.”

Nor can PGE completely avoid building more transmission and generation to meet its fast-growing demand for power. “We’re going to have to build out. This is just a bridging strategy,” he said.

But any approach that can increase the amount of electricity that PGE sells without adding exorbitant grid costs should help reduce the impact on customers at large, Bekkedahl said. “Bringing down the peak, and bringing up the overall utilization of the system, makes it more affordable for all customers.”

Xcel Energy’s sprawling Sherco Energy Hub will be among the United States’ biggest solar farms when the last of its three approved phases powers up next year. Soon after, the central Minnesota site could also host one of the Midwest’s biggest battery clusters.

In a Halloween filing, Xcel asked the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission for permission to double its planned battery capacity at Sherco while adding a 200-megawatt fourth phase of solar there and deploying about 136 MW of batteries at a separate site southwest of Minneapolis.

The push to build even more clean energy was spurred by rising electricity demand and the looming phaseout of federal clean-energy tax credits under the Trump administration, which has worked to hamstring renewables while attempting to boost coal and gas generation.

If the commission approves Xcel’s proposal, Sherco would host 910 MW of solar and 600 MW of battery capacity by the end of the decade. At peak production, that would go a long way toward offsetting the output of what Xcel representatives have called the “backbone” of the company’s Upper Midwest generation fleet: the roughly 2,300-MW Sherco coal plant, which shut down its first unit in late 2023 and is set to fully retire in 2030.

George Damian, director of government affairs for Clean Energy Economy MN, said the proposal underscores the growing importance of batteries as the grid shifts away from fossil fuels.

“As demand continues to rise, technologies like battery storage are becoming essential to maintaining reliability while integrating more carbon-free generation,” Damian said.

Xcel regional president Bria Shea agreed, saying in a statement that “[w]e’re making a significant investment in battery storage because we see it as a critical part of Minnesota’s energy future.”

The separate 136-MW Blue Lake project would replace retired fossil-fuel capacity, too, boosting output at what’s now a 332-MW gas peaker plant. Xcel retired Blue Lake’s aging oil-fired units earlier this year, leaving two newer gas units operating and freeing up more than 200 MW of grid interconnection capacity.

Minnesota requires its utilities to procure 100% clean power by 2040 and aims to decarbonize its entire economy by 2050, with ambitious targets for building and transport electrification. Meanwhile, developers have proposed at least a dozen large-scale data center projects around the state, including several in Xcel territory. In December, Xcel executive Ryan Long — then serving in Shea’s role — said the company could absorb 1.3 GW of data center capacity by 2032 without derailing its carbon-free power plan, though he added it may need to extend the life of some gas plants to accommodate the load increase.

In the filing, Xcel said it wants to move quickly to expand its generation capacity while there’s still time to qualify for federal clean-energy tax incentives of 30% or more.

President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act will sunset those incentives several years early, forcing most wind and solar projects to begin construction before July 4, 2026, to qualify for the full value. Energy storage projects qualify for the full credit value through 2033, but Xcel said uncertainty around new foreign-sourcing restrictions taking effect next year increases the urgency to deploy storage soon too.

Xcel says it expects to break ground on the Sherco and Blue Lake battery installations next year and power them up in 2027. It aims to commission the Sherco solar project by 2029.

Rather than contract with independent solar and battery installations in its territory, Xcel wants to build and own all three projects itself. In the filing, it said rules set by Minnesota’s grid operator require company ownership of new energy facilities reusing interconnection rights at retiring power plants. The same filing asks the commission to approve agreements to purchase power from several third-party solar and battery projects that will connect to the grid elsewhere.

John Farrell, the Minneapolis-based codirector of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance and a frequent critic of the monopoly-utility model, said the looming tax-credit cliff creates an unusual circumstance where the need to quickly develop more clean energy cuts against his preference for an open and competitive bidding process that could result in a better deal for electricity customers.

“I am more sympathetic than I would be normally because we are stuck in the regime we’ve got and there’s a lot of money on the table,” he said, referring to the tax credits whose rollback is expected to raise Minnesotans’ electricity bills in the coming years.

To incentivize faster clean-energy deployment ahead of the cliff created by Trump’s megalaw, the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission in August said it would allow projects that meet the deadline for federal tax incentives to also access extended eligibility for state renewable energy credits.

Xcel spokesperson Theo Keith said the utility has “already taken steps to ensure this portfolio of projects will qualify for federal tax credits before they expire.”

But with the North American Electric Reliability Corp. forecasting a “high risk” of capacity shortfalls on the Upper Midwest grid by 2028, there’s a chance that the U.S. Department of Energy issues an emergency order requiring one of the Sherco plant’s two remaining coal units to run past its planned retirement next year, said Allen Gleckner, chief policy officer for Minnesota-based Fresh Energy.

The DOE has already done so for one retiring coal station in the Midwest, Michigan’s 1,420-MW J.H. Campbell plant. Its operator, Consumers Energy, says that order, which runs at least through Nov. 19 and which the DOE says it could extend for much longer, has already cost consumers at least $80 million. It’s unclear whether a similar order at Sherco would affect Xcel’s battery plans, but it would be disruptive to the utility either way, Gleckner said.

“The uncertainty that scenario contemplates is another reason why it would be a terrible idea,” Gleckner said.

Asked if Xcel had reason to expect a DOE emergency order at Sherco and whether that could interfere with its proposed clean-energy deployments there, Keith said only that Xcel is moving ahead with its plans to retire the coal units by 2030.

“We are in regular conversations about Minnesota’s energy future with various stakeholders, including federal, state, and local elected officials,” he said.

When Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont, a Democrat, first nominated Marissa Gillett to the Public Utilities Regulatory Authority in 2019, he praised the “outsider’s perspective” she would bring to the state’s energy challenges. This September, just months after a bruising reconfirmation process, she stepped down, citing a tangle of acrimonious disputes with investor-owned utilities and lawmakers who bristled at her novel approach to regulation and accused her of inappropriate, even unlawful, bias.

Public utility commissions are essential but largely invisible forces regulating and shaping electricity, gas, and water services at the state level. Traditionally, these boards have been thought of as working in tandem with utilities, rarely challenging their proposals and claims. Recently, though, the tides have shifted, as more states and advocacy groups look at ways for commissioners to advance state energy policy.

The need for decisive action from utility commissions is becoming more acute as electricity prices climb almost everywhere in the country and many states push to meet decarbonization goals. The regulatory status quo just doesn’t lend itself to the systemic changes needed to fight these battles.

Gillett has been hailed by some as an exemplar of the assertive regulator, bringing a decidedly proactive sensibility to her work on the Connecticut commission, commonly called PURA. Following her resignation from the board, Gillett sat down for a conversation with Canary Media about what that involved regulation should look like as states face down a crucial moment for consumers and climate alike.

“Regulators need to roll up their sleeves and figure out how to provide continuous, sustained rigorous oversight,” she said.

The traditional model for investor-owned utilities guarantees them a set rate of return on every dollar spent building new distribution lines, upgrading substations, and other such projects. This dynamic has led to criticism that utilities are prone to overspending on infrastructure that might not be in the interest of customers or the environment, for the simple reason that it will bolster their earnings and please their investors.

A key job of leaders like Gillett is to weigh these utility requests against the need for adequate, reliable infrastructure, and the needs of consumers and the state’s energy policy goals. But for too long, critics say, commissioners have functioned more as umpires calling balls and the occasional strike, approving most utility requests.

Before coming to Connecticut, Gillett worked for seven years at the Maryland Public Service Commission, contributing to the development of initiatives including the state’s electric vehicle programs and its offshore wind plan. After a brief stint with the Energy Storage Association, a trade group, she threw her hat in the ring for the Connecticut commissioner position.

Gillett came into the job ready to be the “change agent” the governor said he wanted. Her aim was to reform an entrenched system that had led to some of the country’s highest electricity rates and mixed progress on climate goals — and to move away from the “balls and strikes” mentality that she found unrealistic and limiting.

“I acknowledge you have to make decisions based on the evidence and record in front of you,” she said.

But she was not willing to accept that the only evidence available was what was contained in utility filings and the responses to them. She offered this analogy: If one party came before PURA saying the sky was green, and another argued it was purple, the board should not be forced to choose between those two options.

To dig deeper into the issues before the commission, she assembled a staff of 80 “who are the best in the business and are very passionate about the work,” a group she hopes stays in place despite her departure.

“It is important who sits in the commissioners’ seats, but it’s also important who staffs them,” she said.

Right from the beginning, she and her staff led PURA in several controversial decisions that left utilities and Republican lawmakers claiming she was creating a hostile and uncertain environment for the state’s two major investor-owned utilities — Eversource and United Illuminating — and their shareholders.

After the utilities struggled to restore power following Tropical Storm Isaias in 2020, PURA ordered Eversource to return $28.4 million to customers in the form of bill credits. In 2023, the commission reduced United Illuminating’s requested $123 million rate increase by $100 million. The utility challenged this move in court, but PURA’s decision was upheld.

Gillett argues she always just applied rules that were on the books but rarely enforced. She points to her track record in court cases: Five times utility challenges have made it to the Connecticut Supreme Court, and five times the court supported PURA’s rulings, she said.

“For years we heard in public that I was acting illegally, making decisions that were arbitrary and capricious,” she said. “I was now holding them to standards they had not been held to. I viewed myself as somebody tasked with implementing state policy.”

While the financial penalties and rate reductions Gillett’s PURA imposed garnered headlines, she also made changes that were less widely noticed, with the goal of prepping the grid to handle more renewable energy. Within Gillett’s first year, the board launched the Equitable Modern Grid initiative, a series of investigations into 11 topics, including advanced metering, energy storage, and affordability. The process yielded ongoing action, including a battery incentive for homeowners and businesses and a program to fund pilots trying out innovative grid technologies.

“Considering how slowly regulatory processes usually work, I think designing and launching those programs in that amount of time was very impactful,” Gillett said.

It’s difficult to assess the effect of Gillett’s philosophy on Connecticut’s energy and climate landscape quite yet: Changes to the utility industry are notoriously slow-moving, and the pandemic added an extra level of disruption to her tenure.

Electricity prices remain high there, as they are throughout the entire Northeast, but Gillett leaves behind programs intended to reduce the energy burden on low-income households. During her tenure, the state implemented its first discount electricity rate for such families and launched an outreach program to help disadvantaged households access assistance offerings.

Gillett does not yet have her next move mapped out, but she does have a degree of optimism that utility regulation is evolving toward the sort of goal-driven, engaged model she brought to her time in Connecticut.

More states are already taking seriously the need to seek out “competent, qualified” regulators with a background relevant to the work, she said. She pointed to a Brown University study that found, nationwide, the share of commissioners with previous work on environmental issues grew to 29% in 2020 from 12% in 2000. States like Maine and Colorado have taken steps to direct their utility regulators to consider emissions, equity, and environmental justice when making decisions.

“As electricity affordability becomes more front-and-center, and folks are looking to who is supposed to be watching out for them, there will be a moment when regulators embrace that philosophy more,” she said.

An Indiana utility has come up with an unusual plan for meeting growing power demand from data centers.

Northern Indiana Public Service Co. is launching a spinoff company, GenCo, that is exempt from many of the regulatory proceedings typically required before power plants can be built in the state. The utility, also known as NIPSCO, says that this will allow the new entity to quickly provide the copious amounts of energy that data centers need without pushing excessive costs onto other consumers.

But the move is raising alarm bells for watchdog groups and other critics, who argue that rather than protect consumers, the plan will mainly enrich the utility’s parent company while interfering with market competition and undercutting important regulatory safeguards. It could also set back the state’s clean-energy transition, advocates say.

As regulators around the country wrestle with how to get a lot of power online quickly to serve “hyperscaler” AI data centers, other utilities may be looking at NIPSCO’s “unique arrangement” as “a model for how to maximize profits while meeting new data-center demand,” said Emily Piontek, a regulatory associate at the nonprofit Clean Grid Alliance.

Indiana is attractive to huge data centers because of its cheap land, ample water, special state tax breaks on equipment and energy, and access to both the PJM Interconnection and Midcontinent Independent System Operator regional electric grids. The State Utility Forecasting Group at Purdue University recently predicted that data centers will almost double Indiana’s energy demand by 2035.

NIPSCO highlighted that boom to the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission during the case proceedings to create GenCo. Vincent Parisi, president and CEO of both NIPSCO and GenCo, told regulators about the sheer number of requests the utility has gotten from potential “megaload” customers, generally data centers, seeking hundreds or even thousands of megawatts of electricity.

But it’s a competitive business, with other states and municipalities courting the same data centers. NIPSCO says that providing new power quickly, through GenCo, will be key to securing the deals.

The regulatory commission agreed with this reasoning, writing in its September order approving the GenCo plan, “The evidence shows that megaload customers are sophisticated and have many choices available to them when determining where to make developments.” The commission added that relinquishing its jurisdiction over aspects of GenCo “will enable NIPSCO to support Indiana’s efforts to compete with other states to attract this economic development.”

Nationwide, regulators and advocates have grappled with concerns that residential customers could pick up too much of the tab for new generation built to power data centers, especially if the computing warehouses don’t materialize or don’t use as much power as predicted.

NIPSCO says GenCo will protect customers from such costs since it will be responsible for providing the data centers with power. That means those expenses won’t be rolled into the rates paid by other NIPSCO consumers, the utility says.

But Citizens Action Coalition, the state’s main consumer-advocacy group, argues that the GenCo structure doesn’t really insulate customers from the risks of the data-center market.

If GenCo were to lose money, that could affect the finances and credit rating of parent company NiSource and hence impact NIPSCO’s customers, said Citizens Action Coalition Executive Director Kerwin Olson. And he worries some costs of data-center power infrastructure could still be passed on to residential customers, hidden in an opaque process created specifically for GenCo.

In September, the state regulatory commission exempted GenCo from a host of usual procedures. Chief among them is that GenCo does not have to file a detailed plan when it wants to build or acquire new generation. The commission did not set any minimum standards or requirements regarding how power will be provided to data centers, as advocates had hoped. Instead, the commission will review each proposed contract between NIPSCO and a data center, and the related power purchase agreement between NIPSCO and GenCo.

The Citizens Action Coalition called this case-by-case review process unfair and inefficient, making it too difficult for stakeholders to monitor the situation and submit public comments to the commission.

“Every single time a data center comes online, there’s another case; there’s no minimum criteria or boxes that need to be checked,” said Olson. “I know they’re claiming costs won’t be passed on to ratepayers, but we’ve been around the block. When you have what will likely be confidential special contracts, everything redacted, it’s going to be really challenging for stakeholders to dive into the details to ensure that none of these costs are being passed on.”

NIPSCO declined to answer questions but referred Canary Media to a press release quoting Lloyd Yates, NiSource president and CEO, regarding the regulatory commission’s decision.

“This is an important step forward to position Northern Indiana at the center of a fast-growing, economically essential industry,” Yates said.

The Citizens Action Coalition and the Indiana Office of Utility Consumer Counselor, a state agency tasked with protecting consumers, notified the commission that they plan to appeal the approval of GenCo.

Another major concern of critics is that GenCo will have an unfair competitive advantage over other power producers.

Indiana has a regulated energy market, wherein utilities have the right to serve as monopoly producers and distributors of energy, but regulators must approve how much capacity they build or buy and what they charge customers for the power.

GenCo is largely exempt from this structure, acting more akin to a power producer in a state like Illinois, with a deregulated market. But in Illinois, power producers compete to sell their energy to utilities, whereas GenCo has a guaranteed customer in the form of NIPSCO, and the two sister companies — which share the same parent — set the price NIPSCO will pay GenCo for power.

“The utility affiliate is being treated like an unregulated independent power producer while retaining the guarantee of a monopoly market enjoyed by regulated utilities,” Piontek said. “Essentially, the arrangement insulates GenCo from market forces, and [it] is not subjected to rate regulation. It’s going to be a very profitable arrangement for the parent company and its shareholders … by providing the affiliate with an unearned competitive advantage.”

The Clean Grid Alliance — made up of renewable-energy developers, environmental groups, and other stakeholders — and Takanock, a data-center developer, told regulators in a joint brief that GenCo “turns the federal paradigm which encourages competition … on its head by proposing that GenCo, and only GenCo, provides generation services to NIPSCO to serve its megaload customers.”

In testimony, Takanock founder and CEO Kenneth Davies told regulators about problems his company has had trying to acquire power from NIPSCO for a planned data center. Davies described the NIPSCO-GenCo relationship as “anticompetitive,” and lamented that NIPSCO will not allow new data-center customers to buy power on the open market themselves, as some existing industrial customers are allowed to do. Davies said NIPSCO seems to be “picking and choosing” which data centers to prioritize, and he is worried Takanock could be treated unfairly, since confidential contracts would make it difficult to compare the arrangements other data centers are getting.

Davies and other stakeholders say there are ways for NIPSCO to protect customers from data-center costs without creating a new market entity with an unfair edge.

Takanock and the Clean Grid Alliance, in their filing, criticize GenCo for failing to explore the more common method of pricing tariffs designed specifically for data centers. That’s where a utility makes an agreement with state regulators to treat data centers differently from other customers, ensuring they pay their fair share of costs. Davies described Wyoming regulators’ creation of such a special tariff to serve a Microsoft data center. Davies was Microsoft’s director of renewable-energy strategy and research at the time.

In another example, Citizens Action Coalition reached an agreement last year with utility Indiana Michigan Power and three new data centers, requiring long contracts, exit fees, and other protections to ensure the centers pay the full costs of infrastructure built to serve them, even if they don’t use as much power or operate for as long as expected. The agreement also requires the data centers to pay millions of dollars to support low-income electricity customers with benefits like weatherization.

Advocates point out that Indiana already has a law on the books meant to help utilities more quickly get power online to supply data centers, without sacrificing transparency or relying on a new entity like GenCo. HB 1007, enacted in May, gives utilities an expedited approval process for new generation if they provide information about the impacts on customers, predicted load growth for the next five years, and the potential of grid-enhancing tech to avoid investments in new power plants, among other things.

“NIPSCO decided to ignore 1007 and create what we think is a shell game, a scam, with this unregulated affiliate doing Lord knows what,” said Olson.

The creation of GenCo will likely undermine the clean-energy transition in northern Indiana, advocates say. NIPSCO has already made clear its plans to build lots of natural-gas-fired generation to power data centers, and if this is carried out through GenCo, stakeholders will have little opportunity to weigh in on the implications.

This is a disappointing shift for environmental groups that had praised NIPSCO for plans it announced in 2018 to retire all coal plants within a decade and build out renewables, reducing carbon emissions by 90%.

By contrast, NIPSCO’s 2024 Integrated Resource Plan says that if contracts with data centers are in place, the utility will build over 1,700 megawatts of gas generation by 2030 and another over 2,000 MW by 2035. Already, NIPSCO is seeking an air permit to build 2,300 MW of gas-fired generation at the site of a retiring coal plant, in order to serve data centers.

“GenCo is certainly a concern for the climate, demonstrating that NIPSCO has done a complete strategy reversal on sustainability,” said Ben Inskeep, program director at Citizens Action Coalition. He said the utility’s 2018 resource plan “was groundbreaking for leading the way on a clean-energy transition. Now, they are pursuing a strategy that appears to be 100% natural gas for new data centers, with no additional clean energy to serve the additional load.”

If NIPSCO had to turn to the open market to procure the power that data centers need, Piontek noted, more renewables would likely get built along with the gas-fired generation.

“Clean-energy resources like wind, solar, and energy storage outcompete other resources in speed-to-market and remain the most cost-effective resources available, making them an attractive option for bringing data centers online in Indiana,” Piontek said.

Batteries have quickly become a crucial part of the U.S. electricity grid — and a whole lot more are about to come online.

Over the next five years, the country will build nearly 67 gigawatts’ worth of new utility-scale batteries, per data from research firm BloombergNEF, enough to send almost 284 gigawatt-hours of stored-up electricity back to the grid.

Those are massive figures. Should the forecast bear out, the U.S. will have roughly three times more battery capacity in 2030 than it does now. Such rapid growth is familiar territory for the sector, which jumped from just 1.5 GW of total capacity in 2020 to a whopping 27.3 GW by the end of last year.

The transition to renewable energy — particularly solar — relies on batteries. That’s because communities with lots of solar arrays often generate more power than the grid needs at a particular moment in time. Batteries let these solar-saturated states save that extra energy for later use.

California and Texas, the U.S.’s two leaders on solar, have built the vast majority of the country’s utility-scale storage. Already, the states are reaping the benefits. By spring of 2024, California’s battery fleet had grown large enough to begin displacing some natural-gas use in the evening. Meanwhile, batteries have helped Texas stave off summertime grid emergencies for two years running.

As battery developers propose more, bigger projects, the sector has started to run into some opposition. Just last week, news broke that plans to build New York’s biggest battery on Staten Island fell through following fervent protest from the local community. Fears of battery fires have spread around the country following the massive blaze at California’s Moss Landing facility in January, even though that disaster stemmed from the project’s outdated design.

Still, several broader trends suggest the sector’s growth will continue.

For one, President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act left incentives for battery storage relatively untouched, even as it yanked away tax credits for solar and wind projects. Then there’s the fact that solar is growing steadily around the country, which will eventually create a need for storage in other states just as it has in California and Texas. Most important of all, demand for electricity is surging nationwide — and batteries are among the cheapest and quickest ways to get more capacity onto the grid.

Illinois legislators passed a major energy bill that creates grid-battery and geothermal incentives and a virtual-power-plant program, during the final hours of a fall veto session Thursday.

Advocates and industry sources describe the legislation as the crucial next step in the state’s clean-energy transition, jump-started by 2017 and 2021 laws that created significant solar and wind incentives. The bill’s passage comes as the Trump administration eviscerates federal support for clean energy and as a debate plays out in state legislatures around the country over how best to rein in soaring electricity rates.

The legislation faced substantial pushback, largely because of concerns about the costs imposed on residential and industrial customers to fund the energy-storage incentives. It also faced stiff competition for legislators’ attention during the six-day veto session, as bills related to a transit-funding emergency, a new stadium, and insurance regulation were also on the table.

The state House passed the bill on the second-to-last day of the October veto session, and the state Senate passed it in the final hours on Oct. 30. Gov. JB Pritzker, a Democrat, has pledged to sign the bill.

The Clean and Reliable Grid Affordability Act, or CRGA, calls for the procurement of 3 gigawatts of energy storage by 2030.

The Illinois Power Agency, which procures electricity on behalf of the state’s two major utilities, ComEd and Ameren, estimates that developing and operating the storage will cost $9.7 billion over 20 years. That money will be collected from utility customers through a new charge on their electricity bills. But under the incentive structure, a portion of the revenue earned by the storage companies will go back to consumers. With this factored in, customers will end up paying an estimated $1 billion for the storage.

Meanwhile, energy storage connected to the grid will save those same customers an estimated $13.4 billion over 20 years, since the influx of electricity into “capacity markets” will suppress prices, the Illinois Power Agency predicted. Capacity markets are run by regional grid operators to make sure enough power is available to meet future demand.

Mark Pruitt, an energy consultant who previously led the Illinois Power Agency, said that getting more electricity into capacity markets is urgent because of the AI data centers springing up in the state.

“Is there a way of demonstrating that we’re going to be able to get a benefit for consumers in all of this?” asked Pruitt. “That was an honest concern by many of the policymakers. When do consumers start to see a benefit, and will they see lower costs? I don’t know that prices are coming down; it’s a question of can you slow their rate of increase.”

The credit structure meant to incentivize storage under the bill is already being used as part of the state’s subsidy program to keep existing nuclear plants online, which got started in 2021. At the time, watchdog groups worried the mechanism would cost households money, but the arrangement has actually benefited consumers.

Energy-storage deployment is central to the virtual-power-plant program created by the bill, wherein homes and businesses with batteries can earn revenue by supplying energy to the grid when needed. The bill also, for the first time, makes geothermal eligible for state renewable-energy incentives. And it lifts a decades-old moratorium on the construction of large nuclear plants. The legislature had revised the moratorium in 2023 to allow small modular nuclear reactors to be built, though this technology is still nascent.

Legislators’ approval of CRGA “is a major step toward strengthening Illinois’ power grid and keeping energy costs in check,” said Hannah Flath, climate communications manager of the Illinois Environmental Council, a group of over 100 environmental organizations working on policy and advocacy. “Battery storage represents the next phase of Illinois’ clean-energy buildout, ensuring that clean power is available around the clock.”

The bill was backed by the Illinois Clean Jobs Coalition, made up of clean energy, environmental, and community groups that were instrumental in crafting and passing the 2021 Climate and Equitable Jobs Act. That law built on 2017’s Future Energy Jobs Act, by increasing incentives for renewables and electric vehicles and creating an ambitious clean-energy workforce training program, among other measures.

In February, legislators introduced two separate storage-related bills, one backed by the Clean Jobs Coalition and the other by storage and solar industry groups. They eventually joined forces, pushing together for CRGA.

Opponents — namely, large energy users — argued that storage development should be left to the open market and that customers shouldn’t have to pay for incentives.

“We want an all-of-the-above energy strategy,” said Phillip Golden, chair of Illinois Industrial Energy Consumers, which represents companies that use lots of electricity. “We think battery storage has a role to play; we think renewables have a role to play. What we’re anti is making ratepayers pay for things they don’t need to. Look to Texas: We’ve seen battery-storage developers invest in projects without state procurements.”

Indeed, Texas has seen rapid growth of battery storage, thanks in part to a lack of regulation. But backers of CRGA said it’s too risky to count on companies to build storage if they don’t have certainty of earning revenue.

The debate played out as northern Illinois residents served by ComEd face a serious spike in electricity prices, driven by the high cost of capacity in the PJM Interconnection regional market. CRGA proponents have said that storage on the grid is crucial to mitigate escalating prices, in part because it facilitates more solar deployment; energy from solar can be held in batteries until it’s needed.

“The only way to protect ratepayers and address energy affordability is by investing in solar and storage, the fastest and cheapest energy sources to deploy,” said Andrew Linhares, a senior manager at the Solar Energy Industries Association who focuses on the Midwest. “Energy costs are already set to increase next summer, and they’ll continue to skyrocket every year until Illinois solves its energy supply-and-demand imbalances.”

CRGA backers sought to dispel the myths that they say swirled leading up to and during the veto session, including the fear that companies could get incentives before they even built storage.

“CRGA does not deliver any benefits to storage projects until those projects are online,” said Stephanie Burgos-Veras, senior manager of equity programs at the Coalition for Community Solar Access, made up of businesses and nonprofits nationwide. “This means ratepayers have no up-front cost for the storage program, and that all projects must actively contribute to the grid through stored power and price suppression before they are eligible for incentives. It is an incredibly safe funding model that ensures families and businesses receive risk-free savings.”

Ultimately, backers of CRGA said the bill’s passage shows that a state-level clean-energy transition can still move forward even without federal support.

“This bill isn’t just a rejection of Trump’s anti-climate policies — it’s proof that local and state action can offset those backward policies,” said Flath. “Illinois consumers, our power grid, and our climate will be better protected from price volatility and increasingly extreme weather events because we’re stepping up to fill the gap where the federal government is failing us.”

CEOs of artificial-intelligence companies want to spend hundreds of billions of dollars building their energy-gobbling data centers, but that can’t happen without the necessary electricity supply. And they want to move way faster than electric utilities are used to.

One idea gaining traction is to allow data centers to come online more quickly if they agree to occasionally pull less power from the grid when demand is high, a concept endorsed by none other than Energy Secretary Chris Wright in a rulemaking proposal filed Thursday. The massive computing facilities could accomplish such flexibility with the help of on-site renewables and batteries, but precious few projects using this model have materialized. That’s about to change.

On Wednesday, Aligned Data Centers announced it would pay for a new 31-megawatt/62-megawatt-hour battery alongside a forthcoming data center in the Pacific Northwest. The battery, developed by energy-storage specialist Calibrant Energy in partnership with the local utility, is now entering the construction phase and should be operating sometime next year. The kicker is, this deal will let Aligned get up and running “years earlier than would be possible with traditional utility upgrades,” per the companies.

If the plan works, would-be AI leaders will be jumping all over this battery-first strategy. In fact, many already are, they just haven’t publicly acknowledged it yet.

“There’s so much chatter right now about the potential to use energy storage in this manner to facilitate the connection that large power users want from the grid. But there hadn’t really been evidence of that theory being reality,” said Phil Martin, CEO at Calibrant, which is owned by Macquarie Asset Management. “It is possible, and it is being done — not as a proof of concept in a lab somewhere, but really a commercial project.”

Batteries aren’t, at first glance, a tool well matched to the needs of AI computing.

Lithium-ion chemistries have become quite competitive for short-form activities: First, it was managing second-by-second frequency fluctuations on the grid; now, in places like Australia, California, and Texas, batteries are shifting solar generation to compete with gas plants in the evening when demand rises.

Data centers, though, use energy around the clock — not literally at full blast 24/7, but a lot closer to it than current batteries can keep up with. Data-center developers have chased new gas, hydropower, and an exotic array of nuclear power plants in hopes of feeding the beast. But those options will take several years to come online, if they ever get built. The headlong rush into AI demands nearer-term solutions.

As a lot of exceedingly well-funded firms contemplated this conundrum, some thinkers started focusing on grid flexibility as a way to accelerate the computing-infrastructure buildout. Earlier this year, Duke University researcher Tyler Norris made waves in the AI-energy world with research that found today’s grid could handle quite a lot more data centers if the facilities could simply dial back their consumption for a couple hours at a time during moments of maximum demand.

The Aligned battery offers a concrete example of that kind of research. The utility studied just how big the battery would need to be to compensate for challenges imposed on the local grid by the data center. Aligned and Calibrant had their own calculations, Martin said, “but the validation of that, and the actual specification of that, came out of the interconnection study done on the utility side.”

Due to the local nature of the power constraint, the battery had to be built close to Aligned’s facility; the company ultimately provided the land to host the grid storage installation. In other cases, where a proposed data center runs up against a system-wide capacity constraint, a battery solution could be further away.

Another glimpse of the battery-enabled future came this summer when Redwood Materials, a richly funded battery-recycling startup, unveiled a new business line that repackages old EV batteries to serve data-center demand. The first installation, at Redwood’s campus near Reno, Nevada, fully powered a very small, modular data center using a solar array and a field of former EV battery packs laid out on the desert floor.

Redwood just got its own vote of confidence in that concept: On Thursday, it raised another $350 million from investors including AI-chip leader Nvidia.

Aligned’s commitment to paying for the battery itself could serve as a model of socially responsible AI-infrastructure development.

Some utilities around the country are jumping to build new power plants to support the projected data-center buildout, and charging their regular customers for the investment, hoping the AI titans eventually become paying customers. But this approach risks saddling consumers with unnecessary costs if the AI hubs don’t materialize.

Because Aligned is footing the bill, the utility’s other customers won’t be forced to pay for the data-center firm’s growth ambitions. But, though this one large customer will provide the land and funding, the battery will sit on the utility side of the meter. That means the utility can leverage the tech for other grid uses, like frequency management and capacity, when it’s not maintaining the flow of power to the data center during otherwise scarce hours.

In this case, Martin said, the permitting and buildout could move faster with the battery connecting to the utility grid instead of directly to the data center. In other situations, bigger batteries on the customer side of the meter might make more sense. Calibrant is already working on more and even larger batteries for the AI sector, he added.

“Whereas right now, we think this is unique, I think over a relatively short time horizon it’s going to be much more common,” Martin said. “It’ll start to look surprising if we don’t see projects like this at the largest loads as they connect [to the grid].”

A clarification was made on Oct. 25, 2025: This story originally stated that the local utility studied how many times per year the local grid could run out of electricity if the data center got built. The piece has been updated to clarify that the utility studied how big the battery would need to be to compensate for challenges imposed on the local grid by the data center.

Energy affordability has become a flash point over the past few months. It’s a key issue in this year’s gubernatorial races. It’s something President Donald Trump has promised to fix by boosting fossil-fuel production. And of course, it’s showing up in the bills that arrive in mailboxes every month.

Three-quarters of Americans count electricity costs as a source of stress in their lives, according to a new Associated Press-NORC survey. But a recent study from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory provides more nuance to the conversation. When adjusted for inflation, 31 continental states actually saw their power prices decline from 2019 to 2024, while the other 17 states experienced increases.

One reason why some states saw prices jump? Utility spending on disaster recovery and preparedness. Take California, where utilities have added billions of dollars in wildfire-recovery costs and mitigation programs to retail electricity prices in recent years, the national lab found. It’s a bracing fact as the planet warms and disasters become more frequent and destructive.

But the report also tempered fears that the growth of data centers and other power-hungry industries will jack up electricity prices. Grid maintenance has been a top driver of increased electricity costs over the last few years, but spreading these expenses among more customers — like data centers and manufacturers — has helped lower retail electricity prices, researchers found. One caveat: That dynamic tends to benefit large, commercial consumers more than residential ones.

The Trump administration has elevated fossil fuels as a solution to rising electricity bills, positing that more coal and gas power can cut prices. But building a new gas-fired plant is increasingly expensive and takes years, and the U.S. is preparing to ship more liquefied natural gas out of the country anyway.

If you look at two rare examples of power utilities reducing their rates, it’s clear that falling back on coal isn’t the answer either. In Oregon, Idaho Power Co. has asked regulators to lower electricity prices by nearly 1%, saying the closure of a coal-fired power unit and demolition of another coal plant have brought down costs. And in Virginia, where a state law is pushing the electricity sector to lower emissions, Appalachian Power cited the addition of renewable power in its request to lower rates. West Virginia is meanwhile pushing to keep its coal plants running — a move that Appalachian Power said would raise prices for its electricity customers in that state.

But putting the national lab’s inflation-adjusted numbers aside, it’s clear that rising utility bills are reaching a fever pitch across the country — and it’s going to take both more clean energy and smarter utility regulation to rein them in.

Trump sinks a global shipping-decarbonization plan

Until a few weeks ago, the International Maritime Organization was on track to approve a global shipping-decarbonization strategy. That is, until the Trump administration launched a last-minute offensive and got the United Nations body to delay adoption of the plan, Maria Gallucci and Dan McCarthy reported late last week.

The tens of thousands of shipping vessels that travel the oceans are responsible for about 3% of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions. But as Maria points out in her follow-up dive into shipping decarbonization, the industry doesn’t currently have much incentive to replace dirty diesel-powered vessels with lower-carbon alternatives.

Some good news, some bad news for U.S. battery startups

The U.S. Department of Energy slashed another wave of federal funding this week, targeting $700 million in grants for battery and other clean manufacturing projects. Nearly half of that funding had been awarded to Ascend Elements, which had already canceled a portion of its planned battery-recycling facility in Kentucky earlier this year. A smaller portion was going to American Battery Technology Co., which said it will carry on with its lithium mine and refinery project in Nevada.

But it wasn’t a bad week for every battery company. Redwood Materials raised $350 million, which it’ll use to expand its unique energy-storage business that packages together used EV batteries into grid-scale resources that can power data centers and other industrial users. And Pila Energy raised $4 million to keep building batteries that provide backup power to large appliances, but are more affordable and portable than whole-home systems like the Tesla Powerwall.

Losing the reactor race: China has a clear head start on the U.S. when it comes to nuclear power, as China has figured out how to produce reactors cheaply and quickly, while the U.S.’s last project went billions of dollars over budget. (New York Times)

What whales? The Trump administration has repeatedly blamed offshore wind farms for whale deaths but just canceled funding for research meant to protect the marine mammals in an increasingly busy ocean. (Canary Media)

Drill here, drill there, drill everywhere: The Trump administration opens 1.56 million acres of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge’s coastal plain to new oil and gas leasing, and reportedly plans to open significant swaths of the East and West coasts to offshore drilling as well. (New York Times, Politico)

Testing the grid: Xcel Energy is taking different approaches to building out distributed energy resources depending on the state, installing batteries at local businesses in Minnesota while pursuing a more complicated, legislatively mandated model in Colorado. (Latitude Media)

Battling battery blazes: California passes a new law to strengthen fire-safety standards for grid battery systems after a devastating blaze in Moss Landing earlier this year, though new storage-facility designs have already made similar fires unlikely. (Canary Media)

Flagged and forgotten: The United Nations says governments and oil and gas companies are ignoring nearly 90% of leaks that methane-tracking satellites have detected for them. (Reuters)

A winding road to decarbonization: Rondo Energy’s “heat batteries” could be key to decarbonizing heavy industry, but the company’s first industrial-scale test is at a controversial site: a California oil field. (Canary Media)

From AI to Facebook to Google Maps, the nation’s demand for computing power is growing, with households in the U.S. now averaging a whopping 21 devices — think smartphones, TVs, and thermostats — all connected to the internet.

That was one of many statistics lobbed at North Carolina utility regulators last week as they gathered to grapple with the coming onslaught of data centers, the immense buildings filled with hardware that make our around-the-clock connectivity possible but could strain the state’s electric grid, raise utility bills, and increase pollution.

Over the course of a two-day discussion on how to avoid these downsides, one simple solution came up again and again: Data centers could commit to limiting their electricity consumption slightly for a handful of periods during the year, formalizing the practice of modulating energy use that’s already standard across the industry.

“One of the issues that the commission is particularly interested in is load flexibility,” Karen Kemerait, the commissioner presiding over the technical conference, said to more than one presenter last week, before pressing them on the concept.

In response to Kemerait, experts from Google and other tech giants, along with North Carolina’s predominant utility, Duke Energy, all voiced degrees of support for the notion.

Yet how and whether regulators move to actualize load flexibility remains unclear. The Utilities Commission isn’t required to take action following its Oct. 14 and 15 meeting. And unlike other reforms repeatedly mentioned, such as a special tariff for data centers, the policy doesn’t easily translate to a rate case or other dockets before the panel.

That’s part of why Tyler Norris, a former solar developer and a thought leader on load flexibility who presented last week, hopes it will become a choice for data centers if nothing else.

“At minimum, why not have a voluntary service option that enables a large load to connect faster in exchange for bounded flexibility?” Norris told Canary Media. “In every conversation I’ve been in, I’ve heard no objection to the idea. Obviously, it’s at the discretion of the commission — whether they want to encourage it.”

Data centers aren’t the only new large customers driving ever-growing electricity demand forecasts in North Carolina, which Duke used to justify a massive new fleet of gas plants in its most recent proposed long-term plan. But the centers are the most voracious consumers by far, accounting for over 85% of the energy demand in the economic development pipeline, the utility said last week.

Not all of these facilities in the pipeline will come to fruition: It’s not uncommon for tech companies to request grid connections in multiple locations before deciding where they’ll actually build. But many will materialize, posing thorny issues for the utility and its regulators.

What if Duke can’t build generation quickly enough to serve the energy-hungry centers? Can the company do so while still zeroing out its carbon pollution, as required by state law? How can regulators assure that tech giants, not residential customers, pay for new power plants and associated upgrades to the grid?

Load flexibility could provide an elegant answer to these vexing questions.

The idea is rooted in a counterintuitive reality: Data centers don’t run at maximum tilt 100% of the time — they routinely adjust processing power even as we can post videos to Instagram or EMS responders can transmit lifesaving patient data in the middle of the night.

That’s true for a number of reasons, Norris wrote on his Power and Policy site, including the fact that computer chips could overheat if stretched to their maximum theoretical processing speeds 24/7 and also that data centers plan for redundancy.

“Many facilities are overbuilt to ensure uptime, with servers periodically taken offline for routine maintenance, software upgrades, or hardware replacements,” Norris explained in the August post.

Information on data centers’ exact electricity use is scant, and it appears to vary based on type, but research suggests the facilities’ peak consumption is about 80% of what they could pull from the grid.

Yet utility planners typically assume otherwise, categorizing data centers as “firm loads” that need “firm capacity,” such as an on-demand power plant with an ample supply of fuel, plus an extra reserve margin — in Duke’s case, 22% — in the event of emergency.

In the simplest terms, while Duke might build 122 megawatts of generation to serve a data center that can draw a maximum of 100 megawatts of electricity, the center may never use more than 80 megawatts.

But if prospective data centers were transparent about their electricity-utilization plans and committed to them on paper, utilities could adjust how they anticipate new power capacity — averting the construction of massive amounts of fossil-fuel infrastructure as well as expensive grid improvements.

In September, analytics groups GridLab and Telos Energy published a report finding that Nevada’s biggest utility could delay the need for hundreds of megawatts of new power plants if data centers committed to modest flexibility terms that allow “uptimes” of 99.5%.

Similarly, Norris, a Ph.D. student at Duke University — which has no connection to the utility — is the lead author of a February paper showing that if data centers shaved just 0.5% off their use over the course of the year, 4.1 gigawatts of power capacity in Duke’s territory in the Carolinas could be avoided.

The figure “isn’t everything in terms of their load forecast,” Norris told regulators last week, “but it is arguably a meaningful share.”

While enlisting data centers to curtail their own energy use is still more theory than practice, that’s slowly starting to change. Pacific Gas and Electric in California, for instance, has piloted flexible service agreements that could get data centers online more quickly.

In August, Google announced voluntary flexibility agreements with Indiana Michigan Power and the Tennessee Valley Authority. The following month, the tech giant revealed a similar arrangement with Entergy in Arkansas.

The company vaunted those agreements, along with its plans to self-generate carbon-free electricity, at last week’s meeting. “Google is leaning in,” Rachel Wilson, a representative for the company, told commissioners.

The Data Center Coalition is an alliance of Google, Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, and dozens of other companies that own, operate, or lease data-center capacity. The coalition listed “voluntary demand response and load flexibility” as a recommendation to regulators last week, so long as data centers could get something in return — such as a quicker connection to the grid.

“There has to be some reciprocal value for data centers,” said Lucas Fykes, director of energy policy for the coalition.

Still, the AI race, a lack of transparency about data-center electricity use, and a genuine inability of anyone in this space to predict the future could complicate efforts around load flexibility.

“Not even the most sophisticated data center owner-operators” know what their load will look like in “a rapidly shifting competitive landscape,” Norris wrote in August. “Amid such uncertainty, their preference is generally to maintain maximal optionality.”

Indeed, though Duke expressed openness to load flexibility last week, the company advised caution for the long term.

“Looking at these [load-flexibility agreements] as temporary is important,” said Mike Quinto, the company’s director of planning analytics. “A well-designed voluntary program, that’s great. It’s not something we think should be mandated on a long-term basis.”

And while utilities are well-practiced in demand response for large industrial customers, Public Staff, the state-sanctioned customer advocate, voiced worry last week about scaling the same concept to data centers.

“We haven’t seen these magnitudes trying to interconnect and … potentially drop off the system,” said Dustin Metz, director of the agency’s energy division. “From an academic standpoint, if we can shave off some of those peaks, then that could potentially reduce some of the generation assets that we need to build out,” he said. But enforcement would be essential, and North Carolina is still new to data-center growth. “We’re a little bit of a living lab,” he said.

Home batteries tend to come in two flavors. There are the no-frills, portable systems meant for emergencies, not for full-on integration with solar panels or the power grid. And then there are the Tesla Powerwalls of the world: smart, large devices that can power an entire home but which require a lot of time and money to install.

Cole Ashman, CEO of Pila Energy, wanted to build a battery that combines the best of both of those options — something that is affordable and useful in an emergency but also able to help customers on a daily basis. His years of work at smart-electrical-panel startup Span and as a Powerwall engineer at Tesla gave him the technical chops. His experience growing up in New Orleans and witnessing the aftermath of post-Hurricane Katrina power outages gave him the motivation.

“There’s this need for energy resilience — and hurdles for adoption that exist today,” he said. “We want to bring forward this notion that you don’t have to compromise on the not-so-smart battery or overspend on the primo solution. This is a middle ground.”

The result, the Pila Mesh Home Battery, debuted at the South by Southwest 2025 conference in Texas this spring. On Tuesday, Pila announced it has raised $4 million to scale up manufacturing, via a seed funding round led by R7 Partners and joined by Toyota Ventures, Refactor Capital, GS Futures, and others. The startup aims to deliver its first batteries to customers in early 2026.

Pila’s 1.6-kilowatt-hour batteries retail for $1,299, which is more than what you’d spend for another portable battery with roughly equivalent storage capacity. But unlike the typical portable backup battery, Pila’s sleek, briefcase-sized units are designed to be a constant companion for key home appliances. Set-up is simple: Just plug the battery into a standard wall outlet and connect the equipment you want backed up.

Take a refrigerator — one of the most important things to keep powered when the electricity goes out. Ashman recalled seeing thousands of them on New Orleans street curbs following Hurricane Katrina, abandoned after multiday power outages left them filled with spoiled food.

One Pila battery can power a typical refrigerator for 32 hours, or double that for customers that tack on an “expansion pack.” It also comes with wireless sensors that can be placed inside a fridge to monitor internal temperatures and with on-board sensors that can detect signs of incipient failure of refrigerator compressors from fluctuations in electricity use.

Pila’s batteries don’t just provide value to their owners during blackouts; the devices are also functional when the grid is up and running. They can be programmed to store energy when it’s cheap — say, during midday hours when grid prices are low or rooftop solar is abundant — and deploy that power during afternoon or evening hours, when households often pay higher rates for electricity from utilities.

These are the kinds of features that come standard with large, high-end home batteries like the Tesla Powerwall, sonnenCore+, Enphase IQ, and FranklinWH. But a typical Powerwall costs between $12,000 and $16,000 to buy and install — and the vast majority of them are in owner-occupied single-family homes that went through fairly extensive permitting and utility interconnection processes.

Pila batteries, by contrast, are what Ashman describes as “permissionless” energy infrastructure.

“You don’t ask for permission to put in a new refrigerator,” he said. “Why does this have to be any different?”

That puts Pila in a category of “do-it-yourself” energy systems that are gaining traction around the world.

Take balcony solar systems, which now power more than a million households in Germany and are starting to take off in other European countries. These portable panels generate only a fraction of what rooftop solar systems can provide, but they cost a lot less and can simply plug into an outlet — a much simpler process than getting a professionally installed rooftop array.

Yet balcony solar hasn’t caught on in the U.S., where electrical codes put strict limits on devices that send power back into household circuits. For now, Pila’s software is configured to only allow power to flow from wall sockets into its batteries, not vice versa, Ashman emphasized.

However, as more states pass laws promoting DIY solar and as electrical codes evolve to allow intelligently controlled devices to safely deliver power through wall sockets into household circuits, Pila Mesh batteries can flip to serve that task, Ashman said.

The do-it-yourself design also makes Pila batteries suitable for renters and people living in multifamily housing, who are largely locked out of the solar and battery market today, he said — a frustration Ashman himself has experienced as a renter in New York City.

Consumers want to be able to adopt batteries, solar panels, EV chargers, and the latest all-electric appliances as they see fit, said Andrew Krause, CEO of Northern Pacific Power Systems, a California-based contractor that specializes in solar and battery installations. He’s involved in the Agile Electrification coalition, a group of companies and researchers working to overcome barriers to people electrifying their homes.

“It’s important not to view these things as standalone assets, because as standalone assets they’re marginal. A Pila battery on the grid looks like a vacuum cleaner,” Krause said. “But I’m buying a Pila battery because I have solar on my roof, and I’m trying to handle certain end-use loads that will benefit from a battery and solar, and for which I don’t want to overcommit for a whole-home battery system.”

“It’s just a fractional Powerwall,” he said.

That ethos is appealing to Mackey Saturday, an investor at R7 Partners, which led this week’s investment in Pila. He splits his time between a New York City apartment and a home in Nosara, Costa Rica — and he’d like to have more flexible options for backup power in both places.

“In Costa Rica, while power is readily available, it’s consistently on and off,” he said. “If you want to keep your critical appliances available — not resetting clocks, not having food waste, not having your internet die — that’s hugely valuable.”

Meanwhile, “in New York we have pretty reliable energy,” he said. “But we also have some pretty challenging weather as of late,” like the June heat wave that forced utilities and government officials to issue emergency alerts asking people to conserve energy.

Someday, when Pila’s batteries get the OK to send electricity back to the grid, they could help relieve pressure on the power system, Ashman said.

Ashman highlighted numerous features that could allow Pila batteries to work together as virtual power plants, starting with the wireless mesh network built into each system. The network runs on a 900-megahertz band and allows the batteries to communicate through the walls of a home or even “a 200-unit New York City skyscraper,” he said.

Each battery also contains a cellular modem along with WiFi connections to ensure that individual and meshed batteries have multiple ways to stay in contact with their owners, building managers, or utility control centers, Ashman said. That kind of redundancy is a must-have for eventual use as a grid asset, he added.

Pila is in preliminary discussions with utilities on this front, although it isn’t naming any names. But Ashman noted that the startup presented alongside other providers of plug-and-play home-energy tech, like CraftStrom Solar, at a September pitchfest hosted by the California utility Pacific Gas and Electric.

U.S. utilities have a decidedly mixed track record in terms of how they treat customers installing rooftop solar and backup batteries. Across the country, utilities have campaigned to claw back net-metering incentives for consumers who send solar energy back to the grid, seeing that framework as a threat to electricity sales and a risk to the power system’s stability.

But utility regulators and policymakers are increasingly eager to use these distributed technologies to avoid expensive upgrades to the grid. As electricity demand grows and these cost pressures become more acute, the appeal of systems like Pila’s could grow even larger.

“We’re firm believers that batteries will be inside everything,” Ashman said, echoing a conviction shared by an increasing number of startups, especially in the induction-stove sector. “But we need those batteries to be smart. Having an unintelligent battery in everything might be good for backup, but it doesn’t help solve broader problems in the home or for energy.”