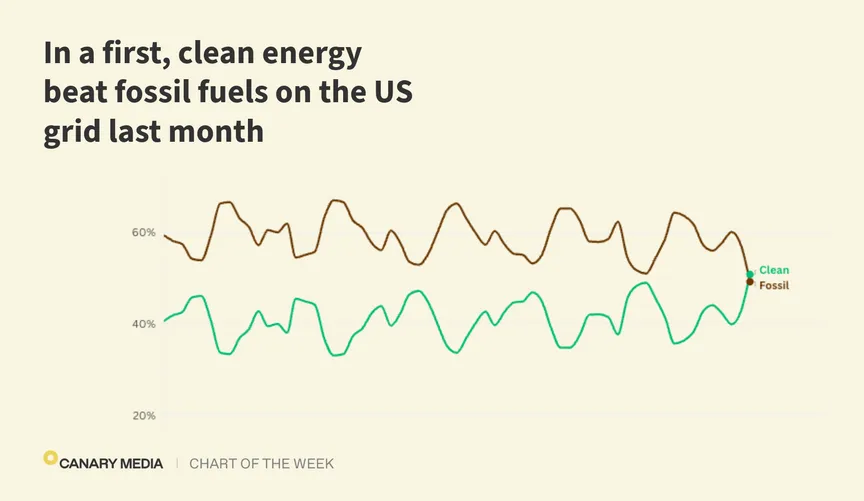

For the first time, fossil fuels accounted for less than half of U.S. electricity production across an entire month as clean power generation surged in March.

Last month, fossil gas and coal made up just over 49% of power generation, while solar, wind, hydropower, biofuels and other renewables, and nuclear met 51% of demand, new data from think tank Ember shows.

The data point is a striking example of how far the U.S. energy transition has come in recent years.

A decade ago, the U.S. got nearly two-thirds of its power from fossil fuels. But after years of building mostly solar, wind, and batteries, the country has started to close that gap. Just last month solar and wind generation jumped by 37% and 12% respectively, compared to March 2024. Meanwhile, fossil-fuel generation fell by 2.5%.

It’s worth noting that this happened at the start of the spring “shoulder season,” which runs from March to May in the U.S. and is a sort of stars-aligning time for clean energy performance.

There are a few reasons why. Milder temperatures mean people use less energy to heat and cool their homes, so power demand tends to contract. That has historically made shoulder seasons — the fall version runs from September to November — a good time to take fossil-fuel and nuclear power plants offline for maintenance. Meanwhile, wind production peaks in the spring, and solar production comes more alive with the longer days of stronger sun. Last month, solar and wind alone met over 24% of overall U.S. power demand.

But still: The shoulder seasons are always a stars-aligning time for clean energy. They were last year and the year before that and the one before that, too. Yet in the U.S., clean energy has never before beaten out fossil fuels for a whole month, no matter the season. That’s what makes this a significant moment.

It’s also notable given the current political hostility toward clean energy in the U.S. — and the federal government’s re-embrace of fossil fuels.

President Donald Trump wants to halt all wind turbine construction. Congressional Republicans are considering cutting Inflation Reduction Act tax credits that incentivize clean energy projects. Trump’s aggressive tariffs on China, which remain in place even after he paused “reciprocal” levies on every other country, could drastically slow the battery storage boom. And the president just this week signed a clutch of executive orders aimed at boosting coal, a highly polluting energy source that also happens to be in structural decline because it cannot compete with fossil gas or renewables on cost.

Even in spite of those headwinds, renewables continue to soar to new heights, underscoring the fact that clean energy is no longer a marginal part of the U.S. power system — but a cornerstone that is here to stay.

An anticipated data-center boom is driving utility plans for massive natural gas investments in southeastern Wisconsin, raising objections from customer and climate advocates.

Critics say they’ve seen big development plans fail to pan out before, and they don’t want to be stuck paying for overbuilt fossil-fuel generation based on increasingly uncertain growth projections.

Wisconsin Electric Power Co. (WEPCO) says it needs to build new gas generation to power a planned $3.3 billion Microsoft data center near Mount Pleasant. The project is on the site of the failed Foxconn LCD screen factory, a proposed megaproject that President Donald Trump promised during his first term would become “the eighth wonder of the world” but that never materialized as planned.

“There’s a lot of healthy skepticism because of the Foxconn project never reaching anywhere near the scale that was being touted,” said Tom Content, executive director of the Citizens Utility Board. “People are asking, ‘Is this real this time?’”

Microsoft has already paused construction on the data center as it reevaluates the scope and how “recent changes in technology” may affect the project. A Chinese artificial-intelligence company in January announced a major breakthrough that it claims allows it to offer AI services with far less computing power, upending global assumptions about the industry’s electricity demand.

Microsoft is also proposing a data center in nearby Kenosha, and a developer called Cloverleaf Infrastructure is proposing one in nearby Port Washington. But the specifics of these data centers and their energy demand are not confirmed, hence critics say the utility hasn’t demonstrated that demand will increase enough to justify the roughly $2 billion in natural gas investments proposed by We Energies (WEPCO’s trade name). Critics also note that an influx of natural gas power seems to contradict Microsoft’s own climate goals of being carbon-negative by 2030.

“We Energies says they want to be ready for other potential customers but has provided no proof of who those customers are or what they want in terms of their energy sourcing,” said Gloria Randall-Hewitt, a resident who spoke at a March 25 hearing held by the Wisconsin Public Service Commission. These projects “carry huge price tags in terms of pollution, detrimental health outcomes, and rate increases for customers. They are asking us to just trust them.”

We Energies is looking to build a new five-turbine, 1,100-megawatt gas plant in Oak Creek on the same site as two large coal plants, one of which is closing this year. We Energies also plans to build a 128-MW gas plant in Paris, Wisconsin, 25 miles south of Oak Creek. The utility proposes serving the plants with a new liquefied natural gas storage terminal at the Oak Creek plant site, by Lake Michigan’s shore, and with a new 33-mile pipeline.

The Oak Creek gas plant would go online in 2027 or 2028, the utility says, and cost around $1.3 billion. The Paris plant, made up of seven reciprocating internal combustion engines, could go online next year, at a cost of roughly $300 million. WEPCO needs the storage terminal, which will cost about $520 million, to make sure the plants and residential customers have enough gas, as well as to meet requirements established by the Midcontinent Independent System Operator, which manages the region’s grid, utility spokesperson Brendan Conway said by email. The new pipeline would cost about $210 million.

The three-member Public Service Commission will decide whether to grant the utility the right to recoup those costs — and a profit — from ratepayers. After overwhelming turnout at the public hearing on Oak Creek, the commission extended the public comment period for the proposed plant through April 7. That was also the deadline for comments on the storage terminal, and the commission completed a comment period for the Paris proposal earlier this winter.

In an April 1 filing before the commission, We Energies said it forecasts 1,800 MW of increased demand in the next five years, and even if only 450 MW of that demand materializes, building the gas plants is the most cost effective way to meet it. Conway said the Oak Creek gas plant would save ratepayers $413 million compared to other alternatives.

But advocates don’t believe that and hope the commission orders the utility to consider other options and do more study.

“We understand there needs to be increased energy production to meet that load, but we want to make sure it’s the most cost-competitive suite of options, not just defaulting back to natural gas as a baseline,” said Emma Heins, principal at Advanced Energy United, an industry association representing transmission, generation, and transportation-related companies.

The Citizens Utility Board, Advanced Energy United, and other experts say the situation highlights Wisconsin’s lack of an integrated resource plan. Most states require utilities to undergo these comprehensive planning processes to meet predicted energy demand, but Wisconsin utilities simply bring proposals to regulators on a case-by-case basis. Advocates say centralized planning would avoid unnecessary generation investments and facilitate more investment in renewables.

“There’s a larger governance issue” in how decisions around energy infrastructure are made, said Courtney Brady, deputy director for the Midwest region at Evergreen Action, a nonprofit policy advocacy group. “That speaks to the fact that without an integrated resource plan in Wisconsin, you’re going to be more subject to these big proposals that could end up being costly unused infrastructure. I don’t think WEPCO has done their job in understanding the alternatives that exist, partly because they are not required by law to do so.”

We Energies currently gets only 5% of its energy from renewables, with 28% from coal and 37% from natural gas. Its investment in renewables lags behind other Wisconsin utilities like Xcel Energy, which generates half its energy carbon-free, and Madison Gas and Electric, which plans to be carbon neutral by 2050 and supplies the city of Madison with 24% renewable energy.

Conway said We Energies is investing over $9 billion in new renewable energy by 2029 and will eliminate coal-fired power by 2032. He said demand-response programs and renewables would still not be enough to meet the expected new demand.

“Now more than ever — it is critical for us to have quick-start gas plants available and running when the wind doesn’t blow and the sun doesn’t shine,” he said by email.

Heins noted that WEPCO was “one of the last utilities in the country to build a large-scale coal plant.” In 2011, it spent $2.3 billion on a new coal plant at the Oak Creek site; the utility now plans to convert that plant to natural gas “in the coming years,” Conway said. Around the same time it built that coal plant, WEPCO invested close to $1 billion in pollution controls for another Oak Creek coal plant that is closing this year, leaving ratepayers with $645 million in stranded costs, as noted in an analysis by think tank RMI.

“This utility has a history of being behind the times on technologies,” Heins said. “Our sentiment is a lot of energy options are being left on the table, technologies that can be implemented much faster than a natural gas plant.”

RMI’s analysis notes that under the utility’s proposal, customers will on average pay an extra $78 a year to finance the Oak Creek gas plant, but that amount could climb to $136 a year if fuel and equipment cost increases considered possible by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory come to pass. RMI and other experts note that U.S. plans to build more LNG terminals to facilitate exports also mean that gas prices will likely rise and become more volatile, to the detriment of U.S. ratepayers.

Conway noted that WEPCO filed a March 31 request with the Public Service Commission to approve a rate structure where data centers would pay for generation infrastructure planned to meet their needs. Content said the proposal is a step in the right direction but lamented that the gas projects could be approved long before there is any certainty about the new rate plan.

Residents testifying at the Oak Creek public hearing also expressed fears about the health impacts of new gas generation, especially since they have already spent years suffering air pollution from the nearby coal plants.

The closure of those coal plants is a victory for public health and the environment — one that would be undermined by the construction of unnecessary, polluting gas plants, said Abby Novinska-Lois, executive director of Healthy Climate Wisconsin, an advocacy group led by medical professionals

“This isn’t a transition,” she said. “This is a brand new health threat to the area that isn’t necessary when we have energy efficiency and clean energy alternatives that can also meet the demand.”

Landfills are a major problem for the climate: They’re the United States’ third-largest source of methane, a greenhouse gas that traps 80 times as much heat as carbon dioxide in the short term. Last year, the federal government was poised to start reining in these emissions: In July, the Environmental Protection Agency announced that it would release new regulations to better detect and prevent methane leaks from landfills.

The Trump administration, which has announced its intention to cut the EPA’s budget by 65% or more, seems unlikely to follow through on these plans or any other policy limiting landfill emissions.

But in the absence of federal leadership, states like Michigan, Oregon, Colorado, and California are moving forward with their own plans. Regulatory efforts are underway among these climate leaders to implement stricter rules for landfill operators and require the use of novel technology, like drones and satellites that monitor leaks.

“These state regulations could be hugely impactful,” said Elizabeth Schroeder, the senior communications strategist at Industrious Labs, a nonprofit working to transform heavy industry. They not only have the potential to make a real dent on greenhouse gas emissions, Schroeder said, but could also set a national example for other states looking to curtail methane pollution.

Currently, the EPA requires landfill operators to cover trash to minimize odor, disease risk, and fire — a practice that also minimizes methane leaks. This usually looks like a layer of dirt or ash, followed by tarps. Operators of large landfills must also install extraction systems, networks of pipes that collect methane and other gases from inside the landfill. The extraction systems then pump these emissions to burn off at flares or, increasingly, to biogas energy projects. However, landfills are dynamic systems — over time, as waste breaks down and shifts, cover develops holes and pipes crack.

Maintenance is often imperfect. An analysis by the Environmental Defense Fund found that between 2021 and 2023, more than one-third of landfills had at least one violation of EPA standards. Operators of landfills that exceed a specific emissions threshold are supposed to conduct quarterly “walking” surveys for leaks. But experts say that these surveys are infrequent and often miss large portions of the landfill.

States have an opportunity to step up those standards — not only by lowering emissions limits but by improving the maintenance and monitoring of landfills, said Tom Frankiewicz, the waste-sector methane expert at climate-focused think tank RMI. “While we would love to see all this done comprehensively in one national-level regulation, it’s states that are taking the lead on deployment of advanced technology and setting new best practices for landfills.”

In 2010, California became the first state to develop standards for landfills that were stricter than federal rules. Those included a lower emissions threshold at which landfills had to install gas collection systems and a requirement that operators enclose flares so that the methane burns more efficiently. Other states, including Oregon and Washington, followed suit and in some respects even surpassed California, said Katherine Blauvelt, the circular-economy director for Industrious Labs. But despite this early progress, landfills in these states and elsewhere continue to spew methane and undermine climate goals.

Now, though, Colorado has taken the lead on a new generation of landfill emissions regulations. The state is developing what some experts are calling a first-of-a-kind program for monitoring and responding to methane leaks from landfills. As part of the initiative, Colorado plans to implement remote-sensing technologies, including fly-overs and satellites, to detect methane leaks, which operators would then be required to address.

“Colorado would be the first state to incorporate that into a rule where, instead of relying on voluntary follow-up, there would actually be requirements around mitigating emissions that are detected,” said Ellie Garland, a senior associate focusing on methane policy at RMI. A draft rule will be publicly available in April, with a final vote expected in August.

In addition, Colorado’s Department of Public Health and Environment is considering additional requirements for landfills that include stricter rules for the maintenance of cover and a lower threshold at which landfills are required to report and control emissions, Garland said. Currently only 15 of the state’s about 50 active landfills do this, although Colorado began requiring 35 more landfills to begin reporting emissions starting on March 31, said Clay Clarke, the manager of the climate change program at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Not all landfills are required to control emissions. That’s because smaller landfills don’t generate enough gas to collect and flare. Under proposed regulations, many of these landfills would need to pipe gas to biofilters — a system that uses microorganisms to digest methane.

Meanwhile, the California Air Resources Board is working to update its landfill emissions regulations. Under CARB’s anticipated timeline, these will take effect in 2027. Last December, the agency held a workshop to discuss potential new rules. Those included a lower safe limit for methane emissions, limits on how long operators can turn off their gas collection systems for landfill maintenance, and stricter rules for collecting gas at closed landfills. Under current regulations, landfill operators must collect gas for only 15 years after a landfill closes even though the area can continue to leak methane for 30 years or more. The agency is also considering regulations that would require some operators to install automated well-tuning technology that monitors and adjusts the gas-extraction system in real time.

One of the most promising new regulations CARB is considering is a “super-emitter” program for landfills, Blauvelt said. The EPA defines a super-emitter event as a plume of methane leaking at a rate of more than 100 kilograms per hour. In 2019, NASA scientists estimated that these highly concentrated leaks account for one-third of California’s methane emissions.

Between 2020 and 2023, CARB partnered with the University of Arizona and the nonprofit Carbon Mapper to track down super-emitter events by flying over landfills in planes equipped with sensors that can detect methane plumes. If Carbon Mapper identified a leak, it notified CARB, which would get in touch with the landfill owner. However, operators weren’t required to take action. Later analyses found that operators fixed about half of the reported leaks.

Updated rules could require landfill operators to swiftly respond to methane plumes. The program would be similar to the super-emitter program already in place for California’s oil and gas industry. That program requires operators to follow up with on-the-ground monitoring within five days of learning about a leak, come up with a repair plan 72 hours later, and fix the leak within two to 14 calendar days, depending on its severity.

The state is also looking into other remote-sensing technologies, like drones and on-the-ground infrared monitors, which would provide a more continuous and finer-resolution picture of methane emissions.

California emits the second largest share of greenhouse gases in the U.S. A recent Industrious Labs analysis found that if the state were to adopt these stricter regulations, it could reduce its landfill emissions 22% by 2030 and 64% by the end of the century.

Other states are renewing their efforts, too. In Oregon, newly proposed Senate Bill 726 would require landfill operators to deploy commercially available drones and advanced monitoring technologies (including satellite and airflight) to detect methane plumes across landfills.

Meanwhile, in Michigan, a climate bill passed in 2023 contains elements that could lead to landfills adopting better monitoring and detection. Senate Bill 271, which aims to accelerate the state’s transition to clean energy, identifies landfill biogas as a potential low-carbon fuel. “While the inclusion of recovered landfill gas as a clean energy source has come under scrutiny, there is a major silver lining,” Blauvelt wrote in an email. “Vital” language in the bill mandates that landfill operators collecting biogas use “best practices for methane gas collection and control,” as determined by Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy.

The department has yet to lay out what those “best practices” are, but better landfill cover, automated well-tuning technology, and advanced monitoring technology are all on the table, Blauvelt said.

“Given that Michigan is among the top ten states for methane emission from landfills, the potential to dramatically reduce methane and other harmful co-pollutants is enormous,” Blauvelt wrote in an email.

A 2024 analysis by Industrious Labs projected that if every state were to adopt these best practices, it could lead to a 56% drop in landfill methane emissions by 2050. Experts hope that as these climate leaders adopt stricter rules, more states will step up. In 2010, California showed that this ripple effect is possible, Blauvelt said. “The great news about this is, the solutions are known. The technology is sitting on the shelf.”

Under the Biden administration, the federal government gave out billions of dollars to companies looking to slash the planet-heating emissions from concrete, cement, and asphalt.

Since President Donald Trump took office in January, the future of that support for low-carbon materials has been thrown into question. The Environmental Protection Agency has already canceled millions of dollars in grants for the industries, and the administration is considering deep cuts to the Energy Department office in charge of a $6.3 billion industrial decarbonization program that includes major cement and concrete projects.

But bipartisan legislation the House of Representatives passed in a 350-73 vote last week would give the Department of Energy a clear mandate to develop a full program to research, develop, and deploy clean versions of the building materials.

Dubbed the IMPACT Act — short for the Innovative Mitigation Partnerships for Asphalt and Concrete Technologies Act — the bill marks just the first step of a push in Congress to bolster the nascent industry.

A second, separate bill introduced in the House just weeks ago as the 2.0 version of the legislation would allow state and municipal transportation departments to pledge to buy future output of manufacturers of low-carbon concrete, cement, and asphalt.

Sister legislation in the Senate combines features from both bills. Advocates say a bill that blends the legislation together could soon pass in both chambers as part of the next federal highway budget.

Concrete and asphalt together comprise nearly 2% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. Most of concrete’s emissions stem from its key ingredient, cement, which on its own makes up as much as 8% of the world’s carbon output.

Since roughly half of all cement and concrete in the United States is sold to governments paving roads, patching sidewalks, and building bridges, giving state and local agencies the power to guarantee future purchases of green products could help startups in the space take off, said Erin Glabets, a spokesperson for the Massachusetts-based low-carbon cement maker Sublime Systems.

“Having the weight of the federal government and ultimately having that flow through the states to support the use of clean, innovative cements in our public infrastructure is really the best thing a company working in this field can ask for,” she said.

“We’re hopeful and enthusiastic,” she added. “That’s a really powerful buying signal.”

Unlike traditional manufacturers who use a carbon-intensive process to break down limestone in fossil-fueled kilns fired up to 1,400 degrees Celsius, the company makes a replacement for Portland cement — the most common variety — using electricity and alternative materials that don’t generate carbon as a byproduct.

Sublime is currently building its first commercial-scale plant in Holyoke, Massachusetts, with money it was awarded last year through the Energy Department’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) — the office established in 2021 under the bipartisan infrastructure law whose more than $20 billion budget is staring down Trump’s chopping block.

It’s not the only such project relying on support from the under-fire office. The federal government put up $500 million last year to equip Germany-based Heidelberg Materials’ new cement plant in Mitchell, Indiana, with hardware to capture and store carbon emissions.

The facility is a rare example of a carbon capture project backed by the Sierra Club, which typically opposes technology to filter CO2 emissions out of power plant smokestacks as a bid to prolong the use of fossil fuels.

Oakland, California-based startup Brimstone won a $189 million grant last March from the same office to build a first-of-a-kind commercial-scale plant to demonstrate its technology that converts calcium-bearing silicate rocks into Portland cement with significantly lower emissions.

In total, OCED pledged to support $1.5 billion worth of low-carbon cement and concrete projects through the Industrial Demonstrations Program.

Passage of the IMPACT Act comes as several states move forward with Buy Clean policies that aim to boost low-carbon building materials.

In 2017, California became the first state to pass such a law, and the California Air Resources Board in March released a draft decarbonization strategy for the cement sector.

Eight other states, including Colorado and Minnesota, have since followed suit on Buy Clean policies. But states have limited purchasing power compared to the federal government, and in any case procurement power itself is not enough for the industry to take off — research and development funding is needed, too.

That’s what makes the federal bills so significant, said Harry Manin, the Sierra Club’s deputy legislative director for industrial policy and trade.

“When it comes to the supply side, actual money to demonstrate these technologies has been more the bailiwick of the federal government,” he said.

While Democratic sponsors such as U.S. Rep. Valerie Foushee of North Carolina may see the bills as climate legislation, Manin said the GOP recognizes “it’s important to protect these industries domestically.”

“They understand tariffs aren’t enough,” Manin said.

To that end, he said, Sen. Bill Cassidy from Louisiana is working to convince fellow Republicans to back separate legislation that would establish a carbon border adjustment mechanism, sometimes called a carbon tariff, to slap levies on imports produced in heavily emitting countries such as China and India.

But the real selling point, Manin said, is that cleaner building materials will ultimately mean cheaper building materials.

“Yes, these materials come with a premium in the short term, but since we’ll eventually commercialize materials that take far less energy to make, ultimately we’re going to be lowering costs,” he said. “That’s why Republicans are so interested.”

Airplanes. Power plants. Cars and trucks. Their images might be the first to spring to mind when thinking about the challenge posed by the energy transition.

But what about plain old buildings?

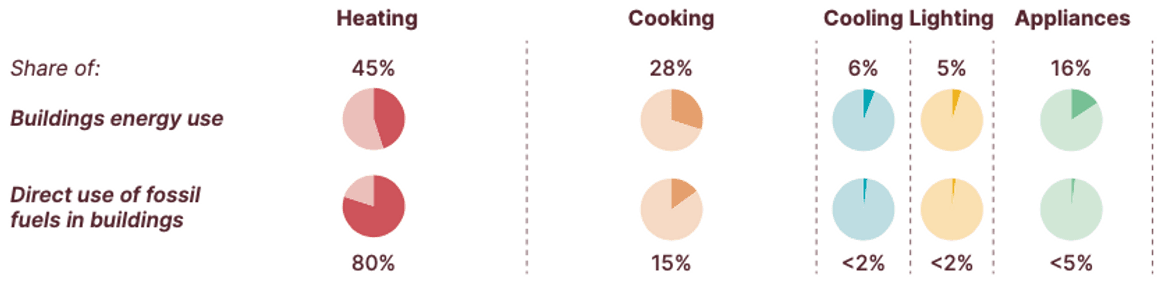

From their structural bones to the energy they constantly consume, buildings account for a staggering one-third of global carbon pollution: 12.3 gigatons of CO2 in 2022.

Most of these emissions come from their operations — the fuel burned on-site for heating and cooking and off-site to produce their electricity. But 2.6 gigatons of CO2 annually, or 7% of global emissions, stems from the carbon baked into the physical structures themselves, including the methods and materials to build them, otherwise known as embodied carbon.

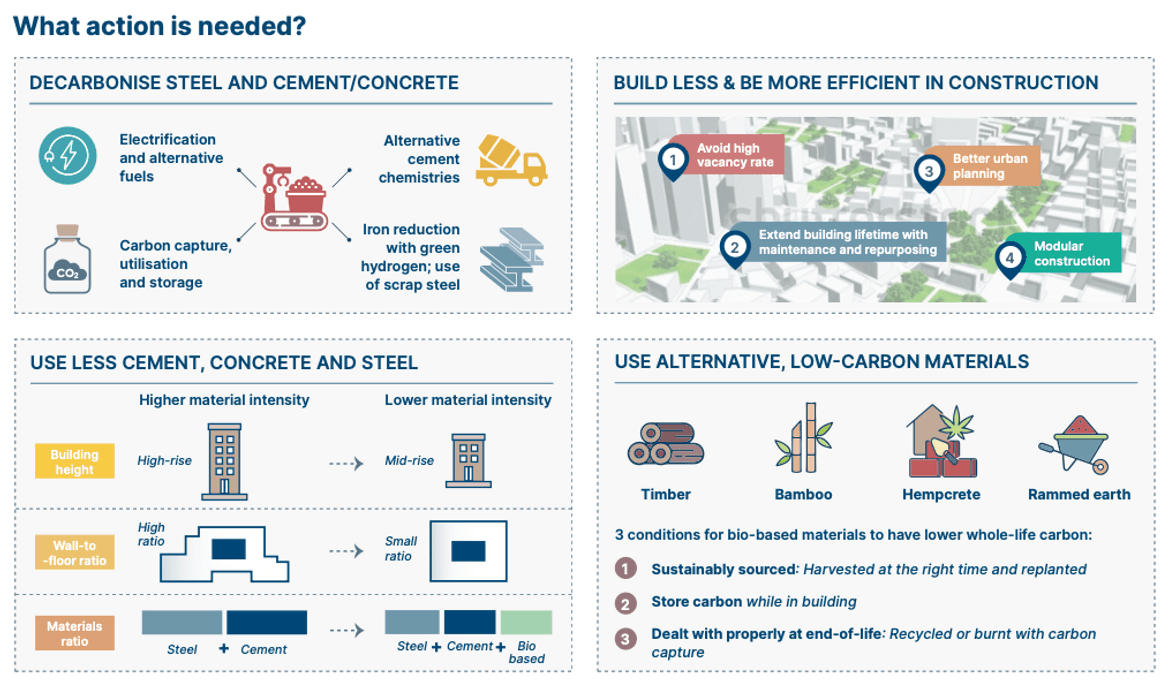

A February report lays out a blueprint for tackling each of these sources of CO2 and cleaning up buildings globally by 2050. The challenge is massive: It depends on the actions of millions of building owners. But the policy and technology tools already exist to meet it, according to report publisher Energy Transitions Commission, an international think tank encompassing dozens of companies and nonprofits, including energy producers, energy-intensive industries, technology providers, finance firms, and environmental organizations.

The report identifies several key levers that must all be pulled in order to deal with the climate problems from buildings: energy efficiency, electrification, flexible power use, and design that minimizes materials and uses cleaner ones. Each is showing varying degrees of progress around the world.

“We already have so many of the solutions that we need,” said Adair Turner, chair of the Energy Transitions Commission, at a panel discussion last month. But to implement them, “we need to change minds and practices.”

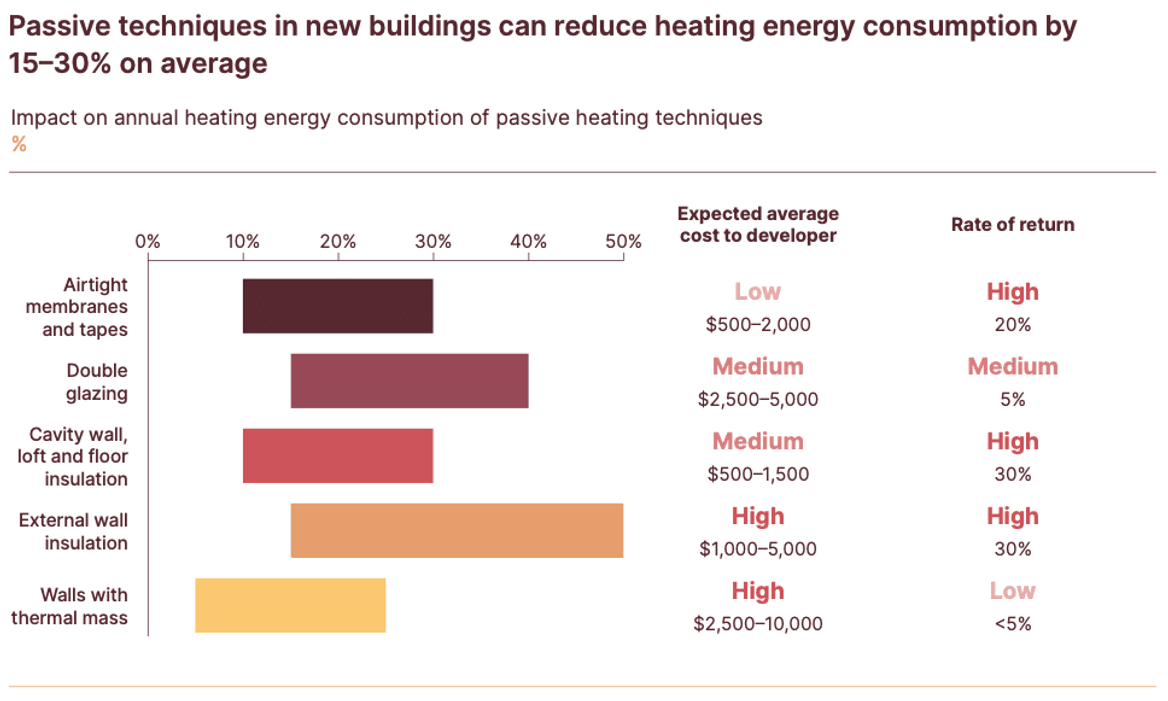

Building developers and owners can pursue a variety of strategies to make their buildings less energy-intensive and cheaper to operate without sacrificing the comfort of their residents, according to the report.

They can seal air leaks; insulate attics, walls, and floors; and install double- or triple-pane windows to make buildings snug like beer cozies. Weatherization strategies that take a medium level of effort would cut 10% to 30% of energy use, according to the report; deeper changes could slash up to 60%.

For retrofits, online tools and in-person energy audits can help owners decide which changes make the biggest difference for the climate, their comfort, and their energy bills.

Other simple techniques can combat growing demand for cooling, which globally is set to more than double by 2050 due to rising temperatures and incomes, the report notes. Passive approaches that deflect the sun’s rays, from painting roofs white to planting shade-giving trees, can slash cooling needs by 25% to 40% on average.

Efficiency measures “deliver a clear return to households over time,” said Hannah Audino, building decarbonization lead at the commission.

But because the payoffs can be slow to materialize, governments should provide targeted financing to lower-income households that might not otherwise be able to afford these upgrades, she added.

There’s also the challenge of convincing landlords to invest in efficiency measures even though tenants often pay for utility bills themselves. To ensure broad uptake, the authors recommend policymakers implement building performance standards, an approach adopted by U.S. cities like New York and St. Louis to penalize building owners who fail to meet certain emissions or energy-use benchmarks.

For new builds, energy codes and other regulated standards can set a performance floor. They differ widely worldwide, but the Passive House approach is “the gold standard,” per the report. Buildings that meet its benchmarks typically slash energy use by a whopping 50% to 70% compared to conventional constructions.

What’s more, new buildings that use 20% less energy than those built merely to code usually have a “very manageable” premium of 1% to 5%, the authors write, which can be recouped in a higher sale price for developers or lower bills for owners.

Connecting buildings via underground thermal energy networks in which they share heat can also unlock big efficiency gains — and do it faster and at bigger scales than individual action might. The report notes that they “should be deployed where possible.”

Buildings will need to be fully electrified to become climate friendly. That means swapping fossil-fuel–fired equipment for über-efficient heat pumps (including the geothermal kind), heat-pump water heaters, heat-pump clothes dryers, and induction stoves.

Heat pumps are essential to decarbonize heating, which is the biggest source of operational emissions and currently only 15% electrified worldwide, according to the report. The appliances are routinely two to three times as efficient as gas equipment, and they lower emissions even when powered by grids not yet 100% clean.

Heat pumps can come at a premium, though the authors expect prices to fall as sales grow and installers gain experience. In countries with mature markets, heat pumps can even be cheaper than gas heating systems, according to the report: Take Denmark, Japan, Poland, and Sweden.

For most homes in the U.S. and many in Europe, per the report, heat pumps are cheaper to run than gas equipment and have lower total lifetime costs. Heat pumps make even more economic sense when consumers are considering installing an AC and a gas furnace; heat pumps are both in one.

These appliances also keep getting better. Manufacturers learn how to improve technologies with experience, as they have done with solar panels and wind turbines. The result is that heat pumps are becoming more efficient; getting smaller; and reaching higher temperatures as they transition to natural refrigerants (which also have lower global warming potentials), the authors write.

But policymakers need to address energy costs to encourage widespread electrification, according to the report. Countries with high electricity prices relative to those of gas lag in heat pump adoption.

Fixes include shifting environmental levies that are currently disproportionately piled onto electricity bills to gas costs, offering lower electricity rates for customers with electric heating, and putting a price on carbon, the report says. Banning gas equipment would be the most direct move, but “only a handful of countries, such as the Netherlands, have successfully outlined plans” to do so.

Buildings will need more power when they’re all-electric, potentially straining grids. Unchecked, global electricity demand for buildings by 2050 could grow 2.5 times what it is today, per the report. But with efficiency improvements, the commission expects electricity requirements to grow a more modest 45%.

That’s still massive. So, to decarbonize buildings without breaking the grid, we’ll need to make them flexible in their electricity demand, the authors note. By using power when it’s cheap, clean, and abundant, these edifices will also be more affordable than they’d be otherwise.

Low-cost smart thermostats and sensors can reduce demand by 15% to 30% and shift energy use automatically when prices drop. In some places, commercial building owners can already reap tens of thousands of dollars in annual savings by dialing down energy use when grid demand is highest.

The report recommends that all buildings aim to have the ability to shift when they actively heat or cool by two to four hours without compromising comfort. That’s doable with existing solutions that provide thermal inertia, including insulation and tank water heaters that can store hot water for when it’s needed.

Utilities and regulators can spur more flexible demand by implementing electricity rates or utility tariffs that reward customers for using power outside of peak periods.

“When the wind is blowing and the sun is shining, and we’ve arguably got an abundance of clean power on the grid, prices often go negative,” Audino said. Tariffs can reflect that reality, creating a clear financial incentive for households and others to shift their power usage. Without these more dynamic tariffs, “it’s really hard to see how we can drive this [shift] at scale.”

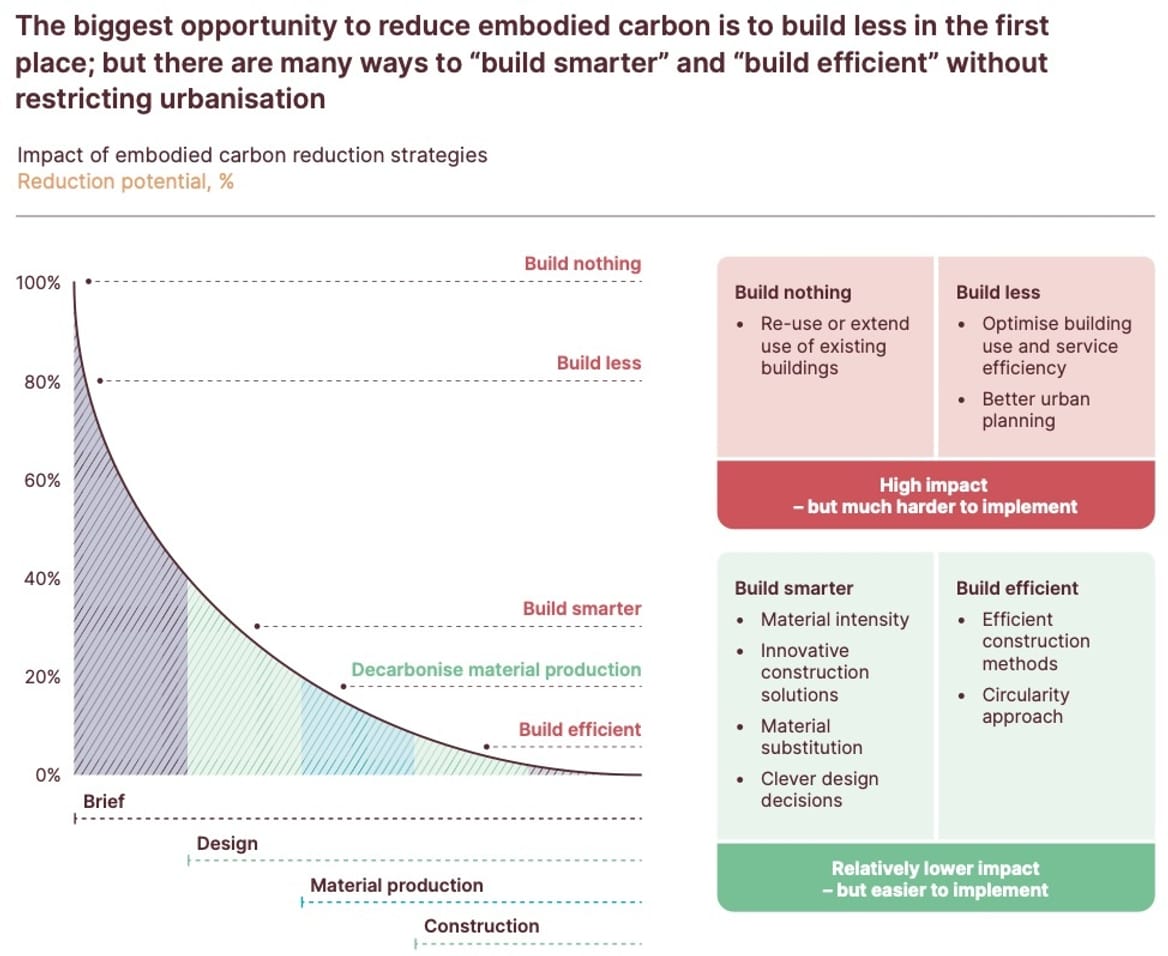

Building floor area globally is expected to grow by over 50% by 2050, according to the report. If structures are built with the same techniques as today, cumulative embodied carbon emissions could soar an additional 75 gigatons of CO2 between now and midcentury.

But that amount could be reduced to about 30 gigatons of CO2 by maximizing the utility of buildings that already exist, decarbonizing building materials, and designing new ones differently.

Using existing structures is “the biggest opportunity” for reducing embodied carbon, per the report: The strategy avoids adding any new embodied emissions at all. But it’s harder to implement this tactic than it is to change building techniques, the authors add.

Producing materials drives up-front emissions, and the biggest contributors are cement, concrete, and steel, the report notes: They account for 95% of the embodied carbon from materials in buildings.

Low- and zero-carbon cement, concrete, and steel can be made using electricity, alternative fuels, exotic chemistries (including ones inspired by corals), and carbon capture with storage. But developers need incentives to buy these clean materials, which aren’t yet widely available or competitive on cost alone.

A complementary approach is to design buildings with less of the emitting stuff. For the same floor space, a mid-rise structure uses less material than a high-rise, which needs a larger foundation and bigger columns. A boxy building is more efficient than an irregular one.

Developers can moreover supplement construction with alternative, lower-carbon materials, per the report. These include recycled materials, sustainably sourced timber, bamboo, rammed earth, and “hempcrete” — a low-strength, lightweight mixture of hemp, lime, and water that actually absorbs carbon.

Embodied carbon has been particularly challenging to curb because it’s largely invisible. In 2021, London regulators decided to change that, requiring major developers to tally all the carbon emissions, operational and embodied, over the building’s lifetime while still in the planning stage, the authors write.

Developers weren’t required to stay below any carbon-intensity threshold; they just had to report expected emissions, said Stephen Hill, associate director in the buildings sustainability team at firm Arup, a member of the Energy Transitions Commission.

“But it triggered a kind of race downwards in terms of embodied-carbon intensity for developers, all of whom wanted to have the lowest-carbon developments,” he added. “It’s a fascinating example of what transparency will do and how the market behaves.”

Stephen Richardson, senior impact director at the nonprofit World Green Building Council, emphasized at the commission’s panel event that to decarbonize buildings, governments need to do two things at once. “We need to incentivize, on the one hand, make it financially more appealing,” he said. And “we need to mandate.”

Large parts of Asia, most of Africa and South America, and even some U.S. states lack mandatory building codes, the report notes. And that’s the “absolute, No. 1” policy that needs to be in place, Richardson said. “Without policy, nothing happens — or very little.”

Evanston, Illinois, just passed an ordinance requiring the city’s largest buildings to eliminate all fossil fuels and use 100% renewable electricity by 2050.

On March 10, the Chicago suburb joined 14 other state and local governments across the U.S. that have enacted policies to decarbonize existing buildings, which often account for the bulk of a city’s carbon emissions. Evanston’s Healthy Buildings Ordinance marks the first such law — known as a building performance standard — to pass in the U.S. this year and the second to be adopted in the Midwest after St. Louis.

More could be on the way soon. Evanston is part of a wave of small cities that have recently passed building performance standards, including Newton, Massachusetts, in December. Another city outside Boston and two in California are also working on adopting standards this year, according to the Institute for Market Transformation, a nonprofit that helps state and local governments implement building efficiency policies.

Under the Trump administration, local leadership is “the only front on which the climate action battle will be fought,” said Jonathan Nieuwsma, an Evanston city council member and key sponsor of the law.

For cities that want to continue climate progress, regulating large, existing buildings is one of the best avenues available, said Cara Pratt, Evanston’s sustainability and resilience manager. Besides targeting local emissions sources, performance standards spur more proactive maintenance to ensure cities are “providing the healthiest indoor air environment possible for the folks who live and work in these buildings.”

The city of Evanston, home to around 75,000 residents, committed to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 under a 2018 climate action plan. Buildings are key to reaching that target: The city’s 500 largest structures alone account for roughly half of total emissions, and the sector overall accounts for about 80%. While the city has adopted building codes to rein in emissions from new construction, existing buildings aren’t subject to equivalent rules to make sure routine upgrades of systems like heating and cooling happen in line with Evanston’s climate goals.

The new law fills in that gap by requiring the city’s biggest commercial, multifamily, and government buildings to reduce their energy-use intensity, achieve zero on-site fossil fuel combustion, and procure 100% renewable electricity by 2050. But the ordinance itself does little aside from setting up long-term goals. Instead, it creates two groups charged with developing the detailed rules needed to actually implement the law.

One is a technical committee that will develop interim targets covering five-year intervals between 2030 and 2050, along with other regulations like compliance pathways and penalties. The other will serve as a community accountability board to ensure the policy’s design and implementation incorporates equity concerns, including by minimizing costs to low-income residents and tenants and providing support to less-resourced buildings such as schools or affordable housing.

Like other building performance standards across the country, Evanston’s policy will set limits on emissions or energy efficiency without mandating how property owners should reach those targets. Buildings can typically choose from a menu of compliance options, from weatherization and efficiency upgrades to installing heat pumps and other electric alternatives.

Nieuwsma describes Evanston’s law as “an enabling ordinance” that “sets up a process for those very important details to be developed with robust stakeholder input.” Once both committees agree on regulations, they will need to be approved by the City Council. Nieuwsma and other officials expect the city to adopt rules sometime next year.

Evanston’s policy is unusual in baking in a high level of formal input from property owners. Three out of six seats on the technical committee will be nominated directly by local building owners associations, an amendment made after several City Council deliberations. (The rest of the members of both committees will be nominated by the mayor.)

The setup is designed to address property owners’ cost concerns and could help Evanston avoid industry pushback that has stymied similar laws in places like Colorado, which currently faces a lawsuit brought by apartment and hotel trade associations against its policy.

Building performance standards are still relatively novel. The first one in the U.S. was introduced in Washington, D.C., in 2018, followed by New York City’s Local Law 97 in 2019. Four states — Colorado, Maryland, Oregon, and Washington — and 11 local governments, including Evanston, have now adopted the policy. More than 30 other jurisdictions have committed to introducing the standards as part of a national coalition that was led by the White House under the Biden administration and is now spearheaded by the Institute for Market Transformation.

Last year, the Biden administration doled out hundreds of millions of federal dollars under the Inflation Reduction Act to cities and states pursuing building performance standards. Evanston was one of them and received a $10.4 million conditional award from the Department of Energy in early January.

But since Inauguration Day, the Trump administration has attempted to freeze and claw back climate funding to nonprofits and local governments. Pratt said the federal government has not told the city that it will withdraw its grant, but Evanston has also not received word on whether the funding will be finalized.

The city had intended to use the grant to hire additional staff and support energy audits for resource-constrained buildings like public schools, Pratt said. Yet regardless of whether the city receives the money, the work to reduce emissions from large buildings will continue, she said, adding that Evanston committed to adopting a building performance standard a few years ago without the promise of federal funding. “To me, it was always a huge positive addition. But it’s not necessary to do the work.”

Jessica Miller from the Institute for Market Transformation, who served on a committee that helped the city develop its ordinance, pointed out that the country’s first building performance standards were passed during the first Trump administration. “There are many jurisdictions that have passed these types of policies without federal support,” she said.

By this time next year, a new satellite will be detecting how much methane is leaking from oil and gas wells, pumps, pipelines and storage tanks around the world — and companies, governments and nonprofit groups will be able to access all of its data via Google Maps.

That’s one way to describe the partnership announced Wednesday by the Environmental Defense Fund and Google. The two have pledged to combine forces on EDF’s MethaneSat initiative, one of the most ambitious efforts yet to discover and measure emissions of a gas with 80 times the global-warming potential of carbon dioxide over a 20-year period.

MethaneSat’s first satellite is scheduled to be launched into orbit next month, Steve Hamburg, EDF chief scientist and MethaneSat project lead, explained in a Monday media briefing. Once in orbit, it will circle the globe 15 times a day, providing the “first truly detailed global picture of methane emissions,” he said. “By the end of 2025, we should have a very clear picture on a global scale from all major oil and gas basins around the world.”

That’s vital data for governments and industry players seeking to reduce human-caused methane emissions that are responsible for roughly a quarter of global warming today. The United Nations has called for a 45 percent cut in methane emissions by 2030, which would reduce climate warming by 0.3 degrees Celsius by 2045.

EDF research has found that roughly half of the world’s human-caused methane emissions can be eliminated by 2030, and that half of that reduction could be accomplished at no net cost. Emissions from agriculture, livestock and landfills are expected to be more difficult to mitigate than those from the oil and gas industries, which either vent or flare fossil gas — which is primarily methane — as an unwanted byproduct of oil production, or lose it through leaks.

That makes targeting oil and gas industry methane emissions “the fastest way that we can slow global warming right now,” Hamburg said. While cutting carbon dioxide emissions remains a pressing challenge, “methane dominates what’s happening in the near term.”

Action on methane leakage is being promised by industry and governments. At the COP28 U.N. climate talks in December, 50 of the world’s largest oil and gas companies pledged to “virtually eliminate” their methane emissions by 2030, Hamburg noted. The European Union in November passed a law that will place “maximum methane intensity values” on fossil gas imports starting in 2030, putting pressure on global suppliers to reduce leaks if they want to continue selling their products in Europe.

In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency has proposed rules to impose fines on methane emitters in the oil and gas industry, in keeping with a provision of 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act that penalizes emissions above a certain threshold. And in December, the EPA issued final rules on limiting methane emissions from existing oil and gas operations, including a role for third-party monitors like MethaneSat to report methane “super-emitters” — sources of massive methane leaks — and spur regulatory action.

Accurate and comprehensive measurements are necessary to attain these targets and mandates, Hamburg said. “Achieving real results means that government, civil society and industry need to know how much methane is coming from where, who is responsible for those emissions and how those emissions are changing over time,” he said. “We need the data on a global scale.”

That’s where Google will step in, said Yael Maguire, head of the search giant’s Geo Sustainability team. Over the past two years, Google has been working with EDF and MethaneSat to develop a “dynamic methane map that we will make available to the public later this year,” he said during Monday’s briefing.

EDF and Google researchers will use Google’s cloud-computing resources to analyze MethaneSat data to identify leaks and measure their intensity, Maguire said. Google is also adapting its machine-learning and artificial-intelligence capabilities developed for identifying buildings, trees and other landmarks from space to “build a comprehensive map of oil and gas infrastructure around the world based on visible satellite imagery,” he said — a valuable source of information on an industry that can be resistant to providing asset data to regulators.

“Once those maps are lined up, we expect people will be able to have a far better understanding of the types of machinery that contribute most to methane leaks,” Maguire said. These maps and underlying data will be available later this year on MethaneSat’s website and from Google Earth Engine, the company’s environmental-monitoring platform used by researchers to “detect trends and understand correlations between human activity and its environmental impact.”

The work between Google and EDF on MethaneSat is part of a broader set of methane-emissions monitoring efforts by researchers, governments, nonprofits and companies. At the COP28 climate summit, Bloomberg Philanthropies pledged $40 million to support what Hamburg described as an “independent watchdog effort” to track the progress of emissions-reduction pledges that companies in the oil and gas industry made at the event.

MethaneSat will bring new technology to the table, he said. Its sensors can detect methane at concentrations of 2 to 3 parts per billion, down to resolutions of about 100 meters by 400 meters. That’s a much tighter resolution than the methane detection provided by the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel satellite, which nonetheless has been able to detect gigantic methane plumes in oil and gas basins in Central Asia and North Africa in the past three years, he said.

At the same time, MethaneSat can scan 200-kilometer-wide swaths of Earth as it passes overhead, he said. That combination of detail and scope will allow it to “see widespread emissions — those that are across large areas and that other satellites can see — as well as spot problems where other satellites aren’t looking.”

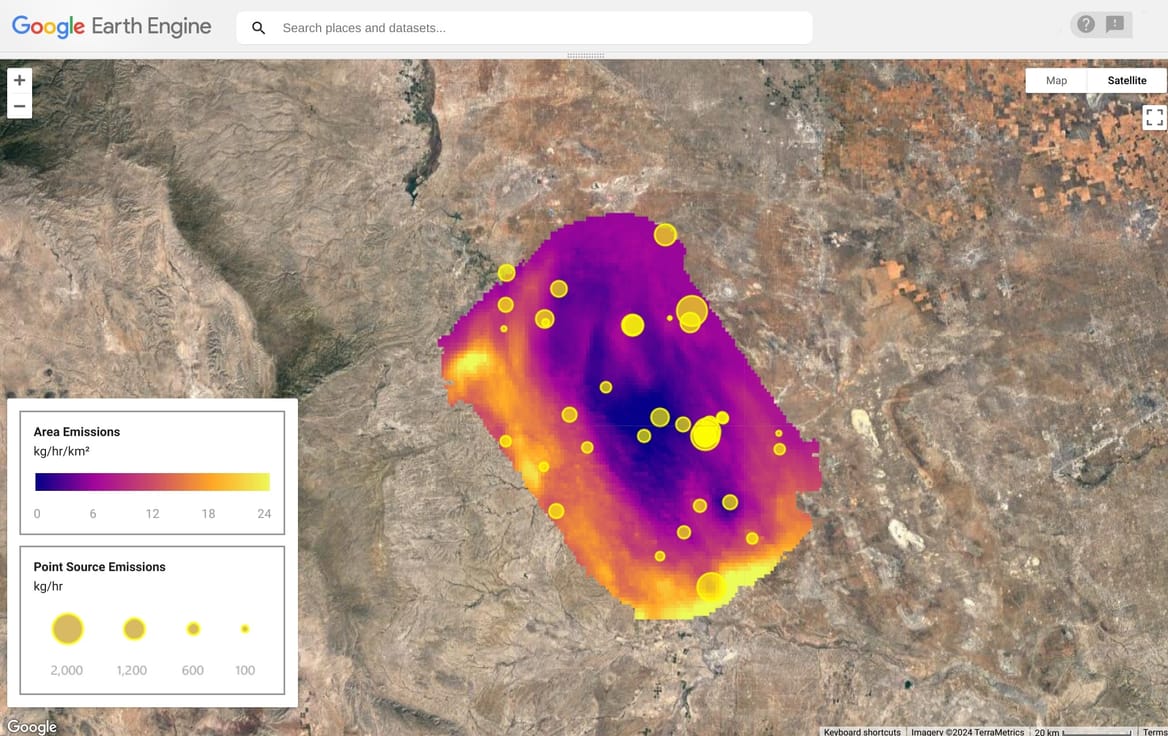

This image, taken from a scan using MethaneSat’s sensors in an airplane flying over the Permian Basin, the major oil- and gas-producing region in West Texas and eastern New Mexico, shows the combination of area emissions and point-source emissions that the sensor can capture.

EDF’s work with Google is also enabling the use of MethaneSat data to detect not only the concentration of methane in the atmosphere but also its “flux,” he said — the volumes of methane leaking and their change over time. That’s important information for government regulators seeking to quantify leakage rates to impose penalties or measure industry mitigation efforts, he noted. “We’re telling everyone the information they need to take action, as opposed to scientific information that requires further processing.”

Hamburg pointed to other satellite, aerial and ground-based monitoring technologies that can provide more fine-grained data on which parts of oil and gas infrastructure are the source of individual leaks, so that “any individual company or actor in a specific spot can make a repair.”

This granular monitoring is being provided today by Canadian-based company GHGSat, which can focus its sensors to collect data from a point on the Earth as small as roughly 25 meters square. It will be aided by Carbon Mapper, a joint effort of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, the California Air Resources Board, private satellite company Planet, and universities and nonprofit partners including RMI and Bloomberg Philanthropies. (Canary Media is an independent affiliate of RMI.)

Later this year, Carbon Mapper plans to launch into orbit two satellites that will be able to deliver 30-meter-square resolution of point-source methane emissions.

“What Carbon Mapper is focused on is how to discover and isolate super-emitters,” Riley Duren, CEO of the public-private consortium, told Canary Media in a December interview.

Duren compared Carbon Mapper to “a collection of telephoto lenses, zooming in to give you a single view.” MethaneSat, by comparison, is “regional accounting, wall to wall, all the emissions in the Permian Basin or Uinta Basin,” or other oil- and gas-producing regions, he said.

“This has to be a system of systems,” he added. “No one technology will solve this.”

MethaneSat has spent $88 million on the design, construction and launch planning for its first satellite, Hamburg said. The work is funded by a $100 million grant from the Bezos Earth Fund, the philanthropic organization launched by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos.

MethaneSat’s data will be open to analysis from “scientists around the world to validate, to make sure that everybody understands what it can do and what it can’t do,” he added.

Maguire noted that the data from Google Earth Engine, including the MethaneSat data it will make available later this year, is “available to researchers, nonprofits and academic institutions for free.” He noted that oil and gas companies will also be able to access the data to inform their own methane leak mitigation efforts. While Google doesn’t have “any information to share at this point” about if or how it might charge companies for that data, “our goal is to make sure that this information is as broadly accessible as possible.”

As for how regulators might make use of MethaneSat data, Hamburg said the organization is “working with the global community of scientists and talking with governments about how to utilize these data to effectively drive the change they’re looking to drive.” He declined to provide specifics on what those conversations with governments have entailed. “I wouldn’t call them formal talks, but active talks,” he said.

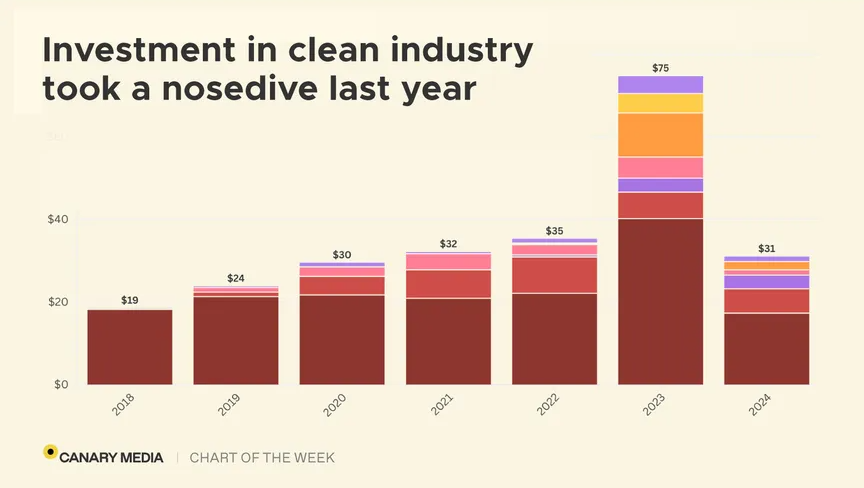

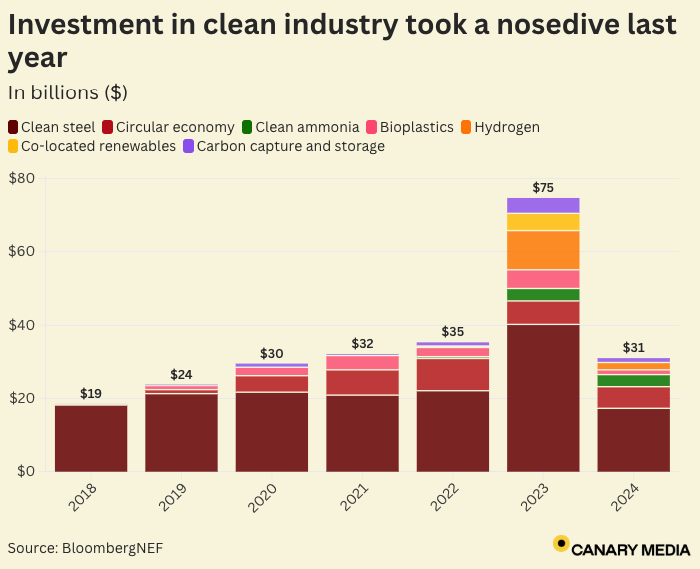

Canary Media’s chart of the week translates crucial data about the clean energy transition into a visual format.

Global investment in efforts to decarbonize heavy industries totaled just $31 billion in 2024, marking a tough year for areas including hydrogen-based steelmaking and carbon capture and storage.

Money for clean industry–related projects fell by nearly 60% last year compared with 2023 — even as investment in the broader energy transition grew to a record $2.1 trillion in 2024, per BloombergNEF.

The diverging outcomes reflect a “two-speed transition” emerging in markets around the world, according to the research firm. The vast majority of today’s energy-transition investment is flowing to more established technologies, such as renewable energy, electric vehicles, energy storage, and power grids.

Meanwhile, efforts to slash planet-warming emissions from heavy industrial sectors — including steel, ammonia, chemicals, and cement — continue to face more fundamental challenges around affordability, maturity, and scalability.

Clean steel projects took the biggest hit in financial commitments, with investment falling to around $17.3 billion in 2024, down from $40.2 billion the previous year, BNEF found.

The category includes new furnaces that can use hydrogen instead of coal to produce iron for steelmaking. Green hydrogen made from renewables remained costly and in scarce supply, leading producers like Europe’s ArcelorMittal to delay making planned investments in hydrogen-based projects. Electric arc furnaces — which turn scrap metal and fresh iron into high-strength steel using electricity — are also considered clean steel projects. Mainland China saw a sharp decline in funding for new electric furnaces as steel demand withered among its automotive and construction industries.

Investment held flat in 2024 for new facilities that use “low-emissions hydrogen” instead of fossil gas to produce ammonia, a compound that’s mainly used in fertilizer but could be turned into fuel for cargo ships and heavy-duty machinery. However, funding declined last year for circular economy projects that recycle plastics, paper, and aluminum, as well as for bio-based plastics production.

BNEF found that, unlike in 2023, few developers of new clean steel and ammonia facilities allocated capital for “co-located” hydrogen plants and renewable energy installations. Likewise, fewer commitments were made to install carbon capture and storage units on polluting facilities like cement factories and chemical refineries.

Whether these investment trends will continue in 2025 depends largely “on a few crucial policy developments in key markets,” Allen Tom Abraham, head of sustainable materials research at BNEF, told Canary Media.

In the United States, companies are awaiting more clarity on the future of federal incentives for industrial decarbonization. The Biden administration previously directed billions of dollars in congressionally mandated funding to support cutting-edge manufacturing technologies and boost demand for low-carbon construction materials — money that is now entangled in President Donald Trump’s federal spending freeze.

Investors are also watching to see what unfolds this month in the European Union. Policymakers are poised to adopt a “clean industrial deal” to help the region’s heavily emitting sectors like steel, cement, and chemicals to slash emissions while remaining competitive. And in China, the government is drafting new rules aimed at easing the country’s overcapacity of steel production, which could impact the deployment of new electric arc furnaces.

“Positive developments on these initiatives could boost clean-industry investment commitments in 2025,” Abraham said.

Since launching in 2019, the U.S. startup Brimstone has positioned itself as a pioneering producer of low-carbon cement. The company’s technology can make the essential material without using any limestone — the carbon-rich rock that, when heated up in fiery kilns, releases huge amounts of planet-warming gases into the air.

Now, Brimstone is looking to use its same process to supply another emissions-intensive industry: aluminum production.

The Oakland, California-based company sources carbon-free rocks that are widely available in the United States but are primarily used today as aggregate for building and road construction. Brimstone pulverizes those rocks and adds chemical agents to leach out valuable minerals. Certain compounds are then heated in a rotary kiln to make industry-standard cement.

Last month, Brimstone announced that its novel approach can also yield alumina, which is the main component of aluminum — the lightweight metal found in everything from household appliances and smartphones to buildings, bridges, and airplanes. Aluminum is also a key ingredient in many clean energy technologies, such as solar panels, heat pumps, power cables, and electric vehicles.

Alumina production today involves extracting and refining a reddish clay ore called bauxite from a handful of countries using environmentally destructive methods. The United States imports nearly all of the alumina it needs to feed its giant, energy-hungry smelters. Over half that supply comes from Brazil, with Australia, Jamaica, and Canada providing most of the rest.

Brimstone says its approach could reduce or supplant the need to scrape bauxite from overseas mines, a process that generates copious amounts of toxic waste. Instead, the company aims to supply U.S. aluminum smelters by sourcing common calcium silicate rocks from domestic quarries and by using chemicals that can be more efficiently recycled than bauxite.

The strategy might also help the six-year-old startup navigate the fraught early period that many newcomers face when trying to break into giant, incumbent industries. Cement is a fairly cheap and abundant material, and the construction sector is inherently wary of deviating from tried-and-true — if carbon-intensive — practices. But the U.S. makes relatively little smelter-grade alumina, despite the essential role it plays in the country’s economy.

“Alumina is a very high-value product that allows us to get into the market…and be very investable in the beginning,” Cody Finke, Brimstone’s co-founder and CEO, told Canary Media. He said that producing alumina could help his team “bridge that valley of death” as it works to scale low-carbon production of cement, which he described as a “larger but lower economic driving force” for the business.

The company, which has raised more than $60 million in venture funding, is slated to open a pilot plant in Oakland later this year that will produce alumina alongside Portland cement — the product that comprises the vast majority of cement made today — and supplementary cementitious materials. Brimstone also plans to build a $378 million commercial demonstration plant by the end of the decade, the site for which is still being decided.

Brimstone is expanding its scope during an especially dynamic period for the aluminum sector.

In recent decades, U.S. aluminum producers have significantly reduced domestic production in response to spiking energy prices and increased competition from China. That in turn has reduced alumina demand from U.S. smelters — which dissolve the alumina in a molten salt called cryolite, then heat and melt it to make aluminum metal. From 2019 to 2023, U.S. alumina imports fell by nearly 33% as manufacturers closed or curtailed their operations.

President Donald Trump has called for imposing fresh tariffs on U.S. aluminum, copper, and steel imports as a way to “bring production back to our country,” and his administration this week imposed or threatened duties on imports from Canada, Mexico, and China, a sweeping action that affects aluminum products. Industry analysts told Reuters that aluminum tariffs would result in higher costs for U.S. consumers, at least until domestic output ramps back up. The country-focused tariffs have already sparked volatility across commodities markets.

At the same time, however, Trump is trying to block federal investments that could boost domestic production of both aluminum and alumina.

Century Aluminum, for example, is set to receive up to $500 million from the U.S. Department of Energy to build the nation’s first new smelter in 45 years. The Biden administration finalized the award on January 15 as part of its larger initiative to slash emissions from industrial manufacturing. Century’s “green smelter” — the location of which hasn’t been announced — will purportedly emit 75% less carbon dioxide than traditional smelters, thanks to its use of carbon-free energy and energy-efficient designs.

The DOE award is currently entangled in Trump’s freeze on tens of billions of dollars in congressionally mandated climate and energy spending. Brimstone is also affected by the pause. In December, the DOE awarded Brimstone up to $189 million to cover half the cost of its planned commercial demonstration plant.

Brimstone declined to comment on the federal funding fracas, which remains in flux even though federal courts have ordered the flow of investment to resume.

Despite the policy uncertainty, there are still potential upsides to making alumina from alternatives to bauxite and within the United States.

Producing alumina using less environmentally intensive techniques — and supplying that material to smelters powered by clean energy — would help lower emissions across the U.S. supply chain and provide much-needed metal for domestic manufacturers. Lessening the country’s reliance on imports could also help insulate the United States from supply chain disruptions and national security risks, according to a 2018 report by the U.S. Department of Commerce.

“Aluminum is a linchpin of domestic aerospace, defense, and automotive applications,” Kevin Kramer, a former executive for U.S. aluminum maker Alcoa who is now a Brimstone senior advisor, said in a statement. “Establishing a new alumina source stateside is vital, and Brimstone’s 100% U.S.-based solution is exactly what the industry needs.”

Three U.S. states — Alabama, Arkansas, and Georgia — mine small amounts of bauxite for chemical and industrial applications. The nation’s single alumina refinery, located in Louisiana, uses imported bauxite to make alumina for aluminum smelting. But most of the world’s alumina production happens in other countries with much larger bauxite deposits.

Other types of minerals and clays also contain alumina, though the modern industry only deals with bauxite. That’s because of “the relatively straightforward nature of extracting bauxite, combined with its commercial abundance,” Adam Merrill, a mineral commodity specialist at the U.S. Geological Survey, said by email. Nearly all commercially produced alumina uses the Bayer process, which involves dissolving bauxite in a high-temperature caustic solution and filtering it to remove impurities.

“Today, the process is used much in the same way as when it was patented in 1888,” he added.

Merrill said that, aside from Brimstone, he isn’t aware of other current research efforts that involve using calcium silicate rocks for alumina production. Earlier studies in the mid-20th century pointed to the fact that silicates contain relatively tiny quantities of alumina — meaning producers would have to dig up substantially more rocks to match what they’d get from bauxite.

Finke said that Brimstone’s answer to this challenge is “co-production,” something he said the industry hasn’t tried before in a meaningful way.

“We’re not just taking the bit of alumina that’s in this and then throwing the rest out,” he said, holding up a small chunk of the silicate rock basalt. “We’re additionally making Portland cement and supplementary cementitious materials. That’s really what our insight was.”

Brimstone plans to mine rocks from existing surface quarries across the United States. At its future commercial demonstration plant, about 20% of its total product will be smelter-grade alumina, with the remaining materials turned into inputs for concrete.

“This would be the first time that alumina is produced from a rock quarry in the United States in a generation,” Finke said of the facility.

OIL & GAS: Colorado regulators consider blocking an oil and gas firm from operating in the state, seizing $317,000 in reclamation bonds and adding its 107 aging wells to the orphaned well program. (Colorado Sun)

CLIMATE: California lawmakers introduce legislation that would allow climate change-related disaster victims and insurance companies to sue fossil fuel companies for damages. (Associated Press)

BATTERIES: California researchers find unusually high concentrations of toxic metals in wetlands downwind of the Moss Landing battery energy storage facility that caught fire recently. (Mercury News)

SOLAR: Wyoming lawmakers advance a bill that would open the door to slashing net metering compensation for rooftop solar after it was changed to exempt existing arrays. (WyoFile)

UTILITIES:

POLITICS:

NUCLEAR:

GRID: Southern New Mexico utility El Paso Electric joins SPP’s day-ahead regional power market. (news release)

COMMENTARY: