The United States hasn’t built a new coal-burning steel mill in nearly half a century. Stricter environmental regulations shifted some of that production overseas, while the latest steel plants adopted newer and cleaner technologies. But seven factories with blast furnaces remain, and they are contributing to poor air quality in the cities where they are located.

Those cities rank among the top 25 with the worst air in the U.S. for at least one of the two most widespread types of pollution, according to new data from the American Lung Association.

The research measured ozone and particulate matter, and when analyzed alongside data on emissions from the blast furnaces, reveal a strong correlation.

“These facilities are some of the biggest emitters of the pollution the American Lung Association’s report is measuring,” said Hilary Lewis, the steel director at the climate research group Industrious Labs, who recently compared the American Lung Association data with her group’s prior research on pollution from steel factories.

“Transitioning these coal-burning furnaces to cleaner alternatives reduces those emissions,” she added. “This is a key step that these communities can take toward getting off the worst-25 list and moving toward cleaner air.”

Last fall, Industrious Labs published the first facility-by-facility breakdown of emissions from every coal-based U.S. steelmaking plant, measuring output of ozone-causing nitrogen oxides (NOx) and PM2.5, the tiny particulate matter increasingly linked to everything from asthma, cancer, and heart disease to ailments afflicting the entire human life cycle: erectile dysfunction, newborns’ congenital heart defects, and dementia.

The analysis ranks the pollution from each steel factory against the emissions from other high-polluting facilities in a given state. Northwest Indiana’s three coal-based steel plants all ranked in the top 10 for NOx and the top five for PM2.5 compared to over 300 other major emitters in the state. The tristate Chicago metropolitan area where those facilities are located ranked 15th for ozone and 13th for year-round particulate matter on the American Lung Association’s list of more than 200 U.S. cities.

Among more than 600 major emitters in Ohio, Cleveland-Cliffs’ Middletown Works plant ranked ninth on Industrious Labs’ list for NOx and sixth for PM2.5. The Cincinnati region where it’s located ranked 14th out of 208 U.S. metropolitan areas for annual particle pollution. The company’s plant in Cleveland fell in 15th place for NOx and seventh for PM2.5, potentially helping drive its home city to ninth place on the American Lung Association’s nationwide list of 208 metropolitan areas with the worst annual particle pollution.

While Cleveland-Cliffs’ other location in Dearborn, Michigan, was only the 42nd-worst emitter of NOx in that state, compared with more than 600 other major polluters, the plant came in sixth for PM2.5 on Industrious Labs’ list — directly mirroring its spot in sixth place on the American Lung Association’s list of U.S. locations with the worst annual particle pollution.

In Pennsylvania, ranked against more than 700 of the state’s biggest polluters, U.S. Steel’s Edgar Thomson Works facility similarly took 40th place on Industrious Labs’ list for NOx, but 21st for PM2.5. On the American Lung Association’s list, the Pittsburgh area where it’s located came in 12th for the worst annual particle pollution nationwide.

“It just points to the fact that coal-based steelmaking is harmful to our health, and we need to be taking more action today to clean up these mills,” Lewis said.

The Trump administration is considering slashing federal programs designed to help steel giants such as Cleveland-Cliffs and Nucor Corp. clean up operations by investing in new equipment like electric arc furnaces to replace the old coal-fired units, the newest of which was built in 1980.

“The transition is at risk,” Lewis said. “All the threats to federal funding for things like modernizing American manufacturing do put the future of clean steel at risk.”

Worse yet, the American Lung Association data doesn’t even capture the full extent of the pollution, said Jack Weinberg, the steel adviser for Gary Advocates for Responsible Development, a nonprofit that advocates for upgrading the equipment at northwest Indiana’s mills.

“The monitoring data seems to understate the problem,” he said.

Last year, the Environmental Protection Agency issued new rules aimed at requiring steelmakers to clean up “unmeasured fugitive emissions” — air pollution emitted when opening valves, or from leaks, that companies had not previously counted in reports to regulators. In March, however, the Trump administration invited companies to apply for full presidential exemptions from the rule for two years. Earlier this month, U.S. Steel became the first major American steelmaker to announce in a regulatory filing that it took President Donald Trump up on his offer. Cleveland-Cliffs and Nucor did not respond to emails asking whether they would join U.S. Steel.

Emissions from U.S. Steel’s Gary Works plant in Indiana are likely linked to as many as 114 premature deaths, 48 emergency room visits, and almost 32,000 asthma attacks each year, according to Industrious Labs’ October analysis, which uses the EPA’s CO-Benefits Risk Assessment model.

“Anecdotally, and I think more accurately,” Weinberg said, “people believe the pollution is affecting their health.”

The Trump administration appears poised to cancel billions of dollars of federal funding meant to help U.S. industries convert to cleaner alternatives to burning fossil fuels.

States can’t match the federal government’s spending power, but there are steps they can take to reduce industry’s emissions, support jobs and economic growth in places burdened by industrial pollution, and help prepare U.S. companies for global markets increasingly demanding lower-carbon commodities and products.

So says a March report from think tank RMI and environmental advocacy organization Evergreen Action that examined the industrial decarbonization plans of 25 states and Puerto Rico. The authors came up with a list of recommendations — and warnings — for states aiming to keep up the momentum on industrial decarbonization.

To be clear, “states can’t just look at what other states are doing and copy it,” said Molly Freed, RMI senior associate and co-author of the report. “What works in a steel and cement state is not going to be effective somewhere that’s canning and bottling stuff.”

But some common lessons can be drawn, she said. The first is not to try and recreate the federal government’s “massive capital grants,” namely, the $6 billion awarded to sites from steel mills to snack factories under the Inflation Reduction Act’s Industrial Demonstrations Program, which is now potentially on the Trump administration’s chopping block.

“States don’t have the initial funding to do that — and they have to balance their budgets every year, so it’s fundamentally not a good format for them,” Freed said.

That’s too bad, because many industrial companies rely on “first mover” public financing to lower the risk of making big investments, said Melissa Hulting, director of industrial decarbonization at the think tank Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. “Early adopters want help with these initial capital costs.” That’s particularly true of certain heavy industries like steel and cement, which have massive capital assets like blast furnaces and cement kilns that will need to be replaced or significantly retrofitted to cut emissions.

But other strategies represent lower-hanging fruit — in particular, replacing fossil-fueled boilers with industrial heat pumps and electric boilers, said Jeffrey Rissman, industry program director at the think tank Energy Innovation.

These technologies are well-suited to electrifying steam heating for food and beverage processing, chemicals production, pulp and paper mills, and other low-temperature processes that make up roughly 30% of U.S. industrial thermal energy demands.

Heat pumps, especially, are far more efficient at converting energy into heat than fossil-fueled boilers, Rissman said. These technologies are already being deployed today and can save companies money compared to fossil-fueled systems in some applications.

“It’s not like we need to solve fundamental engineering challenges here,” he said.

Putting some public money into the up-front costs of electrification could certainly help move things forward, Rissman said. And in some cases, states may still have access to federal dollars to make that happen.

Take the $4.3 billion issued to 25 state, local, and tribal governments through the Climate Pollution Reduction Grants program. That’s one of many Inflation Reduction Act initiatives that had funding frozen in the early weeks of the Trump administration but which have since seen dollars begin flowing again after court orders demanded a restart.

The largest of the industrial decarbonization projects funded by those grants is Pennsylvania’s $396 million Reducing Industrial Sector Emissions program, which is currently accepting applications for everything from electrification, energy efficiency, and process-emissions reductions to on-site renewable energy, low-carbon fuels, and efforts to cut fugitive methane emissions.

Industry is Pennsylvania’s top-emitting sector, responsible for about 30% of statewide emissions, Louie Krak, infrastructure implementation coordinator at the state Department of Environmental Protection, said at a January webinar hosted by the policy institute Center for American Progress.

About 60% of that industrial climate pollution comes from the iron and steel industry, which is a much tougher sector to cut emissions from than lower-heat industrial processes, RMI and Evergreen Action’s report notes. “My advice is, take advantage of federal resources while they’re still around,” Krak said.

That includes smaller-scale federal funding sources, he added. For example, the Department of Energy’s Industrial Training and Assessment Centers program provides grants of up to $300,000 to help small and medium-sized manufacturers implement energy-efficiency projects. That’s ”not an insignificant amount,” Krak said.

A handful of states are looking at spending their own money to boost industrial decarbonization. One way to do that is to tap into state and regional programs that collect fees from polluting industries, such as California’s greenhouse gas cap-and-trade program, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative encompassing 11 Northeastern states, and Washington state’s cap-and-invest program, RMI and Evergreen Action’s report notes.

In California, lawmakers are considering the state’s greenhouse gas reduction fund as a source of money for AB 1280, a bill that proposes expanding programs that support factory electrification and thermal energy storage. One existing initiative that the bill would extend has already directed about $90 million to such projects over the last few years, said Teresa Cheng, California director at Industrious Labs, an advocacy group that supports the legislation.

“This is even more necessary now that federal support has backslid,” Cheng said. Roughly 35,000 polluting industrial facilities now pay into the greenhouse gas fund, and “that money should go back into cleaning up those facilities, commensurate with their polluting profile,” she said.

Another funding avenue proposed by AB 1280 is low-interest loans from the state’s Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank, Cheng said. RMI and Evergreen Action’s report highlights the role that state-backed “green banks” — entities tasked with lending to projects that reduce carbon emissions and air pollution — could play in reducing capital costs for industrial decarbonization.

That could eventually include part of the $20 billion in green bank funding created by the Inflation Reduction Act that has been frozen by the Trump administration and is now being fought over in court. Regardless of the outcome of that dispute, state green banks still have their own money to lend, Rissman noted.

“Buy clean” mandates now in place in nine states, which require state agencies to purchase concrete, steel, and other industrial outputs that are made via lower-carbon processes and using lower-carbon inputs, can further incentivize industries to invest in decarbonization, Rissman said.

Those programs can also provide reporting and compliance structures that companies will need to meet demands for lower-carbon products from corporate buyers, he said. And U.S. firms that export to Europe will be looking to avoid the looming Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism fees on high-carbon imports, set to go into effect in the coming years.

States have regulatory “sticks” they can use to back up the “carrots” of grants, loans, and other incentives for industrial decarbonization. Cap-and-trade or cap-and-invest programs impose costs on polluting industries, for example. Or states can implement rules like the ones passed by Southern California air regulators, which require industrial and commercial customers to replace fossil-fueled water heaters, boilers, and process heating with electric systems within the next decade, Cheng said.

Colorado has both carrots and sticks in place, Wil Mannes, senior program manager of industrial decarbonization initiatives for the Colorado Energy Office, said during January’s webinar. The state passed a climate law in 2021 that set emissions limits on industrial facilities, with rules mandating a 20% reduction in those emissions by 2030 compared to 2015 levels. But it has also opened a $168 million competitive tax credit program and a $25 million grant program for industrial facilities to install improvements that reduce greenhouse gases, which means Colorado is “not heavily dependent on federal support for what we already have in the works,” Mannes said.

“Future of gas” proceedings are another way to spur industrial electrification, said Yong Kwon, senior policy advisor for the Sierra Club’s Living Economy program. California, Colorado, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York are among the states that have launched these discussions to craft long-term plans for reducing customers’ reliance on fossil gas delivered through utility pipelines.

In Illinois, state regulators and other stakeholders are considering proposals for industrial pilot projects that try out different rate structures for companies that switch from gas to electricity, Kwon said. “What if we selected a demonstration site and funded the facility to adopt the technologies, and also worked with utilities to provide them with preferential rates based on studies we’ve done? What would be the result of that, both on public health and on the cost to the industrial user?”

Regulations and up-front financing are both important policy levers. But widespread industrial decarbonization won’t take off unless companies are confident that the investments they’re making will eventually pencil out financially.

“The operational costs are really key,” Hulting said. “If we can get those down, I think we’ll see a lot of implementation happening because these electrified technologies are largely more efficient. It’s an energy-efficiency boost.”

Electric industrial heating faces a core challenge in the U.S. — the spark gap, or the cost difference between fossil gas and electricity. Cheap domestic gas supplies have undercut the economics of industrial electrification over the past two decades, and while gas prices have been rising over recent months, so have electricity costs.

Underneath these broad averages lie significant regional differences, however. Low spark gaps have spurred electric industrial heating investments in certain parts of the country, according to the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, which tracks such projects across the U.S. And most utilities offer industrial rates and pricing structures that can shift the balance toward electrification.

Narrowing the spark gap down to where it encourages industrial electrification relies on two important variables, Kwon said — “making electricity cheaper and making gas more expensive.” Policies that drive up gas costs aren’t exactly a political winner, however. So industrial electrification advocates have focused on making electricity cheaper.

One way to do that is to “give industry access to wholesale electricity rates,” he said. Over the long run, increasingly cheaper renewable energy will drive down electricity costs at large, he explained. But power generated by solar and wind is already quite cheap when it exceeds grid demand. In fact, grid operators are being forced to curtail excess renewable energy at certain times of the year in sun- and wind-rich parts of the country, which sometimes see wholesale electricity prices drop into negative territory.

That’s why industrial electrification proponents are eager for states to create routes for industrial customers to access these cheap wholesale prices, rather than remaining on the retail utility rates that shield customers from these price swings. Access to bulk electricity price differentials is particularly essential for making the business case for thermal-energy storage technologies, which convert electricity to heat and store it for long durations.

In return, big industrial customers can act similarly to utility-scale batteries on the grid, Kwon said — storing excess power when prices are low and using it to reduce their grid demands when power is scarce. That’s already happening in Northern European countries such as Denmark, where variable electricity rates that offer inexpensive off-peak pricing encourage industries to use and store ample wind power, he said. “That’s essential — and that’s a place where we hope states will pick up.”

Just how this concept can be applied depends on what kind of utility rates and energy market structures different states have, Rissman said. For decades, utilities have negotiated special rate structures with particularly large and power-hungry facilities, such as steel furnaces and aluminum smelters. And competitive energy markets like those in Texas, or across some Northeastern and Midwestern states, allow large customers to contract with retail energy providers in ways that let them access wholesale energy market prices, he said.

But these arrangements are largely kept private since they constitute a competitive advantage for the industries that are getting them, he noted. What’s more, rate programs still need to protect factories or facilities from being exposed to the enormous price spikes that can occur at times of power shortage or grid emergency — at least, for all but the handful of industrial players willing to take the risks involved. At the same time, wholesale pricing structures shouldn’t allow industrial customers to avoid paying their fair share of power grid investments or other costs that are bundled into retail rates.

In California, advocates have proposed regulations to allow industrial decarbonization projects to access low-cost renewable energy through some kind of exposure to or pass-through of the state’s wholesale energy market, Cheng said. Last year, state regulators launched a proceeding to explore the potential for such “flexible” rate structures for large industrial companies, she noted. But “it’s pretty early on — we don’t have the answers yet.”

It isn’t easy to trace the flows of electricity across a high-voltage transmission grid that spans 15 states from Louisiana to North Dakota. It’s harder still to differentiate the clean electrons from the dirty ones.

But doing so is necessary for states, companies, and other entities to track real progress toward decarbonization goals. Ultimately, it can be done — so long as you have the right data sources and the willingness to conduct some tricky analysis on power plant emissions and how power moves on the grid.

Just ask the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO), the country’s largest grid operator by geography, and Singularity Energy, a startup developing open-source carbon emissions accounting software. In March, the partners unveiled a “consumed emissions” dashboard, revealing the carbon footprint of electricity within MISO regions, states, and even individual counties, measured on an hour-by-hour basis.

That data is useful for utilities offering “green tariff” programs that promise climate-focused customers a certain share of renewable or carbon-free energy. It also helps states with zero-carbon or renewable energy targets determine the emissions impacts of importing power from out of state versus shuttering fossil-fuel power plants and building clean generation within their own borders.

Those were the two use cases detailed by Jordan Bakke, MISO’s director of strategic insights and assessments, during an April 23 workshop. “Our members and states are pursuing emissions goals both on their own behalf and on behalf of end customers,” he said. “The request that has been given to MISO is to fill that need for temporal, spatial, and timely granularity of emission estimations across our footprint.”

Greg Miller, research and policy lead at Singularity, said similar approaches could help companies that have contracted with wind and solar farms or nuclear power plants to determine how much of that carbon-free power is actually reaching their data centers, factories, and office buildings from hour to hour. That’s a big deal for corporate clean-energy buyers like Google and Microsoft that have committed to serving a growing amount of their enormous power needs with carbon-free electricity.

Singularity is one of many companies working on providing these increasingly complex grid-emissions calculations.

Software providers such as Electricity Maps, Flexidao, and Kevala are tracking power plant emissions and energy flows across swaths of Europe and North America. Companies like REsurety and WattTime have built “marginal emissions” methods to calculate the impact of clean energy generated at different times on regional grids. Major clean energy investors like Quinbrook Infrastructure Partners and HASI are building carbon-tracking methods. And the EnergyTag international consortium has developed “granular certificate” standards to track hourly emissions associated with clean energy contracts.

But MISO’s consumed-emissions dashboard brings a new level of detail, Miller said. “We can’t trace individual electrons, just like we don’t trace water molecules in a river,” he said. “But we can trace larger power flows from generators to the loads where these flows are going.”

Two key data inputs feed Singularity’s emissions outputs for MISO’s new dashboard. The first is its fine-grained estimates of how much carbon is being emitted from individual fossil-fuel power plants — a seemingly simple calculation that’s actually quite complicated to nail down.

“Every generator’s efficiency is described in its heat rate — how much fuel it needs to burn to generate a unit of electricity,” Miller explained. Heat rates change from hour to hour, depending on factors ranging from the outdoor temperature to whether generators are running at maximum efficiency or are just being started up.

Singularity worked with nonprofit and research partners on a project called the Open Grid Emissions initiative to develop a method for calculating those constantly shifting emissions rates using public data and open-source methodologies. In the past year, it has developed a way to use available historical data to estimate those emissions changes in real time, Miller said. Experts in the field can check the methodology themselves “because it’s all modeled off publicly available data.”

The second key source of information at play for MISO’s dashboard is more proprietary — the power-flow data used to assess how much electricity from fossil-fueled power plants and all other sources is reaching the nodes on MISO’s transmission network on an hourly basis. That includes “information about how much power is getting generated and injected to the grid, how much power is getting withdrawn for loads, and the power flows for each transmission line in that network,” Miller said.

The platform that Singularity developed for running that analysis, dubbed CarbonFlow, uses open-source methods to reach its conclusions, he said. But the input data itself is kept confidential, both to protect the competitive interests of the power plant operators in MISO’s energy markets and to comply with federal mandates meant to protect critical infrastructure.

The end result isn’t as complete a picture as some might imagine, Miller emphasized. MISO only tracks power down to the individual substations that convert high-voltage power to lower voltages for use on distribution grids, for example, not to individual customers.

And while the dashboard’s emissions data will be made available on a near-real-time basis at the regional and state level, users have to wait a month after the end of each quarter to look at the hourly data for counties. That’s to avoid revealing operational information about fossil-fueled power plants in those counties to competitors, at least in timeframes that would allow them to act on it in ways that could give them unfair advantages.

Nonetheless, publicly accessible data at the hourly and county level is breaking new ground in the world of grid carbon accounting, Miller said. “This may be for only one region in the U.S. But it proves it’s possible to calculate this data — and other grid operators can do it too, if this data were required more broadly in accounting standards.”

Kathleen Spees, a principal with consultancy The Brattle Group, would like to see MISO and Singularity’s approach picked up by more grid operators. “At the least, they have to start providing the data,” she said.

Brattle was hired by the Illinois Commerce Commission to help develop the state’s Renewable Energy Access Plan, a road map for how the state can meet its mandate to reach 100% carbon-free power by 2045. Illinois already gets more than half of its power from in-state nuclear plants and is aiming to dramatically expand its use of solar and wind power from both within and outside its borders.

“But Illinois, like many states, is highly interconnected with its neighbors,” Spees said. “You can’t just reduce the fossil emissions in your state and say you’re done.” In fact, “if you ramp down gas in Illinois and ramp up coal somewhere else, that’s counterproductive” to the state’s carbon-cutting goals.

That’s why grid operators must be in the picture. The energy markets they run don’t account for carbon emissions today, although some grid operators are starting to make certain emissions data available to participants. But “over time, they have to create the mechanisms for trade,” Spees said, “so that the states that value green energy and avoiding carbon emissions have valid signals.”

Utilities and regulators need hard data to start translating these commonsense understandings of how grids work into real policy decisions with dollars and cents attached to them, Spees said. “We’re not talking minor academic interest here — we’re talking real money. What fraction of the enormous amount of capital going into our sector can ignore carbon implications? It has to be validated.”

That’s going to be complicated, particularly in Illinois, which is served both by MISO throughout most of the state and by PJM Interconnection, a grid operator serving 13 states from Virginia to the Chicago region. But the work has to start somewhere, and “the contribution that MISO is making here is really pushing the envelope in terms of the technical advance of what they can offer,” she said.

Singularity CEO Wenbo Shi pointed out another key use case for MISO’s data: informing “green tariff” programs that are available in most states. Green tariffs offer customers — usually corporate buyers looking to add clean power — the option to pay higher rates to secure a greater share of renewable or carbon-free electricity than what is available from the utility’s general mix of generation.

But to balance things out, each transfer of clean-power ownership rights from a utility to a customer must then be subtracted from the utility’s mix for other customers, lest it be “double-counted” as the same resource belonging to multiple end users.

“Once you can do that, you know exactly who gets what, and what’s left,” Shi said. “This eliminates the risk of double-counting.” The new MISO dashboard can help utilities make these calculations, he said. To accurately allocate clean electricity to the right customers, utilities must first understand their whole supply mix — and those that are part of a regional grid like MISO also need to factor in the energy that they purchase from the wholesale market.

Singularity has worked with utility Southern Co. to deploy such a system to provide customers with unprecedented visibility into their energy mix and emissions, Shi said. In MISO, one of the first users of the grid operator’s consumed-emissions data-tracking capabilities has been utility Entergy Arkansas, which offers green tariffs for customers such as steelmakers.

To be clear, MISO is explicitly not using its consumed-emissions data to inform “market-based” carbon accounting, Miller said. That’s the term for contractual arrangements that establish ownership of a unit of clean energy, such as the renewable energy certificates created under Greenhouse Gas Protocol Scope 2 Guidance, the gold standard in emissions accounting.

At the same time, the GHG Protocol is in the midst of changes that may make the kind of tracking Singularity is doing quite useful for market-based accounting, Miller noted.

Today, companies can offset emissions associated with their electricity use through clean energy purchases that are averaged out over the course of a year, and which can come from sources far removed from a company’s power-using facilities.

Those loose accounting rules helped enable corporate spending in building more clean energy when solar and wind were rare and expensive, and when linking their generation and delivery to a corporate customer’s actual energy consumption was less important. But clean energy has now become the cheapest and most common source of new grid capacity, which means that when and where new clean energy is being built — and whether it’s actually being used by the facilities of the companies claiming it — matters much more.

The data center boom is pushing these issues to the forefront for utilities and regulators. Data center expansions being proposed to feed the AI ambitions of tech giants are threatening to overwhelm the capacity of power grids in key markets across the country, including states like Wisconsin that lie within MISO’s grid footprint.

These ballooning load forecasts are driving utilities and grid operators to propose fast-tracking new fossil gas-fired power plants. But that threatens to undermine the aggressive clean-energy targets set by Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and other companies driving the data center boom, giving them impetus to seek cleaner options.

Just how the GHG Protocol’s rules on clean electricity accounting should work is a contentious subject, with major clean-energy buyers split on issues such as the well-publicized debate over whether they should aspire to 24/7 clean power at their facilities or invest in projects that will reduce the most emissions.

Singularity hasn’t waded into those debates, Shi said. But the technology that it and competing firms are developing can provide the tools necessary to allow clean-energy buyers and states to go beyond high-level and potentially misleading understandings of their emissions — and get closer to actually measuring those crucial figures.

Singularity is “tracing everything, whether it’s based on power flows or contracted,” Shi added “There are technologies that are being deployed that can solve that problem.”

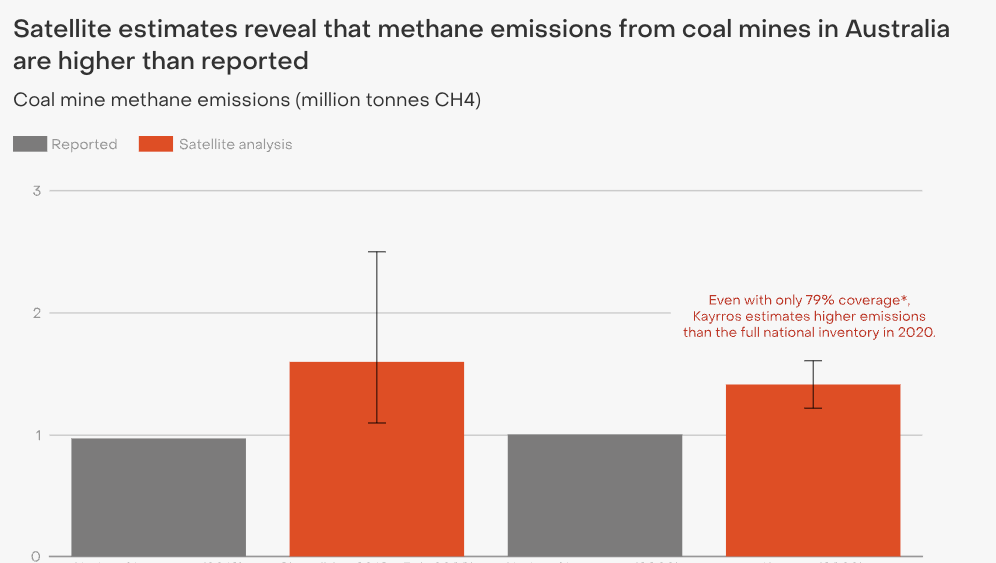

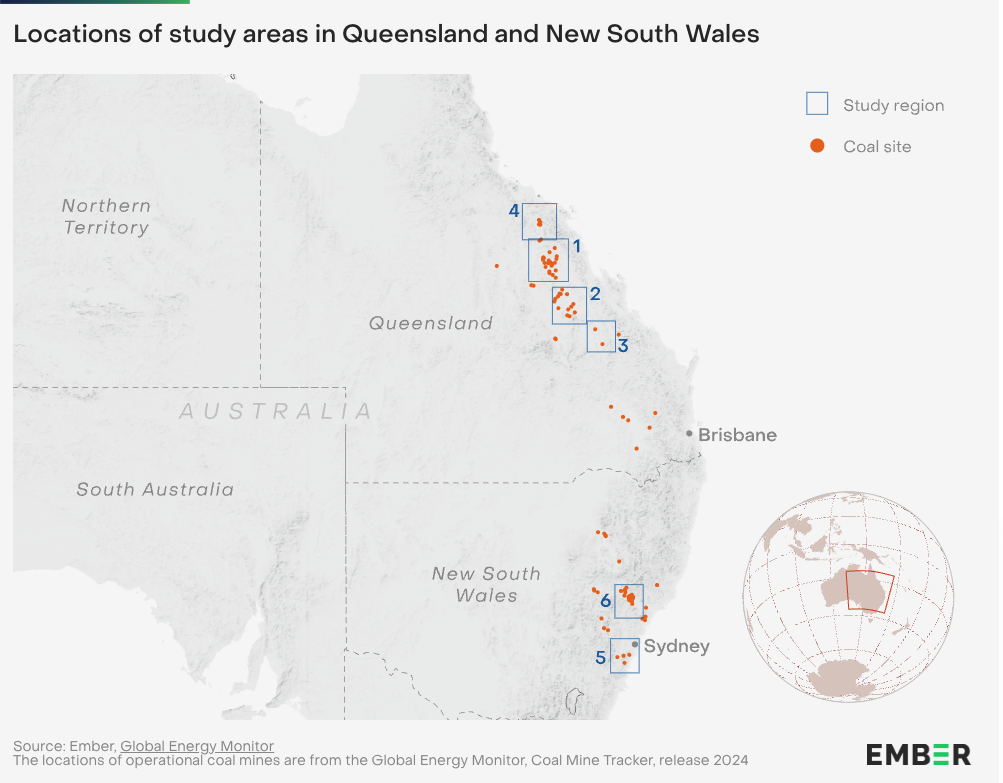

Sydney, 16 April 2025 – A new satellite analysis from global energy think tank Ember has identified 40% greater methane emission from Australia’s coal mines than officially reported. The analysis finds that current reporting methods fail to capture the full scale of emissions, with significant implications for both domestic policy and global steel supply chains.

The collaborative study, based on TROPOMI satellite data analysed by energy intelligence from Kayrros, examined six key coal mining clusters that account for 79% of Australia’s black coal production in Queensland and New South Wales. The analysis, which compared emissions from 2020 and 2021 identified elevated coal mine methane emissions in both states, with a significant discrepancy in New South Wales.

While the study only accounted for two thirds of black coal production in New South Wales, it identified methane emissions within these limited clusters at twice the level that was officially reported state-wide.

Through a comparative assessment of open-cut coal mining in NSW, the study further identified coal mine methane emissions 4-6 times greater than officially reported through company-led estimates.

These findings largely support the diverse array of international and peer-reviewed satellite estimates that have identified considerably higher methane emissions from Australia’s coal mines. This includes a recent aircraft study that identified emissions over Hail Creek mine could be 4 to 5 times than currently reported.

Following a year-long national inquiry into methane measurement approaches in Australia, the Federal government has initiated an Expert Panel to provide advice on atmospheric measurement of fugitive methane emissions in Australia and a departmental review on company-led emissions estimates on open-cut coal mines.

These findings highlight not only the critical importance of these reviews, but the urgency in which Australia needs to improve its emissions reporting, especially within its steel-making coal supply chains.

The study encompassed over 90% of Australia’s metallurgical coal production, a large portion of which is presently exported to the EU. This share of exports will soon be subject to strict emissions reporting requirements under the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Without necessary improvements, these new regulations could jeopardize significant export opportunities.

This discrepancy in emissions reporting points to the risks of relying on self-reported data and underscores the need for more accurate and independent monitoring.

The study also finds that without major changes to Australia’s existing coal mine methane reporting inventory, the country’s policymakers and international steel-making supply chains will remain in the dark about the total scale of Australia’s coal mine methane emissions.

In his first 100 days, President Donald Trump has antagonized the clean energy industry, putting crucial federal funding on ice, rolling back key regulations, and even coming after state climate laws.

This week, Democrat-led states took to the courts to begin fighting back.

On Monday, attorneys general from 17 states and Washington, D.C., filed a lawsuit aimed at protecting the clean energy sector that’s caught most of Trump’s ire: wind.

Trump’s Day 1 executive order paused the approval of new federal leases, permits, and loans for wind farms, and his EPA and Interior Department have gone on to revoke existing permits from one offshore project and order work to stop on another that had already begun at-sea construction.

The suit alleges the president doesn’t have the authority to single-handedly shut down the permitting process — and that his moves threaten thousands of jobs, billions of dollars in investments, and the country’s clean energy transition.

In an interview with Canary Media’s Clare Fieseler, New Jersey Attorney General Matthew Platkin said Trump’s anti-wind orders fly in the face of his “energy dominance” goals, on top of being carried out unconstitutionally.

“This is a time when we’re dealing with rising costs, when everyone agrees we should be increasing domestic energy production,” Platkin said. “It’s flagrantly illegal, but it also just makes no sense.”

Environmental advocate and renewable energy professor Chris Powicki speculated to Massachusetts local news station CAI that Republican-led states may become quiet backers of the suit, given that Trump’s order also targets onshore wind farms, which many of them have benefited from.

A similar coalition of 16 states and D.C. hit the courts again on Wednesday, this time suing the U.S. Transportation Department for withholding billions of dollars for a national electric-vehicle charger buildout. The attorneys general alleged the administration’s move is illegal since the funding was allocated as part of the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law, meaning only Congress has the power to pull it back. A rollback would jeopardize hundreds of charging stations that haven’t yet been built.

Energy Star is Trump’s latest target

President Trump’s attacks on energy efficiency reached new heights this week, as the U.S. EPA reportedly told staffers it’s planning to shut down its Climate Protection Partnerships division and the Energy Star program it houses. If there’s one EPA program you know, it’s probably Energy Star, which uses its signature blue sticker to indicate how much energy — and money — an appliance can save consumers.

Republicans in Congress have also made several moves against energy efficiency in the past few weeks, passing resolutions to undo Biden-era regulations governing commercial refrigerators, water heaters, and other appliances, and to repeal a rule affecting efficiency labeling and certification. More cuts could be on the way as the Trump administration and Congress work to roll back Inflation Reduction Act tax credits — some of which reduce the cost of home efficiency upgrades.

This offshore wind farm is a win for sea life

A new in-depth study of the South Fork offshore wind farm shows fish have nothing to fear when it comes to turbines. Scientists surveyed the seafloor off the Long Island coast before, during, and after the array’s construction and found it had no negative impact on the area’s biological communities. The wind farm also became a makeshift reef for marine invertebrates to latch onto, attracting dozens of fish and shellfish species to feast.

The study is further proof that the installations don’t necessarily pose serious threats to marine life — something President Trump and other offshore wind opponents have repeatedly alleged. And despite ongoing federal animosity toward offshore wind, two developers recently said they’ll continue building. Danish energy company Ørsted said it will move forward with its New York and Rhode Island wind farms, while Canary Media’s Clare Fieseler reported this week that Dominion Energy is pressing on in the waters off Virginia.

Manufacturing at risk: The Trump administration looks to gut the Energy Department’s Industrial Demonstrations Program, putting 26 U.S. manufacturing projects and thousands of jobs at risk. (Canary Media)

IRA uncertainty continues: A Republican Congress member says there’s “a lot of disagreement” in his party over whether to preserve, edit, or repeal Inflation Reduction Act tax credits. (E&E News)

A cleaner rebuild: A new report makes the case that it could be cheaper and quicker to replace Los Angeles buildings destroyed in January’s wildfires with all-electric structures, even after Mayor Karen Bass exempted rebuilds from all-electric building codes. (Canary Media)

Unfair share: As congressional Republicans look to tax EV drivers to make up for lost gas-tax revenue, an analysis shows EV and hybrid-vehicle owners would pay far more under those fees than drivers of gas-powered cars pay in fuel taxes. (Washington Post)

What’s the holdup? Energy analytics firm Enverus finds Texas has some of the shortest wait times for solar and wind projects looking to interconnect to the power grid, while California’s wait times are among the longest. (Forbes)

Oversight, out of mind: The U.S. EPA hasn’t filed any new cases against major polluters under President Trump, and has significantly scaled back minor criminal and civil enforcement cases. (Grist)

The grid’s growing pains: Grid operator PJM Interconnection selects 51 projects, mostly gas-fueled power plants and battery storage facilities, to jump to the head of its interconnection queue as part of an effort to get power online faster. Opponents to a similar plan in the Midwest say it could worsen grid bottlenecks while discouraging cheaper and clean energy. (E&E News, Canary Media)

A salty development: Startup Inlyte Energy looks to commercialize iron-salt battery technology invented in the 1980s, and is launching its first large-scale test with Southern Co., one of the biggest utilities in the U.S. South. (Canary Media)

The Trump administration has launched an all-out assault on American energy-efficiency efforts that have saved consumers billions of dollars and eased the transition away from fossil fuels.

From proposing to eliminate the popular Energy Star and Low Income Home Energy Assistance programs to firing staff and delaying building efficiency standards, President Donald Trump’s moves threaten to upend decades of progress on making appliances and structures do more with less energy.

“Energy efficiency is the best, fastest, cheapest way to lower energy costs,” said Mark Kresowik, senior policy director at the nonprofit American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. “That’s something that, ostensibly, the Trump administration said they want to do.”

Trump’s actions could undercut his own promise to halve energy bills during his first 18 months in office, as well as hamper climate action.

Efficiency is an undersung tool for reducing carbon pollution. If the globe maximized efficiency efforts, it could phase out fossil fuels by 2040, according to nonpartisan clean energy nonprofit RMI. It’s typically the lowest-cost way utilities can meet power needs, a crucial consideration as electricity bills rise around the country. And with electricity demand forecast to climb to record highs due in large part to the rapid expansion of AI data centers, efficiency could take on new importance as a way to get more out of every unit of energy.

One of the most recent and notable moves against efficiency programs is the Environmental Protection Agency’s plan to kill Energy Star. The EPA announced the decision to shutter the program at an all-hands meeting last week, according to The Washington Post, though the agency has not publicly confirmed the decision.

Energy Star is a voluntary program that certifies the most efficient appliances available to American households and businesses. Products that have earned the iconic aqua-blue label span dozens of residential and commercial categories, including data center storage, water heaters, clothes dryers, furnaces, and heat pumps.

The program has been wildly successful. Since 1992, Energy Star has prevented 4 billion metric tons of planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions — equivalent to a year’s pollution from 933 million cars — and helped consumers save more than $500 billion in energy costs. For every dollar the federal government spends on the program, consumers save a whopping $350.

Axing Energy Star would also scramble eligibility for federal and local incentives that require the program’s seal of approval, such as the $2,500 tax credit for home builders.

More than 1,000 companies, building owners, and other organizations have come out in support of Energy Star. “Eliminating it will not serve the American people,” a coalition of appliance manufacturers and industry leaders wrote in a letter to EPA head Lee Zeldin, Inside Climate News reported.

Energy Star isn’t the only federal energy-efficiency program in peril.

In April, the Department of Health and Human Services fired the more than two dozen staff members who administered the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), according to Harvest Public Media. The initiative provided financial support to nearly 6 million households in 2023 across all 50 states and the District of Columbia, helping vulnerable Americans cover utility costs, undertake energy-related home repairs, and make weatherization upgrades that reduce energy bills.

Released in early May, the president’s “skinny” budget proposal for the next fiscal year recommends shuttering the $4 billion program, which in particular helps households with older adults, individuals with disabilities, and children.

Cutting program funding and failing to hire back staff may affect more than energy bills, according to advocates.

“The elimination of the staff administering LIHEAP could have dire, potentially deadly, impacts for folks who will not be able to safely cool their homes as we enter what is predicted to be another historically hot summer,” Amneh Minkara, deputy director of Sierra Club’s building electrification campaign, said in a statement.

President Trump and Congress are also targeting efficiency standards for appliances sold in the U.S. The president just signed four resolutions to undo a handful on Friday.

That’s despite both Democrats and Republicans saying they want appliance standards. According to an April poll by Consumer Reports, 87% of Americans, including four out of five Republicans, agree that new home appliances for sale in the U.S. should be required to achieve a minimum level of efficiency.

Part of the administration’s strategy will likely include simply not enforcing the standards, according to the Appliance Standards Awareness Project. Last month, ProPublica reported that Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency team had “deleted” the consulting contract that the Department of Energy relies on to develop and enforce these rules. But the item subsequently disappeared from DOGE’s online “wall of receipts,” making its status cloudy.

Beyond appliances, the Trump administration is snarling rules for more efficient buildings, too.

In March, the Department of Housing and Urban Development delayed compliance deadlines set by a landmark 2024 measure that requires certain new homes purchased with federally backed mortgages and new HUD-funded apartments to meet updated building energy-efficiency codes. The rule would save single-family households an average of $963 per year on energy bills, according to the agency’s estimates, and affect up to a quarter of new homes nationwide, per RMI. The administration wrote in a recent court filing that it is “actively considering whether to revise or revoke” the rule.

In April, the Department of Energy proposed to indefinitely delay implementing efficiency standards for manufactured homes that would reduce average annual energy costs by $475.

And on May 5, the agency punted by a year the compliance date for a standard that would ensure federal buildings that are built or significantly renovated between this year and 2029 slash on-site fossil-fuel use by 90%. In 2030 and beyond, the standard requires new and renovated federal buildings to be all-electric.

That rule, Energy Star, and many of the other energy-efficiency efforts under threat are congressionally mandated — and not all Republicans are rolling with the administration’s attacks.

In a statement earlier this month, Sen. Susan Collins, a Republican from Maine, said she had “serious objections” to some measures in Trump’s budget blueprint, including the elimination of LIHEAP. Collins, who chairs the Senate Appropriations Committee, noted that “ultimately, it is Congress that holds the power of the purse.”

Corrections were made on May 12, 2025: This story originally misstated that consumers buying heat pumps must purchase Energy Star-certified equipment to qualify for the $2,000 25C federal tax credit. The tax credit does not base eligibility on Energy Star, but rather on the Consortium for Energy Efficiency specifications. The story also originally misstated that a handful of resolutions to undo federal efficiency standards await the president’s signature. President Trump signed the resolutions on May 9, 2025.

The wildfires that ravaged parts of Los Angeles County in January were the most catastrophic in its history. Made worse by climate change, the disaster caused as much as $131 billion worth of damage and destroyed more than 16,000 homes and other properties.

In the name of a speedy recovery, LA Mayor Karen Bass, a Democrat, issued a broad executive order that same month, exempting replacement structures from a city ordinance that requires new buildings to be all-electric. (The waived code only applies to communities within the city boundaries, not to the entirety of LA County.)

The order effectively swept aside one of the city’s most important tools for eliminating its reliance on planet-warming fossil fuels, the continued use of which makes such climate-related disasters more likely in the future. Buildings accounted for more than 40% of LA’s carbon pollution in 2022 — more than any other sector — and are estimated to contribute a quarter of California’s total emissions.

The mayor’s move reflects a tacit assumption that has been echoed even in the State Assembly: that rebuilding with gas, which many of the affected buildings had used, must be the easiest path for recovering communities.

But a new report flips that premise on its head. Citing available research and expert interviews, a team at the University of California, Berkeley’s Center for Law, Energy, & the Environment argues that all-electric construction is likely to be the fastest and most cost-effective way to rebuild after the LA fires.

A key reason is that two systems are more complicated to rebuild than one. “We’re going to install electricity infrastructure in all buildings regardless,” said Kasia Kosmala-Dahlbeck, climate research fellow at the UC Berkeley center. “So it’s really about whether you also install a second system” that delivers fracked gas, also commonly known as natural gas.

Such dual-fuel construction has historically been the norm in California, but all-electric construction avoids the added time and cost of hooking up gas infrastructure. That often requires property owners to submit a separate service request to the gas utility; install gas meters, pipes, and ductwork; and coordinate gas safety checks, according to the authors.

The team expects all-electric rebuilds to not only deliver better indoor air quality for occupants but to be easier on people’s wallets. Their report cites a 2019 study that estimates building a new all-electric home in most parts of California costs about $3,000 to $10,000 less than building a home that’s also equipped with gas. The UC Berkeley team notes, though, that potential savings for LA County’s wildfire-hit neighborhoods are likely lower since existing gas infrastructure, much of it underground, was largely unscathed.

All-electric new homes in California that skip gas-burning appliances for much more efficient electric heat-pump heaters and ACs, water heaters, and clothes dryers, as well as induction stoves, are also likely to slash energy bills, per the report. An April analysis by climate think tank RMI provides support, finding that single-family households switching from gas furnaces and conventional air conditioners to heat pumps would save about $300 per year on average in LA County.

Kosmala-Dahlbeck points out that people going the all-electric route now will be able to avoid costly and complex retrofits in the future.

“We’ve seen repeatedly that retrofitting later down the line is more expensive than constructing all-electric to begin with,” she said. Upgrading a home’s electrical service alone can cost anywhere from $2,000 to $30,000 and take two months to two years, according to California-based all-electric home developer Redwood Energy.

In the near future, installing a new gas appliance when the old one conks out could be less of an option. Air regulators for the state are developing standards that could bar the sale of new gas furnaces and water heaters starting in 2030. Regulators covering LA County are poised to adopt rules that would discourage new installations of these polluting appliances as soon as 2027.

The report authors recommend that policymakers — including city council members, county supervisors, the mayor’s office, and state legislators and agencies — support an all-electric recovery.

Mayor Bass has already moved in that direction. While her office confirmed that the first executive order waiving all-electric standards remains in effect, she issued another directive on March 21: By later this month, LA departments must develop suggestions to streamline permitting for owners who rebuild with all-electric equipment.

Construction has begun in LA’s Pacific Palisades neighborhood, one of the areas hit hardest by the wildfires. According to the mayor’s office, 20 addresses in the Palisades have been issued permits for rebuilding efforts. Staff noted that the permits don’t have to specify whether a project is all-electric. But some affected residents do plan to rebuild without gas appliances, NPR recently reported.

All-electric new buildings are on the rise across California, according to the California Energy Commission. In 2023, 80% of line extension requests by builders to utilities Pacific Gas & Electric and San Diego Gas & Electric were electric-only.

In general, outside of the fire recovery process, the financial case for building all-electric homes in the state is getting stronger. “We’ve heard from California builders that recent updates to infrastructure rules — combined with a statewide energy code that strongly encourages heat pumps — have shifted the economics of building all-electric new construction,” said Will Vicent, deputy director of the Energy Commission’s building standards efficiency division.

The UC Berkeley team is also encouraging policymakers to bolster incentives and resources that make all-electric rebuilding more affordable. That could look like expanding the Rebuilding Incentives for Sustainable Electric Homes program and the electrification resource and rebate hub The Switch is On. Such investments would line up with LA County and the state’s climate goals to become carbon neutral by 2045.

Jonathan Parfrey, executive director of LA-based nonprofit Climate Resolve and an appointed member of a county commission focused on rebuilding sustainably after the fires, said the report’s findings are important for policymakers to consider as they help people who lost their homes navigate the potentially yearslong process of recovery.

“It’s an enormously traumatic experience, and the first impulse that you have after that terrible loss is a return to normalcy” by trying to rebuild what you once had, said Parfrey, who reviewed the UC Berkeley report before it was publicly released. But “it’s impossible to recapture that home once it’s gone.”

Instead, “there’s the possibility for creating something even superior to what you had before.”

Georgia Power, which expects a boom in power demand from data centers, says it needs to get a lot more electricity online — fast.

So what kind of power plants does the utility intend to rely on to accomplish this? It’s refusing to say, raising concerns that the state’s largest utility is trying to avoid public scrutiny of plans to build huge amounts of expensive, unnecessary, and polluting fossil-fueled infrastructure.

Georgia Power filed its mandatory 20-year plan with state regulators in January. In it, the utility proposes keeping several coal-fired power plants open past their previously planned closure dates. That has already earned it an “F” grade from the Sierra Club.

But the integrated resource plan (IRP) also has few details about the mix of energy sources the utility wants to draw on to supply the new electricity generation it says it needs by 2031. Georgia Power puts that amount at 9.5 gigawatts, which is equal to nearly half of its total current generation capacity. This means stakeholders don’t know to what extent the utility plans to build new fossil-gas power plants versus clean energy and batteries.

That worries environmental and consumer advocates as well as trade groups representing the tech giants whose data center plans are driving Georgia Power’s electricity needs to begin with. For years, these groups have been pressing Georgia Power and the state Public Service Commission to prioritize clean energy, batteries, and other alternatives to fossil-fueled power plants.

Now, they fear Georgia Power’s secretive IRP process may allow the utility to rush through approval of a gas-heavy plan. By keeping its intentions to itself until the last possible moment, Georgia Power is giving the public little time to digest proposals and respond with economic or environmental counterarguments.

It also puts the state’s utility regulators in a bind. The utility says it needs to start building these new power plants ASAP or else grid reliability will suffer. That sense of urgency may give regulators little choice but to approve Georgia Power’s plans as-is.

“It’s very confusing, and it’s very concerning for us to be planning a future of growth without knowing how we’re going to meet it,” said Jennifer Whitfield, senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, one of several groups demanding more information on Georgia Power’s plans. “And that’s the position we’re in until we know more.”

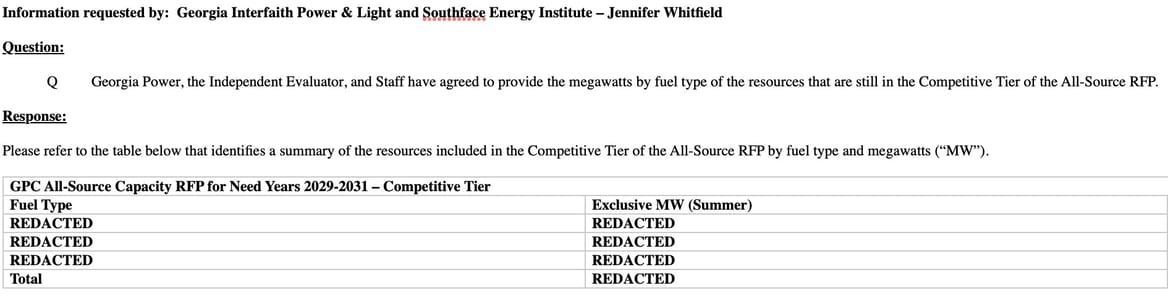

Whitfield brought up the issue at a Public Service Commission hearing last month. Georgia Power’s IRP has identified only 517 megawatts of projects, she pointed out. The utility is seeking out the remaining roughly 9 GW of resources needed by 2031 through an “all-source RFP,” or request for proposals. The process is separate from the IRP — and shrouded in confidentiality.

That’s a problem, Whitfield said at the hearing, because state law requires IRPs to provide “the size and type of facilities” that a utility expects to own or operate over the next 10 years. Yet, in Georgia Power’s current IRP, “95% of the need to fill capacity in Georgia in 2031 is not made available,” she said. “How are we supposed to effectively intervene to judge the economic mix without additional information?”

Jeffrey Grubb, Georgia Power’s director of resource planning, replied at the hearing that those details are, “by commission rule, not publicly available because that could have detrimental impacts on the RFP itself.”

Whitfield argued that Georgia Power should at least disclose what portion of the roughly 9 GW of unidentified resources might consist of fossil gas–fired power plants built by the utility, as opposed to clean power, batteries, or resources built and owned by third-party developers.

Grubb declined to provide that information. “We cannot speak about those because we’re still working on them,” he said.

But Georgia Power is already working on at least one large expansion of fossil-fueled power. In March, the utility applied for state permits to build four gas-fired turbines with a combined generation capacity of about 2.9 GW at the site of the utility’s coal-fired Plant Bowen.

Grubb conceded in the hearing that the utility sought those permits in preparation for possibly building the gas-fired units, which aren’t mentioned in Georgia Power’s IRP.

“We’re not sure if we’ll need all four of those,” he said. “There’s other things that we’re looking at, but I can’t speak more than they are potential resources from that RFP, and that’s why we had to move forward” with filing the permits.

Whitfield asked the Public Service Commission to require Georgia Power to provide more information on the projects being considered in its RFP, including details on fuel type, ownership, and size. Last week, in response to that request, Whitfield received the following document from the utility, which contains nothing but two columns of the word “redacted.”

“It’s difficult to understand any justification for redacting this information,” said Bob Sherrier, a staff attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center. “How can the public meaningfully engage with Georgia Power’s proposed data center plans without any insight into what’s coming?”

Georgia Power spokesperson Jacob Hawkins told Canary Media in an April 18 email that the utility follows “established processes and legal requirements when submitting sensitive or proprietary information that, if made available broadly and publicly, could hurt our ability to negotiate and procure the best value and resources for our customers. Intervenors who sign confidentiality agreements as part of the process have access to much greater and detailed information.”

“We would disagree in the strongest possible terms that we are not following all statutory requirements and state law across the board in these proceedings, period,” Hawkins wrote.

Many states allow utilities to withhold details about the cost or type of resources in all-source RFPs to avoid undermining the competitive bidding process. But what’s uncommon about Georgia Power’s current case is just how much of its future will be dictated by this process.

Georgia Power’s need for new generation has exploded in the past two years, driven largely by a flood of plans to build data centers in the region. The utility has tripled its decade-ahead electricity demand forecasts since 2022. That projected boom in demand has somewhat scrambled the standard processes for utility resource planning, Whitfield told Canary Media.

In its last full-scale IRP in 2022, Georgia Power identified enough resources to cover its needs until 2029, she said. But it also identified an approximately 500 MW gap between demand and supply from 2029 to 2031, and agreed with regulators to launch the all-source RFP to fill it. That all-source RFP process is not subject to the same disclosure rules as an IRP, as it involves competitive bidding between the utility and third-party energy project developers.

Regulators approved an interim IRP last year that allows Georgia Power to build 1.4 GW of fossil-fueled power plants and 500 MW of batteries, and to contract for nearly 1 GW more from other utilities’ coal- and gas-fired power plants, to relieve some of its nearer-term pressures.

But the all-source RFP launched back in 2022 has remained Georgia Power’s main mechanism to get what it needs by 2031, Whitfield said. That’s despite the fact that it was initially meant to cover just 500 MW, a figure nearly 20 times smaller than the 9.5 GW it is now planning to fill via the all-source RFP process.

This has created something of a regulatory shell game in which Georgia Power can contract for the vast majority of its future energy and capacity needs outside the purview of the standard IRP process, said Simon Mahan, executive director of the Southern Renewable Energy Association trade group.

“Many organizations and companies focus exclusively on the IRP, while the ultimate decisions may occur in a totally separate docket, where fewer intervening parties are engaged,” he said.

The battle over Georgia Power’s missing gigawatts comes as the utility has failed to bring as much renewable energy into its resource mix as it previously pledged to.

The utility has about 3 GW of solar, helping to push Georgia into the top 10 states for solar growth. But it’s also been slow to contract with third-party owners of solar and battery projects to meet its power needs. Georgia Power’s 2025 IRP calls for an additional 3.5 GW of renewable energy by the end of 2030, but that plan partially just makes up for the utility’s cancellation of previous clean-power procurements, Mahan noted.

Solar alone can’t meet Georgia Power’s capacity needs, which are driven by demand for electricity for heating in wintertime.

But batteries that can store solar or general grid power could play a more significant role. Regulators approved Georgia Power to add 500 MW of battery storage in last year’s interim IRP, and its 2025 IRP calls for further expanding its energy storage capacity. Mahan noted that much of the solar power being proposed in the state will likely be paired with batteries to enhance its value to Georgia Power’s grid.

Without more information on the contents of the all-source RFP, it’s nearly impossible for environmental groups, consumer advocates, and other stakeholders to know whether Georgia Power is properly weighing renewable alternatives to gas-fired power plants that the utility will build and own itself.

Georgia Power’s commitment to fossil gas and coal — which together made up nearly 60% of its capacity last year — is certainly a problem for the climate. The Sierra Club calculates that the generation mix laid out in Georgia Power’s proposed 2025 IRP would make the utility “one of the top greenhouse gas emitters in the U.S.”

It could be a problem for utility customers, too, who have already seen rates rise significantly in recent years due to Georgia Power’s more than $30 billion expansion of its Vogtle nuclear power plant.

Like most regulated utilities, Georgia Power earns a set rate of profit on investments in power plants, power grids, and other capital assets. It’s also required to allow third-party developers to compete with it to build solar and battery projects — a process that can yield lower costs for its customers but also lower rates of return for the utility.

Regulators have a responsibility to closely monitor the utility’s process for choosing which resources end up winning to ensure those decisions aren’t maximizing Georgia Power’s profits at the expense of its customers, said Patty Durand, a consumer advocate and former Public Service Commission candidate. But she fears regulators will fail to challenge Georgia Power’s assertions on which resources will most cost-effectively meet its grid needs.

“We need to keep stock of how many gigawatts of fossil fuel Georgia Power is building or keeping on the grid because of data centers,” she said. “That is a climate change disaster.”

Durand has also challenged Georgia Power’s load-growth forecasts, noting that the utility has consistently overestimated future electricity demand across the past decade, helping it justify increased spending on profit-earning assets.

“Are utility bills a kitchen-table issue? If they are, these guys are in trouble,” she said. “Data centers are about to make the bills we pay now into a joke.”

Some of the tech giants playing a role in the data center expansion driving Georgia Power’s demand forecasts have similar concerns. Last year, Microsoft challenged the utility on how it models the value of clean energy resources as well as how it forecasts load growth.

Georgia Power also faced pushback from the Clean Energy Buyers Association (CEBA), which represents companies like Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft that are simultaneously planning major data center expansions and striving to decarbonize their energy supplies. In testimony before the Public Service Commission last year, CEBA warned that “some of the new load Georgia Power is forecasting may not materialize if Georgia Power increases the carbon intensity of its resource mix.”

CEBA ended up supporting last year’s interim IRP on the condition that Georgia Power follow through with a promise to offer large industrial and commercial customers new options to bring more carbon-free resources onto the utility’s grid.

Georgia Power’s 2025 IRP lays out a “customer-identified resource” proposal to meet its end of the bargain, said Katie Southworth, CEBA’s deputy director of market and policy innovation for the South and Southeast. In simple terms, the utility would allow big customers to work with third-party developers to build solar, batteries, and other carbon-free resources that they could use to power their data centers and other large facilities. That’s a fairly common practice in parts of the country operating under competitive energy markets — but not in Georgia and most of the U.S. Southeast, where utilities remain vertically integrated.

However, the utility’s plan lacks transparency and certainty about how customer-proposed projects will be assessed and approved, and it limits the scale and scope of resources that big customers can bring to the table. Georgia Power also plans to delay implementation of that program, frustrating CEBA members eager to start searching for potential projects.

Hawkins, the Georgia Power spokesperson, told Canary Media that the utility continues to “incorporate CEBA’s feedback into our program designs, while still ensuring that all Georgia Power customers are protected. Our proposed IRP portfolio of renewable procurements and programs represents a continuation of our steady and measured renewable growth that delivers benefits to all customers.”

In the meantime, Southworth said, CEBA is encouraging Georgia Power customers looking for cleaner energy options to “get involved in the design of the all-source process. That gives us a chance to include other resources that could play a role.”

That may be an option for qualified energy developers active in that competitive procurement. But it remains unclear if or how the Public Service Commission will push Georgia Power to open the hood on that process for consumer advocates and environmental groups that have been denied information thus far.

“This is an exceptionally unusual time in the Georgia energy world for a million reasons, of which this is one. I think this is a hugely important issue,” Whitfield said. The investments being planned today are “going to transform our energy system,” and Georgia Power is conducting that work “without providing critical information about what that new system might look like.”

But time is running short to order more transparency. Georgia Power plans to announce the winning bids for its all-source RFP in July, Whitfield said — the same month that state regulators expect to take their final vote on the IRP.

Electrowinning is a time-tested method for removing impurities from metals, and it’s able to run on clean electricity and at the same temperature as a fresh cup of coffee. Could it help clean up heavy industry by replacing the gigantic coal-fired blast furnaces used to purify iron, a key ingredient in steelmaking?

Sandeep Nijhawan, CEO and cofounder of electrolytic clean-iron technology startup Electra, thinks so. On Thursday, the Boulder, Colorado-based firm announced that it has raised $186 million from investors, including some major players in the trillion-dollar global iron and steel industry, to further test its proposition.

Thursday’s round was led by Capricorn Investment Group and Temasek Holdings, and included previous investors Breakthrough Energy Ventures, Lowercarbon Capital, and S2G Investments. It also included Rio Tinto, Roy Hill, and BHP’s venture capital arm, representing some of the world’s largest iron ore suppliers; leading steelmakers Nucor and Yamato Kogyo; and major iron and steel buyers organizations Interfer Edelstahl Group and Toyota Tsusho Corp., the trading arm of Toyota Group and supplier to Toyota Motor Corp.

“This broad, very sophisticated, strategic investor base gives us a vote of confidence that our solution can potentially be an integral part of the value chain,” Nijhawan said.

The new funding will finance Electra’s first demonstration-scale project, which aims to produce about 500 tonnes of high-purity iron annually when it opens next year — a droplet in the nearly 1.9 billion tonnes of steel produced globally in 2023. The company hopes to have a commercial-scale production site, of undisclosed size and capacity, operational in 2029, Nijhawan said.

Steelmaking accounts for 7% to 9% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and most of those emissions are tied to the process of purifying iron in blast furnaces that burn metallurgical coal at temperatures of around 1,600 degrees Celsius.

Cutting that carbon footprint requires shifting to electric arc furnaces that use electricity to melt a mix of steel scrap and purified iron into new steel. But to clean up the industry, the purified iron going into those furnaces must first be produced in ways that don’t choke the atmosphere.

“We are replacing how iron has been made for centuries,” Nijhawan said. “When you think about that transition, you think about a long-term view of how you create a stable business in that environment.”

Electra’s process is competing against a number of alternative methods for making lower-carbon iron. The most prevalent approach to date — and the one that’s gotten billions of dollars of investment — is direct reduction of iron via hydrogen.

Direct reduced iron is being deployed by the biggest green-steel projects in the world, such as the H2 Green Steel and Hybrit plants in Sweden. But early-stage efforts to build up capacity for hydrogen direct reduced iron in the U.S. have faltered in the face of high costs, lack of commitments from buyers, and more recently, the Trump administration’s U-turn on Biden-era policies supporting industrial decarbonization. The process also requires cost-effective production of carbon-free hydrogen, a challenging prospect in and of itself.

Boston Metal, a spinout of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, aims to decarbonize steelmaking with a very different method known as molten oxide electrolysis, which uses electricity to heat iron ore to blast-furnace temperatures. The startup plans to open its first demonstration plant in 2026. That process avoids carbon emissions but still requires super-high temperatures and hefty electricity inputs.

Electra’s approach, electrowinning, is already used to purify metals such as copper, nickel, and zinc. It works by dissolving iron ores into an aqueous acidic solution to separate iron ions from impurities in the ores, and then electrifying the solution to deposit pure iron onto metal plates.

Electra’s quest to purify iron via electrowinning has faced some key challenges. For example, the company had to figure out how to accelerate the dissolution of iron ore in the solution and how to maintain the purity of the ions collected through the electrowinning process, Quoc Pham, the company’s cofounder and chief technology officer, told Canary Media in 2023. A handful of research consortiums and corporations are pursuing electrowinning iron but using an alkaline rather than an acidic solution.

Electra has produced plates of pure iron in pilot tests. That’s just the first of many steps in proving it can cost-effectively scale up the technology to operate in high-throughput industrial settings using iron ores with a wide mix of chemical compositions, Nijhawan said.

But success on those fronts could unlock a lot of opportunities for Electra investors along the iron and steel value chain, he said — starting with the company’s longest-running strategic investor and top U.S. steelmaker Nucor.

Nucor exclusively uses electric arc furnaces, which require careful calibration of the mix of scrap steel and purified iron going into them to produce different grades of steel for diverse industrial sectors.

Those include the automotive manufacturing market, where advances in electric arc furnaces are overcoming longstanding beliefs that only blast-furnace steel can meet automakers’ quality standards, and where automakers like Hyundai are making multi-billion-dollar investments in the electric equipment.

“We’re seeing a shift in the automotive sector,” Noah Hanners, Nucor’s executive vice president for sheet products, said in a Thursday statement. “As we produce more [electric arc furnace] steel for the automotive market, our demand for sustainable feedstocks like Electra’s product will only continue to grow.”

Electra’s technology can also purify a wide range of iron ores, which could open up new markets for iron-mining giants like those investing in the startup’s latest round, Nijhawan noted. That’s particularly valuable for low-carbon steelmaking since hydrogen direct reduced iron can handle only a narrow range of impurities, which could limit its use to the available supplies of higher-quality ores.

Nijhawan highlighted another distinguishing feature of Electra’s approach — its modularity. A typical steel plant that uses a blast furnace or the direct reduced iron process costs billions of dollars, takes years to build, and involves coordinating the delivery of massive amounts of iron and fuel.

Electra’s electrolytic modules, by contrast, can be deployed at a variety of scales to match supply and demand dynamics in different markets. “One electrical array can go up to 50,000 tons, for example, and you can do that again and again,” he said. “It’s not like you have to go build a 2-million-ton plant to become economically viable.”

That optionality could ease concerns from investors wary of sinking billions of dollars into a single facility using a novel technology, he said. It also allows Electra to test its modules and improve performance and cost in succeeding generations.

Similar dynamics have helped propel solar panels and lithium-ion batteries to the cheapest and most easily deployable energy technology today, he noted. “It helps you to have the same repeat unit that you’re perfecting for quality, for defects — and to learn fast as a result.”

The “Eating the Earth” column explores the connections between the food we eat and the climate we live in.

NEW YORK — Our food system generates one-third of our greenhouse gas emissions, and the human race has made almost no progress reducing them. Except in New York City’s public hospitals.

Before the city deployed an innovative new strategy two years ago to shrink its “carbon foodprint,” 99% of its patient meals included meat. Now more than half are vegetarian, generating 36% fewer emissions. While vegan activists have mostly failed to get us to ditch meat through education campaigns and yelling, and biotech entrepreneurs have mostly failed to convert us to plant-based substitutes designed to mimic meat, bureaucrats working for embattled Mayor Eric Adams have engineered a radical dietary shift.

Sitting in her bed in the surgical ward at Brooklyn’s Kings County Hospital, pointing at a clean plate that minutes earlier was covered with mushroom stroganoff, 60-year-old Pamela Sumlin-Gambil revealed the secret of the city’s success.