Power demand from data centers threatens to scuttle utility decarbonization goals, push grid infrastructure to the brink, and drive up electricity costs for everyday customers already struggling to pay their bills.

But a new report identifies a strategy that utility planners can take to avoid these problems while still providing data centers with the massive amounts of power they require. They simply need to convince data centers to use less electricity from time to time — and they need to do so early in the utility planning process, when it’s still a win-win for both developers and utilities.

The report, based on research conducted by analysis firms GridLab and Telos Energy, used NV Energy, Nevada’s biggest utility, as a case study. According to its numbers, NV Energy could save hundreds of millions of dollars and defer hundreds of megawatts of “new firm capacity needs” — i.e., fossil-gas-fired power plants — if the proposed new data centers in its territory agree to be flexible.

But all these benefits are predicated on that flexibility being “factored into resource planning early on rather than being an afterthought,” Priya Sreedharan, a senior program director at GridLab, said during a webinar last week. Without that vital early work, utilities will lock in multibillion-dollar investments to manage the grid peaks that they assume inflexible data centers will cause.

And once those plans are in motion, the chief incentive for data-center developers to commit to being flexible with their energy — getting faster grid interconnections — will evaporate.

Grid planners and utilities face an unprecedented wave of power demand as tech giants race to build data centers to support their artificial-intelligence ambitions. In many cases, plans for new data centers — the largest of which can use as much power as a small city — are spurring the construction of new fossil-fueled power plants, putting decarbonization further out of reach and raising costs for consumers.

The GridLab–Telos Energy report adds to a growing body of work identifying flexibility as a way for data centers to connect to the grid quickly without causing utility costs and emissions to skyrocket.

To become flexible, data centers will need to invest in gas-fired generators, batteries, solar panels, or other resources to supply their own power needs during times of peak demand. Or they’ll need to take on the technically complex task of ramping down power-hungry computing processes when the grid is under the greatest stress.

Data centers won’t do that just to save money on their electric bills, said Derek Stenclik, founding partner at Telos Energy. But they might do it to speed up when they get connected to the grid — or, in data-center parlance, “time to power.”

In some parts of the country, data centers are struggling to get the grid connections they need even though they’re willing to pay extremely high power prices to secure them. That’s because building the power plants and grid infrastructure to meet their demands can take years.

“If you go to a prospective data center and say, ‘Hey, with our queue, it’s going to take five years for us to bring on new resources to build the transmission to get to you and you can wait five years, or we can interconnect you in two years if you’re willing to curtail 10 to 12 hours a year,’ the answer there will be much, much different than if you’re asking them after they’ve been designed,” Stenclik said.

GridLab and Telos Energy chose NV Energy as a test case for a few reasons.

First, the utility has a ton of new data centers trying to connect to its grid — enough to add 2 gigawatts of peak load by 2030 — and keeping up with that demand will be expensive. Former NV Energy CEO Doug Cannon told the Nevada Appeal in February that the utility may need “billions of dollars of investment” to “double, triple, even quadruple the size of the total electric grid” in the northern Nevada region where most of the new data centers are being built.

Second, GridLab and Telos were ready to model the impact of flexible data centers in the region because they served as experts for groups intervening in the utility’s 2024 integrated resource plan. Utilities, regulators, and other stakeholders use these plans to figure out what mix of generation resources are required to meet future grid needs.

NV Energy’s latest plan calls for converting a coal-fired power plant in northern Nevada to run on fossil gas, rather than building solar and batteries at the site, as it had previously proposed — a decision opponents are formally challenging because they argue it will increase customer costs. Like many U.S. utilities, NV Energy faces backlash over rising rates, including an overcharging scandal that coincided with Cannon’s resignation in May.

Similar load-growth pressures driven by the AI data-center boom are pushing utilities across the country to plan far more new gas-fired power plants, at great cost not only to the climate but also to customers, who will pay higher bills to cover the cost of building and fueling them. Data centers are already pushing up electricity rates in some parts of the country.

Flexible data centers could make a big dent in these costs by allowing utilities to rely more on solar and batteries, which are less costly and faster to build than gas plants. GridLab and Telos Energy’s fact sheet on their analysis of NV Energy found that “even modest levels of load flexibility can yield large capacity savings.”

Specifically, the report found that 1 GW of data-center flexibility could defer from 665 to 865 megawatts of new firm capacity needs and save $300 million to $400 million through 2050. Those savings would come from alleviating the utility’s need to build more gas-fired power plants and from substituting more “lower cost ‘energy’ focused resources such as solar plus storage.”

Getting data centers to commit to energy-flexible operations could make a huge difference across the country, according to Tyler Norris, a Duke University doctoral fellow who is a former solar developer and special adviser at the Department of Energy. He co-authored an analysis released in February that found nearly 100 gigawatts of existing capacity on U.S. grids for data centers that can commit to a certain level of flexibility.

Getting data centers to ease off during specific hours of the year is eminently feasible, Norris argued in an August presentation to state utility regulators. Data centers’ “capacity utilization” rates — a measure of how much of their total potential power demand they’re using across all hours of the year — are all over the map, with some analyses estimating rates as low as 50%.

But utility planners can’t build a grid around estimates, and data-center developers don’t have good reasons to commit to using less power unless they see a clear reward.

“Not even the most sophisticated data center owner-operators necessarily know what their utilization rates and load shapes will look like,” Norris wrote in an August blog post. “Their preference is generally to maintain maximal optionality” — that is, to demand as much access to as much always-available power as they can get.

Nor do data centers have a clear path to achieve the kind of flexibility that utility planners may demand, said Ben Hertz-Shargel, global head of grid-edge research for analytics firm Wood Mackenzie.

“There are two main ways to make data centers flexible,” Hertz-Shargel said. “You can make the compute flexible. Or you can use backup generation, which is almost always diesel today.”

But data centers can’t run megawatts of noisy, polluting, and expensive diesel generators without running afoul of air-quality regulations and enraging neighbors, he said. True flexibility will require more novel options like gas-fired generators and batteries charged from the grid or on-site solar systems, he added.

Meanwhile, flexible computing is in its early stages. Of the major tech giants, only Google has actively engaged with utilities to shift computing to match grid needs. Experiments from companies such as Emerald AI have shown “some auspicious results,” Hertz-Shargel said. “But for the industry to count on that, it’s too early.”

Utilities and regulators will also need to adapt how they plan for serving flexible data centers, Telos Energy’s Stenclik said. Today, they’re taking on rising data-center costs in a multitude of ways, from crafting special tariffs to govern their impact to allowing tech giants to contract for 24/7 clean energy resources in order to supply their power demands. But he wasn’t aware of any utility that has undertaken a real-world version of the kind of demand-side flexibility analysis that GridLab and Telos did.

Utilities should start working on it, given the alternatives, he said. “We’re leading to higher total capacity needs. We’ve seen huge challenges on the supply chain. We’re out five, six years from new gas turbines now,” he estimated.

“I think there’s a ton of latent flexibility,” he concluded. “We’re just asking for it at the wrong time. If you ask for it when they’re already built and designed and on the system, the answer is going to be no. If we trade speed to interconnect for flexibility, I think the answer will absolutely be yes.”

Investment in cleantech startups is tracking toward the lowest level in years. But Base Power shrugged off the market trends and just raised $1 billion to turbocharge its home battery buildout.

The colossal Series C funding round comes only six months after it raised $200 million in an April Series B. Addition led the latest round, which brought back all previous investors, including Andreessen Horowitz and Valor Equity Partners. The company’s valuation now stands at $4 billion after receiving the new investment, Base Power founder and CEO Zach Dell said.

The pace and scale of those investments put the Austin, Texas–based firm in a league of its own among clean energy startups this year — beating out even the outlandish $863 million that Commonwealth Fusion Systems raised in August. Dell says his company’s traction comes down to a very clear value proposition: It’s potentially the fastest way to expand on-demand grid power at a time when everyone wants more of it.

“Right now, we’re in a capacity crunch — everyone needs capacity,” Dell said. “We install capacity faster and cheaper than really anyone out there.”

The U.S. is going through the fastest electricity demand growth in decades, as AI data centers proliferate, more factories open up, and customers purchase electric vehicles. Utilities have long maintained a skeptical stance toward startups’ plans to turn home energy devices into substantial forces on the grid; now, Dell said, they’re not just willing but “more excited than ever” to have that conversation.

The key to Base Power’s model is finding households in Texas who want cheap electricity with the benefit of backup power. The company becomes their retail power provider and installs one or two unusually large batteries on-site. Base owns the batteries, and the customers pay an installation fee starting at $695 and a small monthly rate instead of purchasing them for many thousands of dollars. Then the startup aggregates this dispersed fleet of batteries to essentially create miniature power plants it can profit from in the state’s competitive energy market.

The batteries earn money through simple arbitrage: They charge up when wind or solar production pushes prices down and then discharge when demand and prices spike. Base Power also earned certification to deliver ancillary services, which are rapid-fire adjustments to maintain grid reliability, for which batteries are uniquely suited. The company has already maxed out the 20 megawatts it can bid through the Aggregate Distributed Energy Resource pilot, a virtual-power-plant program, and is pushing for the cap to be raised, Dell said.

Base Power has begun selling its services to regulated utilities so that they can help their customers with backup power and free up more grid capacity. And Dell is scoping out other geographical markets where the rules could allow the Base Power model to grow. But for now, Texas is the ideal place to start. It not only has the competitive market run by the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, or ERCOT, but it is also awash in more utility-scale solar and wind than any other state, enhancing the value of battery-based arbitrage.

When Dell spoke to Canary Media for the previous fundraise, he employed 100 people, and his in-house teams were installing 20 home battery systems per day, for a total of about 10 megawatt-hours in March. Now Base Power employs 250 people and installs double that rate. A year from now, Dell wants to install 100 megawatt-hours per month.

That’s a brash goal for a 2-year-old company. But Base Power has actually followed through on its goals, a rare distinction among buzzy cleantech startups. In April, Dell had promised 100 megawatt-hours of cumulative installations by midsummer; he hit that target and is now approaching 150 megawatt-hours.

The firm has also been planning to move from contract manufacturing for its bespoke battery enclosures to in-house manufacturing. In April, Dell said he planned to break ground on a factory near Austin by the end of the year. Now the company has leased the old Austin American-Statesman newspaper headquarters in the heart of town and has begun moving in manufacturing equipment.

“It’s a 90,000-square-foot empty warehouse that happens to be right across the street from our HQ. There’s massive amounts of benefits you get from colocating engineering and manufacturing — having the engineers be really close to the factory, being able to walk the line and make iterations in real time.”

This factory will take imported battery cells and build the modules, packs, and power electronics needed to turn them into large home-battery products. The plan is to start manufacturing in the first quarter of 2026 and ramp up to 4 gigawatt-hours per year of production capacity, Dell said. This supply chain strategy also shores up compliance with new federal rules limiting tax credits for batteries that contain too much content from China.

Base Power is already finalizing a location for a “much, much larger” facility outside Austin to continue growing its manufacturing capacity.

Other startups have opted for “capital light” strategies to get solar or batteries into the hands of customers. Base Power, in contrast, went capital-heavy, fronting the money to design, own, and install the batteries with the expectation of making future profits on their capacity. It’s too soon to know how that business bet will play out over years, but Dell indicated the early returns were attractive.

“It’s hard to raise a billion dollars without that,” he noted. “The math is indeed mathing.”

What is A-CAES?

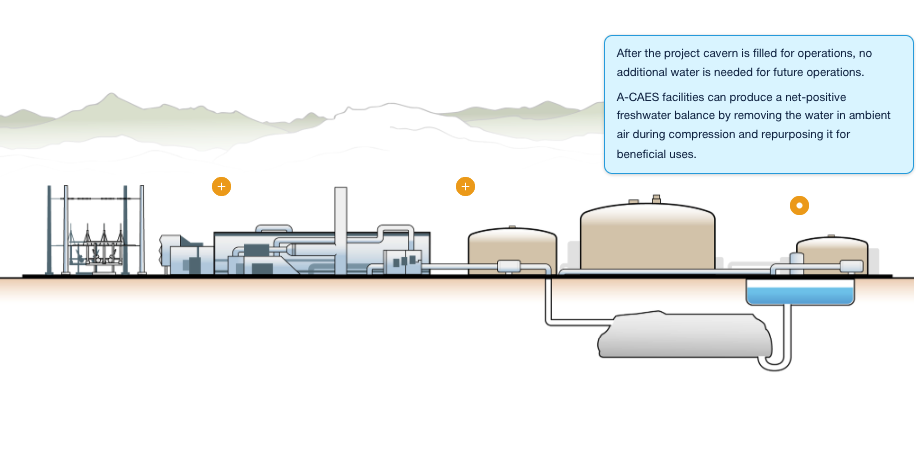

Advanced compressed air energy storage (A-CAES) is a technology that stores energy by compressing air and later releasing it to generate electricity. It is an enhanced form of traditional compressed air energy storage (CAES), which has been in use in California and other parts of the world for decades. Hydrostor’s key advancement is that A-CAES captures and stores the heat generated during the compression phase and uses it to reheat the air during expansion, which significantly improves efficiency while eliminating the use of fossil fuels for daily operations. This patented technology makes it a much more environmentally friendly and cost-effective method for large-scale, long-duration energy storage.

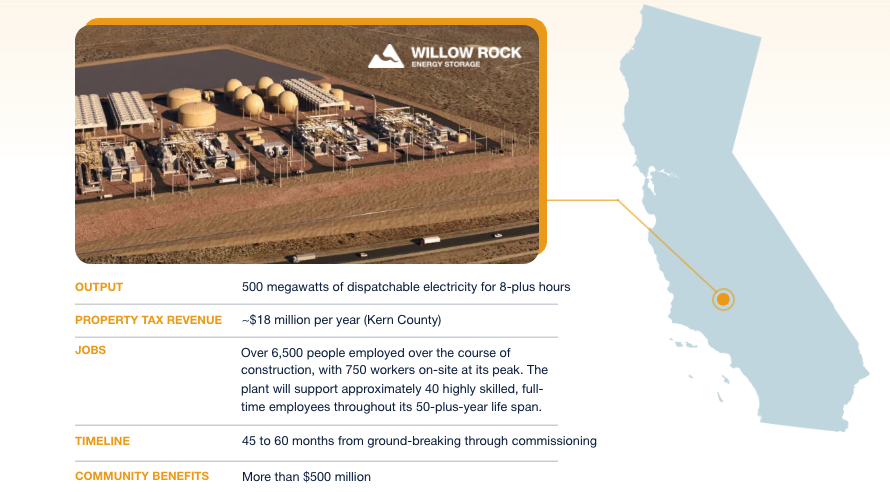

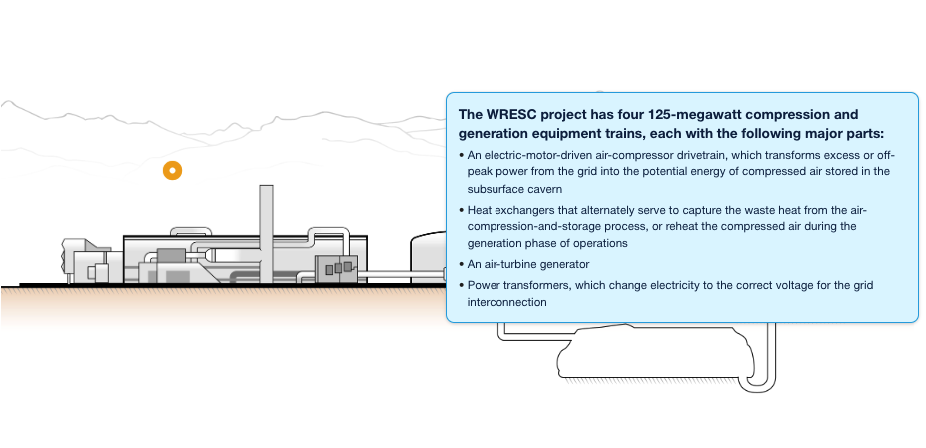

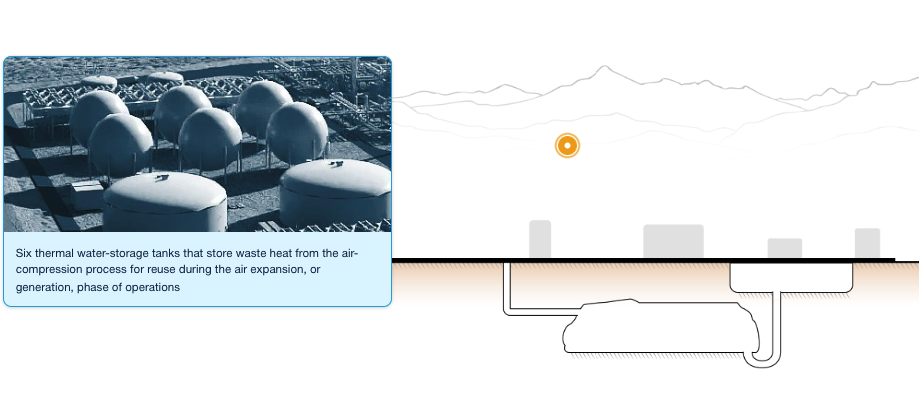

Take a look at how Hydrostor’s Willow Rock Energy Storage Center (WRESC) project in Kern County, California, is contributing to the state’s energy priorities:

From drawing board to full operation: a phased approach

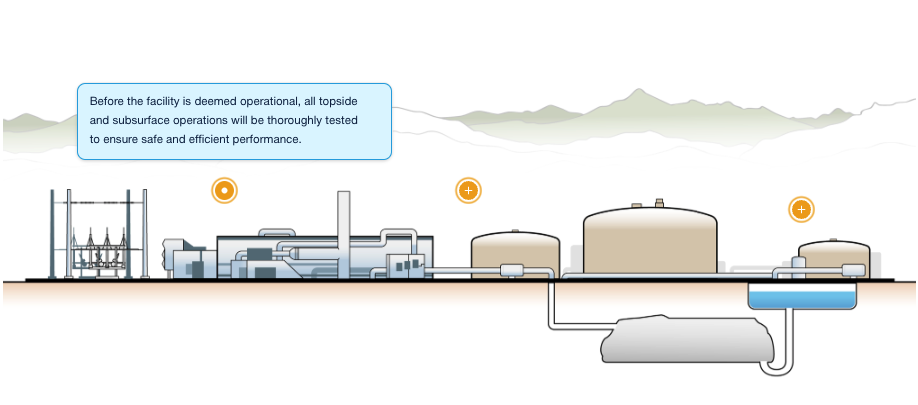

Construction of the Willow Rock project is anticipated to take 60 months from the time the project breaks ground until it goes online. The construction work will take place in six phases:

Preconstruction

Before any physical work can begin on a project of this scale, Hydrostor does substantial preliminary work to ensure there are minimal impacts to the surrounding communities and environment. Preconstruction assessments completed for the Willow Rock Energy Storage Center evaluated potential impacts on air quality, cultural resources, geologic conditions, soil health, water quality, and other factors and included recommendations on how to mitigate those impacts. An extensive permitting process will involve consulting with the local community, state agencies, and federal agencies before construction begins. A-CAES facilities have a smaller physical and environmental footprint than other energy infrastructure, using five to 20 times less water than pumped hydro and more than 10 times less land than solar for an equivalent amount of energy.

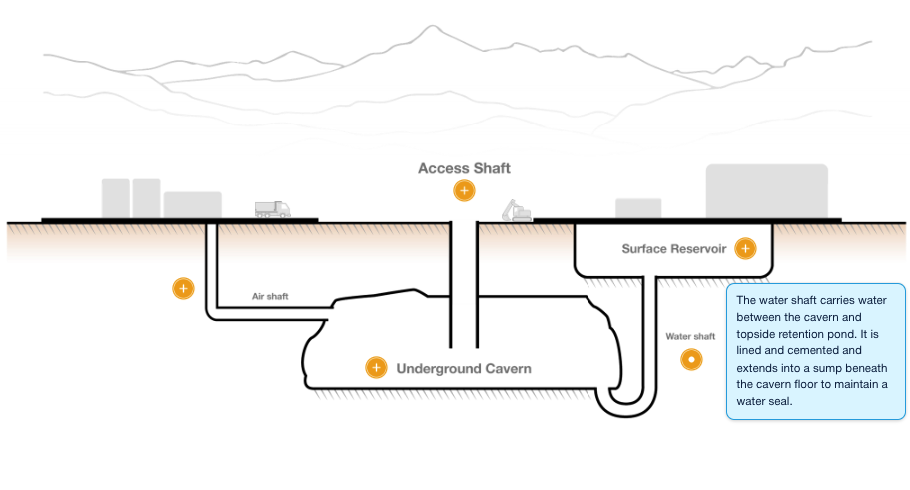

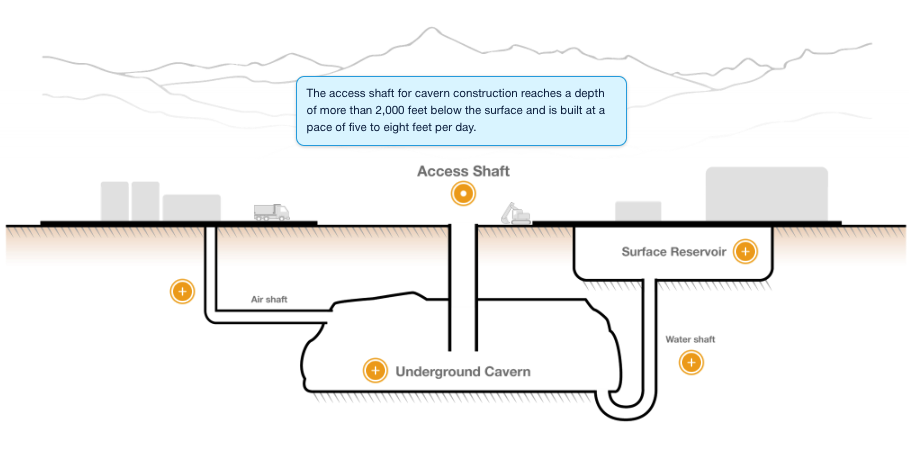

Cavern Construction

The first parts of an A-CAES facility to be built are the underground cavern and its associated air, water, and construction shafts. The storage cavern is constructed in bedrock approximately 2,000 to 2,500 feet belowground. This subsurface work is the most time-consuming portion of construction, taking roughly three years.

Topside Construction

Once the subsurface construction is underway, topside construction begins. This phase includes installing turbines, thermal storage tanks, and the rest of the facility’s aboveground equipment in addition to constructing the transmission line.

Transmission

The Willow Rock Energy Storage Center is located near the project’s transmission interconnection point, the SCE Whirlwind Substation, thereby reducing the time, cost, and complexity of building the transmission infrastructure.

Once construction is complete, all project equipment will be rigorously tested for safety and efficiency before Willow Rock officially begins providing reliable power to millions of Californians.

Willow Rock’s 50-Plus Year Commercial Life Span

Once operational, A-CAES facilities like Willow Rock — unlike many other energy storage technologies — will operate with zero efficiency loss over its expected commercial life span of 50 years or more. This means Hydrostor’s work in host communities—and the jobs it creates to operate each facility—are long-term commitments that provide lasting local and regional benefits.

A-CAES projects' flexible siting, energy density, environmental attributes, and community benefits make them an excellent fit for many regions across the U.S. Learn more about Hydrostor's growing project pipeline here.

California Governor Gavin Newsom has vetoed three bills that aimed to boost the use of virtual power plants, undermining an opportunity to decrease the state’s fast-rising electricity costs and increase its grid reliability.

On Friday, Newsom vetoed AB 44, AB 740, and SB 541, which were passed by large majorities in the state legislature last month. Each bill proposed a distinct approach to expanding the state’s use of rooftop solar, backup batteries, electric vehicles, smart thermostats, and other customer-owned energy technologies.

In three separate statements, Newsom argued that the bills would complicate state regulators’ existing efforts to use those technologies to meet clean energy and grid reliability goals.

The moves come as utility costs reach crisis levels in California; its residents now pay roughly twice the U.S. average for their power.

In response, Newsom did sign into law a package of bills aimed at combating cost increases at the state’s three major utilities: Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric. But some supporters of the virtual power plant (VPP) bills speculated that these same utilities were to blame for Newsom’s vetoing legislation that could have further driven down costs, as the governor has received significant campaign contributions from PG&E and the policies would have eaten into utility profits.

“These vetoes effectively stall progress on key distributed energy and affordability strategies,” said Kurt Johnson, community energy resilience directorat the Climate Center, a nonprofit group. “Policies and programs in California continue to be killed because they threaten the economic interests of California’s powerful investor-owned utilities.”

Izzy Gardon, Newsom’s director of communications, declined to comment on these critiques in an email response to Canary Media, saying, “The Governor’s veto messages speak for themselves.”

But Edson Perez, who leads California legislative and political engagement for clean-energy trade group Advanced Energy United, argued that the justifications cited in the veto statements fail to adequately consider the value the state’s increasingly large numbers of rooftop solar systems, backup batteries, EVs, and smart appliances can deliver to the grid.

An August report from think tank GridLab and grid-data analytics startup Kevala found that California could cut energy costs for consumers by between $3.7 billion and $13.7 billion in 2030 by triggering home batteries, EV chargers, and smart thermostats to reduce summertime grid demand peaks that drive an outsize portion of utility grid costs.

The Brattle Group, a well-regarded energy consultancy, found in a 2024 analysis that VPPs could provide more than 15% of the state’s peak grid demand by 2035, delivering $550 million in annual utility customer savings. Simply put, paying homes and businesses for the grid value of devices they’ve already bought and installed is cheaper than the alternative of utilities building out new poles and wires and substations to serve peak demand.

“These distributed energy resources are already deployed, connected to customers, and connected to the internet,” Perez said. “The longer we wait to tap into this potential, the longer we waste away the savings.”

To date, the VPP programs run by California’s major utilities have failed to capture that savings value. In fact, the programs administered by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) have seen their overall capacity fall over the past five years or so, even as installations of the underlying technologies have risen.

The saving grace for VPPs in California has been the Demand Side Grid Support program, which is administered by the California Energy Commission (CEC) and has expanded rapidly in the past three years. A Brattle Group study released in August found that the roughly 700 megawatts of capacity from solar-charged batteries in homes and businesses enrolled in the DSGS program could save California utility customers from $28 million to $206 million over the next four years.

But last month the DSGS program was stripped of its funding during last-minute negotiations between legislative leaders and Newsom’s staff, leaving its future in doubt.

That’s frustrating to companies like Sunrun, the leading U.S. residential solar and battery installer, which has enlisted customers in California to supply hundreds of megawatts of DSGS capacity from their solar-charged batteries.

“Do we want to leverage existing infrastructure — electrons in batteries that are already there — and non-ratepayer capital to lower rates for everyone in creating a more efficient and smarter grid?” said Walker Wright, Sunrun’s vice president of public policy. “Yes or no?”

Because of changes made during closed-door negotiations in August, the VPP legislation vetoed by Newsom was relatively limited, but it still would have made a positive difference had it passed, said Gabriela Olmedo, regulatory affairs specialist at EnergyHub, a company that manages demand-side resources and virtual power plants in the U.S. and Canada.

“These were unopposed bills that were pretty uncontroversial but would have made impactful steps toward enhancing load flexibility in California,” she said. “We can’t afford to keep leaving these readily available and affordable solutions off the table.”

SB 541, for instance, would have authorized the CEC to create regulations to track the progress toward a state-mandated goal of achieving 7 gigawatts of “load shift” capacity by 2030 across utilities, community energy providers, and other entities supplying power to customers. Newsom’s veto statement said the bill would have been “disruptive of existing and planned efforts” by the CPUC, CEC, and state grid operator CAISO.

“I’m disappointed in this veto,” state Senator Josh Becker, the Democrat who authored SB 541, said in a statement to Canary Media. “This bill was about affordability,” he said. “Next year this area will be a focus of the clean energy community. Clearly we have some educating to do.”

AB 44 would have authorized the CEC to expand a method it has used to help some of California’s community choice aggregators (CCAs) tap VPPs to reduce peak demand.

Newsom’s veto statement declared that the bill “does not align” with the long-running effort by the CPUC to reform the Resource Adequacy program that sets the rules for how these grid needs are met. But critics say the CPUC has consistently failed to allow VPPs and other distributed energy resources to offset the increasingly high prices that utilities and CCAs are bearing to meet those needs.

AB 740 would have instructed the CEC to work with the CPUC, CAISO, and an advisory group representing disadvantaged communities to adopt a VPP deployment plan by November 2026.

Newsom’s veto statement declared that the bill would result in “costs to the CEC’s primary operating fund, which is currently facing an ongoing structural deficit.” But critics have pointed out that the text of the law would have instructed the VPP plan only to move forward “subject to available funding,” which would have forestalled any budget impacts.

“Even if it were signed, it would not have to be implemented unless the state budget proactively funded it,” Perez said. “It is very disappointing that we can’t even have the agencies talk about this in a comprehensive way. It’s kind of shocking that even that’s not allowed.”

California has labored for years to build enough clean energy to wean itself off fossil fuels. Now the effort is paying off in an undeniable way.

President Donald Trump’s Department of Energy might tweet that solar plants are “essentially worthless when it is dark outside.” But in California, batteries are proving the opposite, by shifting ever more solar into evening and nighttime hours. Consequently, solar generation hit new highs in the first half of the year, and fossil-gas generation has fallen rapidly in turn.

From January to July, as noted by Reuters, solar generation delivered 39% of the state’s generation, a record level, while fossil fuels provided just 26%, a new low since the dawn of modern gas power. In April, a temperate shoulder month, gas generated less than 20%. For context, across all of last year, solar provided 32% of California’s power — the highest rate of any U.S. state — nearly unseating gas as the largest source of power.

These trends have resulted in numerous clean energy records this summer. In the California Independent System Operator’s grid, which serves most of the state, solar delivered a record 21.7 gigawatts just past noon on July 30. Two days later, at 7:30 p.m., the battery fleet set its own record, nearing 11 gigawatts of instantaneous discharge for the very first time (it has since beat that record).

California’s electricity supply increasingly diverges from the nation’s. Gas has predominated since 2016, and now accounts for more than 40% of U.S. generation; coal, meanwhile, has fallen to around 16%. The carbon-free cohort includes nuclear and renewables at around 20% each. Solar, including rooftop systems, provided about 7% of U.S. electricity last year, according to Ember.

Initially, California’s billions of dollars in solar subsidies and suite of supporting policies couldn’t overcome the state’s gas dependency. The solar systems cranked out excess power through the sunny hours, much of which got curtailed for lack of simultaneous demand, then California turned to fossil fuels to keep the lights on at night. That addiction at times overpowered the state’s environmental ethos: California even opted in 2020 to waive enforcement of a regulation protecting marine life because it would have shuttered a number of coastal gas plants that the grid wasn’t ready to lose, despite having a decade to prepare for the rule.

Such desperation gave temporary succor to solar skeptics and gas boosters. But when an energy system starts to change, snapshots in time are less instructive than the trend lines. And California’s trend lines have been pointing in one direction.

While the state hasn’t been building new gas generation, it has connected gigawatts of new solar and batteries each year. These resources are nearly free to operate once built, while gas plant owners have to buy fuel to combust and keep complex machinery in fine working order. And the price of gas has been going up, amid greater demand both at home (due to data center expansion) and abroad (with liquefied exports going to the highest bidder). Now California’s gas plants have more competition in the peak hours from cheaper, cleaner resources; they’re getting squeezed toward fewer hours of intense demand.

But it would be a mistake to think that these trends stop at the Sierra Nevada. Indeed, these patterns are playing out nationally: Very little new gas capacity is getting built, quite a lot of solar and batteries are, and gas prices are going up.

Some regions allow developers to respond nimbly to these trends, namely Texas, which indeed has leapt ahead of California in its pace of solar and storage installations. Other regions obstruct such dynamism and face the consequences, like the mid-Atlantic wholesale markets run by PJM, where skyrocketing capacity auctions are pushing costs to crisis levels.

California’s grid overhaul has been a long time coming, and one lesson here is that big changes — like redesigning the energy system for the world’s fourth largest economy — take time. But other states won’t have to wait as long: They can tap into a mature supply chain that scaled up thanks to California and other early adopters, plus the industrial expertise to design and manage large solar construction efforts and the financing options de-risked by years of data from earlier projects.

The federal government is trying to stymie renewables however it can. But California is demonstrating the rewards for getting solar to escape velocity, and that momentum is set to carry forward in the coming years.

America’s fledgling carbon-removal industry is on edge following funding cuts from the Trump administration — and rumors of even further clawbacks to follow.

On Tuesday, a list of potential U.S. Department of Energy award terminations shared with Canary Media, and which circulated in Washington, included two giant direct-air-capture (DAC) hubs planned in Louisiana and Texas. Each project has received about $50 million to begin planning and developing CO2-sucking facilities, and together they are slated to receive up to $1.1 billion in federal support.

However, a spokesperson for DOE said that it is “incorrect to suggest those two projects have been terminated” and that no determinations have been made beyond the award cancellations announced last week. On Oct. 2, the agency said it was scrapping 321 grants totaling over $7.5 billion — including nearly $50 million to help 10 smaller DAC initiatives begin concept and engineering studies for future installations.

“The Department continues to conduct an individualized and thorough review of financial awards made by the previous administration,” DOE press secretary Ben Dietderich said in an email to Canary Media. Following last week’s cancellations, Energy Secretary Chris Wright said more cuts would be announced, though he did not specify further.

The real and rumored grant terminations reflect the chaos and confusion that’s engulfed virtually every federally backed energy project since the start of the second Trump administration. Even developers whose awards haven’t been slashed — at least not yet — must try to navigate the lengthy and complicated funding process with an agency wracked by layoffs.

For carbon removal in particular, “a lot of these projects have kind of been in limbo this year, not sure of if they should commence and continue their work,” said Courtni Holness, the managing policy adviser for the nonprofit Carbon180. “There’s a lot of uncertainty around if they’re going to get continued funding, if they’ll be able to be reimbursed.”

While cutting greenhouse gas emissions is the most urgent and necessary way to tackle climate change, the world will also need to remove CO2 from the atmosphere in order to avert the worst consequences of a warming planet, climate scientists say. However, most carbon-removal solutions are early-stage, expensive, and largely unproven at any meaningful scale, making government support critical to their success.

The Biden administration launched the Regional Direct Air Capture Hubs program in 2023 with $3.5 billion in funding provided by the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law. The DAC initiative was part of a broader push by the DOE to help the private sector deploy novel technologies at commercial scale.

Funding for the Louisiana and Texas megaprojects “represented the largest ever public investment in carbon removal,” said Erin Burns, executive director of Carbon180. If completed as planned, the hubs are each expected to create thousands of jobs in the regions where they’ll operate.

The South Texas DAC Hub is an initiative of the Occidental Petroleum subsidiary 1PointFive. The project is located just south of Corpus Christi and is expected to be capable of removing over 1 million metric tons of CO2 per year — roughly equal to the annual emissions from 2.5 gas-fired power plants. The project will use technology developed by Carbon Engineering, a company that 1PointFive acquired for $1.1 billion in November 2023.

DAC plants can use giant industrial fans to draw in large amounts of air, then separate out the carbon using chemical solutions or filtered materials. The captured CO2 can be injected into deep geological formations, or it can be repurposed to make valuable industrial products, such as concrete and synthetic fuels.

1PointFive didn’t immediately return Canary’s request for comment on the purported DOE funding cuts.

The company is separately building another DAC facility in the Texas Permian Basin that is designed to capture up to 500,000 metric tons of CO2 annually and could begin operating later this year. That project, called Stratos, will likely use captured carbon for “enhanced oil recovery,” a process that involves pumping the gas into older oil wells to force up any remaining fossil fuels.

Although Stratos didn’t receive a DOE grant, the operation will still likely benefit from the federal 45Q tax credit, which was expanded under the GOP budget law that passed in July — mainly for the benefit of carbon-capturing projects linked to oil production.

Meanwhile, in Louisiana, a coalition of companies is building a DAC hub called Project Cypress. Climeworks and Heirloom, two leading carbon-removal developers, are partnering with the applied-sciences organization Battelle to design and operate two facilities, which together are intended to capture over 1 million metric tons of carbon per year. The company Gulf Coast Sequestration will then take the captured CO2 and permanently store it in a deep saline aquifer.

Climeworks, a Swiss company, will use its fan-driven technology, a version of which is already operating in Iceland. The U.S. startup Heirloom will build a separate plant for its own DAC process, which involves heating trays of limestone inside kilns to turn the mineral into a “sponge” that absorbs CO2 from the atmosphere.

Vikrum Aiyer, Heirloom’s head of global policy, said on Tuesday that the company wasn’t “aware of a decision from DOE” to cancel its federal award and that the companies continue “to productively engage with the administration in a project review.”

Both the South Texas and Louisiana DAC hubs still face significant hurdles to crossing the finish line — including sourcing massive amounts of clean electricity to run their machines — even if they ultimately receive federal funding as promised. 1PointFive, for example, has run into local opposition, in part because of its association with the fossil fuel industry. Community advocates in both states have said they felt shut out of early planning processes that should have included them.

For DAC proponents, rescinding federal awards means the U.S. could risk losing out on the potential jobs and investment these first-of-a-kind projects are expected to create, especially as other countries press ahead. China, for example, has announced plans to build 37 domestic “carbon management and removal” projects by 2030, according to the Carbon Removal Alliance.

“Carbon removal is essential to meeting our climate targets and fueling energy security — that’s why it’s the world’s next trillion-dollar industry,” Carbon Removal Alliance and another advocacy group, the Carbon Business Council, said in a joint statement.

The future of community solar is dimming, hampered by federal attacks on clean energy and shifts in state markets.

Installations of the shared-solar approach took a nosedive in the first half of 2025, dropping by 36% from the same period last year, according to a new report by consultancy Wood Mackenzie.

Working in collaboration with the Coalition for Community Solar Access, an industry trade group, Wood Mackenzie forecasts that by the end of 2025, installations will fall by 29% from 2024’s record high of 1.7 gigawatts. According to the analysis, growth will likely contract by an average of about 12% annually through 2030.

“I’m dismayed by this report,” said John Farrell, co-director of the research and advocacy nonprofit Institute for Local Self-Reliance. “Of the places where we have policies [that drive community solar], it looks like things are slowing down.”

Community solar makes clean power accessible to those who can’t put solar panels on their roofs — be it because they rent, can’t afford them, or have other reasons. Households can subscribe to a share of an off-site array, which is typically 2 to 20 megawatts, per the report, to get credit for the power and save on their energy bills. Third-party developers usually build and own these installations — not utilities.

About 9.1 gigawatts of shared solar have been installed in the U.S. to date, according to the report’s authors. They expect community solar capacity to reach roughly 16 GW by 2030.

The megabill that Republicans passed in July is a major reason for the community solar market’s shake-up. The law set an early expiration date for a key tax credit worth 30% to 50% of the cost of a project. Developers once had until 2034 to claim it; now companies must either start construction by July 2026 and finish within four years or start producing power by the end of 2027.

Because of the law’s passage, Wood Mackenzie slashed its community solar figures through 2030 by about 8%, or 655 megawatts, from its prior forecast, said Caitlin Connelly, senior analyst at the firm and lead author of the report.

But factors at the state level are also contributing to the slowdown. In particular, New York and Maine are driving the steep decline.

Developers in New York, a mature market, are having trouble finding sites, paying higher permitting and land costs, and having to wait an average of nearly three years to get connected to the grid, making projects more expensive to develop, Connelly said.

Meanwhile, in Maine, two regulatory changes are at play. Last year saw record growth as developers sprinted to get projects done by the December phaseout of the state’s net metering program, leading to fewer in the pipeline now, Connelly noted. In June, legislators also passed a bill that retroactively overhauled compensation for community solar power and added fees for new and established projects. The industry has said these provisions will make the state a “pariah for investors.”

Some states, such as Virginia and New Mexico, also have caps on the size of their community solar programs that are limiting new developments, according to Connelly.

And more federal turbulence could be ahead.

The Trump administration is also trying to claw back funding that would’ve supported solar: the $7 billion Solar for All program and the $20 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, programs passed under the landmark Inflation Reduction Act.

“The impact of [losing] Solar for All is one that we are tracking closely,” Connelly said, as the move could stymie community solar in places where it’s just getting off the ground.

While this year is likely to be a rough one for community solar, Connelly sees growth returning in 2026 and 2027. This is in part due to rebounds in Massachusetts and New Jersey, both of which are transitioning into new iterations of existing programs.

Massachusetts will open up its Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target program, SMART 3.0, to developers on October 15. And New Jersey recently eliminated a 150-megawatt annual cap and unlocked a whopping 3 gigawatts of community solar capacity.

But that growth is just a temporary reprieve. Over the longer term, the forecast shows community solar installations trending down.

A few factors could change the sector’s fortunes, however.

For one, if states were to start new community solar programs, as well as address interconnection bottlenecks, they could drive up to 1.3 gigawatts of additional capacity through 2030, according to the report. But “we don’t really see any new programs opening up, at least in the near term,” Connelly said. “Policymakers have made a lot of progress in some state markets over the last six months to a year, but the difficulty is getting that legislation over the finish line.”

In deep red Montana, for example, legislators approved a new community solar program, with 100 in favor and 50 opposed, underscoring the model’s growing appeal to Republicans. But Gov. Greg Gianforte (R) vetoed the bill, claiming that it could result in “unreasonable costs” being foisted on other energy customers.

Only 24 states plus Washington, D.C., have passed community solar legislation as of February, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio, and Iowa are all considering shared-solar bills, said Jeff Cramer, president and CEO of the Coalition for Community Solar Access.

Other states could be tempted to authorize a flood of clean, cheap solar power. The grid is facing soaring demand from data centers, electric vehicles, buildings, and manufacturing, and distributed community solar is among the fastest options to deploy.

“If you want to build a new gas plant right now, you’re going to need five-plus years minimum to do it. You want to build a new utility-scale [solar or wind] facility — at least five years as well, and that’s pending the development of new transmission,” Cramer said.

By contrast, community solar has a typical development timeline of six months to two years, he added. “The only kind of capacity that we can build close to load and faster than those timelines to meet load growth and grid congestion is distributed solar.”

Even as the federal government attempts to prop up the waning coal industry, New England’s last coal-fired power plant has ceased operations three years ahead of its planned retirement date. The closure of the New Hampshire facility paves the way for its owner to press ahead with an initiative to transform the site into a clean energy complex including solar panels and battery storage systems.

“The end of coal is real, and it is here,” said Catherine Corkery, chapter director for Sierra Club New Hampshire. “We’re really excited about the next chapter.”

News of the closure came on the same day the Trump administration announced plans to resuscitate the coal sector by opening millions of acres of federal land to mining operations and investing $625 million in life-extending upgrades for coal plants. The administration had already released a blueprint for rolling back coal-related environmental regulations.

The announcement was the latest offensive in the administration’s pro-coal agenda. The federal government has twice extended the scheduled closure date of the coal-burning J.H. Campbell plant in Michigan, and U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright has declared it a mission of the administration to keep coal plants open, saying the facilities are needed to ensure grid reliability and lower prices.

However, the closure in New Hampshire — so far undisputed by the federal government — demonstrates that prolonging operations at some facilities just doesn’t make economic sense for their owners.

“Coal has been incredibly challenged in the New England market for over a decade,” said Dan Dolan, president of the New England Power Generators Association.

Merrimack Station, a 438-megawatt power plant, came online in the 1960s and provided baseload power to the New England region for decades. Gradually, though, natural gas — which is cheaper and more efficient — took over the regional market. In 2000, gas-fired plants generated less than 15% of the region’s electricity; last year, they produced more than half.

Additionally, solar power production accelerated from 2010 on, lowering demand on the grid during the day and creating more evening peaks. Coal plants take longer to ramp up production than other sources, and are therefore less economical for these shorter bursts of demand, Dolan said.

In recent years, Merrimack operated only a few weeks annually. In 2024, the plant generated just 0.22% of the region’s electricity. It wasn’t making enough money to justify continued operations, observers said.

The closure “is emblematic of the transition that has been occurring in the generation fleet in New England for many years,” Dolan said. “The combination of all those factors has meant that coal facilities are no longer economic in this market.”

Granite Shore Power, the plant’s owner, first announced its intention to shutter Merrimack in March 2024, following years of protests and legal wrangling by environmental advocates. The company pledged to cease coal-fired operations by 2028 to settle a lawsuit claiming that the facility was in violation of the federal Clean Water Act. The agreement included another commitment to shut down the company’s Schiller plant in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, by the end of 2025; this smaller plant can burn coal but hasn’t done so since 2020.

At the time, the company outlined a proposal to repurpose the 400-acre Merrimack site, just outside Concord, for clean energy projects, taking advantage of existing electric infrastructure to connect a 120-megawatt combined solar and battery storage system to the grid.

It is not yet clear whether changes in federal renewable energy policies will affect this vision. In a statement announcing the Merrimack closure, Granite Shore Power was less specific about its plans than it had been, saying, “We continue to consider all opportunities for redevelopment” of the site, but declining to follow up with more detail.

Still, advocates are looking ahead with optimism.

“This is progress — there’s no doubt the math is there,” Corkery said. “It is never over until it is over, but I am very hopeful.”

London, 7 October 2025 – Solar and wind outpaced the growth in global electricity demand in the first half of 2025, resulting in a very small decline in both coal and gas, compared to the same period last year. New analysis from Ember shows that record solar growth and steady wind expansion are reshaping the global power mix, as renewables overtake coal for the first time on record.

“We are seeing the first signs of a crucial turning point,” said Małgorzata Wiatros-Motyka, Senior Electricity Analyst at Ember. “Solar and wind are now growing fast enough to meet the world’s growing appetite for electricity. This marks the beginning of a shift where clean power is keeping pace with demand growth.”

Global electricity demand rose 2.6% in the first half of 2025, adding 369 TWh compared to the same period last year. Solar alone met 83% of the rise, thanks to record generation growth in absolute terms (306 TWh, +31% year-on-year).

Solar and wind grew quickly enough to meet rising demand and start to replace fossil generation. Coal fell by 0.6% (-31 TWh) and gas by 0.2% (-6 TWh), only partly offset by a small rise in other fossil generation, for a total decline of 0.3% (-27 TWh). As a result, global power sector emissions fell by 0.2%.

For the first time ever on record, renewables generated more power than coal. Renewables supplied 5,072 TWh of global electricity, up from 4,709 TWh in the same period in 2024, overtaking coal at 4,896 TWh, down 31 TWh year-on-year.

The 0.3% (-27 TWh) drop in fossil fuel generation was modest but significant, indicating that wind and solar generation are growing quickly enough that in some circumstances they can now meet total demand growth. As their exponential rise continues, they are likely to outstrip demand growth for longer and longer periods, cementing the decline of fossil generation.

The world’s four largest economies – China, India, the EU and the US – continued to shape the global outcome.

China and India both saw fossil generation fall in the first half of 2025 as clean power growth outpaced demand. China remained the leader in clean energy growth, adding more solar and wind than the rest of the world combined, helping to cut China’s fossil generation by 2% (-58.7 TWh) in the first half of 2025.

In the same period in India, growth in clean sources was more than three times bigger than demand growth. However, demand was exceptionally low at 1.3% (+12 TWh), compared to the same period last year at 9% (+75 TWh).

India’s record solar and wind expansion, combined with lower demand, drove down fossil fuels in the country, with coal falling 3.1% (-22 TWh) and gas 34% (-7.1 TWh).

By contrast, fossil generation rose in the US and the EU. In the US, demand growth outpaced clean power, driving up fossil generation. In the EU, weaker wind and hydro output led to higher gas and coal generation.

With half the world already past the peak of fossil generation, Ember finds clean power can keep pace with rising electricity demand, but progress is uneven. In most economies, faster deployment of solar, wind and batteries could bring benefits.

This analysis confirms what we are witnessing on the ground: solar and wind are no longer marginal technologies—they are driving the global power system forward. The fact that renewables have overtaken coal for the first time marks a historic shift. But to lock in this progress, governments and industry must accelerate investment in solar, wind, and battery storage, ensuring that clean, affordable, and reliable electricity reaches communities everywhere.

-- Sonia Dunlop

CEO, Global Solar Council

We are seeing the first signs of a crucial turning point. Solar and wind are now growing fast enough to meet the world’s growing appetite for electricity. This marks the beginning of a shift where clean power is keeping pace with demand growth. As costs of technologies continue to fall, now is the perfect moment to embrace the economic, social and health benefits that come with increased solar, wind and batteries. As costs of technologies continue to fall, now is the perfect moment to embrace the economic, social and health benefits that come with increased solar, wind and batteries.

-- Malgorzata Wiatros-Motyka

Senior Electricity Analyst, Ember

One of the largest ports in the Midwest is officially starting to decarbonize, thanks to a Biden-era grant program that has so far survived the Trump administration’s assault on all things clean energy.

Late last month, the Port of Cleveland began renovating its main warehouse on the shore of Lake Erie. When the work is complete, Warehouse A will have roughly 2 megawatts’ worth of rooftop solar panels, plus battery storage and numerous charging ports for cargo-handling equipment.

Cleveland, which received a $94 million award from the Clean Ports Program announced by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency last fall, is one of three Great Lakes port groups benefitting from the funding. Although the agency has reneged on many other funding commitments under President Donald Trump, work and payments for the $2.9 billion ports program are still moving ahead.

The country’s more than 300 ports, which ship and receive the materials, food, and other products that Americans rely on, are mostly powered by fossil fuels. Their cranes, forklifts, and other freight-handling equipment burn diesel fuel, and so do the ships and boats docked at those ports, sending not only planet-warming greenhouse gases into the atmosphere but toxic pollution that can harm the people who work and live nearby.

To address both problems, the Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port Authority has set a goal of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. “We want to have a lower impact on surrounding communities. We also want to stay ahead of regulations,” said Bryan Celik, a contract engineer for the Port of Cleveland. The goal covers the port’s direct Scope 1 emissions, as well as its Scope 2 emissions for energy use.

Global shipping companies face increasing pressure to decarbonize boats and ships, and technology for wind-powered and battery-powered vessels has improved in recent years.

The U.S. has previously taken steps toward decarbonizing shipping, including by partnering with Norway on the Green Shipping Challenge, but the Trump administration has scuttled progress this year. Trump also opposes a proposed global fee on greenhouse gas emissions that the International Maritime Organization will consider formally adopting this month.

The nearly $3 billion in Clean Ports Program funding nationwide “has transformative potential for U.S. ports,” said Jerold Brito, a program associate with the Electrification Coalition, a nonprofit that helped coordinate a Sept. 25 event on regional port electrification hosted by the Port of Cleveland.

Indeed, Cleveland is not alone in its efforts to clean up its port. The Detroit/Wayne County Port Authority, for example, has an even more ambitious goal of reaching net-zero for its Scope 1 and 2 emissions by 2040, said its sustainability manager, Taylor Mitchell.

Because so much is shipped through ports, Mitchell says, electrifying these hubs of commerce is a “cool opportunity to have a really huge impact on the planet.”

During the late September event organized by the Electrification Coalition, representatives from Cleveland, Detroit, and Hamilton, Ontario, met with contractors and others in industry and nonprofit organizations to share plans and address challenges.

For Brito, this sort of collaboration is key to the success of port electrification.

“Realizing that potential will require buy-in from — and coordination with — the regional networks of industry, nonprofit, and government actors affected by ports’ electrification,” he said.

For example, work at Cleveland’s Warehouse A necessitates collaborating with Cleveland Public Power, the city’s municipal utility. While solar panels and battery storage at the warehouse will eventually provide much of the port’s electricity needs, it still requires more grid power in order to fully electrify.

Other phases of the work will add cabling and connections for vessels to operate with electric power while they’re in port. That “shore power,” or cold ironing, could let boats and ships shut off their diesel engines until it’s time to get underway again.

Additionally, Logistec USA, the port operator, will acquire an electric crane and electric forklifts. And the Great Lakes Towing Co. will build two electric tugboats.

Coordination with other stakeholders also presents challenges for the Detroit/Wayne County Port Authority. “We really don’t have much of a footprint ourselves,” except for a cruise dock, noted Mark Schrupp, executive director for the port authority.

Instead, most cargo carried by boats and ships moves through private docks in industrial port areas around the city. “We’ve definitely got to think of ways to get the private sector on board.”

But companies may not want to take some steps on an individual basis, such as constructing and installing power lines and charging equipment at privately owned docks that would only be used part-time.

So the Detroit/Wayne County Port Authority is exploring alternatives, such as how hydrogen could produce clean electricity aboard a boat that could then act as a mobile plug-in port for docked vessels’ shore power.

Developing shore power calls for even more groups working together on a broader scale. “We really need a standard as much for a port as for a ship, because if there is a mismatch, you would have invested all of that for nothing,” said Hugo Daniel, a doctoral candidate at the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec who researches engineering challenges in shore power. Ideally, Canada and the United States will join forces on a strategy for the Great Lakes that aligns with practices from California, the European Union, and China, he said.

Without standards set at the regional and national level, states and cities that try to compel changes on their own could see shippers simply move to other ports with more lax rules, Schrupp said. While some firms looking to slash their supply-chain emissions might prefer to work with a port that is decarbonizing operations, others might avoid areas that could restrict their diesel use.

Great Lakes ports are big economic drivers. More than 23,000 jobs and about $7 billion in annual economic activity are tied to Cleveland’s port alone, Celik said. Yet it and other inland ports handle a smaller volume of business than most of their counterparts on the East and West coasts, making it that much harder to spread costs and recoup major investments like electrification.

“Like all previous transitions, the electrification transition will present novel challenges and opportunities,” Brito said. “So Great Lakes ports must remain nimble.”