The article was originally published by Earthobservatory.nasa.gov

August 21, 2025

September 6, 2025

Ice covers about 1.7 million square kilometers (656,000 square miles) of Greenland, forming the largest ice sheet on Earth outside of Antarctica. Each summer, its surface begins to melt under the warmth of the Sun, intensified by the season’s long daylight hours and sometimes further enhanced by clouds and rain.

Greenland’s melting season usually runs from May to early September. The 2025 season was considered “moderately intense,” ranking 19th in the 47-year satellite record for cumulative daily melt area as of late August, according to an analysis by the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC). This year’s season featured an extended period of melting in part of July and a sharp increase in warmth and melting in mid-August.

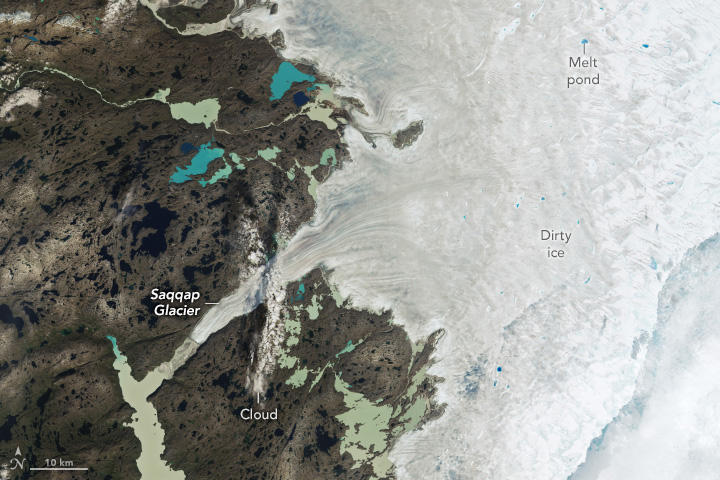

The mid-August spike, which was preceded by significant rainfall in some areas, peaked on August 21, when melting was observed across nearly 35 percent of the ice sheet—a record for that date, according to the NSIDC. These satellite images show the ice sheet on that day (left) and nearly two weeks later (right), along part of its southwestern edge about 150 kilometers (90 miles) northeast of the capital city of Nuuk (not shown). Both images were captured by the OLI-2 (Operational Land Imager-2) on Landsat 9.

In the August image, a vast expanse of gray, “dirty” ice is visible. The darker appearance is due to particles like black carbon and dust that have accumulated on the ice sheet. As the snow and ice melt, these impurities are left behind, making the ice appear even darker. This darkening reduces the ice’s albedo—its ability to reflect sunlight—causing it to absorb more solar energy and melt even faster during the summer months. Several ponds of light- and deep-blue meltwater dot the ice, and scattered clouds cover part of the ice sheet in the middle and bottom-right of the scene.

By the date of the September image, a fresh layer of snow appears to cover much of the dirty ice as well as some of the land. While major melt events have occurred as late as September in previous years, they become less likely this time of year as temperatures typically drop with the Arctic’s diminishing daylight.

Scientists track seasonal melting each year because it is one of the ways the massive Greenland Ice Sheet loses ice. (Iceberg calving and melting at the base of tidewater glaciers also play a role.) As air and water temperatures have risen in recent decades, ice losses have outpaced ice gains, contributing to sea level rise.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Kathryn Hansen.