Correction: More than 11,000 natural gas storage wells across the U.S. may have a single barrier of failure that puts them at risk of a major methane leak. An item in yesterday’s digest mischaracterized their risk.

UTILITIES: The largest U.S. utilities have offered uneven support and sometimes conflicting positions while lobbying on climate policy in recent years, according to a nonprofit group’s new report. (Utility Dive)

ELECTRIC VEHICLES:

STORAGE: Global venture capital investment in energy storage soared to new records last year, with 86 deals totalling $9.2 billion in funding. (Utility Dive)

HYDROGEN:

EMISSIONS: The U.S. Energy Department allocates $254 million for projects to cut industrial greenhouse gas emissions. (Utility Dive)

GRID:

MINING: The mining industry aims for a rebrand as it becomes a necessary piece of the clean energy transition and looks to recruit young, climate-conscious employees. (Grist)

NUCLEAR: The Biden administration is reportedly preparing to offer a conditional $1.5 billion loan to reopen a shuttered nuclear plant in southwestern Michigan. (Reuters)

CLIMATE:

On a November afternoon in 2022, a 57-year-old well tapped into an underground natural gas storage reservoir in western Pennsylvania started leaking, fast enough that people a few miles away heard a loud, jet engine-like noise.

By the time the leak was stopped nearly two weeks later, roughly 16,000 metric tons of methane had escaped into the atmosphere, the equivalent of more than the annual greenhouse gas emissions from 300,000 gas-powered cars.

The blowout of a well at the Rager Mountain gas storage field was the worst methane leak from underground storage since Aliso Canyon in California in 2015. That incident forced thousands of people from their homes and sickened many of them, taking four months to contain. In 2021, 35,000 plaintiffs in one class-action lawsuit were awarded up to $1.5 billion in damages.

While not as large or imminently dangerous to residents, the Rager Mountain leak was a “disaster,” according to one Pennsylvania regulator. Bloomberg labeled it the United States’ worst climate disaster that year.

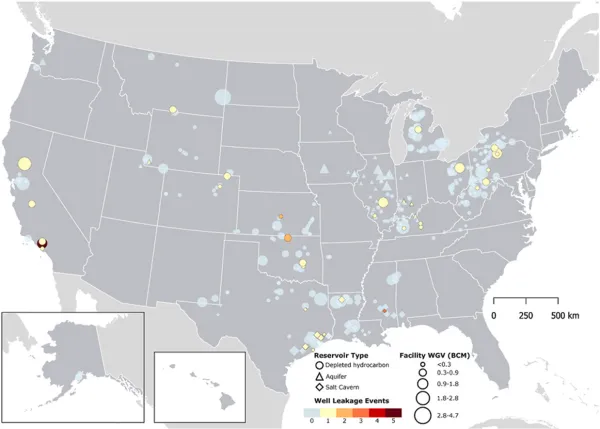

The natural gas that leaked methane in Pennsylvania and California is not stored in tanks but in giant underground geological formations accessed by multiple wells. There are about 400 such storage fields across 32 states.

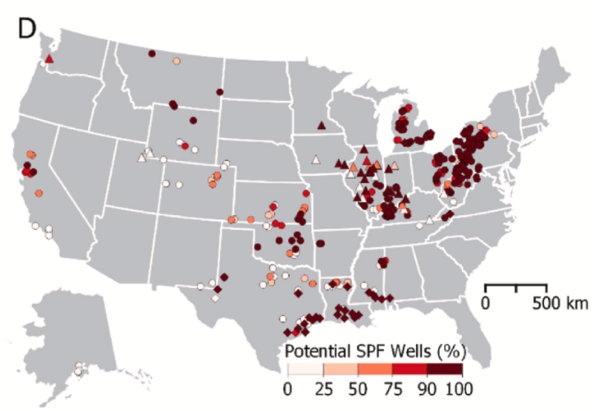

According to a new report, there are thousands more potential opportunities for a similar situation across the country. The new analysis of data collected by federal regulators suggests there are as many as 11,446 storage wells in the country with the same key risk as the wells that failed at Rager Mountain and Aliso Canyon: They have only a single barrier to failure.

“That population is a lot larger than we had estimated, or other researchers had estimated with state [data],” says Greg Lackey, an author on the study and researcher at the Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory.

All but one of Pennsylvania’s 49 gas storage fields has at least one potential single point of failure well, researchers found.

Natural gas is primarily made up of methane, a greenhouse gas 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide in the short-term. Methane leaks from oil and gas infrastructure are under increasing scrutiny in the United States and worldwide, as stopping them represents a relatively cheap and effective way to prevent greenhouse gas emissions, the primary cause of global warming.

Leaks from gas storage are only one part of the industry’s methane problem. Such facilities also are at risk of dramatic blowouts that are hard to control because they are connected to large, pressurized reservoirs of gas.

Regulations put in place on gas storage post-Aliso Canyon are still rolling out, including a requirement for baseline risk assessments on all wells by 2027. New EPA rules on methane leaks and repair and a planned federal fee on “waste” methane would impact gas storage as well.

The fee, which is still being finalized, would force companies to eventually pay up to $1,500 per metric ton of methane in excess of the equivalent of 25,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide, a threshold the Rager Mountain leak meets almost 20 times over. Industry groups have pushed back against the fee, arguing it would harm smaller oil and gas companies and discourage oil and gas production overall.

Many of these wells are decades-old and not originally designed for storage. They have gone through the stresses of repeated cycles of injecting and withdrawing gas. Some, like Rager Mountain, are in relatively rural, sparsely-populated areas, but others are close to neighborhoods in Pennsylvania, Ohio and California.

The Rager Mountain leak was caused by a break below ground in one well’s casing — the barrier between where pressurized gas flows and the geology around it. The well had become heavily corroded from exposure to water, air and organic matter through an open valve, according to an third-party analysis submitted to regulators and obtained through a public records request.

“They probably didn’t realize it, but they were creating an optimum case for corrosion,” says Dan Arthur, president of the engineering and technical services firm ALL Consulting, who reviewed the analysis.

Arthur says older wells in storage fields haven’t been given “as much significance” as they should be, and operators need to make sure they’re fully addressing well integrity.

“Age is a risk factor that you have to consider, but it also depends on how you are caring for the well,” he says. Redundant barriers reduce the risk of methane escaping if the well casing fails, Arthur and Lackey say.

Minimum federal safety standards on underground storage fields were set less than a decade ago in the aftermath of the Aliso Canyon leak. One of the federal agencies in charge of regulating gas storage sites, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, only began collecting regular data on underground storage fields in 2017.

The number of wells with potentially only one barrier was three times larger than previously estimated before the PHMSA data became available, Lackey says. This “single point of failure” design featured in both Rager Mountain and Aliso Canyon blowouts is present in as many as 64% of all gas storage wells in the United States, his research found.

But the data reported to PHMSA is not enough to confirm how many of these wells actually have a single point of failure that would flag wells at the highest risk of another blowout, Lackey says. Researchers would need more information about each well’s design and construction, he says.

“What you don’t get insight into is how many other casings there are, or where the locations of cement are,” Lackey says, describing additional barriers that would lower the risk.

Rager Mountain’s owner and operator, Equitrans, had its own risk ranking of storage wells, according to the third-party analysis. While Rager is the company’s largest field in Pennsylvania, its wells were not the highest ranked in the company’s own risk management plan; Others were higher up the list because of their proximity to residential areas.

Both Peoples Natural Gas, the previous owner of the field, and Equitrans “recognized that corrosion was an issue,” so the companies used probes, known as “logs,” to examine the integrity of the well casings. But, the analysis noted, “Such a strategy is dependent on the logging being reasonably accurate.”

A 2016 test of the casing wall of the well that eventually failed underestimated its corrosion, the report says. When Equitrans reran the test after the blowout using an updated algorithm, it showed far more corrosion.

In the wake of the Rager Mountain blowout, Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection, said it was considering a “top to bottom review” of the state’s gas storage industry. Pennsylvania is one of a handful of states that have their own regulations covering gas storage.

“Everything is on the table for consideration in terms of making sure this industry is regulated appropriately and the public is protected and the environment is protected from potential incidents like this happening again,” said Kurt Klapkowski, acting deputy secretary for DEP’s Oil and Gas Management office, a month after the incident.

But after a successful effort by Equitrans to move the bulk of the incident investigation to federal regulators, DEP appears uncertain or unable to move forward with such a review. Klapkowski told the agency’s Oil and Gas board in September that regulators were “trying to figure out where our jurisdiction ends or might be preempted by the federal government.”

Pennsylvania DEP’s investigation into surface and groundwater contamination at Rager Mountain is ongoing, the agency said in an emailed statement, and it “remains committed to its goal of inspecting storage field wells on an annual basis regardless of risk.”

Wells are assessed through surface inspections and information reported by operators, DEP added, using multiple factors to prioritize wells for inspection, including the potential environmental impact and likelihood of failure, as well as proximity to population.

Equitrans has taken several steps to reduce risk in its storage fields, spokesperson Natalie Cox said in an emailed statement. They include reprocessing older well tests, running additional tests on another 100 wells in 2023, and changing its requirements for when to add protective gel to reduce corrosion. The company did not answer questions about whether these tests led to any well replacements.

Lackey’s study also found that nationally, while most leaks from gas storage were connected with accidents or well improvement projects known as workovers, leaks from corrosion released a much larger volume of methane.

“If it’s a valve or something that’s broken off on the wellhead, that might be easier to contain, rather than something downhole that would be exposed to higher pressures within the well,” he says. “During workovers you have systems in place to contain the well … whereas with corrosion, that’s something going on silently in the background.”

While a 2016 government task force recommended phasing out single point of failure of wells, ultimately the federal minimum standards only required operators to address them through submitting risk-management plans to federal regulators — plans that are not public.

The release of gas from Rager Mountain in November 2022 represented about 15% of the field’s working storage volume. Underground storage fields act as “a huge battery system,” says Drew Michanowicz, a researcher who has studied their proximity to residential areas.

Major leaks from storage not only release huge volumes of greenhouse gases but also reduce reliability in areas where natural gas dominates home heating and electricity production, Michanowicz says.

The federal leak investigation at Rager Mountain remains open at least until regulators review work on fixing three temporarily plugged wells in the field, likely in the spring. But Rager Mountain is otherwise operating. In October, with PHMSA’s approval, Equitrans began injecting gas into the field for the winter.

Floodlight is a non-profit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action. This story was produced with support from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Natural gas can have a huge climate impact before it even makes it to your furnace or stove.

While the fuel releases fewer carbon emissions than coal when it’s burned, it’s mostly made up of methane — a planet-warming gas that’s far more potent than carbon in the short term if it leaks from gas infrastructure. And at thousands of gas storage wells across the U.S., leaks are more likely than storage site owners may be accounting for. As many as 11,446 storage wells could have a single point of failure, meaning only one thing has to go wrong for a leak to start, Floodlight’s analysis of a new report finds.

Those potential disasters could look just like what happened at the Rager Mountain storage site in November 2022.

At the Pennsylvania site, a heavily corroded gas storage well broke below the ground, sending methane aboveground and into the air. The leak wasn’t stopped for two weeks, and by then, it had released the equivalent of the annual greenhouse gas emissions from 300,000 gas-powered cars. Bloomberg even labelled it the worst climate disaster of the year.

And there’s more than just a climate risk. Storage fields essentially work as “a huge battery system” that keeps fuel ready to use in power plants and home heating, researcher Drew Michanowicz told Floodlight. Leaks jeopardize that supply.

It all makes for a big challenge for federal and state regulators as they work to keep energy resources secure and cut down on a big source of methane emissions.

Read the whole story from Floodlight here.

🚢 Hitting pause on gas: The Biden administration pauses all approvals of new liquefied natural gas export facilities to further review their climate and other impacts, crediting “the calls of young people and frontline communities” for its decision. (E&E News)

🏭 Fossil fuel switch: States are dependent on hundreds of millions of dollars of annual fossil fuel revenues that pay for schools and roads, and they’ll need to find other funding sources as they transition to renewables. (Axios)

🌎 Devastating climate impacts: Researchers estimate climate change has killed at least 4 million people around the world since 2000, crediting increasingly extreme weather for excess deaths. (Grist)

🏫 Building solar resilience: FEMA will soon start putting solar panels on schools, hospitals and other public buildings when they’re rebuilt after disasters, with the hopes of boosting resilience in future extreme weather events. (New York Times)

💸 Going public: In the face of high electric rates and unreliable power, several communities around the country are pushing to replace investor-owned utilities with public, resident-owned power companies. (Grist)

💰 Pro-propane: A propane industry lobbying group has spent millions of dollars over the past two years to promote the fuel as a clean energy source, even though it’s a byproduct of oil and gas refining. (The Guardian/Heated)

☀️ Solar for everyone: A solar nonprofit matches socially conscious investors’ cash with lower-income homeowners to spread the benefits of clean energy in a Minneapolis neighborhood. (Energy News Network)

🚘 An EV charging solution: Advocates say making many Level 1 charging outlets available to renters in large buildings could do more to convince them to adopt electric vehicles than installing a few faster charging ports. (Grist)

Facing a massive projected increase in electricity demand, Duke Energy on Wednesday proposed what advocates called a “tripling down” of new gas plants and scuttling a 2030 deadline to significantly curb its carbon pollution.

An update of a proposal submitted last summer, the bid comes after the company warned in November that major new economic development projects would drive electricity sales “well above” its “historical experience.”

The amended plans show the company expects a 12% increase in demand by 2038, driven largely by more than two dozen economic development projects in both Carolinas that had made “commitments sufficient to justify inclusion” in the new load forecast.

To meet the increased demand in the near term while preparing for decarbonization mandates in the long term, Duke wants to build two more large, “hydrogen-capable” gas plants than it proposed in August. Some hydrogen fuel could theoretically be zero-emitting but is not yet commercially available, and critics call the technology speculative.

The company also proposes an additional smaller, single-cycle gas plant. In all, Duke recommends nearly 9 gigawatts of new gas before 2035, almost three times what it anticipated in its first blueprint to cut carbon pollution, approved at the end of 2022.

“This plan is tripling down on the coal-to-gas transition, saddling customers with risky investments in new polluting power plants and failing to deliver the clean energy future called for in state law,” said Will Scott, Southeast Climate & Clean Energy Director for the Environmental Defense Fund, in a prepared statement.

On the bright side for renewables, the company does recommend a smidge more solar and battery storage. And most significantly, it proposes 2.4 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2035 — about two-thirds the size of the Kitty Hawk Wind energy area, the project off the Outer Banks that’s furthest along in development.

“Obviously, this is fantastic news, that we’re seeing offshore wind in the Carbon Plan,” said Katharine Kollins, president of the Southeastern Wind Coalition. But she flagged what appeared to be a lengthy and probably unnecessary study period in the new Duke filings.

“What all of the developers need is certainty and a path to market,” she said. “I think we need to make sure that we don’t get caught in a loop of trying to gather information, and bringing that back to the Utilities Commission, and then gathering more information.”

Duke also left its summer plans for retiring its coal plants largely unchanged, even moving up the timeline for closing one of its largest, the Roxboro 4 unit in Person County, to 2029.

“It’s nice to see that large, dirty capacity go away quicker,” said Justin Somelofske, regulatory counsel for the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association. But, he added, “the bad news is… they’re doing that to use the transmission assets to interconnect new gas.”

And though regulators had ordered Duke to file with its latest proposal “a portfolio that meets the 70% reduction by 2030,” as mandated by law, the utility doesn’t really do so. Instead, it appears to suggest in just one chart on one page that resources planned by 2035 could be built five years earlier.

“We were very happy with the [Utilities] Commission order requiring Duke to do that,” said Somelofske of the 2030 blueprint. “But it feels like Duke was checking a box, instead of making an earnest effort to find a viable path to achieve 70% by 2030.”

A Duke spokesperson didn’t respond to a request for comment before this story was published. But the company’s filing makes clear it prefers a pathway to cutting its pollution 70% by 2035, if not 2037. That plan, it writes, is the “most reasonable, least cost, and least risk portfolio for planning purposes.”

As they have in the past, advocates say they’ll scrutinize Duke’s load projections as part of the Carbon Plan process this year. But the irony isn’t lost on them that much of the new demand is being driven by electric vehicle battery plants and other projects heralded as part of the clean energy transition. And some companies likely chose the state in part because of its commitment to decarbonizing the electricity sector.

“We don’t want to see Duke take a fundamentalist position to meet the challenge” of new demand, Somelofske said, “by doing what they’re comfortable with, and then potentially threatening future economic development.”

No matter what, the latest Duke filing is far from the last word on the subject. The state’s Utilities Commission has until the end of the year to greenlight or amend the Carbon Plan, and it has scheduled public and expert hearings through the spring and summer.

“We’re hopeful the Utilities Commission will require Duke to pursue a path that controls costs for customers,” Scott said, “while meeting North Carolina’s 2030 carbon emission reduction goal on time.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to provide more context on Duke Energy’s proposed power plant investments.

NATURAL GAS: The U.S. Department of Energy pauses all approvals of new liquefied natural gas export facilities to further review their climate and other impacts, in a process expected to last up to 15 months. (E&E News, Politico)

ALSO: An Arizona judge clears the way for Salt River Project to expand a natural gas power plant near a historically Black community following a two-year legal fight and charges of environmental racism. (Arizona Republic)

GRID:

SOLAR: While most state and local regulations are clear that developers or owners of utility-scale solar projects must pay to decommission them, some rule complexities can fuel local opposition to projects. (Inside Climate News)

EMISSIONS:

OFFSHORE WIND: Federal agencies publish plans to protect a critically endangered whale species amid East Coast offshore wind development, a strategy that includes artificial intelligence and passive acoustic monitoring. (Associated Press)

CLIMATE:

ELECTRIC VEHICLES: Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm believes drivers will warm to electric vehicle adoption as costs come down and convenience benefits are realized. (ABC News)

NUCLEAR: An Ohio nuclear plant owner and federal regulatory staff oppose two citizen groups’ attempts to formally intervene in a request to extend the plant’s life through 2046. (Energy News Network)

BUILDINGS: National Grid picks a Boston public housing complex, the Dorchester neighborhood’s Franklin Fields Apartments, for the city’s first networked geothermal heating system. (Mass Live)

OIL & GAS: The Biden administration temporarily halts some permits for new liquified natural gas export terminals on the Gulf Coast as it instructs the Energy Department to consider their climate effects. (Louisiana Illuminator, Washington Post)

ALSO: LanzaJet opens a sustainable jet fuel refinery in Georgia, boosted by $18 million in federal funding and $50 million from a Bill Gates-led clean energy funding group. (Columbus Ledger-Enquirer)

EMISSIONS:

SOLAR:

ELECTRIC VEHICLES:

OIL & GAS: Texas regulators identify dangerous levels of a carcinogenic chemical in water erupting from an old oil well. (Houston Chronicle)

UTILITIES:

ACTIVISM: Young climate activists converge on Tallahassee to lobby the Florida legislature for worker protections, clean energy and other bills to address climate change. (Miami Herald, WUSF)

CARBON CAPTURE: A British power plant company announces it will open a new carbon capture business headquartered in Houston, Texas. (Power Technology, news release)

INFRASTRUCTURE: A Tennessee commission finds the state needs $68 billion in infrastructure improvements, with half of that just for transportation and utility infrastructure. (WBIR)

CLIMATE:

POLICY: As Vermonters struggle to pay for climate-related disasters, many state representatives are supporting legislation to make the fossil fuel industry pay into a climate change “superfund.” (WCAX, VT Digger)

ALSO: Connecticut has begun offering payments to help environmental justice and ratepayer groups participate in utility regulatory proceedings, but nonprofits say the program is only the first step toward encouraging more diverse participation. (Energy News Network)

PIPELINES:

FOSSIL FUELS:

BUILDINGS:

CLIMATE:

OFFSHORE WIND: Two small New York businesses — an efficiency component manufacturer for coal plants and an ironworks — describe how the offshore wind development push benefits them, as well as the workforce development challenges of working offshore. (RTO Insider, subscription)

CLEAN ENERGY: Sunderland, Vermont, becomes the southern half of the state’s first “green procurement town,” meaning it plans to opt for carbon-free alternatives for equipment, services and power. (news release)

ELECTRIC VEHICLES: In Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, an armored truck company receives about $1.3 million in state-directed Volkswagen settlement funds to replace six diesel trucks with battery-electric models and install charging infrastructure. (Lehigh Valley Live, news release)

OIL & GAS: The Alaska Indigenous community closest to the Willow drilling project withdraws its opposition to the development on the condition that ConocoPhillips protects subsistence resources. (Northern Journal)

ALSO:

CLIMATE:

URANIUM: The Havasupai Tribe and Arizona advocates oppose the Pinyon Plain uranium mine’s reopening near the Grand Canyon, saying it could contaminate groundwater. (Arizona Republic)

SOLAR:

CLEAN ENERGY: A Wyoming county seeks public comment on two utility-scale solar and wind projects proposed for private land. (Douglas Budget)

ELECTRIC VEHICLES:

HYDROGEN:

GRID: Storms batter Hawaii utility lines and generators, leading to power shortages and outages. (KHON)

COMMENTARY: A California advocate urges the state to incentivize rooftop solar to offset net metering cuts, saying it would solve distributed generation’s equity problem while lowering utility bills and fighting climate change. (Los Angeles Times)

Environmental groups filed an appeal Thursday, challenging recent decisions by an Ohio regulatory commission to allow drilling under a state park and two state wildlife areas.

Those decisions currently call for sections of Salt Fork State Park, Zepernick Wildlife Area and Valley Run Wildlife Area to be leased to the highest and best bidder, with the bidding period set to start in January.

Among other things, the groups say the Ohio Oil and Gas Land Management Commission failed to consider all of the factors it was required to weigh under state law. The groups also allege that the commission failed to provide an opportunity for public hearing under state law.

Plans to drill under Ohio state parks and wildlife areas were jump-started earlier this year by House Bill 507, which began as a two-page bill about poultry regulations and grew to more than 80 pages when lawmakers heaped in provisions about natural gas and other unrelated topics last December. Environmental groups challenged the constitutionality of the law earlier this year, and that case is still pending.

The new case appealing the commission’s decisions was filed on Nov. 30 with the Franklin County Court of Common Pleas. A notice of appeal was also filed with the Ohio Oil and Gas Land Management Commission.

Parties to the appeal include Save Ohio Parks, the Ohio Environmental Council, the Buckeye Environmental Network and Backcountry Hunters and Anglers. Lawyers at Earthjustice are acting as counsel, and the Ohio Environmental Council also has its own attorneys on the complaint.

HB 507 would have required approval of drilling under state-owned lands until the commission adopted a standard lease form and other rules to allow drilling on different parcels.

Now, under the law, Ohio statutory law calls for the commission to consider nine factors, including environmental impacts, effects on visitors or users of state-owned lands, public comments or objections, economic benefits and more. Commission Chair Ryan Richardson also recited those factors in an affidavit filed in the constitutional challenge case.

The opponents’ appeal alleges that the commission failed to duly consider all those factors. The commission also did not allow people attending the meetings to present testimony in opposition to particular proposals.

Even after the Ohio Oil and Gas Land Management Commission adopted rules this spring, comments by its members indicated they still viewed HB 507 as a legislative mandate preventing them from rejecting parcel nominations outright.

“We’ve been directed to open these lands up,” Richardson said at a Sept. 18 commission meeting.

In a similar vein, commission member Jim McGregor told the Energy News Network this summer, “we have a mandate from the legislature that says we shall lease public lands for fracking.”

The commission did not discuss all the statutory factors for voting either yes or no at its Nov. 15 meeting. Yet it voted to allow opening up lands under the state park and wildlife areas for bid next quarter. No written opinion explaining the decisions has been posted on the commission’s website.

“The commission is not required to submit a written opinion, and they are not expecting to write one,” said Andy Chow, spokesperson for the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, in response to a question by the Energy News Network the next day. “And there is no appeals procedure.”

“The Commission’s refusal to issue a written decision, failure to engage in meaningful discussion of the statutory criteria, and its belief that decisions are not appealable, show a concerning disregard for the process and rigor contemplated by their statutory mandates,” said Megan Hunter, a lawyer for Earthjustice who is representing opponents in the appeal and in the constitutional challenge case.

“As seen in the Commission’s meetings, the Commission did not publicly consider all nine statutory factors prior to opening up Salt Fork State Park, Valley Run Wildlife Area, and Zepernick Wildlife Area for oil and gas development. The Commission should be held accountable for this failing,” she added.

Automaker Stellantis has made some big climate promises. But behind the scenes, it’s lobbied against efforts to hold the company accountable to those commitments. So have dozens of other major companies, according to a new report from the environmental group InfluenceMap.

The maker of Chrysler, Jeep and other big-name auto brands pledged last year that half of the vehicles it sells will be electric by 2030. It’s building two electric vehicle battery plants in the U.S. to help achieve that goal, and it also agreed to protect workers’ futures in the EV transition in its recent deal with the United Auto Workers. And those EV goals are just part of its plan to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2038.

But away from the public eye, Stellantis is actually working against stronger vehicle emissions regulations, InfluenceMap found. Just this summer, the company told the U.S. EPA it opposed stronger greenhouse gas emissions regulations for heavy-duty vehicles, reports the nonprofit news outlet Sludge. It later pushed for weaker emission standards for light-duty vehicles, too.

The automaker isn’t alone. InfluenceMap’s report accuses dozens of other companies of “greenwashing” as they publicly claim they’re shooting for net-zero while working against climate action behind the scenes. The list includes Delta Air Lines, ExxonMobil and several utilities and manufacturers.

You can find the whole report here, and read more from Sludge.

🖥️ AI’s energy impact: The proliferation of AI-powered smart devices is bound to spike energy demand; analysts recently speculated that the technology’s use worldwide could someday match all of Ireland’s energy use and significantly drive up global emissions. (Verge)

💰 A new life for fossil fuel towns: A new analysis finds a big piece of wind, solar, battery and manufacturing investment spurred by the federal climate law is going to communities that have long been economically dependent on fossil fuels. (Washington Post)

🚘 EVs’ ups and downs: U.S. electric vehicle sales are up nearly 50% so far this year compared to last, though clean energy and EV manufacturers still face mounting financial and supply chain challenges. (Canary Media, E&E News)

🤑 Money (and fossil fuels) to burn: Twelve of the world’s wealthiest people produce greenhouse gas emissions equal to more than 2 million homes via their private jets, financial investments, and other luxury purchases, researchers find. (Guardian)

🪖 Pumping up heat pumps: The Biden administration deploys the Defense Production Act — a measure usually used to boost manufacturing during wartime — to speed manufacturing of electric heat pumps. (The Hill)

🚪 Meet the solar sales bros: A wave of door-to-door solar “sales bros” with little actual knowledge of the technology and a tendency to lie to close sales could threaten consumer confidence in the clean energy transition. (Time)

♻️ Second wind: In downtown Cleveland, old wind turbine blades are getting a new life as benches and tables. (Bloomberg)

👀 Peer pressure on climate: While a new climate agreement between the U.S. and China lacks specific goals, concrete promises from the two nations could encourage further action at this year’s COP28 climate summit. (Inside Climate News)

🔋 A new life for EV batteries: A California project tests using old electric vehicle batteries to store solar power — a recycling solution that could reduce the need for mining more materials. (Grist)