A surge of housing development in a Boston suburb is providing evidence that natural-gas bans and strict energy-efficiency standards do not slow new construction or make it more expensive. Indeed, these guidelines can even boost the growth of affordable housing, say local advocates.

In 2024, Lexington, Massachusetts, banned gas hookups in new construction and adopted a stringent building code that requires high energy-efficiency performance. Yet these regulations have not stopped the town of roughly 34,000 from permitting some 1,100 new units of housing — 160 of which will be affordable — over the past two years.

“Opponents said, ‘It’s going to cost so much, you’re going to stop the development of affordable housing.’ But that clearly wasn’t the case,” said Mark Sandeen, a member of the town select board and the board of the Lexington Affordable Housing Trust.

As Massachusetts aims to get to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, the state has for several years prioritized policies that encourage the transition away from fossil fuels, particularly natural gas, which heats about half of the state’s homes. In 2022, Massachusetts launched a pilot program allowing 10 communities — including Lexington — to prohibit the use of fossil fuels in new construction and major renovations. In late 2023, utilities regulators issued an order that makes explicit the state’s goal of getting off natural gas, and lays out strategies and principles for reaching this goal.

Detractors, however, have consistently argued that requiring or even heavily encouraging all-electric construction would make housing more costly and difficult to build at a time when Massachusetts is facing an acute housing shortage. In 2022, then-Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, memorably said the idea of fossil fuel bans gave him “agita,” so worried was he that such municipal regulations would suppress housing growth.

Similar battles have played out across the country, from California to New York.

There is plenty of evidence that electrified, highly efficient homes don’t need to come with a price premium.

A 2022 study by think tank RMI found that, in Boston, all-electric homes are slightly less expensive both to build and to operate than mixed-fuel homes — and that was before Massachusetts’ investor-owned utilities adopted lower wintertime rates for homes with heat pumps. In 2023, Massachusetts-based advocacy group Built Environment Plus found that building larger multifamily and affordable housing developments “net-zero ready” — that is, highly efficient and with all-electric heating — costs about 4% less up front than the conventional approach.

After Lexington changed its zoning rules in 2023 to allow more multifamily development, its energy regulations did not, as naysayers had feared, deter developers from taking advantage. The planning board has approved nine projects, ranging from a proposal to redevelop an unused commercial space into a seven-unit building, to a complex combining 312 residential units with 2,100 square feet of retail space.

The new construction will include both rental units and condos available to purchase that will, in total, increase available housing in town by 9%. Much of the new housing will be market-rate, and Lexington — where the median condo went for $915,000 in the first quarter of 2025 — is not an inexpensive place to live.

However, most of the construction driven by the new zoning is required to make 15% of its units affordable. On top of these private projects, the town has decided to develop a municipally owned property into a 40-unit affordable housing development, bringing the total number of affordable units on the horizon to about 200.

The municipal project will include four residential buildings designed to be energy-efficient and to minimize the square footage of halls and other common areas, which will reduce the cost of heating and cooling these spaces. Solar panels on the roofs will offset the electricity consumed by the building’s heat pumps, said Dave Traggorth, principal with Causeway Development, the company chosen to develop the property.

“Ultimately, what the tenant is paying for in their electric bill is really just cooking and lights,” he said. “It really reduces the utility bills for residents.”

All of these new projects — market-rate and affordable — will be prohibited from using fossil fuels to run furnaces or other appliances because of the town’s requirement that new construction be fully electric.

The town has also adopted an optional, more rigorous version of the state building code that requires new, multifamily projects over 12,000 square feet — which applies to most of those in the pipeline in Lexington — to build to passive house standards, which require a very well-sealed building envelope and dramatically reduced energy use compared to a conventionally built structures.

“This is what you can do at the local level,” said Lisa Cunningham, cofounder of climate advocacy organization ZeroCarbonMA.

While Lexington is a particularly active town, the other nine communities that have banned fossil fuels in new construction have all reported that the rules have posed no obstacle to development, Cunningham said. Restrictive zoning and antidevelopment sentiment among residents are much more pressing problems, she said.

For the eventual residents, the benefits go beyond the knowledge that their homes are helping cut emissions. Homes designed to passive house standards use far less energy than those that are conventionally built, creating ongoing savings for homeowners and tenants, and have been found to generally have better indoor air quality. When the power goes out, these well-sealed buildings can keep interior temperatures comfortable for days.

It is no accident that residential developers were ready to jump when opportunities opened up in a town with stringent efficiency and electrification rules. Massachusetts has been laying the groundwork for years, said Lauren Baumann, director of sustainability and climate initiatives for the Massachusetts Housing Partnership, a nonprofit that works to expand affordable housing.

“There has been this deliberate effort to develop an ecosystem to support this kind of construction,” she said.

In 2019, the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center awarded $1.73 million in grants to eight affordable, multifamily projects to help accelerate the adoption of passive house standards in multifamily construction by demonstrating that the approach makes financial sense. That same year, the state’s energy-efficiency program administrator, Mass Save, launched an initiative offering money to multifamily projects for feasibility studies, energy modeling, and analyses of post-construction energy performance.

These incentives gave architects and contractors a lower-risk way to become familiar with a new approach to building. And familiarity, in this case, bred knowledge, skills, and enthusiasm.

“Those early project pilots really did give people the experience they needed in order to feel comfortable,” Baumann said. “We just saw an explosion of interest.”

Traggorth has seen this evolution in his work. Five years ago, he said, if he approached a contractor to discuss building to passive house standards, he was often greeted with confusion. Now, “every contractor that’s building multifamily has a couple of projects that have been passive house certified,” he said. “They have learned their lessons.”

San Francisco already requires most new buildings to eschew gas and run solely on electricity. Now, the metropolis is moving to ensure that substantial renovations in existing buildings are also all-electric.

Last week, the city and county’s Board of Supervisors completed the first of two votes to pass the All-Electric Major Renovations Ordinance, a climate-forward building standard that will apply to commercial and residential structures. The initial 11–0 vote was a resounding sign of approval; the final hearing is likely to occur Sept. 2, according to the San Francisco Environment Department, the agency that developed the rules.

“We can’t build the San Francisco of the future with fuel from the past,” Board of Supervisors President Rafael Mandelman said in a statement. “This legislation picks up where we left off with the All-Electric New Construction ordinance and affords us the opportunity to eliminate the use of fossil fuels in our existing buildings, improve indoor and outdoor air quality, and make San Francisco a safer, healthier, and more resilient place to live and work.”

The proposed ordinance was years in the making, but the city is now fast-tracking its approval before a new statewide pause on updates to building codes kicks in. Under the law, signed in June, San Francisco and other jurisdictions in the Golden State have only until Oct. 1 to adopt stronger building codes unless they claim an exception.

San Francisco can’t meet its climate goals unless it moves buildings away from fossil fuels. The city has vowed to slash carbon pollution by 61% from 1990 levels by 2030 and to achieve net-zero emissions by 2040 — five years faster than California as a whole. Buildings in San Francisco account for 44% of the city’s planet-warming pollution, the largest emitter after transportation, at 45%.

If enacted, the new ordinance will affect projects that are similar in scope to new construction, including additions as well as renovations that rip out mechanical systems. It won’t bear on single equipment replacements, however, like replacing a gas furnace.

The ordinance essentially “closes a loophole” in the new construction requirement, Cyndy Comerford, climate program manager at the SF Environment Department, told Canary Media. For example, on the same downtown parcel of a five-story brick building, a whopping 46-story glass edifice was recently added, she said. “That addition was allowed to have gas in it when it was a totally separate building.” The new ordinance would put a stop to similar cases in the future.

Lawmakers are leaving room for exceptions to the all-electric standard, including restaurants that use gas for cooking, buildings composed of 100% affordable housing units (with gradual compliance after July 2027), and projects that can’t get enough power from the utility in time. Building owners would seek exemptions from the SF Environment Department.

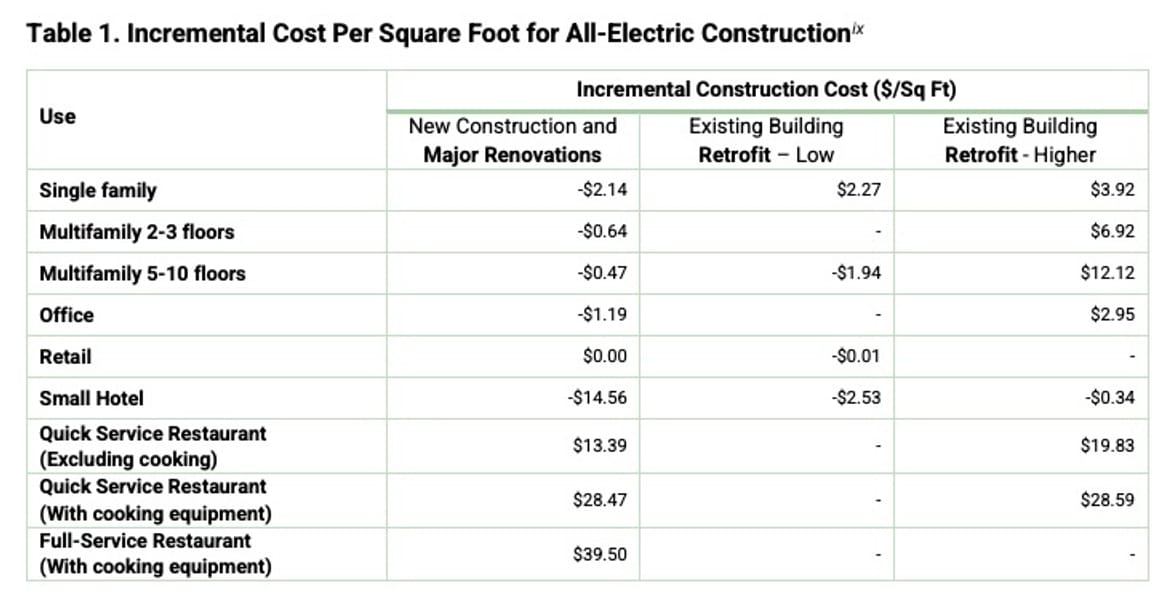

In many cases, the cost of all-electric construction is actually lower than that of mixed-fuel buildings, according to the department. Summarizing several analyses, it estimates that newly built or majorly renovated all-electric single-family homes are cheaper than conventional construction by more than $2 per square foot, on average.

Contrast that to the higher estimated costs to switch to all-electric appliances after construction. The department estimates such retrofits would cost San Francisco homeowners an added $2 to $4 per square foot.

And all-electric retrofits are coming.

In 2023, San Francisco Bay Area air regulators passed landmark rules to phase out the sale of gas-burning water heaters by 2027 and furnaces by 2029 for single-family homes. When old combustion appliances conk out after those dates, homeowners will need to foot the bill to replace them with zero-emissions units. The same will hold for multifamily building owners by 2031.

“Developers aren’t always incentivized to think [about] who’s going to be living in this property 10 or 15 years from now,” said Tyrone Jue, director of the SF Environment Department. “And that’s where government has to step in to say … ‘Yes, we want you to build housing, but we want you to do it smartly so that we don’t end up having to carry the financial burden down the road.’”

Fossil gas also carries heavy social costs. In addition to contributing to an increasing drumbeat of climate disasters, burning fossil fuels in home appliances releases a slew of pollutants, from carbon monoxide to nitrogen oxides, that concentrate indoors and spill outdoors. These by-products can lead to respiratory disorders, cardiovascular disease, and premature death. One in eight childhood asthma cases are linked to gas stoves. All-electric equipment doesn’t emit these compounds.

“As a city, we’re responsible for the well-being of our citizens,” Comerford said.

Gas lines are also a particular liability in the earthquake-prone region. Liquefaction of the earth can sever underground pipelines, which are more prone to damage than the city’s electrical system, Jue said. In a 2020 report, utility Pacific Gas & Electric estimated that after a 7.9 earthquake, it would take up to six months to restore gas services citywide; electricity could be brought back on line in two weeks.

The all-electric renovations ordinance comes as the federal government is rolling back environmental regulations and pushing for more fossil fuel use, not less. “This is a moment for cities like San Francisco to step up,” Jue said. “And this is San Francisco drawing a clear line, not waiting for permission from Washington to protect our people, our health, and the planet.”

Southern California can keep a landmark rule that’s meant to spur the electrification of certain boilers and water heaters across the smog-choked region.

Late last week, a federal court upheld the first-in-the-nation regulation, which will gradually eliminate emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx) from more than 1 million fossil-gas appliances in the South Coast Air Quality Management District that covers greater Los Angeles. It applies to light-industrial and commercial boilers, steam generators, and process heaters, as well as residential pool heaters and tankless water heaters.

Opponents of the rule, led by gas-appliance makers and building trade groups, had sued in December to invalidate the standards.

“This decision recognizes our air regulators’ long-established authority to adopt life-saving protections — and sends an undeniable signal to manufacturers and businesses that the future of California’s industrial sector is electric,” Candice Youngblood, an attorney for Earthjustice, which intervened to defend the rule in court, said in a July 21 statement.

The measure is ultimately expected to reduce pollution by 5.6 tons of NOx per day — the same as halving smog-forming emissions from cars in the region.

Advocates say the ruling could help to reenergize efforts around the country to replace fossil-fuel-burning equipment with electric heat pumps and other clean technologies in homes and commercial operations.

Such initiatives have stalled since April 2023, when a different federal court struck down Berkeley, California’s pioneering ban on gas hookups in new buildings. The court said the city’s gas ban was preempted by the federal Energy Policy and Conservation Act and thus wasn’t valid. The groups suing to stop Southern California’s zero-emission boiler rules pointed to Berkeley to claim that the measure also conflicted with the federal energy-efficiency law.

On July 18, the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California found otherwise. The court clarified that the Berkeley ruling is “very narrow” in scope and applies to building codes that concern energy use. The measure in Southern California regulates only appliances’ emissions. Put another way, “It’s about what comes out of the appliance — not what goes in,” explained Nihal Shrinath, a staff attorney for the Sierra Club, which also intervened in the case.

Last week’s court ruling “is a really big deal,” both because it enables significant emissions reductions and it affirms that air-quality measures can withstand such legal challenges, he told Canary Media.

“We think there’s probably been less activity by air districts and local municipalities, in terms of advancing [zero-emission rules], because of the fear of litigation,” he said. The South Coast Air Quality Management District itself recently rejected a plan to curtail pollution from certain residential space and water heaters following an opposition campaign led by utility giant SoCalGas.

The California air district spans large portions of Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, and San Bernardino counties. More than 17 million people live in the region, where high levels of NOx contribute to some of the worst health-harming smog pollution in the country.

In June 2024, regulators adopted the zero-emission rule for small boilers and large water heaters in homes and businesses as part of its decadeslong mission to meet federal air-quality standards.

Gas-burning appliances covered by the rule account for about 9% of all NOx emissions from stationary sources in the area. They include an estimated 710,000 residential pool heaters and 300,000 tankless water heaters, as well as 60,000 light-industrial and commercial boilers and water heaters at places such as dry cleaners, restaurants, warehouses, and hospitals.

While the measure doesn’t explicitly ban or require any specific technology, the most realistic way for anyone to comply is by replacing their gas-fired appliances with alternatives like ultra-efficient heat pumps or modern electric-resistance boilers.

The limits on NOx emissions are designed to ramp up over time, starting in 2026 for new small units installed in new buildings and extending to new high-temperature units installed in existing facilities in 2033. The drawn-out timeline is meant to allow small businesses and homeowners some flexibility as they phase out their current equipment. It also gives manufacturers of zero-emission technologies enough time to develop and scale up production to meet the new demand.

Critics of the measure, including dry cleaner associations and building contractors, have argued that switching out gas-burning equipment and upgrading buildings’ electrical systems would impose a “significant financial burden.” The air district has estimated that the transitioning to zero-emission equipment will cost companies and households about $49 million to $97 million per year — though the air district will provide rebates to help defray some of those expenses. Industrial heat pumps can also deliver lower operating costs than gas boilers because the electric tech is much more energy-efficient.

Regulators and environmental groups maintain that such rules are necessary both to improve public health within the district and to accelerate the market nationwide for emissions-free industrial equipment. Last week’s court ruling ensures such efforts can continue.

A home electrification and solar pilot program for lower-income Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard residents is cutting participants’ energy bills nearly 60% and is expected to inform Massachusetts’ ongoing efforts to bring renewable energy and energy efficiency to all households.

“What the commonwealth has to have available, if we’re going to even hope to achieve our climate goals, is that there have to be options for people at every income level,” said Maggie Downey, chief administrative officer of the Cape Light Compact, the organization that administered the pilot.

The program, known as the Cape and Vineyard Electrification Offering, gave solar panels to all 55 participating households and heat pumps to 45 of those, most at no cost and some with a low co-payment, depending on income levels. Twelve households also received batteries, and some got electric dryers and stoves, to transition the homes completely off fossil fuels. Installations began in January 2024, and the final one wrapped up in May 2025.

The results: The average household is saving some $150 per month on energy costs and reducing net electricity use by 59% by getting much of its needed power from the on-site solar panels, according to an analysis published by the consultancy Guidehouse at the end of last month. Perhaps unsurprisingly, participating residents are quite satisfied with these outcomes, giving the program an exceptionally good “net promoter score” of 71%.

“My costs are drastically lower,” said Judy Welch, a homeowner in the Cape Cod town of Chatham who was one of the first folks to sign on for the upgrades. “In the summer now, I don’t have any bills, and I have the air conditioning on the whole time.” Her winter energy bills have also dropped to nearly zero thanks to the solar-powered heat pumps; previously, Welch paid around $500 a month to run electric baseboard heating.

Massachusetts has long had strong incentives for renewable energy and been a leader in policies promoting energy efficiency. The state has had less success, however, in helping lower-income households realize the benefits of these measures. At the same time, Massachusetts residents — especially those who make less money — face some of the highest energy burdens in the country. On Cape Cod, households making less than one-third of the area median income spent an average of 27% of their income on energy as of 2023, according to data from the U.S. Department of Energy. (An updated figure is unavailable because the federal tool that provided this data is no longer live.)

The Cape and Vineyard Electrification Offering was conceived of as a way to overcome the sometimes unmanageable up-front cost of efficiency and clean energy upgrades, and to amplify the impact of individual technologies by deploying them together. Solar panels would keep down the cost of operating heat pumps, and batteries would maximize the amount of zero-cost electricity available to each home.

“It’s all bundled for the participant in a way that makes sense and optimizes all these different systems and combines them through one program,” said Todd Olinsky-Paul, senior project director for the Clean Energy Group, a Vermont-based nonprofit that advocates for a just energy transition. “I haven’t seen that anywhere else.”

The pilot was designed and offered by the Cape Light Compact, a unique regional organization that negotiates electric supply prices and administers energy-efficiency programming for the 21 towns on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard. The compact proposed versions of the pilot in 2018, 2020, and 2021, before the state gave it the go-ahead in 2023.

The version that was finally approved called for 100 homes to participate in the pilot. As the effort rolled out, however, planners realized how challenging it is to deploy a standard package to houses with a wide range of ages and conditions. In some cases, interested homeowners decided against participation when they realized they would have to pay more than they hoped or discovered their yards were too shaded to generate much solar power. Some who did participate needed mold remediation or roof replacements; others were unable to receive batteries because they didn’t have basements.

“There is really no single solution for these questions,” Downey said. “It is so site-specific and customer-specific.”

Ultimately, 55 homes enrolled, as the unanticipated roadblocks raised the expected cost of serving each participant. On average, the Cape Light Compact spent about $45,700 on each heat pump installation, $30,000 on each solar installation, and $33,000 on each battery system, according to preliminary calculations.

These figures raised some questions at a recent meeting of the compact’s governing board, at which the Guidehouse report was presented. Downey acknowledged the cost, but pointed out that the need to transition off fossil fuels is inevitable — and comes with a price tag.

“You cannot hide the expense of what we have in front of us to deal with,” she told the board.

The report offers suggestions for improving any future iterations of the initiative. Pilot participants were prohibited from enrolling their solar systems in the state’s net-metering offering, and therefore their compensation for excess energy sent back into the grid was between 5 cents and 10 cents per kilowatt-hour, rather than at least 25 cents per kilowatt-hour. The evaluation suggests that future programs should allow the use of net metering to improve financial benefits even further. The report also suggests improving coordination among the various installers involved to make the process run more smoothly for participants.

The Cape Light Compact will present the results at the August meeting of the state Energy-Efficiency Advisory Council, the group responsible for writing Massachusetts’ triennial energy-efficiency plan. From there, the council will decide how to use the information to guide future equity-focused electrification efforts and determine the appropriate amount of financial support for households at different income levels.

“The results show that there are savings, and that energy burdens are reduced by more than 50%, when you pair it all with solar,” Downey said. “If we want to have low- to moderate-income customers come with us, we need to have options — that’s all part of the conversation.”

Have you been sitting on the sidelines, waiting to decarbonize your home and commute?

It may be time to jump into action.

The “Big, Beautiful Bill” that President Donald Trump signed on July 4 sets early expiration dates for a slew of federal tax credits that have made it easier for millions of Americans to switch to clean and typically cheaper-to-run electric appliances and EVs, make efficiency upgrades to their homes, and put solar panels on their roofs. After the end of the year — and even sooner for EVs — none of those incentives will be available.

“We’re at a ‘use it or lose it’ point,” said Skip Wiltshire-Gordon, director of government affairs for policy strategy firm AnnDyl Policy Group. He’s encouraging people to start talking to contractors to figure out which upgrades make sense for them and to get on installers’ schedules.

Besides improving indoor air quality, switching to a heat pump lowers energy bills by hundreds of dollars for the majority of households, according to electrification nonprofit Rewiring America. Savings climb still higher by installing heat-pump water heaters and rooftop solar. These benefits are especially salient as utility bills rise nationwide, a trend that experts expect the new law to exacerbate.

In addition to the tax credits, households may also be able to access federal home-energy rebates, depending on their state; that Biden-era program was untouched by the new legislation.

Here’s a run-through of the federal incentives that are, for now, available to help you electrify your life.

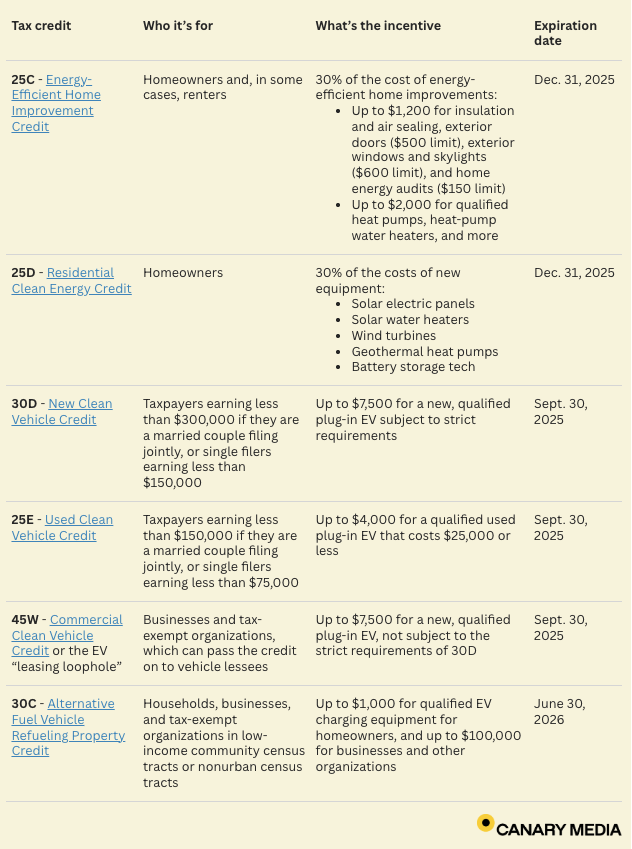

The Energy-Efficient Home Improvement Credit (25C) can get you up to $2,000 off your federal taxes for a qualifying heat-pump heater/air conditioner or heat-pump water heater, and separately, up to $1,200 on other energy-efficient upgrades, including insulation and air-sealing materials, windows, and exterior doors. The credit will even help you pay for an energy audit to diagnose your home’s biggest upgrade opportunities. You can claim a total of $3,200 this year. Under previous law, the credit renewed annually, so before the “Big, Beautiful Bill,” you could claim it every year until 2033. No longer. Expires: Dec. 31.

The Residential Clean Energy Credit (25D) takes 30% of the cost of a clean energy installation off your federal tax bill, with the actual amount uncapped. What tech counts? Solar photovoltaic panels, solar water heaters, home battery storage, geothermal heat pumps, and even home wind turbines. Feel free to go wild; you can use the tax credit for multiple projects in the same year. Expires: Dec. 31.

The New Clean Vehicle Credit (30D) can get you $7,500 off your federal tax bill for a brand-new, qualifying EV model. However, your household must earn less than $300,000 for married couples filing jointly, or $150,000 for single filers. You can get the discount on-site when you make your purchase. Expires: Sept. 30.

The Used Clean Vehicle Credit (25E) can lop up to $4,000 off your federal tax bill for qualifying pre-owned EVs. The income maxima are half of those for 30D: $150,000 for married couples filing jointly and $75,000 for single filers. You can get the discount right at the dealership. Expires: Sept. 30.

The Commercial Clean Vehicle Credit (45W) of up to $7,500 can’t be claimed by consumers directly but still gives them a fiscal advantage. Auto dealers are able to take the federal tax credit themselves and pass on the savings to leasing customers. Called the EV “leasing loophole,” the credit can be used for vehicles that don’t meet the stringent requirements needed to claim 30D. Expires: Sept. 30.

The Alternative Fuel Vehicle Refueling Property Credit (30C) delivers up to $1,000 off your federal tax bill to install qualified EV charging equipment if you live in an eligible area. Expires: June 30, 2026.

Here’s a summary table to easily look up what the tax credits cover:

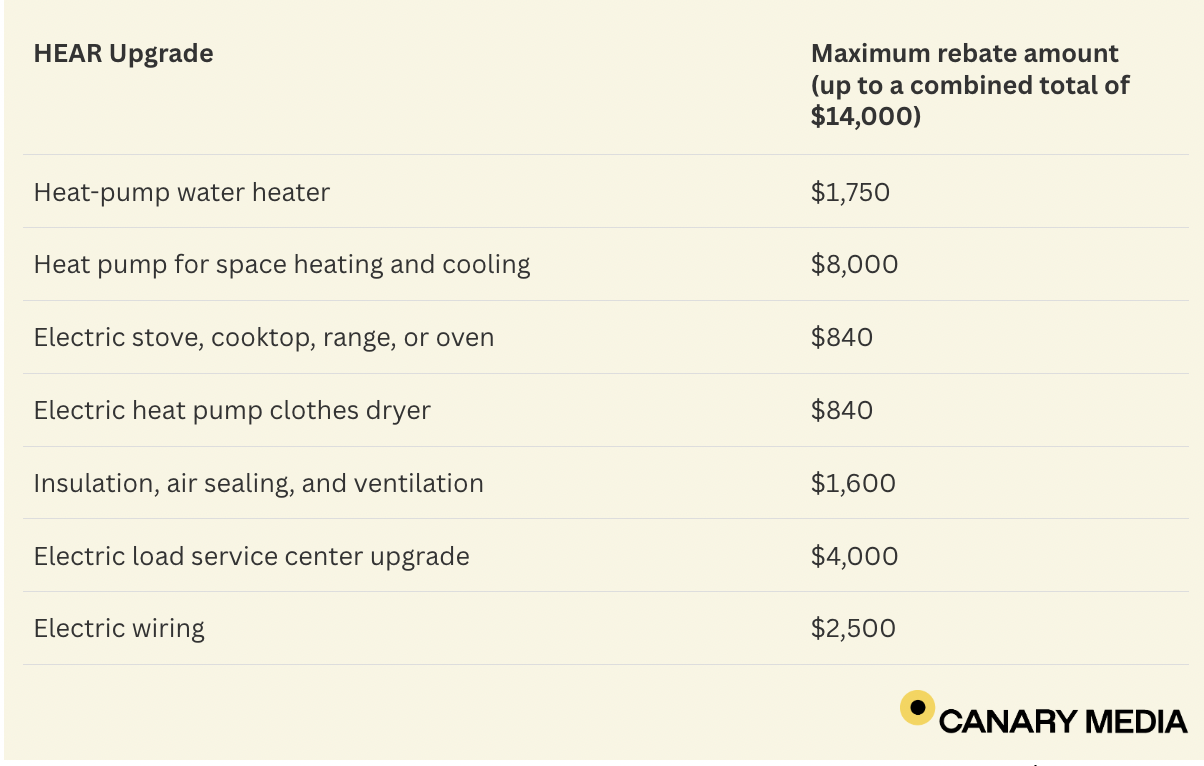

The $8.8 billion federal Home Energy Rebates program is targeted to low- and moderate-income families (earning less than 150% of the area median income) and comes in two flavors.

The Home Electrification and Appliance Rebate (HEAR) program provides qualified households with up to $14,000 in discounts for a wide range of efficient electric appliances and enabling upgrades — see the table below for an overview. Up to 100% of costs are covered for households earning less than 80% of the area median income, and up to half of costs for those that make 80% to 150% of the area median income.

The Home Efficiency Rebate (HER) program, also known as HOMES, can provide up to $4,000 — or $8,000 for lower-income households — for whole-home efficiency projects that are modeled to reduce energy use by at least 35%. The rebates can be even larger for actually-measured savings. Unlike HEAR, all households are eligible.

States and territories administer their own instances of the programs, and details vary, including eligibility requirements. The programs are still coming online. So far, five states — Georgia, Indiana, Michigan, North Carolina, and Wisconsin — plus Washington, D.C., have rolled out both HEAR and HOMES programs, making incentives available to residents, according to the Atlas Buildings Hub. Another seven states have launched just the HEAR program.

So check with your state energy office if home energy rebates are available or will be soon and how to qualify. In some cases, they’re going fast.

Home upgrades can be a beast, and Dec. 31 makes for a tight deadline, so the sooner you start exploring your electrification moves, the better.

You could kick the journey off by diving into the archives of this column, scheduling a home energy audit, and playing with a couple free online planning tools. Rewiring America’s personalized electrification planner lets you put in information, like your address and current appliances, and estimates the up-front costs and energy-bill impacts of going electric. The Green Upgrade Calculator by energy think tank RMI allows you to examine the financial expenses and carbon emissions you could avoid by replacing conventional fossil-fuel equipment with more efficient electric upgrades.

Check with your utility for local incentives in addition to the federal ones. Always shop around for at least three contractor quotes. The EnergySage marketplace can help connect you to some vetted options. Also, look for installers who specialize in whole-home electrification and can recommend cost-effective, holistic approaches.

Finally, find friends who have already made electrifying upgrades and yearn to give you advice. Seek out groups like Go Electric Colorado, Electrify Oregon, and Go Electric DMV for D.C, Maryland, and Virginia, which provide resources and electric coaches brimming with enthusiasm. They’ll be there to help you even after the tax credits are long gone.

As you wrap your home in insulation, ditch fossil-fueled furnaces for heat pumps, and trade in your gas-guzzling car for an EV, let me know how it goes! What challenges are you running into? What have you learned that you wished you knew at the start? How does it feel to be a part of the clean energy revolution? Reach out to me at takemura@canarymedia.com; I’d love to hear your stories.

Canary Media’s “Electrified Life” column shares real-world tales, tips, and insights to demystify what individuals and business owners can do to shift to clean electric power.

CENTENNIAL, Colo. — At a grassy city park this spring, professional landscapers sauntered between vendor booths, asking questions about the shiny new wares laid out before them: battery-powered push mowers, leaf blowers, string trimmers, chainsaws, and more. Some hopped on new standing and riding mowers to give them a spin.

Noticeably absent throughout it all was the scent and the roar of gas-guzzling equipment; the tools were all electric.

At the event hosted by the nonprofits Regional Air Quality Council and the Colorado Public Interest Research Group Foundation, landscapers were scoping out battery-powered tools to prepare for statewide regulations that kicked in this month. The first-of-their-kind rules, adopted in 2024, restrict the use of landscaping equipment with small gasoline-powered engines on public property during the summer — the state’s high-ozone season.

As you might guess from just a whiff of the noxious fumes, gas-fueled lawn and garden equipment are extremely polluting. Their combustion engines are a hazard not only to a stable climate, but also human health.

In 2020, nationwide, these machines belched over 68,000 tons of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and 350,000 tons of volatile organic compounds, according to the U.S. Public Interest Research Group Education Fund, referencing data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Together, the chemicals form lung-searing ozone, a key component of smog linked to respiratory problems and even premature death. The amount of NOx emitted by fossil-fueled lawn equipment is equivalent to the annual emissions from about 30 million cars, or more than a tenth of those registered in the country.

After personal vehicles and oil and gas operations, the third-largest source of ozone-causing pollutants in Colorado’s Front Range region is lawn and garden equipment, said David Sabados, spokesperson for the Denver-based Regional Air Quality Council, the lead air-quality planning agency for the area. These machines don’t have catalytic converters, he pointed out, so “they have an oversized footprint on our air-pollution problem.”

The Front Range, which includes Denver and Boulder, frequently exceeds federal air-quality standards for ozone — but it’s not alone.

Cities, counties, and states around the country are also pursuing cleaner air and quieter neighborhoods by limiting the use of gas-fired landscaping equipment, incentivizing electric options, or both. California has had a zero-emissions (i.e., electric) standard for newly manufactured leaf blowers, lawn mowers, and other small off-road engines sold in the state since 2024. Montgomery County, Maryland, banned the use of gas-powered leaf vacuums and blowers, effective July 1. And New York is considering a bill to deliver a financial boost to commercial landscapers who switch to electric tools.

Colorado’s new rules, called Regulation 29, don’t affect individual homeowners, but instead require landscapers who work on federal, state, municipal, and public school properties to use zero-emissions handheld tools and push mowers from June 1 through Aug. 31.

To keep grooming these grounds, contracted companies are replacing their gas gear with electric options as it wears out, which can happen in as little as three years.

Some landscapers say the switch has broad customer appeal. Certain clients prefer electric tools because they work from home and don’t want combustion equipment disrupting their calls. Others prize the environmental benefits.

“The community we serve is very Earth-conscious,” said Ed Johnson, division manager for landscape company Outdoor Craftsmen, which has transitioned two of its six maintenance crews to predominantly electric models. “There’s definitely been a desire” among customers, many in Boulder County, for landscapers to act as good stewards, he said.

Johnson added that it’s strategic to ease into electrification now rather than scramble to overhaul operations when stricter regulations come down in the future. This winter, the Colorado Air Quality Control Commission will weigh tighter restrictions on commercial landscapers working on private properties, The Denver Gazette recently reported.

Making the switch to electric equipment isn’t easy, though. Cost can be a barrier, a concern the industry raised when Regulation 29 passed last year.

“It’s a big investment for all the batteries,” said Brian Levins, manager at Designscapes Colorado, a landscape design, construction, and maintenance firm. “When you’re buying a battery, you’re basically prepaying gas for two years.” The company, which earned $45 million in revenue last year, has spent about $36,000 (after incentives) on handheld electric tools and charging gear for six of its 20 crews, he said.

Designscapes was able to take advantage of the 30% discount on electric lawn equipment that Colorado offers through participating retailers. Other landscaping firms have defrayed costs with grants from state and local agencies, such as Boulder County’s Partners for a Clean Environment program.

Another hurdle is figuring out how to keep the equipment charged.

Johnson has rigged up an equipment trailer with a portable power station from manufacturer Kress that can recharge batteries in as little as eight minutes. And Aurora, Colorado, landscaper Singing Hills has beefed up the electrical infrastructure at its home base to handle the added load from electrifying some of its equipment. That upgrade cost about $15,000, said Jake Leman, CEO of the 30-year-old company.

An added challenge to going electric is that gas versions are still more powerful for a couple types of equipment, like leaf blowers, Johnson of Outdoor Craftsmen said. But the electric tech “is coming along,” he noted. “It’s getting really, really close.”

Plus, electric landscaping equipment boasts a bevy of benefits. It’s safer for operators, who no longer have to breathe their tools’ fumes or go home with the stench clinging to their clothes. Leman has heard from some crew members that they enjoy being able to talk while operating an electric machine — uncomfortable to do over a firing engine — and they’ve praised the faster start up of electric tools compared with gas-powered options that require pulling a cord, he said.

The electric machines also require much less maintenance, Leman noted: “There’s not the filters and the belts and the fluids to change.” With savings on fuel and upkeep costs, Johnson estimated some of his larger equipment would pay back after 27 months of operation.

Some companies don’t have to deal with the challenging economics of replacing equipment. Jordan Champalou started his business, Electric Lawn Care, with primarily electric machines four years ago, when he was 19. “I enjoy not breathing in fumes all day,” he said.

He’s also able to save on energy costs and charge in between job sites using cheap renewable power from two solar panels he installed on the roof of the trailer in which he hauls his Stihl mowers, blowers, trimmers, and chainsaw. His leaf blowers are indeed less powerful than gas-fired versions, he said, but he’s found a solution: He slings two at once.

About a third of Champalou’s clients hire him because he uses electric tools, he said. “This year has been more than ever.”

Some commercial customers are now also breathing easier on landscaping days, says Levins of Designscapes. A few client buildings have ventilation systems that inhale air from close to the ground. With gas equipment, “we need to notify them before we go out there, because otherwise those fumes will get sucked into the air-intake [system] and distributed through the building,” he said.

Battery-powered zero-emissions tools don’t have that issue, Levins noted. “And those customers love that aspect of the electric equipment.”

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy, and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

In Richmond, California, Zenaida Gomez is ready to say goodbye to the gas stove in the apartment she has rented for over a decade. She has a hunch that the pollution it emits is exacerbating her 10-year-old son’s asthma attacks, and she has heard from public health experts and doctors who’ve said it probably is.

“I’ve learned that not only do we have contaminated air when we are outside in Richmond, but there’s contamination and toxins within our homes,” Gomez said in a recent phone call.

She started attending City Council meetings and organizing with her neighbors as a member of the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE) Action, because, she said, “I wanted something different. I wanted something better.”

But ACCE Action’s goal isn’t simply to get rid of gas stoves. In a city where about one in four people — nearly double the national average — suffer from asthma due in large part to pollution from heavy industry, the group wants to shut off or “prune” the lines that send natural gas into homes in some neighborhoods. The phenomenon is called “neighborhood-scale decarbonization,” and it’s just getting off the ground in California.

Pacific Gas & Electric, the utility in the area, is on board with the idea. It has expressed a willingness to spend a portion of the money it would otherwise use to maintain gas lines to help electrify the homes in the neighborhood that will no longer use the gas.

David Sharples, county director at ACCE Action, says the group is looking at different neighborhoods that PG&E has identified as likely candidates. Once the group chooses an area, it plans to run a pilot project with the goal of electrifying all the appliances and adding solar panels and batteries for up to 80 homes.

“We’re looking at the Coronado, Iron Triangle, and Santa Fe neighborhoods, which are working-class, Black and brown neighborhoods where ACCE has been organizing for years,” Sharples said. “They all have old gas lines that need to be replaced, so it represents an opportunity to electrify.”

To understand the appeal of neighborhood-scale decarbonization, which is also sometimes called “zonal decarbonization,” it helps to be able to envision the vast network of gas pipelines that exist under most cities in the Western U.S. That network holds a potentially explosive gas, and it requires constant, expensive upkeep.

California has pledged to install 6 million heat pumps by 2030 as part of its larger effort to reach net-zero by 2045. And while a rule will begin going into effect in the Bay Area in 2027 requiring that broken water heaters and furnaces be replaced by electric appliances, a similar rule was just rejected in Southern California.

Experts say a large-scale effort just makes more sense than a piecemeal approach in many parts of the state. And as dramatic as it might sound to transition a whole block or neighborhood off gas at once, the approach may also cost less overall and make it easier to employ people fairly.

Neighborhood-scale decarbonization has also been popular with lawmakers. Last fall, the California Legislature voted to adopt SB 1221, a bill that will enable up to 30 neighborhood-scale projects of this type over the next five years.

The catch is that most residents in the neighborhoods must agree to the change. While the state’s obligation to serve currently requires 100% approval, SB 1221 will lower the threshold to 67% as the pilot projects start rolling out. Several groups have begun the work of educating communities about the benefits of the switch.

In Albany, a city of about 20,000 people north of Berkeley, Michelle Plouse, the city’s community development analyst, has spent the last few years working with PG&E to pilot one of the first neighborhood-scale projects in the state. Using the gas line mapping tool developed by the utility, Plouse and other city staff worked with the Albany City Council to identify 12 potential blocks. This spring, they narrowed it down to three.

The goal, Plouse said, is to find blocks that are easier to electrify while also focusing on lower-income parts of the city, where residents are less likely to be able to afford to electrify.

“What will happen if we don’t decommission the gas line is that the cost of maintaining it will continue to increase over time, and the user base will drop as people electrify,” said Plouse. “The folks who don’t have the money to electrify will be stuck on gas that will get more expensive every year.”

The City of Albany received a grant from the U.S. Department of Energy for the project, and they’ve used the funds to support an outreach plan that involves a block party, a focus group, and a team that goes door-to-door in hopes of talking to everyone on the three blocks. “It’s going to be a lot of listening and a lot of connecting with different people,” said Plouse.

Rachel Wittman, a senior strategic analyst at PG&E, said the utility provided a letter of commitment in support of Albany’s DOE grant, but it won’t be providing financial support for the project.

Although the California Public Utilities Commission is soliciting interest from communities that want to take part in the SB 1221 pilot program, a spokesperson for the commission said it won’t have a list of potential sites until the second half of 2026, at the soonest.

The Albany project will begin before then, so it won’t likely be considered one of the 30 pilots, and Plouse said they’re hoping to get 100% of the residents to sign on. “What’s most likely is that we continue serving as a kind of first test run that can provide information for those pilots,” she said. If that doesn’t work, they may decide to wait until they only need 67% resident approval.

“Albany’s learnings from their efforts in community outreach and advocacy during this project will provide valuable insights that can inform zonal electrification outreach strategy,” said Wittman. “This applies not just for SB 1221 and PG&E, but for any utility or community.” She said over three dozen cities, counties, and other energy providers have reached out to the utility with interest in zonal decarbonization.

ACCE Action and others in Richmond hope its neighborhood-scale project — dubbed Clean Energy and Healthy Homes — will be included in the list of pilot projects, and it appears to have a good chance at making the list. If they’re able to decommission a gas line there, Sharples estimates that it could cost as much as $15 million to upgrade and electrify homes spanning a few different neighborhoods and provide them with solar power. He hopes PG&E will cover around 10% of that cost.

The Richmond City Council approved the effort in early 2024, but the remaining funding is still in question. Chevron, whose local refinery has been a major polluter for more than a century, entered into a settlement with the city for $550 million over the next 10 years to avoid paying a per-barrel tax on the oil it produces. ACCE Action wants to see a portion of that money spent on the neighborhood-scale project. The group has been hosting community events and engaging community members like Gomez.

Tim Frank, a representative of the Building and Construction Trades Council in the county, wants to see the project move forward because it could also create a model for so-called high-road work in the home-electrification space. Currently, unionized workers tend to do larger electrification projects, while one-off residential projects are done by smaller companies not affiliated with unions. While some pay their workers well, many hire temporary laborers and keep wages low.

Electrifying all the homes on one block allows for the efficiency and stability associated with larger projects while benefiting individual families. It’s also more cost-efficient because it allows for bulk purchases of supplies.

It’s a worthwhile experiment, Frank said. “We’re engaged, partly because we see the huge promise of this strategy and we want to help prove out the model and scale it up,” he added.

For Gomez, who has been talking to her neighbors about the possibility that all their homes could be upgraded and electrified at once, the biggest barrier is convincing them that it’s not a scam. Richmond’s low-income communities have seen their share of companies that go door-to-door trying to extract money from people who are stretched thin and working multiple jobs. Some clean energy providers have turned out to be imposters.

“It’s something they’ve never heard of before. So, people ask: Is this a real thing? Can it actually happen?” And she tells them that yes, if the plan goes as a growing number of people hope it will, it just might.

This story was produced with support from the Climate Equity Reporting Project at Berkeley Journalism.

A first-of-its-kind pilot to electrify homes on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard is set to finish construction in the coming weeks — and it could offer a blueprint for decarbonizing low- and moderate-income households in Massachusetts and beyond.

The Cape and Vineyard Electrification Offering is designed to be a turnkey program that makes it financially feasible and logistically approachable for households of all income levels to adopt solar panels, heat pumps, and batteries, and to realize the amplified benefits of using the resources together. These technologies slash emissions, reduce utility bills, and increase a home’s resilience during power outages, but are often only adopted by wealthier households due to their upfront cost.

“We are going to be advancing this as a model that should be emulated by other states across the country that are trying to achieve decarbonization goals,” said Todd Olinsky-Paul, senior project director for the Clean Energy Group, a nonprofit that produced a new report about the program.

In total, the program is providing free or heavily subsidized solar panels and heat pumps to 55 participating households, 12 of which also received batteries at no cost. Work should be completed on the final participating home this month.

“This is the first and only instance where solar and battery storage are being presented in combination with electrification and traditional efficiency,” Olinsky-Paul said. “Instead of having several siloed programs, it’s all being presented to the customer in a package, which makes everything work together better.”

It’s a strategy that program planners hope can help address the disproportionate energy burden felt by lower-income residents of the region, where households making less than one-third of the area median income spent an average of 27% of their income on energy as of 2023, according to data from the U.S. Department of Energy. (The updated figure is unavailable because the federal tool that provided this data is no longer live.)

The initiative is a project of the Cape Light Compact, a unique regional organization that negotiates electric supply prices and administers energy-efficiency programming for the 21 towns on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard. The compact first proposed the pilot in 2018, but regulators rejected the idea. The organization submitted a revised version in 2020 and 2021, but it wasn’t until 2023 that the state finally gave the program the green light.

An energy-efficiency contractor partners with each program participant to assess their home, then coordinates the necessary work, including any preparations that need to be completed before solar panels, heat pumps, or batteries can be put in. The batteries installed through the program are enrolled in ConnectedSolutions, a state program that pays battery owners who send power to the grid when needed. Because the pilot footed the bill for the batteries, these payments will go to the Cape Light Compact, rather than residents, to help defray the cost of the program.

Bringing the program to life was not always a smooth process. The original proposal called for 100 homes to participate in the pilot, but the final number fell well short of that target. Some homeowners who originally expressed interest were put off by the requirement to remove all fossil-fuel systems from their homes, particularly if they had recently invested in new gas or propane heating, said Stephen McCloskey, an analyst with the Cape Light Compact and the program manager for the pilot.

In some cases, homeowners balked at up-front costs. Moderate-income households that did not live in deed-restricted affordable housing had to pay 20% of the cost for heat pumps and any cost over $15,000 for solar panels. If a roof was too shady for solar, homeowners were responsible for removing trees and branches.

“At the end of the day, each customer and their decision-making process is different,” McCloskey said.

The original plan called for installing batteries in 25 participants’ homes, but unexpected limitations lowered that number, McCloskey said. Houses without basements, for example, couldn’t receive batteries. In some cases, the combined capacity of solar panels and a battery would have exceeded the local utility’s threshold for connecting a system to the grid.

The compact also had not fully accounted for the array of barriers that needed to be addressed before weatherization could be done. Some homes had mold or needed electrical upgrades. Others required roof work before solar panels could be installed.

These challenges are not dealbreakers but lessons learned for utilities or organizations that attempt to emulate the program in the future, McCloskey said. And Olinsky-Paul sees great potential for similar plans to be pursued nationwide. Nearly half of U.S. states have adopted 100% clean energy targets, he said, and distributed-energy programs like the Cape and Vineyard’s can make those goals more achievable by reducing the cost and strain electrification can create for the grid.

“If you’re going to do decarbonization, you have to do electrification,” Olinsky-Paul said. “And so there is going to be a huge need for some way of doing this without inadvertently causing massive new fossil-fuel use” to generate more power.

The Cape Light Compact intends to release a full report on the deployment of the pilot in August, but feedback so far has been very positive from participants who appreciate the turnkey approach to comprehensive electrification, McCloskey said.

“There are definitely things that whoever is facilitating that program would need to look at, to game plan for,” he said. “But this is a great model.”

Five years ago, San Francisco–based startup Span debuted a smartphone-controllable electrical panel that allows homeowners to manage their solar panels, backup batteries, EV chargers, HVAC systems, and other major household appliances in real time. It was a high-end product for a high-end market.

But as more households purchase EVs, heat pumps, induction stoves, and other power-hungry devices, the demand for cheaper ways to control their electricity use is growing — not just from homeowners trying to avoid expensive electrical upgrades but utilities struggling to keep up with rising power demand, too.

Enter the Span Edge, unveiled at the Distributech utility trade show in Dallas this week. The device packs the startup’s core technology into a package that can be installed in about 15 minutes and plugged into an adapter that connects to a utility electric meter.

Span’s other products are targeted at homeowners; electrical contractors; and solar, battery, and EV charging installers. But the Span Edge, which requires a utility worker to install, is “expanding way beyond a homeowner or installer-led adoption of the product, to becoming part of the utility infrastructure,” said CEO Arch Rao.

That makes it one of a growing number of tools for utilities to manage the solar, batteries, EVs, controllable appliances, and other distributed energy resources that they must increasingly plan around.

If utilities manage these resources reactively, they could drive up the cost and complexity of managing the grid. But if utilities can get better information about when and how these devices use power — and if some customers are willing to adjust them sometimes to reduce grid stress — they could actually save ratepayers a lot of money.

That’s what Span’s new technology aims to allow. The company’s “dynamic service rating” control scheme can throttle or shift power use between household electrical loads, based on a homeowner’s preset or real-time priorities. That helps ensure total draw on the utility grid stays below a home’s top electrical service capacity, which typically ranges between 100 and 200 amps.

Households that want to exceed the limit of their electrical panel are often forced to upgrade to a larger one. Depending on where you live, that can cost from $3,000 to $10,000 and add days to weeks of extra time to a project, like installing an EV charger. If a utility determines a home’s new maximum power draw will trigger grid upgrades, the project could be even more expensive and take much longer to complete. In the worst case, that could kill households’ plans to do everything from switching to an EV to electrifying their heating and cooking.

It’s also expensive for utilities. “Where consumers are adding heat pumps and EV chargers, the existing solution has always been, ‘Let’s build more infrastructure — more poles and wires — to meet the maximum load,’” Rao said.

Installing a device like the Span Edge could well be a more cost-effective alternative, not just for the customers who get one but for customers as a whole. Utility rates are largely determined by dividing the amount of money earned from electricity sales by the amount of money utilities have to collect from customers to cover their costs. A big and rising portion of U.S. utility costs is tied up in upgrading and maintaining their power grids, including to meet rising demand for power from EVs and heat pumps. As a result, ratepayers in many parts of the country are seeing higher bills.

If devices like the Span Edge can cut those grid costs while allowing people to buy more electricity for EVs and heating, rates for everyone will drop over time, Rao said. While some utilities may balk at replacing profitable grid-upgrade investments with new technology, others that want customers to electrify to meet carbon-reduction mandates or to increase electricity sales may be eager to implement it, he argued.

Span’s smart electrical panel was among the first attempts to give the old-fashioned electrical panel a 21st-century makeover.

But similar products that also embed circuit-level controls are now available from major manufacturers, including Schneider Electric and Eaton; startups such as Lumin and Koben; and solar and battery vendors like FranklinWH, Lunar Energy, and Savant.

Utilities have been experimenting with such technologies for a while. Some plug directly into utilities’ existing electric meters, including the Span Edge, ConnectDER’s smart meter collar devices, or the Tesla backup switch.

Others are embedded elsewhere in a home’s electrical system, like the controls product startup Lunar Energy is developing using Eaton’s smart circuit breakers. Those digital, wirelessly connected breakers are “modular, interoperable, and retrofittable,” Paul Ryan, the company’s general manager of connected solutions and EV charging, told Canary Media in October. That’s helpful “as you add heat pumps and electric vehicle charging,” he said — and could be useful for utilities, a group of customers Eaton has worked with for many years.

The trick for all of these technologies is to combine the convenience and simplicity consumers demand with utility safety and reliability requirements, said Scott Hinson, chief technology officer of Austin, Texas–based nonprofit research organization Pecan Street.

In a 2021 report, Pecan Street estimated that about 48 million U.S. single-family homes with service below 200 amps might need to upgrade their electrical panels to support electric heating, cooking, and EV charging.

But not all of the technologies that allow customers and utilities to sidestep upgrades necessarily meet the needs of both parties, he said.

Take the smart-home platforms on offer from Amazon, Apple, Google, Samsung, and other tech vendors, which can control light bulbs, thermostats, ovens, refrigerators, and a growing roster of other devices. These systems rely on WiFi and broadband connections, and that’s not good enough to let households skip upgrading their electrical panels, Rao pointed out. The latest certifications for power control systems require fail-safes that work even when the internet is down, something Span’s products do by sensing overloads and shutting down circuits.

On the other hand, rudimentary on-off control switches are far from ideal, Hinson said.

“A lot of these devices don’t like to be controlled” by having their power cut off externally in such a rough-and-ready manner, he added. For example, abrupt power cutoffs trigger the “charging cord theft alert” feature in EVs like the Chevy Volt, which starts the car alarm until the owner shuts it off — not a pleasant experience for the EV owner or neighbors.

More importantly, Hinson said, a good system needs to control “large loads so they’re aware of each other,” he said. Homeowners want to control which appliances get shut off when the need arises, whether it’s their EV charger, clothes dryer, oven, or heating and cooling, he said. But to do that, “the car has to know what the electric oven is doing, which has to know what the heater is doing.”

Span’s devices have two ways to do this, Rao said. Because they contain the connection points for power to flow through circuit breakers to a home’s electrical wiring, the devices can directly measure how much power household loads are using — and cut them off completely in an emergency.

At the same time, Span uses WiFi or other technologies to communicate with “smart” heat pumps, water heaters, EV chargers, and other devices, he said. That allows households to control the power that devices get on a more granular scale as well as collect information beyond how much power they’re using, such as when an appliance is scheduled to turn back on or, for EVs, how quickly they need to be recharged to give the driver the juice they need to get to where they’re going next.

What’s important is that a system can provide both options, Rao contended. “If you only did on-off control, the customer experience is bad,” he said. “If you only did WiFi, you’re not safe enough for the grid.”

Having both visibility into and control over home electricity flows creates the groundwork for a more flexible approach to enlisting homes in utility virtual power plants, or VPPs. In simple terms, VPPs are aggregations of homes and businesses that agree to turn down power use or inject power onto the grid as utilities need, helping reduce reliance on large centralized power plants.

Most of the virtual power plants that exist today are organized around individual devices — smart thermostats that can reduce electricity demand from air conditioning, for example, or solar-battery systems that can send power back to the grid. Each of these technologies has its limitations, and utilities’ reliance on them is often constrained by a lack of precise data on how much power the grid is using or can offer at any particular time.

A system that tracks the energy use of multiple appliances and devices in a home could bring far more precision to these VPPs, Rao said. “That’s very different than the demand-response world, where you call a thermostat and say ‘I hope it responds to me.’”

Utilities certainly have a growing interest in using these kinds of devices. On Monday, Pacific Gas & Electric announced a new VPP pilot program that seeks to enlist customers willing to allow the utility to control their “residential distributed energy resources to reduce local grid constraints.”

PG&E is looking for up to 1,500 electric residential customers with battery energy storage systems and up to 400 customers with smart electric panels. Its partners include leading U.S. residential solar and battery installer Sunrun, which has done VPP pilots with the utility in the past, and Span, which will use its technology to allow homes to respond to utility signals.

Span has already tested this capability in a pilot project enlisting customers who’ve installed the company’s smart panels in Northern California, Rao said. The results so far are promising, although only a handful of households are taking part.

Getting utilities to deploy Span Edge devices could expand the scale of those kinds of programs, he said. Of course, households will have to agree that letting some of their electricity use get turned off or dialed down during hours of peak grid stress is worth avoiding the cost and wait times of upgrading their electrical service to get the EV charger or heat pump they want.

Span hasn’t revealed the cost of the Span Edge, which Rao said will soon be deployed in pilot projects with as-yet unnamed utilities. The company has a partnership with major smart-meter vendor Landis+Gyr, which is offering the Span Edge to its utility customers.

The question for utilities, regulators, and other stakeholders is whether the long-term payoff in avoided infrastructure upgrades is worth the cost of the technologies that must be deployed to make that possible. Those calculations will inform decisions such as whether customers getting the technologies should pay a portion of the price tag and how much profit utilities should be allowed to earn on the costs they bear in installing the tech.

PG&E’s chief grid architect, Christopher Moris, said the Span Edge device “is a potential solution which may be able to, at a reduced cost, enable customers to connect their EV and transition off of gas.” One of the utility’s biggest near-term challenges is helping customers install EV chargers, he noted. PG&E has more than 600,000 EVs in its service territory, almost certainly more than any other U.S. utility.

The company also faces customer and political backlash to its recent rate hikes, a problem driven by its need to carry out more and costlier power grid upgrades. While devices like the Span Edge could help address that problem, “we realize how new such a concept is for our customers,” Moris said.

“I’m very bullish on this new solution — but we don’t know what we don’t know,” he said. PG&E “will need to go through a customer discovery process to really understand their challenges more first, before definitely landing on the Span solution and, if so, what the end-to-end solution looks like.”

A clarification was made on March 26, 2025: An earlier version of this article implied that Lunar Energy and Eaton are co-developing a home energy controls product, and that Eaton is testing its AbleEdge circuit breakers for use by utilities. In fact, Lunar Energy is integrating Eaton’s AbleEdge smart breakers into Lunar Energy’s home energy controls platform, and while Eaton has worked with utilities in the past, it has yet to test its AbleEdge devices with utilities.

This story originally appeared in New York Focus, a nonprofit news publication investigating power in New York. Sign up for their newsletter here.

New York state is one step closer to banning fossil fuels in new buildings.

On Friday, the State Fire Prevention and Building Code Council voted to recommend major updates to the state’s building code, which is updated every five years and sets minimum standards for construction statewide. The draft updates include rules requiring most new buildings to be all-electric starting in 2026, as mandated by a law passed two years ago.

The vote came after the code council went missing in action for more than two months, leaving some advocates nervous that the state might be wavering on the gas ban. With the rules now entering the final stage of the approval process, New York remains on track to be the first state to enact such a ban.

The new draft code also tightens a slew of other standards in a bid to make buildings more energy efficient and save residents money over the long term. But it leaves out several key provisions recommended in the state’s climate plan — possibly running afoul of a 2022 law.

Specifically, the draft energy code leaves out requirements that new homes include on-site energy storage and be wired such that owners can easily add electric vehicle chargers (when the property includes parking space) and solar panels. The state’s 2022 climate plan listed these three provisions as “key strategies” to achieve New York’s legally binding emissions targets. On-site energy storage also makes homes more resilient when disasters strike, the plan noted, providing backup power in the event of a blackout.

A separate 2022 law required the state to take those recommendations into account when updating its building code.

“Updating the infrastructure for those things is a key part of what this transition is,” said Michael Hernandez, New York policy director at the pro-electrification group Rewiring America.

The Department of State, which oversees New York’s code development process, did not respond to a request for comment.

Buildings are New York’s largest source of emissions, according to the state’s accounting, amounting to nearly one-third of all climate pollution. New York’s buildings burn more fossil fuels for heat and hot water than any other state’s, according to the clean-energy group RMI. That contributes not only to global warming but also to local air pollution, with deadly consequences: A 2021 study by Harvard researchers found that pollution from New York’s buildings causes nearly 2,000 premature deaths a year.

Cutting that pollution will require major upgrades to the state’s aging housing stock — an enormous challenge. But climate hawks stress that the first and easiest step is to stop digging the hole deeper, by making new buildings as climate-friendly as possible. Making them all-electric is a key part of that. But other, subtler changes can also play an important role.

The fossil-fuel industry, for its part, is taking those changes seriously. Gas trade groups led a major fight to keep provisions such as the EV-ready requirement out of the national building code that provides a model for states including New York. After nearly five years of wrangling, the International Code Council — actually a national nonprofit — that oversees the process voted not to include the provisions as requirements, siding with the gas groups over the advice of its own experts.

Among the parties who stood up for the stricter energy code: a New York state code official, who joined advocates like Hernandez one year ago in urging the International Code Council to keep the requirements in. Yet the state is now following the national group’s lead and relegating the solar, electric vehicle, and battery standards to the appendices of its draft code. That means they can still serve as templates for localities that want to adopt the tougher standards, but they’re not required.

Fossil-fuel interests and some Republican lawmakers have argued that including such mandates would only drive up the cost of new homes at a time when housing is already deeply unaffordable. But climate advocates point out that it’s far cheaper to install electrical infrastructure up front than add it in later on — as much as six times cheaper in the case of an EV charger, for example.

That’s in keeping with many of the green rules that New York did include in its new draft code. Chris Corcoran, a code expert at the state energy authority NYSERDA, told the code council on Friday that adopting the full suite of proposed energy rules will add about $2 per square foot to the up-front cost of new homes but save residents more than three times that over 30 years.

It’s not entirely clear who in New York has pushed to leave the storage, solar, and EV provisions out. Only eight groups disclosed that they lobbied on the building and energy codes last year, and it’s not obvious that any of them had a specific interest in opposing those rules.

Officials speaking at Friday’s meeting did not explain why they left out the requirements. One lawyer who helped draft the updated energy rules, Ben Kosinski, left the Department of State just this month to work as chief counsel for the Senate Republicans, for whom he also worked before joining the code office, according to his LinkedIn profile. The GOP caucus has voted almost unanimously against the laws driving the pro-electrification updates to the code. (Kosinski did not immediately reply to a request for comment.)

Although the council voted unanimously on Friday to advance the all-electric rules, not all members supported the move. William Tuyn, a builders’ representative from the Buffalo area, noted that the state adds roughly 40,000 homes a year — a tiny fraction of the roughly 7 million that already exist.

“We don’t even make a dent in the issue of climate change by focusing there,” he said in the final minutes of the meeting. “The Legislature did what they did. That ship has sailed … [but] we really need to concentrate on renewables or improving the grid if we’re really going to be able to do something and we’re not just going to simply crash the economy of the state of New York.”

Several lawmakers urged the council on Friday to include the full suite of climate provisions in the final rules.

“These provisions are not trivial add-ons. They are the backbone of a truly effective energy code,” said Neil Jimenez, legislative director for Assemblymember Yudelka Tapia. “Their exclusion weakens the very foundation upon the policies we’ve fought so hard to put into place here in Albany.”