OIL & GAS: A federal judge orders BNSF Railway to pay nearly $400 million to the Swinomish Tribe for violating an easement agreement by repeatedly running 100-car oil trains across its land in Washington state. (Associated Press)

ELECTRIC VEHICLES:

TRANSPORTATION: Colorado regulators find a Denver-area transit agency failed to address escalating light rail maintenance problems that have slowed trains and stymied service. (CPR)

CLEAN ENERGY:

SOLAR:

ELECTRIFICATION: A California startup develops software aimed at helping people cost-effectively pair home electrification and rooftop solar. (Canary Media)

UTILITIES:

CLIMATE: Conservation groups call on the Biden administration to define extreme heat and wildfire smoke as major disasters and unlock relief funding for affected local governments. (Los Angeles Times)

NUCLEAR: Federal regulators seek public input on a Bill Gates-backed plan to build an advanced nuclear reactor in a Wyoming coal community. (WyoFile)

MINING: State and federal regulators approve a uranium mining firm’s proposed exploratory drilling project in western Colorado. (Resource World)

Massachusetts environmental justice advocates say the $5 billion statewide energy efficiency plan that could take effect next year needs to do even more to reach low-income residents, renters, and other populations who have traditionally received fewer benefits.

The plan, which will guide efficiency programming from 2025 through 2027, outlines wide-ranging initiatives that would support weatherization and heat pumps for homes and small businesses, improve the customer experience with more timely rebate processing and increased multilingual support, and expand the energy efficiency workforce. The proposed plan calls out equity as a major priority.

“There have certainly been some changes in this latest draft we’re pleased to see, but there is definitely a lot more that needs to be done, especially in the realms of equity and affordability and justice,” said Priya Gandbhir, senior attorney at the Conservation Law Foundation. “The good news is we’re still working on this, so there’s some time for improvement.”

Massachusetts has long been considered a leader in energy efficiency, ranking at or near the top of the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy’s annual State Energy Efficiency Scorecard for more than 10 years. The core of the state’s efficiency efforts is Mass Save, a partnership between gas and electric utilities, created in 2008, that provides education, energy audits, rebates on efficient appliances, low and no-cost weatherization services, and financing for efficiency projects.

Mass Save programming is guided by the three-year energy efficiency plans put forth by the major utilities in collaboration with the state Energy Efficiency Advisory Council, and approved by state public utilities regulators. Over the past several years, legislation has required that Mass Save prioritize reducing greenhouse gas emissions, rather than focusing only on using less energy.

“Mass Save needs to be a tool not just for energy efficiency but also for decarbonization,” said Hessann Farooqi, executive director of the Boston Climate Action Network.

In recent years, there has also been an effort to ensure the benefits of Mass Save programs are distributed equitably. A 2020 study by the utilities found that communities with lower incomes, higher proportions of residents of color, and more renters were far less likely to have used Mass Save services.

Following this report, the three-year plan covering 2022 to 2024 included several provisions intended to address these disparities, including a 50% higher budget for income-eligible services, financial incentives for utilities to serve lower-income households, and grants to community organizations that can help connect residents to information about Mass Save benefits.

The plan’s focus on equity was hailed by advocates.

“We’ve seen a dramatic increase in production and service and savings because of the increased budget,” said Brian Beote, an Energy Efficiency Advisory Council member and director of energy efficiency operations for housing security nonprofit Action Inc. “We’ve been able to bring on more contractors and serve more households.”

This latest plan continues the focus on equity for underserved populations in several ways. The draft plan increases the budget for services to income-eligible households, defined as those with incomes below 80% of the area median, from roughly $600 million to nearly $1 billion, the highest number ever proposed.

The draft plan also attempts to simplify the process of obtaining benefits for residents in areas that have been marginalized in the past. The plan identifies 21 “equity communities” – municipalities in which more than 35% of residents are renters and more than half of households qualify as low or moderate income. Residents in these communities would be eligible for no-cost weatherization and electrification, often without income verification, and rental properties would be able to receive low-cost weatherization and electrification services.

This approach might mean higher-income customers receive no-cost services they might otherwise have had to pay for, but supporters say the likely benefits outweigh this possibility.

“On balance, we’re going to get more of those low- to moderate-income customers and that is really a key goal,” Farooqi said.

In addition, the proposed plan would expand the Community First Partnership program, which provides funding to nonprofits and municipalities to target outreach and education about Mass Save’s offerings, using their knowledge of their communities and populations.

Still, the plan misses several opportunities to make even greater strides toward equity, advocates said. At the heart of their argument are funding levels: The budget for low- and moderate-income services is about 19% of the total budget, even as nearly half of the state’s households fall into that category.

“We just need to be making sure that we are distributing the benefits of this program proportionally to where people are actually at in the population,” Farooqi said.

The plan’s targets for heat pump installations are another point of contention. The plan calls for installing 115,000 heat pumps during the plan period, with 16,000 of these going to low- and moderate-income households. This target is not nearly high enough, advocates said.

“That’s a major failure,” said Mary Wambui-Ekop, an energy justice activist and co-chair of the Energy Efficiency Advisory Committee’s equity working group. “They definitely need to increase that target to 30,000, and even that is really low.”

Switching from gas heating to heat pumps at current high electricity rates could increase costs for customers, so it is also important that the push to electrify heating for lower-income residents focus on households currently using higher-emissions, higher-cost fuels like heating oil or propane, Wambui-Ekop said.

In Massachusetts, some 800,000 households use heating oil and propane; more than 151,000 of these households fall within the plan’s designated equity communities.

“If they switch to heat pumps, they will see their energy bills go down, their energy burdens will go down, they will have good indoor air quality, and the commonwealth will benefit because of the greenhouse gas reductions,” Wambui-Ekop said.

Advocates are also waiting to see the details for the plans to expand the Community First Partnership program. At current levels, the funding can pay a part-time energy staffer at a modest rate, which can make it difficult to find and keep qualified employees, said Susan Olshuff, a town liaison with Ener-G-Save, a Community First Partner organization in western Massachusetts. She’s gone through six different staffers since the program began and is anxiously waiting to see the final funding that comes out of the new plan.

“I like to think it will be enough,” she said, “but I am nervous to see what numbers they come down on.”

The final plan will be submitted to the state in October. Public utilities regulators will then be able to approve the plan as a whole, or to suggest modifications. Advocates are hoping to see an even more equitable plan filed and approved.

“The people who can afford to do it will do it on their own,” Gandbhir said. “We need to make sure that people who are renting or who aren’t able to afford the upfront costs are provided with the assistance that’s needed.”

OIL & GAS: A New Mexico court rejects an industry request to toss out an environmentalists’ lawsuit accusing the state of failing to meet its constitutional obligation to protect citizens from oil and gas pollution. (Associated Press)

ALSO: Environmentalists sue to block federal Bureau of Land Management oil and gas drilling permit approvals in and around an eastern Colorado national grassland, saying the agency didn’t adequately consider impacts. (news release)

CLIMATE:

GRID: Amazon scraps a plan to power its eastern Oregon data centers with natural gas-powered fuel cells after advocates protest its reliance on methane. (Oregonian)

NUCLEAR: Bill Gates attends his company’s liquid sodium testing facility groundbreaking ceremony at the site of an advanced nuclear reactor planned for a Wyoming coal community. (WyoFile)

OVERSIGHT: Arizona advocates push back on a company’s bid to exempt its proposed 200 MW natural gas plant expansion from environmental review, saying it would undermine regulators’ oversight. (KJZZ)

UTILITIES: San Diego’s city council votes to reject a bid that would allow voters to decide whether to replace SDG&E with a municipal utility. (KUSI)

SOLAR:

SYNTHETIC FUELS: A Nevada startup working to convert solid landfill waste into synthetic petroleum lays off most of its staff and shutters its Reno facility following permitting and operational setbacks. (Chemical & Engineering News)

HYDROGEN: An Oregon startup says it has successfully produced green hydrogen using power from a wind turbine mounted on a ship. (Power)

COAL: Utah energy experts predict lawmakers’ push to block federal regulations and keep coal plants running may hamper energy innovation and ultimately lead to more expensive, dirtier and less reliable power generation. (Utah News Dispatch)

MINING: Nevada environmental and Indigenous advocates slam the federal Bureau of Land Management’s review of the proposed Rhyolite Ridge lithium-boron mine, saying it imperils endangered species and fails to include a groundwater mitigation plan. (Nevada Current)

METHANE: Washington state implements rules aimed at reducing solid waste landfills’ methane emissions by requiring them to monitor and repair leaks and install equipment to capture the potent greenhouse gas. (Washington State Standard)

COMMENTARY: An Indigenous advocate calls on the federal Bureau of Land Management to avoid perpetuating energy injustice by engaging with tribal nations as it develops its new Western solar plan. (Santa Fe New Mexican)

This story was originally published by Canary Media.

Over the past three years, an unusually broad coalition has come together to champion a new way to finance and build community-solar-and-battery projects in California. It includes solar companies, environmental justice activists, consumer advocates, labor unions, farmers, homebuilder industry groups, and both Democratic and Republican state lawmakers — a rare instance of concord in a state riven by conflicts over rooftop solar and utility policy.

Supporters say the plan, known as the Net Value Billing Tariff, could enable the building of up to 8 gigawatts of community-solar-battery projects over the coming decades, all of which would be connected to low-voltage power grids that sell low-cost power to subscribing households, businesses, and organizations.

But on Thursday, the California Public Utilities Commission voted 3–1 to reject the coalition’s plan. Instead, it ordered the state’s major utilities — Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric — to restructure a number of long-running distributed solar programs that have failed to spur almost any projects in the decade or more they’ve been in place.

Critics warn that these utility-backed plans won’t create a workable pathway to expanding a class of solar power that has become a major driver of clean energy growth in other states and a key focus of the Biden administration’s energy equity policy.

They also fear that the CPUC’s reliance on state and federal subsidies to boost the economic competitiveness of these existing failed community-solar models might jeopardize the state’s ability to even qualify for the $250 million in community-solar funding that the Biden administration has provisionally offered it.

“We are cheating ourselves out of the benefits of community solar and storage with this decision,” said Derek Chernow, western regional director for the Coalition for Community Solar Access (CCSA), which represents companies and nonprofits that advocate for community solar.

Since CCSA devised the NVBT in 2021, it has won “unprecedented bipartisan broad-based support from stakeholders that don’t typically come together and see eye to eye on clean energy issues,” Chernow said.

The plan the CPUC cobbled together from utility proposals, by contrast, lacks “any support — broad-based or otherwise,” he said.

CPUC President Alice Busching Reynolds defended the decision to reject the NVBT at Thursday’s meeting. She pointed to other existing California programs that assist low-income households and multifamily buildings in obtaining solar, and noted that the CPUC’s plan will expand an existing community-solar program that offers low-income customers a 20 percent reduction on their bills.

She said that the NVBT program was too costly a way to bring new solar-and-battery resources to the state, compared to the large-scale energy projects being contracted by utilities and community energy providers.

“California is really at an inflection point where we must use the most cost-effective clean energy resources that provide reliability value to the system,” Reynolds said.

Backers of the NVBT hold a very different view. Since March, when the CPUC unveiled its proposed decision to reject the NVBT, there has been broad public outcry. Letters protesting its proposal have flooded into the CPUC from community-solar advocacy groups, environmental organizations, commercial real estate companies, farmworker advocacy groups, farming industry associations, and Republican and Democratic state lawmakers.

The CPUC issued a revised proposed decision on Tuesday, ahead of Thursday’s vote, which differed little from the initial March proposal. The only major change was the removal of a legal argument claiming that the NVBT violates federal law — a theory that was met with widespread incredulity and was rebutted by three former chairs of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in letters to the CPUC.

The Utility Reform Network (TURN), a nonprofit that advocates for utility customers, has warned that the CPUC’s community-solar plan will “favor large utility companies by ensuring solar program development costs are incurred by home builders, renters, and other solar community participants,” while failing to offer lower-income customers a chance to reduce their fast-rising electric bills by subscribing to lower-cost solar power.

And 20 lawmakers who supported AB 2316, the 2022 state law that ordered the CPUC to create an equitable and affordable community-solar program, have told the CPUC that its failure to support the NVBT could mean the state falls short on its clean energy and climate goals.

“Transmission-scale renewables face significant siting, interconnection, and transmission challenges,” creating the risk that utilities won’t be able to hit the aggressive clean energy procurement targets set by the CPUC, the lawmakers wrote in a September letter. “Small, distribution-sited community solar and storage projects have incredible potential as we modernize and expand our transmission system.”

Speaking at Thursday’s CPUC meeting, Assemblymember Chris Ward, the San Diego Democrat who authored AB 2316, called the CPUC’s pending decision “a dismissal of California’s need for clean, reliable, and affordable energy.”

“After agreeing with nearly all stakeholders that the state’s existing community renewables programs are not workable, the proposed decision has opted to repeat these mistakes by creating an outdated, commercially unworkable program that will result in no new renewable energy projects or energy storage,” he told the CPUC commissioners, all of whom were appointed by Governor Gavin Newsom (D).

California leads the country in rooftop solar and stands behind only Texas in utility-scale solar-and-battery farms. But its community-solar projects make up less than 1 percent of the 6.2 gigawatts of community solar that have been built in the 22 states with policies that support this form of solar development. That’s largely because the community-solar programs that have existed in California for more than a decade have been unattractive to solar developers, financiers, and would-be subscribers.

The earliest programs, which targeted commercial and industrial customers, charged a premium over standard utility rates, making them undesirable. Later programs created for lower-income and disadvantaged communities have been stymied by limits on how many megawatts’ worth of projects can be built and the size of individual projects, as well as onerous rules that require projects serving disadvantaged communities to be located within five miles of those customers.

Designed to remove those barriers, the NVBT was modeled on a community-solar program created by New York that has led to more than 2 gigawatts of projects in that state. That structure allows community-solar projects to earn steady revenues from the power they produce based on a complex calculation of benefits. Those benefits include helping to meet state climate goals, bringing clean power to underserved customers, and, importantly, helping to support utility grids by, for example, avoiding the cost of securing power during the rare hours of the year when utility grids face the greatest stress.

Unlike California’s existing community-solar programs, the NVBT would incentivize projects to add batteries to store and shift solar power from when it’s in surplus to when it’s most needed on the grid.

And under AB 2316, any new community-solar-and-battery projects in California must provide at least 51 percent of their capacity to serve low-income residential customers at prices that reduce their electricity bills — a valuable option for low-income households, renters, and other utility customers that can’t access rooftop solar.

“We’re very interested in seeing renters have access to community-solar projects,” said Matt Freedman, a staff attorney at TURN. “And we’re excited that the California statute requires at least 51 percent of the benefits go to low-income customers. We think that’s revolutionary — that we’re putting low-income customers first in line to receive the benefits of these projects.”

To date, California’s community-solar programs have subsidized lower-income customers through funds drawn from utility ratepayers at large or from the state’s greenhouse gas cap-and-trade program. NVBT backers hoped the structure they proposed would allow projects to earn enough money in their own right to support reduced rates for lower-income customers.

But all the revenues and benefits of community-solar-battery projects under the NVBT rely on a common factor, Freedman said: being able to tap into the same value structure that dictates what rooftop-solar-equipped customers served by California’s three major utilities earn for their solar power. That structure is called the avoided-cost calculator, and AB 2316 explicitly cited it as the metric that the CPUC should use to determine the value of community solar, he said.

The CPUC’s decision rejected that reading of the law, however. Instead, it agreed with the state’s big utilities that the solar-and-battery projects that the NVBT would finance could increase costs on some of the state’s utility customers in excess of the value those projects would provide to customers at large.

To reach that conclusion, the CPUC didn’t compare the cost and value of community-solar-and-battery projects against the value assigned to rooftop solar systems and other distribution-grid-connected clean energy resources. Instead, it compared their value against wholesale “avoided-cost” rates of electricity generated by power plants, utility-scale solar-and-battery farms, and other large-scale resources.

Those resources provide power that’s much cheaper on a per-kilowatt-hour basis than power from community-solar-battery projects, which face higher land and construction costs connected to building in more populous areas, and which can’t match the economies of scale achieved by solar-and-battery farms in the hundreds of megawatts apiece.

But by choosing that comparison point, the CPUC also dismissed the value that distributed community-solar projects can provide by delivering power much closer to customers than far-off power plants and solar farms connected by expensive high-voltage transmission lines, Freedman said.

A better comparison, he suggested, would be against a form of solar-and-battery power that community projects could actually supplant to significant economic benefit — the solar systems all new homes and many new commercial and multifamily buildings must include under California building codes.

That’s why the California Building Industries Association trade group has been a strong supporter of the NVBT. CBIA estimates that the state’s building codes will require the addition of 250 to 400 megawatts of new solar per year over the coming decade to keep up with the pace of residential construction. Community solar and batteries under the NVBT could be a much cheaper way to meet those requirements — but only if developers have a program that makes building those projects economically viable.

It’s hard to see how the CPUC’s newly enacted Community Renewable Energy Program (CREP) structure will make that possible.

In essence, the CPUC has ordered utilities to restructure two existing tariffs that allow distributed energy projects to sell their power to utilities at wholesale avoided-cost rates: the Renewable Market Adjusting Tariff (ReMAT) program, which allows projects of up to 3 megawatts, and the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) Standard Offer Contract, which allows projects of up to 20 megawatts.

But the low prices and short contract terms for these structures have been extremely unattractive to clean energy developers. No project has been completed under the “standard offer contract” structure since 1995, and only one 3-megawatt solar-only project has been built under ReMAT since 2021, Freedman said.

It’s hard to envision lenders or investors backing a solar project with such an unclear pathway to profitability, CCSA’s Chernow said. What’s more, neither of those tariffs reward projects that invest in batteries to store solar power when it’s not as valuable for the grid and discharge it during times of grid stress, he said.

“You don’t get the scalability, you don’t get the growth, you don’t get the storage — you don’t get all of the avoided-cost benefits that were originally set up with the Net Value Billing Tariff,” he said.

To make matters worse, both of those programs are meant to supply lower-income customers with solar power that can reduce their electricity bills, Freedman said. But retail electricity rates in California are five to six times higher than the wholesale rates that the CPUC would allow these projects to earn.

To make up for that discrepancy, the CPUC has ordered utilities to use “external funding or incentives” to offer credits to subscribing customers that are structured in a way that doesn’t increase their utility energy costs. Low-income customers, which must make up at least half of all subscribers, “will receive no less than 20 percent” bill credits.

But at present, the only money the CPUC has identified for these external sources is $33 million in state-approved funding available for community-solar usage and storage-backed renewable-generation programs. Beyond that, Thursday’s decision orders utilities to look to federal investment tax credits and a set of programs created by the Inflation Reduction Act to spur investment and lending in underserved communities, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s $7 billion Solar for All program.

Last month, EPA announced 60 provisional recipients of that funding. California is set to receive $249 million, pending approval of how it plans to spend the money — including a commitment to ensure that low-income customers who participate will be able to lower their electricity bills by at least 20 percent compared to what they were paying before.

CPUC President Reynolds noted at Thursday’s meeting that “while we’re still waiting for guidance from U.S. EPA, we hope to use a significant portion of this funding to support projects and subscribers in this new program.”

But NVBT advocates say it’s far from clear that the programs that will evolve from the CPUC’s decision will provide the underlying utility tariff structures that could allow that federal funding to jump-start a commercially viable community-solar market. In fact, CCSA has calculated that the $249 million in federal funding would allow only about 50 megawatts of community-solar-and-battery projects to achieve economic viability under the CPUC’s proposal and still achieve the Solar for All program’s low-income energy-cost reduction targets, Chernow said.

That’s a far cry from the gigawatts of solar-and-battery projects financed and built by independent developers on a cost-effective basis that the NVBT could have incentivized to be built. But Freedman pointed out that even that relatively small-scale expansion might not be possible if developers decline to participate due to lack of clear long-term economics.

“Even if the state gets the commitment from the money, will we be able to spend it? If you design a program that developers don’t subscribe to, and there are no resources under the program, there’s no draw on the program,” he said.

CPUC Commissioner Darcie Houck, who voted against the decision, echoed some of these concerns at Thursday’s meeting. “The reliance on funding that may or may not be available in the future puts the program either at risk of failing or potentially having to have ratepayers cover the full cost of the program going forward,” she said. Houck was outvoted by commissioners John Reynolds and Karen Douglas and CPUC President Reynolds, with commissioner Matt Baker recusing himself.

Chernow said the CCSA planned to “work within the CPUC’s process to try to fix this as much as we can.” But without significant changes, he warned that the structure set by Thursday’s order stood little chance of spurring the kind of community-solar growth happening in other states.

The U.S. Department of Energy has set a goal of building 25 gigawatts of community solar by 2025, a fivefold increase from today. But Chernow fears the country as a whole “can’t get to these federal goals without California — and California can’t get there with this proposed decision.”

A $156 million federal grant is expected to fund a transformative investment in residential solar for low-income households in Massachusetts, advocates and officials say.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Solar for All program awarded Massachusetts the money for its plans to provide zero-interest loans, financial subsidies, and technical assistance to solar projects benefiting low-income households and public housing facilities. The state’s proposal was largely designed to take advantage of existing programs and resources to maximize the impact of federal funding.

The grant is the largest any New England state received from the program, but well below the $250 million Massachusetts requested. Still, the state expects to go ahead with all the initiatives outlined in its application, though planners are now working to reallocate money across intended programs to maximize impact.

“We were shooting for the stars,” said Elizabeth Mahony, commissioner of the state Department of Energy Resources. “This was an extremely competitive award process.”

Solar for All is a $7 billion program created in 2022 by the Inflation Reduction Act, an economic stimulus bill that included $369 billion in spending on energy and climate change programs. Solar for All will give grants to states, territories, nonprofits, tribal governments, and municipalities to increase solar development with the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, creating energy savings for overburdened households, and building markets for renewable energy businesses. The grants will target low-income and other marginalized communities where renewable energy has historically been less accessible.

Last month, the EPA announced the selection of 60 applicants for grants ranging from $25 million to $250 million. Only five grantees received larger awards than Massachusetts; 22 received the same amount.

Massachusetts’ proposal is structured around initiatives in three program areas: small residential buildings, multi-family housing, and community solar. The programs will be administered by a coalition of agencies including the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, the Boston Housing Authority, and MassHousing.

“They got a really strong coalition of major players involved,” said Kyle Murray, Massachusetts program director for climate nonprofit the Acadia Center. “While it’s disappointing that we did not get the full award, I cannot stress enough how much this money is going to be a game-changer for getting solar to low-income and disadvantaged communities.”

The small residential portion of the programming — originally slated to receive $40 million — includes two main initiatives. The first would provide low-income households with zero-interest loans to pay for solar panels. The program would be modeled after the MassSave Heat Loan program and the Mass Solar Loan, which sunsetted in 2020, having made some 3,000 loans to low-income borrowers for the installation of solar panels.

“We’re going back to that and reviving it because it was quite successful,” Mahony said.

The initial proposal also allocated $65 million to programs that would install solar panels on affordable housing and public housing, with the benefits flowing to the residents. In housing developments where tenants pay for their own utilities, they would receive savings from lower electricity bills. In housing where utilities are included in the rent, that benefit could be something other than energy bill savings: free wi-fi or improved facilities, for example.

Another provision of the Inflation Reduction Act will further amplify the financial power of installing solar panels on public and affordable housing. In the past, nonprofits were not eligible to receive clean energy tax credits because they paid no taxes. Now, clean energy tax credits are available to nonprofits in the form of a direct payment.

“It means we can then bring more federal resources into the state of Massachusetts,” said Joel Wool, deputy administrator for sustainability and capital transformation for the Boston Housing Authority, which will be administering the public housing portions of the grant programming statewide. “Every dollar that we can save on operating costs in public housing is a dollar we can put into making housing better.”

The community solar segment of the plan builds upon the state’s existing Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target, or SMART, program. All community solar projects receiving grant money will have to meet SMART’s existing requirement that at least half of the project’s offtakers are low-income residential customers. Additional points will be given to projects that offer deeper savings, serve a higher percentage of low-income households, or have members — such as nonprofits or affordable housing facilities — that benefit the community.

At the same time, the state is in the process of updating SMART to meet current environmental and economic needs. The Solar for All community solar program is likely to be tightly interwoven with these changes, Mahony said.

“We’re really leaning in hard on SMART when it comes to community shared solar that serves low-income customers in a way we never have before,” she said.

Smaller pools of money in the original plan were to be used to fund upgrades — such as roof replacements or wiring updates — needed to prepare buildings for solar panels, and to provide outreach and community engagement, workforce development, and technical assistance.

In addition to the environmental benefits and the savings for low-income residents, backers of the plan expect the influx of funds to have a long-term effect on the growth and stability of all facets of the renewable energy industry.

“That really enables the commonwealth and surrounding states to make those investments in their workforce and their supply chain, knowing that there will be demand for that equipment and those services in the years ahead,” said Maggie Super Church, director of policies and programs for the Massachusetts Community Climate Bank, a part of MassHousing.

The state is now in the midst of negotiating the final grant contract with the EPA, a process it expects to conclude this spring. The goal is to start rolling out the first programs in the fall.

“The numbers are still striking for what we can do,” Mahony said. “It’s just going to look a little different than how we laid it out in the first place.”

SOLAR: Multiple states are developing plans to address workforce shortages ahead of billions of dollars of federal investment in solar power. (Bloomberg)

ALSO: Puerto Rico’s rooftop solar boom is in jeopardy as a territorial agency weighs repeal of a new law extending net metering policies. (Canary Media)

CLIMATE:

UTILITIES: Energy justice advocates say Minnesota regulators should reinstate a moratorium on utility shutoffs after researchers found racial disparities in disconnections by Xcel Energy, even after accounting for income and other factors. (Energy News Network)

ELECTRIC VEHICLES:

GRID:

OIL & GAS:

WIND: Eight New Jersey towns have filed lawsuits in the past week to stop offshore wind development along the state’s coast. (Asbury Park Press)

A coalition of energy equity and justice advocates says Minnesota regulators should consider reinstating a utility shutoff moratorium after a recent academic study revealed racial disparities in disconnections by the state’s largest utility.

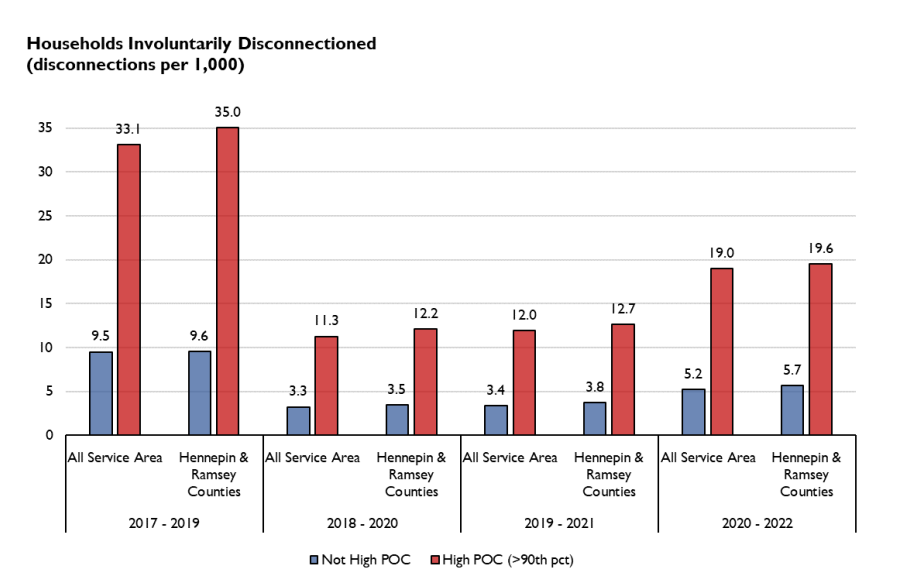

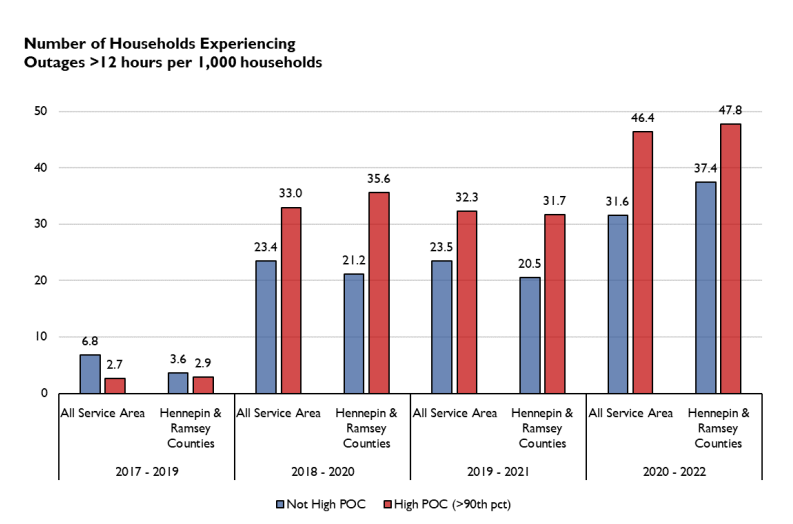

Xcel Energy customers in communities of color were more than three times as likely to have their electricity involuntarily disconnected between 2017 and 2021 compared to those in predominantly White neighborhoods, according to the analysis by the University of Minnesota’s Center for Science, Technology and Environmental Policy.

Those racial disparities persisted even after researchers controlled for other factors such as income, ownership status and housing age.

“We still find consistently that homes that are disconnected are predominantly” in communities of color, said Bhavin Pradhan, a postdoctoral associate and study co-author.

The study’s findings are at at the center of recent comments filed by advocacy groups including the Cooperative Energy Futures, Environmental Law & Policy Center, Sierra Club, and Vote Solar, which asked the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission last month to order a study of the costs and benefits of reinstating the state’s pandemic-era moratorium on utility shutoffs.

“(We) recommend that the Commission order this study now and then rely on it to inform Commission action to consider a moratorium on disconnections until Xcel can develop a more robust set of measures to eliminate racial disparities in disconnections,” the groups wrote in April 12 reply comments (MN 23-452).

Xcel Energy, which had already hired a consultant to review the issues raised in the study, in a March 22 response attributed the racial disparities to “deeply entrenched economic and social reasons that are not driven by the energy system,” including the age of housing stock. It suggested targeting energy efficiency programs at low-income neighborhoods as part of the solution.

The study by Pradhan and Associate Professor Gabriel Chan looked at utility shutoffs, power outages, and the grid’s capacity for distributed energy by Census block across Xcel Energy’s Minnesota service territory. It also relied on data from the Council on Environmental Quality’s Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool, which maps disadvantaged communities as defined by federal law.

Xcel’s interactive service quality map allowed researchers to overlay various data at a granular level. “We could link this (data) with a lot of other variables,” Chan said.

In addition to utility shutoffs, the researchers found disparities in reliability, with communities of color almost 50% more likely to experience prolonged power outages than predominantly White areas.

“Across a battery of regression models, we find that living in poorer neighborhoods with a greater concentration of people of color is associated with a statistically and practically significant difference in the likelihood of disconnection from service due to nonpayment and the experience of extended power outages,” the report concludes.

Chan said the research does not necessarily suggest grid planners were intentionally racist. “But we do think that there’s a real opportunity here to think about how to affirmatively plan the distribution grid to address racial disparities that are caused by many other racialized systems.”

The research echoes inequities that have been found for everything from air quality and bike lanes to infant mortality and drownings, in which gaps similarly persist even after controlling for poverty.

“It would be almost surprising if there weren’t racial disparities” in utility service, Chan said.

Will Kenworthy, Midwest regulatory director for Vote Solar, said the type of racial disparities identified in the study are not unique to Minnesota.

“What we’re finding in Xcel service territory for reliability is consistent with what we’re seeing in Michigan and Illinois to varying degrees,” Kenworthy said.

The paper’s conclusion says the findings don’t necessarily imply deliberate racial bias but do highlight an “urgent need for policy interventions to protect low-income customers from disconnections, invest in marginalized communities, and equitably expand distributed energy resources such as solar and batteries.”

The energy equity and justice advocates, intervening as Grid Equity Commenters, attached the study with comments submitted in March as part of an Xcel Energy integrated resource planning docket. They argued that the disparities, and equity in general, needs to be part of any discussion about the utility’s system planning.

“Racial disparities in shutoffs have been repeatedly shown and the commission needs to do something about it,” said Erica S. McConnell, staff attorney for the Environmental Law & Policy Center.

Minnesota had a moratorium on utility shutoffs during the Covid-19 pandemic from early 2020 through August 2021. In addition to a study looking at the implications of reinstating that moratorium until racial disparities have been eliminated, the groups’ recommendations include proactive investments in grid reliability and distributed energy in disadvantaged areas.

Fresh Energy, a nonprofit policy advocacy group that also publishes the Energy News Network, separately filed comments on April 12 recommending that the commission require Xcel to track and report additional data regarding shutoffs and reliability in disadvantaged areas.

Utility shutoffs and outages can be scary, costly and “dramatic” for lower-income customers, said George Shardlow, executive director of the Energy CENTs Coalition, which works with Xcel Energy to help connect customers with energy assistance and conservation programs. Energy CENTs is not among the groups intervening in the Xcel planning docket.

Shardlow said targeting all customers in areas of high poverty with assistance programs, even for a limited time, could help reduce disconnections and energy burdens. That approach is in line with a proposed Xcel pilot program to offer automatic bill credits to all customers living within targeted, low-income areas where energy burdens exceed 4% of household incomes.

Xcel Energy’s comments framed the disconnection disparities as an issue of poverty. It says it has improved its efforts to avoid disconnections, contacting customers via phone and email for nine weeks to help connect them with assistance programs and offer long-term payment plans before shutting off service.

The company said its own analysis did not find a strong relationship between long-duration outages and the racial composition of the neighborhood. The frequency of long outages is so small, affecting less than 5% of households, and largely reflect the random paths of storms, it said.

“We recognize that even if the likelihood of extended or multiple outages remains small, the impacts of an electrical outage could be greater in disadvantaged neighborhoods that are disproportionately vulnerable to such emergencies,” the company said.

While equity and environmental justice are priorities for the company, Xcel said, it also pushed back on the discussions’ inclusion in the integrated resource planning docket, arguing that would duplicate conversations already happening elsewhere.

One surprising finding in the study could also point to potential solutions. In parts of Xcel’s territory, interconnecting distributed energy resources such as solar or batteries has become challenging due to congestion.

“This doesn’t look like an issue for low-income” areas, Pradhan said. “That’s a good point for energy poverty and energy equity” as solar installations could help reduce utility bills and stabilize the grid to reduce outages.

Minnesota Public Utilities Commission staff has tentatively scheduled a meeting to discuss Xcel Energy’s equity analysis with stakeholders in July.

Few places in California are as unforgiving for driving an electric car as the remote and sparsely populated Imperial Valley.

Only four fast-charging public stations are spread across the valley’s vast 4,500 square miles just north of the US-Mexico border, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. That means if you’re Greg Gelman — one of only about 1,200 Imperial County residents who own an electric car — traveling almost anywhere is a maddening logistical challenge.

“It’s been, I won’t say a nightmare, but it’s been very, very, very inconvenient,” Gelman said on a recent afternoon as he charged his all-electric Mercedes-Benz at a charging station in a Bank of America parking lot in El Centro. “Would I do it again? No.”

California’s electric charging “deserts” like the Imperial Valley pose one of the biggest obstacles to the state’s efforts to combat climate change and air pollution by electrifying cars and trucks.

Experts say the slow installation of chargers in California’s remote regions could jeopardize the state’s phaseout of new gas-powered cars. Under the state’s mandate, 35% of sales of 2026 models must be zero-emissions, ramping up to 68% in 2030 and 100% in 2035.

Nestled in the desert in California’s far southeast corner, Imperial County ranks dead last in electric car ownership among California counties with populations of 100,000 or more, according to a CalMatters analysis of 2023 data. Only 7 out of every 1,000 cars are battery-powered there, compared with 51 out of every 1,000 statewide.

High poverty and unemployment are a major factor in the region’s slow transition to electric cars, but its lack of public chargers are a big drawback, too.

People living in rural, low-income regions like the Imperial Valley have the least access to electric car chargers, according to a state Energy Commission analysis. More than two-thirds of California’s low-income residents are a 10-minute drive or longer from a publicly available fast charger.

Luis Olmedo, executive director of El Comite Civico del Valle, a nonprofit advocating for environmental justice, has battled for years against the Imperial Valley’s unhealthy air. Now he is making a bid to become its go-to supplier of charging stations for zero-emissions cars.

Olmedo isn’t waiting for businesses or the state to make chargers a reality in Imperial County. Instead, his group has embarked on a $5-million, high-stakes crusade to build a network of 40 fast chargers at various locations. It’s an open question whether his somewhat quixotic endeavor will succeed.

Electric car chargers “are an opportunity for us to be able to breathe cleaner air,” Olmedo said. “It’s about equity. It’s about justice. It’s about making sure that everybody has chargers.”

Esther Conrad, a researcher at Stanford University who focuses on environmental sustainability, said getting chargers in places like Imperial County is critical to California’s effort to transition to electric vehicles in an equitable way. Apartment dwellers and others who don’t have charging at home need nearby and reliable places to charge.

“When you have a rural community that’s low-income and distant from other locations, it’s incredibly important to enable people to get places where they need to go,” Conrad said.

A car is essential for traversing Imperial County, which is the most sparsely populated county in Southern California.

Its neighborhoods are vast distances from urban centers that provide the services that residents need: El Centro — its biggest town, home to about 44,000 people — is much closer to Mexicali, Mexico, than it is to San Diego, which is about a two-hour drive away, or Riverside, nearly three hours. Its highways and roads cross boundless fields of lettuce and other crops that give way to strip malls, apartments and suburban tracts — and then even more crops and open desert.

If you drive an electric car the 109 miles from El Centro to Palm Springs, your route takes you through farmland, desert and around California’s largest lake, the Salton Sea, which is also one of its biggest environmental calamities.

The Salton Sea has been receding in recent years, causing toxic dust to blow into Imperial Valley towns. The region’s air quality is among the worst in the state, with dust storms and a brown haze emanating from agricultural burning and factories in the valley or from across the border in Mexicali, a city of a million people.

About 16% of Imperial County’s 179,000 residents have asthma, higher than the state average. The air violates national health standards for both fine particles, or soot, as well as ozone, the main ingredient of smog; both pollutants can trigger asthma attacks and other respiratory diseases.

More than 85% of Imperial County’s residents are Latino, and Spanish is widely spoken here. Agriculture is a major employer, and many businesses are dependent on cross-border trade and traffic from Mexico. The county’s median household income is $53,847, much lower than the statewide median, and 21% of people live in poverty.

Now the discovery of lithium, used to manufacture EV batteries, at the Salton Sea has the potential to transform the region’s economy. State officials say the deposit could produce 600,000 tons a year, valued at $7.2 billion, and assist the U.S. as it tries to foster a domestic electric car industry that rivals China’s.

But Olmedo worries that when the mineral is removed from the valley, it won’t meaningfully change people’s livelihoods or their health. He points to examples in the developing world where local people have been left behind as extractive industries take what they need.

“We’re about to extract, perhaps, the world’s supply of lithium here, yet we don’t even have the simplest, the lowest of offerings, which is: Let’s build you chargers,” Olmedo said.

Last year, electric cars were only 5% of all new cars sold in Imperial County, compared with 25% statewide. Getting chargers into low-income and rural places will become more and more important as California struggles to meet its ambitious climate targets.

The Energy Commission estimates that California will need 1.01 million chargers outside of private homes by 2030 and 2.11 million by 2035, when more than 15 million electric cars are expected on the roads. So far the state has only about 105,000 nonprivate chargers.

Nick Nigro, founder of Atlas Public Policy, which researches the electric car market, said charging companies won’t locate chargers in regions with few electric vehicles.

“You need revenue, and if the EVs aren’t there, then your customers aren’t necessarily there, so you do have a legitimate chicken and egg problem,” Nigro said. “We have to look to public policy to help that market failure.”

The Biden administration will invest $384 million in California’s electric car infrastructure over five years. And state officials are investing almost $2 billion in grants for funding zero-emission vehicle chargers over the next four years, including some special grants in rural, inland areas for up to $80,000 per charger. Olmedo says the funding has been insufficient so he’s had to turn to donations and other sources of funding.

Patty Monahan, one of five members of the California Energy Commission, said “it’s particularly important that we see chargers” in the Imperial Valley and other low-income counties with poor air quality.

Imperial Valley has only four fast-charging stations open for public use, where chargers are capable of juicing batteries up to 80% in under an hour, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Three are in El Centro, with one exclusively for Teslas; another is in the border town of Calexico and was recently installed by El Comite. Six other stations offer only slower chargers.

Olmedo envisions a network of 40 publicly accessible chargers throughout the valley. El Comite is expecting funding from the California Energy Commission, and has received donations from Waverley Streets Foundation, the United Auto Workers and General Motors. The group is seeking more state funding.

Olmedo acknowledged that he is facing a slew of challenges with his project, including some local opposition and the high cost of installation and maintenance.

At a warehouse in the city of Imperial where El Comite stores the chargers, Jose Flores, project manager for the group’s charging initiative, said he and three colleagues spent four days in Santa Ana, about 200 miles north, at a facility managed by BTC, the company that makes the chargers that El Comite is installing.

They received training on installation and maintenance techniques, and discussed how not all chargers can be used by all electric vehicles. He learned about payment and cooling systems, and that the chargers might need more frequent maintenance because of Imperial Valley’s harsh desert conditions.

“We’re like a testing ground because we have poor air quality here due to the Salton Sea and being in a desert,” he said.

El Comite installed its first charger at its Brawley headquarters in 2022. Last December, El Civico pressed ahead with a more ambitious project: Four of their fast chargers are now operating in a park in the border town of Calexico.

Chris Aldaz, 35, a U.S. Postal Service worker who lives in Calexico, charges at home, but at times uses chargers at the group’s Brawley headquarters that people can use for free. It is a Level 2, which can take several hours to charge.

“The reason why I wanted to get an EV was that it was cheaper,” Aldaz told CalMatters. “I don’t want to be spending all this money on gas, and on maintenance, and it was better for the environment.”

Nevertheless, Olmedo’s electric car chargers have become a local political issue.

Maritza Hurtado, Calexico’s ex-mayor, and coordinator of a City Council recall campaign, said it was inappropriate for El Comite to have built four electric car chargers in a downtown park. The chargers were a distraction “from our police needs and our actual community infrastructure needs,” Hurtado said at a public hearing at the county’s utility, the Imperial Irrigation District, in January. She declined to speak to CalMatters.

“We had no idea they were going to take our parkland,” Hurtado said at the hearing. “It is very upsetting and disrespectful to our community for Comite Civico to come to Calexico and take our land.”

Olmedo hopes that the chargers ultimately will be something the county’s Latino community takes pride in.

“Put this in perspective: It’s a farmworker-founded organization, an environmental justice organization, that is building the infrastructure. It’s not the lithium industry. It’s us, building it for ourselves.”

Data journalist Erica Yee contributed to this report.

In 2022, decades of advocacy by the Louisiana Environmental Action Network to address poor air quality near industrial facilities took a significant leap forward.

That’s when the Biden Administration awarded more than $50 million through the Inflation Reduction Act to increase air quality monitoring in some U.S. communities historically overburdened by pollution.

A year later, LEAN, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group, got $500,000, which it used to deploy a fleet of mobile air monitoring vehicles. For three months earlier this year, the cars cruised up and down the Mississippi River, collecting continuous air quality data along a 300-mile route in southwest Louisiana known as “Cancer Alley.”

MaryLee Orr, LEAN’s executive director, has called the project a “dream” come true for her and the organization she founded in 1986.

“I get teary-eyed because for me, it’s been a lifetime of trying to find this kind of technology that communities could have,” Orr said during a virtual community meeting in January to roll out the project.

Now Louisiana will likely become one of the first states to push back on such community-led efforts. A Republican-backed bill headed to the governor’s desk will implement standards prohibiting data collected through some community air monitoring programs like LEAN’s from being used in enforcement or regulatory actions tied to the federal Clean Air Act.

“(Lawmakers) are making one hurdle after another to stop communities and discourage them from collecting any data by saying even if you collected it, we’re not going to count it; it’s not going to be important,” Orr said.

The industry-backed bill passed the House Wednesday on a 75-16 vote. The amended version returns to the Senate Monday, where an earlier version passed by an overwhelming majority.

What’s happening in Louisiana could be an indication of what’s to come elsewhere. A similar measure is up for consideration in the West Virginia Legislature.

Meanwhile, millions more in IRA grants are up for grabs for community-based groups, state, local and tribal agencies to do their own air monitoring in low-income and disadvantaged areas.

Localized air monitoring efforts allow marginalized communities overburdened by polluting industries to force transparency about the air they breathe and push state leaders to hold industry more accountable for harmful emissions.

Proponents of the new standards in Louisiana frame it as an attempt to bring more uniformity and standards to community air monitoring. But in a letter to one lawmaker, Region 6 Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Earthea Nance said the law would conflict with federal law, which states that “various kinds of information other than reference test data … may be used to demonstrate compliance or noncompliance with emission standards.”

Environmental advocates view the bill as a way to protect industry’s bad actors.

“The petrochemical industry is working with Louisiana legislators to inhibit community air monitoring because they know full well that they are polluting the air,” said Anne Rolfes, director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade.

Since it was established in 2000, the Louisiana Bucket Brigade has offered residents living near industrial facilities a low-cost, air monitoring tool approved by the U.S. EPA. The group’s name comes from the industrial-size buckets that contain monitoring equipment that members use to collect their own air samples around industrial facilities in their neighborhoods.

“It shows that they are scared of science and scared of the facts,” Rolfes said. “The power is on our side.”

Sen. Eddie Lambert, R-Gonzalez, whose legislative district includes three of the most heavily industrialized parishes in southeast Louisiana, sponsored the bill. It mandates that any air monitoring data used for enforcement and regulation must come from the most up-to-date EPA-approved equipment.

Analysis of that data can now only be conducted by labs approved by the state, which currently lists 175 accredited labs.

According to Stacey Holley, chief of staff for the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, the accreditation process can take between nine months and a year. The time is shorter for labs and research facilities wanting to amend their existing accreditation, she said.

Lambert did not return multiple emails or calls seeking comment on his bill. During a previous committee hearing, Lambert said the measure would ensure the public had accurate air quality information in this “age of the internet and disinformation.”

The Louisiana Chemical Association said the new standards don’t stop anyone from doing community air monitoring.

“Senator Lambert’s bill encourages that any air monitoring being conducted by individuals or organizations adhere to basic standards that EPA and LDEQ follow when testing air quality in the community,” Greg Bowser, president and chief executive officer of the statewide lobbying group, said in a statement. “These are the same standards a facility must meet when it complies with air monitoring requirements under their approved permits.”

Opponents say they need to do their own monitoring because the LDEQ is apathetic to concerns around air quality and the agency is slow to respond to spikes in pollutants detected by community air sensors.

“Essentially, every time a community member reports an air quality problem, whether it’s a dust cloud or toxic odors, DEQ doesn’t respond immediately,” said Kim Terrell, a research scientist and director of community engagement at the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic in New Orleans. “Part of that is that the agency is underfunded and understaffed. And part of that is that responding to residents’ complaints aren’t as big of a priority as they should be.”

Holley did not respond to inquiries related to those allegations.

In earlier committee testimony, Terrell said community-based air monitoring provides the best indication of air quality within certain geographical areas. She told lawmakers that reliable data can come from sources besides what the bill deems as the “gold standard” of air quality monitoring.

“There are other types of monitoring technologies that can provide useful data beyond the very limited techniques that are required in that bill,” she said.

Rolfes views the new standards and the most recent actions of Republican Gov. Jeff Landry, who took office in January, as troubling signs that Louisiana leaders want to dial back accountability and enact a pro-oil and gas industry stance.

“The legislators involved in this are showing us that … the petrochemical industry is worth more than the health of people in this state,” she said.

LDEQ’s air monitoring system consists of 40 stationary air quality sensors across a sprawling state that has among the highest emissions of toxic and greenhouse gasses in the country.

Terrell said LDEQ’s monitors are often insufficient to capture “real time” air quality data because many are too far away from “fence line” communities, don’t measure certain harmful pollutants or are unable to detect spikes depending on their position and wind flow.

She added that the kind of 24-hour, seven days a week air monitoring LEAN’s program did is a way to bridge those gaps.

LEAN was among four entities awarded a total of $2.4 million for community air monitoring in Louisiana. The other recipients were LDEQ, the Louisiana State University Health Foundation and the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice.

Adrienne Katner, associate professor at LSU’s School of Public Health, said the new standards won’t directly impact the nearly $500,000 the university received for a project collecting air quality data for a road construction project along Interstate 10 and the Claiborne Expressway in New Orleans.

But, added Katner, “We are concerned it might affect how we release the data should one of the community groups we work with want to take that data and file a complaint about air quality in the area.”

LEAN spent about $250,000 in 2023 to hire Aclima, a San Francisco-based pollution mapping company, which used its fleet of mobile air monitoring vehicles — Orr calls them “Harry Potter cars” — to collect samples around the clock for three months. The route included more than 20 cities in south Louisiana along the Mississippi, many of them majority Black and overburdened by industrial pollution.

The Aclima monitors sucked in air every second and uploaded the data for its science team to analyze and map for the public. The mobile monitors measured carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, fine particulates, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, black carbon and at least five other toxic emissions.

Earlier this year, LEAN’s mobile monitoring detected a methane leak in St. Charles, Louisiana that Orr said would have likely gone unnoticed. LEAN alerted state officials about it.

Orr said a full report of Aclima’s findings would be released in the coming months.

“I think there are going to be some surprises for people,” she said. “I think there are some areas where maybe people wouldn’t have expected things to be high, and they are. And then I think there’s places where you thought there might be huge, bigger numbers, and there weren’t.”

Should the governor sign Lambert’s bill into law before then, the findings likely would be disregarded by LDEQ. That’s because Aclima — named one of Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential Companies for its hyperlocal air pollution and greenhouse gas mapping — is not listed among the laboratories accredited through LDEQ.

Orr said LEAN has no plans to abandon its citizen monitoring effort. The group will use the rest of the IRA funds to install stationary air sensors.

“They’re saying they are not taking away air monitoring, but it seems like they want to take the teeth out of it,” Orr said. “They’re taking away the thing that seems to scare the people who are behind this bill, and that’s people having the right to know what they’re being exposed to.”

Floodlight is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.

OIL & GAS: A Navajo Nation resident and advocate pushes back against an oil and gas company’s proposal to convert a water well into a wastewater injection site near his family’s home. (Capital & Main)

ALSO:

CLIMATE: California Gov. Gavin Newsom touts $11 billion in climate projects funded by the state’s greenhouse gas cap-and-trade program over the last decade, but critics say the efforts haven’t done enough to reduce pollution. (Los Angeles Times)

SOLAR:

CLEAN ENERGY:

UTILITIES: An Arizona nonprofit prepares to help a growing number of Phoenix residents pay their utility bills after experiencing unprecedented demand for the aid last summer. (ABC 15)

COAL: Mining companies in Wyoming hint at potential layoffs at Powder River Basin facilities after larger-than-expected production decreases. (WyoFile)

HYDROGEN: A company breaks ground on a $550 million green hydrogen production hub in Arizona. (Hoodline)

ELECTRIC VEHICLES:

TRANSMISSION:

COMMENTARY: A California editorial board urges Los Angeles leaders to make climate goals legally enforceable and “not mere aspirations to be shrugged off by finger-pointing bureaucrats.” (Los Angeles Times)