It’s been a bad week for the U.S. energy transition.

President Donald Trump and congressional Republicans effectively repealed large swaths of the landmark Inflation Reduction Act last Friday, a move that will set back the nation’s efforts to decarbonize just as they were gaining steam.

But the United States is not the only country in the world. It’s one of the biggest emitters, true, but it’s responsible for only about 13% of global carbon dioxide emissions.

And luckily, even as Trump hitches the U.S. to fossil fuels, the world is continuing to move quickly toward cleaner sources. Let’s take a tour of some global energy-transition bright spots.

In China, the world’s biggest carbon emitter, wind and solar capacity overtook coal and gas in the first quarter of 2025 — a first, according to a Global Energy Monitor report released this week. The country is still building and using immense amounts of fossil fuels, but reports suggest its emissions may finally be in reverse.

In the European Union, solar was the largest source of electricity across all of June. It’s the first time solar has led the pack for an entire month in the EU, according to a new Ember report, producing 22% of the region’s electricity. Meanwhile, coal fell to its lowest-ever level, a reflection of the region’s push to eliminate the dirty fuel: Ireland shuttered its last coal plant in late June, becoming Europe’s 15th coal-free country. Italy and Spain are slated to close their last major coal plants this summer, too.

Across the entire world, $2 is now invested in clean energy, efficiency, and the grid for every $1 invested in fossil fuels. That’s serious progress, and a big reason why clean energy is growing so rapidly worldwide. Last year, more than 90% of the new electricity built globally was clean energy. Meanwhile, EV adoption is set to leap 25% this year, compared with 2024, setting yet another record even amid headwinds in the U.S., according to BloombergNEF. More than one-quarter of new passenger vehicles sold worldwide will be battery-powered.

To be clear, the trajectory the world is on right now is not fast enough to meet global climate commitments. All of the progress mentioned above needs to accelerate further — and the U.S. resisting the energy transition is a big deal. But with or without the U.S., the global energy transition is happening, and a future that’s powered by solar, wind, batteries, nuclear, and other forms of carbon-free power is on the way.

Megabill fallout

One week ago today, Trump signed the GOP megabill into law and changed the trajectory of the U.S. energy transition with the stroke of a pen.

The law made deep cuts to the Inflation Reduction Act, the national climate law passed by the Biden administration in 2022. As a result, the U.S. is now expected to install clean energy at a slower pace, sell fewer EVs, and emit a lot more carbon dioxide in the coming years. Oh, and energy prices are going to rise, too. If you’re looking for a piece to share widely that covers the basics, try this one I published on Monday.

Every sector faces slightly different challenges from the law. Even geothermal energy, a favored clean energy source among Republicans, faces a rocky road, Canary’s Maria Gallucci reported this week. The law could have been worse for solar and wind — but it will still pose big challenges, Jeff St. John reports. It could even prevent some fully permitted offshore wind projects from moving forward, Clare Fieseler writes.

Trump’s pro-coal push faces challenges

A month and a half ago, the Department of Energy ordered two fossil-fueled plants that were on the brink of shutting down to stay open. It might have been an opening salvo in a major effort from the Trump administration to keep aging, dirty coal plants open past their planned close dates, Jeff St. John reported this week.

The move comes as the Trump administration, and in particular DOE Secretary Chris Wright, frequently refers to renewable energy as unreliable and calls for more fossil-fuel use instead. A new DOE report furthers that line of argument, though it has been criticized as relying on flawed assumptions. Meanwhile, examples pop up near-weekly of how clean energy actually helps the grid. During a heat wave in late June, for instance, solar and batteries helped save New England from potential blackouts, Sarah Shemkus reports for Canary Media.

Now, state regulators and environmental and consumer groups are challenging the legality of Trump’s pro-coal intervention, arguing that the grid can be safely run without it.

More reliable in Texas: Texas has dramatically increased its grid reliability and maintained affordable electricity prices as it’s integrated more solar, batteries, and wind, undermining Trump’s repeated claims that renewables make the grid unstable. (Reuters)

Rooftop regression: Rooftop solar installations are set to plummet following the GOP megabill’s repeal of a longstanding federal incentive, with analysts estimating between 40% and 85% less demand over the next decade. (Washington Post)

Ford-ging ahead: Ford says last-minute changes to Republicans’ big budget bill saved tax credits that it’s counting on as it builds a $3 billion Michigan battery factory. (New York Times)

Salt in the wound: President Trump directs the Treasury Department to strictly curtail which projects can access wind and solar tax credits before they are phased out in 2028 under the new Republican budget bill. (The Hill)

Permission denied: About one in five counties across the U.S. have passed laws to restrict or outright ban construction of new solar and wind farms, and are curtailing battery storage facilities too. (Heatmap)

A tough turn for tribes: Tribal leaders say the new federal tax and spending law will cause widespread clean-energy job losses in their communities and jeopardize climate projects. (Grist)

Drilling declines: A Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas survey shows regional oil and gas production declined in the second quarter of 2025 amid global unrest and Trump administration trade policies, and many operators say they now plan to drill fewer wells than they predicted this year. (Axios)

Heat pumps are cool: If you’re thinking about getting central air conditioning at your house — or replacing your existing system — have you considered a heat pump instead? (Canary Media)

Time to go car shopping: And if you’re contemplating getting an electric vehicle anytime soon, here’s some advice: Do it before the end of September, when the federal tax credit now sunsets under the GOP law. (Canary Media)

Congress moved one step closer to passing President Donald Trump’s “One Big, Beautiful Bill” this week — and with that, one step closer to spiking power bills across the nation.

The bill would rapidly phase out tax credits for clean energy, slowing the construction of solar, wind, and battery projects, which made up over 90% of new electricity connected to the grid last year.

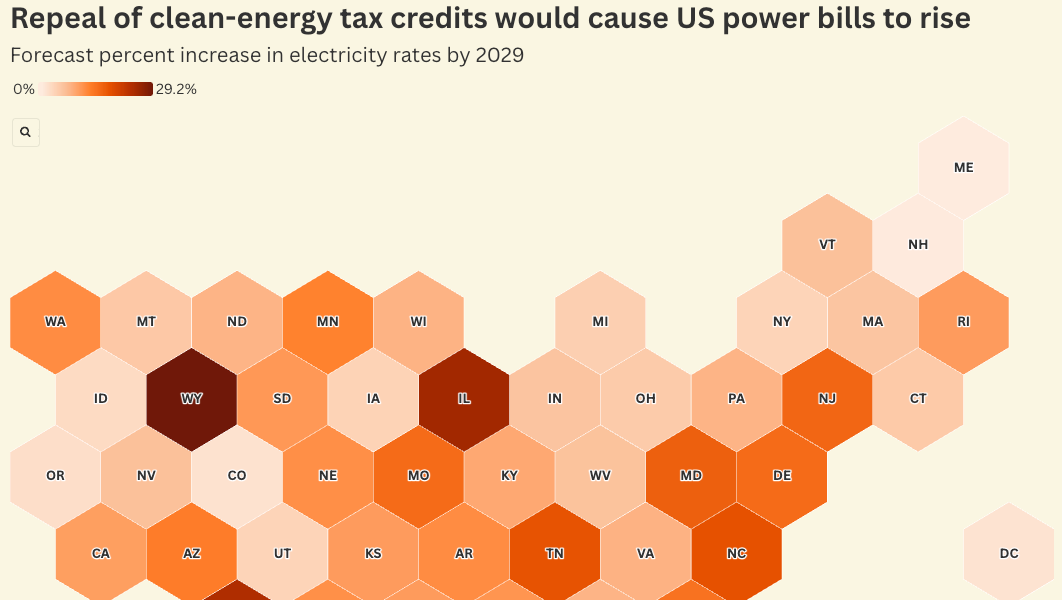

Repealing those tax credits would come at a steep cost to utility customers in every state, according to NERA analysis commissioned by the Clean Energy Buyers Association. The most impacted states could see electricity prices rise by nearly 30% by 2029.

The Senate bill passed Tuesday would require solar and wind projects to either start construction within a year of the bill’s passage or start service by the end of 2027 to receive the tax credits. Those that begin construction after this calendar year would be subject to “foreign entity of concern” restrictions so difficult to comply with that experts have said they amount to a “backdoor repeal.” Batteries, nuclear, and geothermal have a longer runway to claim the credits but would have to deal with the same unworkable foreign-entity strictures.

The bill is now being considered by House Republicans, who have set a self-imposed deadline of sending the bill to Trump’s desk by Friday. A previous version of the bill passed the House in May by just one vote.

Clean energy is the cheapest and easiest way to get power onto the grid. With demand for electricity nationwide rising due in large part to AI data centers, swiftly bringing affordable energy online is more crucial than ever.

But if tax incentives are repealed, fewer solar, wind, and storage projects will be built. Between now and 2035, the U.S. could see 57% to 72% less new clean-energy capacity come online than it would have with the tax credits in place, according to Rhodium Group. Meanwhile, new gas construction likely can’t make up the difference in the near term: Developers who want to build new gas power plants face wait times of up to five to seven years for turbines.

Rising power demand plus slower power-plant construction is a recipe for higher electricity bills.

Households and businesses in Wyoming, Illinois, and New Mexico would see the biggest jump in energy costs should the tax credits be repealed. Nationwide, electricity prices would increase by an average of 7.3% for households and 10.6% for businesses, worsening the increasingly steep energy costs Americans face.

The biggest loss, however, would be for attempts to decarbonize the U.S. power system. The Inflation Reduction Act, the U.S.’s first real stab at climate policy, had put the country nearly on track to cut carbon emissions in line with global climate commitments. Under this bill, however, U.S. efforts to move away from fossil fuels are certain to be slowed — even as the rest of the world speeds ahead toward clean power.

Dean Solon stands out as one of the very few self-made billionaires to emerge from the U.S. solar industry, following the tremendous 2021 initial public offering on the Nasdaq of his solar-equipment firm Shoals.

But a few weeks ago, as he and I found seats outside the Midwest Solar Expo in a far western suburb of Chicago, it was clear the major cashout hadn’t changed his style. Solon, age 61, was dressed not in Balenciaga or Louis Vuitton, but his trademark jean shorts and athletic sneakers.

“I’m gonna go from a large Dunkin Donuts to an extra-large Dunkin Donuts now,” he said. “I still, to this day, drive a 2017 Chevy Bolt, 100% electric. I still live in the same house. I didn’t do it for the money then, I don’t do it now.”

In fact, Solon’s instinct to tinker and solve problems has thrust him back into the solar manufacturing space at the industry’s most chaotic moment in years.

“The renewables building is on fire, and it is hot as fuck, and everybody’s running away from the fire,” he said. “We have asbestos-clad underwear on. We have our fire suit on, and we got a hose, and we’re running into the fire.”

Solon has decided to compete in these dire circumstances by essentially building the entire menu of items needed for a modern solar, battery, or microgrid project, and designing all the pieces to fit together seamlessly. His new firm, Create Energy, will sell developers solar modules, trackers, batteries, inverters, power stations, and other auxiliary equipment. The goal is to save customers time and effort compared to buying separately from a tracker vendor, a module vendor, an inverter vendor, and so on, and then assembling all those components with separate crews.

It’s an ominous time to start a new solar manufacturing business in America, to say the least. After a booming few years following the implementation of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act and its various, generous clean-energy manufacturing incentives, firms now find themselves squeezed between fluctuating tariffs and the detonation of those same incentives, following President Donald Trump’s signing of the One Big, Beautiful Bill Act last week.

What better moment to check in with one of the most singular voices in the solar industry, who has survived and thrived through the solarcoaster of the last two decades without wavering in his commitment to American manufacturing?

Solon’s previous company Shoals originally made automotive parts for Bosch back in the ‘90s. But after the North American Free Trade Agreement went into effect, lifting most tariffs between Canada, the U.S., and Mexico, Bosch wanted to relocate its suppliers to the latter nation, and Solon refused to move his operation out of Tennessee, he recalled.

Around that same time, he got an inbound request from a budding solar enterprise that needed some manufactured junction boxes and cable assemblies; that upstart turned out to be First Solar, pretty much the only U.S. panel manufacturer that has excelled over the last few decades (and whose stock has been on a tear as Congress prepared to revoke tax credits for solar projects that use Chinese-made materials).

Once he made the jump into solar equipment in the early 2000s, Solon kept manufacturing in America, even as installers and developers embraced cheaper Chinese products and U.S. cell and module manufacturing collapsed.

“Solar makes sense, with or without incentives; Buying American-made products, even better,” Solon said. “Listen, I fly the American flag like crazy. I grew up in the ‘70s working on American cars. I’m a gearhead my whole life. I love American-made products, and I’m gonna push it.”

That ethos continues in the new venture. The strategy is to build high-quality equipment and find customers who understand its value, because they’re investing with a longer-term mindset.

“We’re not looking for every Tom, Dick, and Harry that’s trying to flip a project to build it as cheap as possible with garbage,” he said. “I’m looking for the [independent power producers], the big power companies, who want to buy systems that are going to last for decades.”

In theory, a company with this attitude would welcome tariffs, which raise the cost of cheaply produced competition from Chinese factories. The last few months have seen new tariffs aplenty, though Trump has waived some within days or weeks of announcing them. But while tariffs are often billed as helpful to domestic manufacturers, President Trump’s tariffs are also causing complications for the American factory buildout.

For starters, Trump’s blanket tariffs on all Chinese goods impact manufacturing equipment produced in that country. Not only does China make most of the world’s solar panels — it also makes many of the machines required to manufacture solar.

“To be clear on this point, there’s no better-built machines for solar than Chinese equipment, end of story,” Solon said. “That’s how good it is. It’s heads and tails better than anywhere else you could get machinery.”

“It was easy to order machinery, but then once the tariffs hit, there’s a lot of machinery just sitting in ports in China that hasn’t left,” he added.

Even if Solon could get his hands on that equipment without exorbitant price hikes, the U.S. lacks enough production of solar cells — the component that actually converts sunlight into electricity — to meet the demand for domestic module assembly. Factories that can’t obtain the limited domestic cells need to import them, but the so-called reciprocal tariffs Trump has announced on much of the world, and then delayed, have scrambled the economics for cells from outside the U.S.

Create is making other products at its Portland, Tennessee, factory, but the timeline for making solar modules in-house has been pushed back due to the macroeconomic headwinds.

A decade ago, solar module costs started to plunge, and the price of solar-generated power fell along with it. That has propelled solar to the front of the pack for new power plant construction. But lately the slope of cost declines has leveled off, and incremental module improvements do less and less to push the cost of solar power lower.

Solon is stepping into that mature marketplace, so he has to bring something new to the table to stand out. After years of making the electrical connectors needed to hook up solar panels into a functioning power plant, he realized he could eliminate several steps for installers with clever design hacks.

Today’s standard solar-plant construction process creates inefficiencies. “Everyone is this separate crew working on the same rows over and over and over ‘til they do it in the next location,” Solon said.

A singular project might have different crews clear the earth, pound the posts, add torque tubes, bolt the modules in place, check the torque on the bolts, handle the electrical work, and then clean up the site, he said.

The new products from Create come with electrical connections pre-wired into the modules and the torque tubes of the trackers. Installers can easily snap everything together, at which point, Solon insists, the systems won’t need any more maintenance.

Solon’s goal was to make installation so easy that it would be doable for an avatar of the modern man that he refers to as “Mr. Hot-Pocket Muncher,” who is “happy living in mommy’s basement eating Hot Pockets and playing 12 hours of Xbox.”

“Take my module, and grab Mr. Hot-Pocket Muncher,” Solon envisioned, after showing me an AI rendering of the character, which his colleague on hand advised him against making available for publication. “He picks it up. He clicks it on the torque tube. Did I hear it click? Yes, I’m done. Grab the next one. Click, yes. All the wiring is done. All the mechanical connections are done, and they’re non-serviceable. There’s nothing for an [operations and maintenance] crew to ever do again.”

That vision would threaten a number of specialized jobs in the solar installation and maintenance business. But it would also deliver more efficient construction, so the same workforce could theoretically deliver more clean power in the same amount of time. If Solon can pull it off, that kind of benefit could be valuable as the industry stares down the loss of its decades-long tax-credit regime.

Solon doesn’t deny that the solar industry writ large is heading for a contraction, but he rejects the more apocalyptic outlooks some fear for the sector. Instead, he thinks it’ll be a reset for the industry after the bounty of Biden-era policy supercharged the pace of activity.

“Right now, the solar business is a drunk pirate that partied like a rock star all last night,” Solon mused. “We woke up, we’re hung over as hell, and we’re reaching for our wallet and our keys, and we can’t find either one of them. And we wonder what the hell happened? I think we’re gonna be hung over for about six months to a year.”

The wave of bankruptcies has already begun, taking down longtime industry stalwarts like solar loan provider Mosaic, rooftop solar financier Sunnova, grid-battery integrator Powin Energy, and more.

It’s not a bad time to have a billion dollars in the bank and several decades of manufacturing experience.

“If you’re in a consolidated market [and] people are going out of business, who are you going to run to to get your products and services?” chimed in Create’s chief of staff, Joe Fahrney, who was sitting next to Solon at the Midwest Solar Expo. “So people are lining up to buy from Dean Solon, because they know Dean and Create will be in business over the next 20, 30, 40, 50 years.”

“This time it won’t IPO though,” Solon interjected. “I’m not giving up control, because I want this little baby to run for hundreds of years.”

Two years after the last attempt to build out wind farms in Maine’s northern reaches fizzled, the state is again gearing up to seek developers to build at least 1,200 megawatts of land-based wind capacity and a transmission line to carry the electricity produced to the central part of the state. At the same time, grid operator ISO New England is accepting proposals for new transmission infrastructure that will allow that power to flow to the rest of the region.

For wind power advocates, these moves have sparked hope that a new source of renewable energy may finally be developed in the region.

“After talking about this for the last 15 years, I feel like there’s a light at the end of the tunnel,” said Francis Pullaro, president of clean-energy industry association RENEW Northeast. “It’s definitely complicated and a big undertaking, but I think the state has realized what a great opportunity northern Maine wind provides.”

Maine and most of its neighboring states have ambitious emissions-reduction targets: Maine just adopted legislation calling for 100% clean energy by 2040, for example, and Massachusetts and Rhode Island both aim to be carbon-neutral by 2050. Offshore wind has been a major part of the states’ strategies for transitioning away from a system that now leans heavily on natural gas for electricity generation. However, as the Trump administration throws up roadblocks to offshore wind development, it becomes even more important to tap into land-based wind to keep progressing toward a cleaner energy future, supporters said.

“It’s a really important medium-term piece of the puzzle in how we reduce our dependence on gas as a region and for our state,” said Jack Shapiro, climate and clean energy director for the Natural Resources Council of Maine, an environmental advocacy group. “It’s a pretty big deal.”

Plans to build onshore wind in northern Maine’s remote Aroostook County have come and gone several times over the past two decades. In 2008, then-Gov. John Baldacci (D) signed a law setting a goal of bringing 2,000 MW of wind power online by 2015 and 3,000 MW, including some offshore wind, by 2020. As of this year, the state has 1,139 MW of onshore wind operational and no offshore turbines.

Aroostook County — with its strong winds and low population density — has long been considered a prime area for building turbines, but its promise has not been realized. One of the major obstacles has been the lack of transmission lines to carry power from the forests of northern Maine to the lightbulbs and dishwashers of Massachusetts and Connecticut. Most of Aroostook County is served by an electrical system connected only to Canada, with no direct links to any U.S. power grid. Building the needed lines is a complex, costly undertaking that has repeatedly stymied efforts to get wind generation up and spinning.

“For the southern New England states where all the load is, [northern Maine] always was a fairly distant resource,” Pullaro said. “The lack of transmission has always been the barrier.”

In 2013, Connecticut selected a planned wind development in Aroostook County — EDP Renewables’ Number Nine Wind Farm — to provide 250 MW of power to the state. By the end of 2016, the project had been cancelled, with EDP citing the lack of transmission capacity to get the electricity to customers farther south.

In the final days of 2022, Massachusetts agreed to buy 40% of the power generated by the proposed King Pine wind farm in Aroostook County, a deal that seemed to give the 1,000-MW project the financial security it needed to proceed. By the end of 2023, however, a separate agreement with LS Power to build a transmission line connecting the development to the rest of New England fell through over pricing disagreements, undermining the prospect of wind development.

“The contract negotiations were not successful, and the project stalled,” said Dan Burgess, director of the Maine Governor’s Energy Office.

Now the state has gone back to the drawing board. This time around, however, the plans are getting an unprecedented boost from ISO New England. The regional grid operator in late March issued a request for proposals for the development of a transmission project connecting the Maine town of Pittsfield to points farther south in New England, shortening the distance the power lines from future Aroostook County wind farms will have to travel. A plan could be chosen as soon as September 2026.

Meanwhile Maine utilities regulators released a request for information to collect feedback from developers, industry members, and other stakeholders to help plan and schedule its next procurement. There has been a robust response to the request, though most comments were filed confidentially, said Susan Faloon, spokesperson for the Maine Public Utilities Commission. The tentative plan is to open up for proposals by the end of the year, she said.

Whether the next attempt will be successful hinges on a few factors, starting with its ability to financially weather Republicans’ scaleback of federal clean-energy tax credits and the administration’s continued, evolving hostility to renewable energy projects. Trump halted federal permitting and leasing for wind projects on his first day in office, and although 99% of onshore wind farms are built on private property, they still could need environmental permits from the administration.

“The economics of any specific project is really uncertain right now because we don’t know what will happen,” Shapiro said.

Still, Pullaro said, history suggests that onshore wind development could survive the blow of losing federal support. The grid needs more energy, and land-based wind is one of the least expensive power sources to build, even without incentives, while the cost of new natural gas generation is going up, according to a recent report from investment bank Lazard.

“From the industry point of view and for consumers, wind is still a good deal no matter where the tax situation is,” Pullaro said.

Tweaks to the state’s timeline for issuing a request for proposals and choosing a project could also increase the likelihood of success, Pullaro said. A wind development stands a much better chance of succeeding, he said, if another state commits to buying power from it, giving it a revenue stream it can count on. Getting Massachusetts on board could be even more crucial than federal support, he said.

Massachusetts is still authorized to enter into another such agreement until the end of the year, and Gov. Maura Healey (D) included in a supplemental budget bill a provision that would extend this authorization to 2027, but the legislation is still pending. In the meantime, if Maine waits until the end of 2025 or into 2026 to launch a new solicitation, the eventual development could lose its chance to secure a deal with Massachusetts. Pullaro, therefore, would like to see Maine issue a request for proposals by September.

“The economics don’t work for Maine going it alone,” he said.

As some state legislatures try to roll back clean energy measures, a successful policy for community solar in Minnesota has survived a political fight to end it.

Earlier this month, lawmakers ditched language from the state’s energy omnibus bill that would have terminated a successful state community-solar program in three years — and quashed the build-out of 500 megawatts of planned projects, according to advocates.

“I am absolutely thrilled that the community solar program will continue, [particularly] for the communities and individuals that will benefit from it,” said Keiko Miller, director of the community solar program at advocacy group Minneapolis Climate Action. “This really is a way of reducing household energy burden for those who have been left out [of the energy transition] traditionally, as well as increasing the availability of renewable energy resources.”

Minnesota’s Community Solar Garden program is crucial as the state aims to decarbonize its power system by 2040, Miller said. “There is absolutely no way we can get there without community solar being part of the portfolio.”

Community solar projects, which are typically up to 5 megawatts, make it easier for households to tap into the value of solar. Customers who might not be able to install photovoltaic panels on their own roofs, including renters and low-income families, can sign up for a shared solar project sited elsewhere, like on a community center’s roof or in a farmer’s field. Also known as community solar gardens or farms, they can guarantee subscribers a discount on electricity costs.

Minnesota was an early leader in the shared-solar approach, having started the state program in 2013. Last year, the North Star State ranked fourth in the nation for installed capacity with 939 megawatts, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. That’s almost one-third of the state’s total solar capacity of 2.9 gigawatts.

The state revamped its solar garden initiative in 2023 to ensure that more households and lower-income customers would benefit from community solar projects. Lawmakers didn’t assign the initiative an expiration date at the time.

In late March, two Democrats and one Republican introduced Senate File 2855, a bill that would’ve sunset the community solar program in 2028. Senators then rolled the plan into their version of the energy bill.

Minnesota-based utility Xcel Energy supported terminating the program; in a March 26 hearing, a company representative criticized community solar as a costly way to deploy clean energy compared to utility-scale installations. Notably, companies other than utilities can develop community solar projects, and Xcel Energy doesn’t earn a profit on energy infrastructure it doesn’t own.

But the utility and other opponents aren’t accounting for community solar’s wide-ranging benefits, such as avoided transmission costs, the reduction in peak demand on the grid, and resilience, said Patty O’Keefe, Midwest regional director of national nonprofit Vote Solar.

In 2024, the Minnesota Department of Commerce, which oversees the state program, found that it’s expected to deliver $2.9 billion in net benefits over the next four decades. While the initiative is projected to increase bills by 2% to 3% for non-subscribers who aren’t considered low to moderate income, community solar is expected to lower energy bills for participating households by 3% to 8%.

Ultimately, lawmakers stripped the repeal language from the energy bill following pushback from community solar champions in the Legislature, including Democrats Rep. Patty Acomb, Senate Majority Leader Erin Murphy, and Rep. Melissa Hortman, O’Keefe said. (On June 14, Hortman and her husband were assassinated at their home in an act of politically motivated violence.)

Droves of supporters also helped save the state solar-garden program; they testified at hearings, marched, and protested, O’Keefe said. By her count, roughly 100 Minnesotans, including community solar subscribers, farmers, and clean energy advocates, called on legislators to reject the repeal.

The win for community solar in Minnesota comes as the broader solar industry — and the already-struggling rooftop solar sector in particular — faces serious federal headwinds. The Trump administration’s rapidly fluctuating tariffs and the looming repeal of solar and wind energy tax credits in the budget bill threaten to make solar more expensive to build. That could throw cold water on the record-breaking pace of solar deployment the U.S. has experienced in recent years.

But in Minnesota, at least, a major source of clean energy endures.

“This is a victory for the community solar movement,” O’Keefe said. “It just shows that even with a … forceful effort to try and repeal the entire program, we had enough power between the public and clean-energy champions to fight it back — and really send a message that Minnesota benefits from community solar.”

Massachusetts last week enacted a revamped version of its solar incentive program that developers and advocates say should keep the state’s solar industry moving forward even as the Trump administration pushes to undermine federal support for clean energy.

“In short, the program makes Massachusetts a very healthy market for solar,” said Nick d’Arbeloff, president of the Solar Energy Business Association of New England. “We’ll still be able to present a compelling case to an investor.”

The newest iteration of the Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target program — generally called SMART — makes fundamental changes to the structure of the incentives to be more responsive to market conditions. Other provisions aim to make the benefits of solar available to more low-income residents, protect valuable open space from development, and encourage placement of panels on rooftops and in parking lots.

The state filed the new rules as emergency regulations, allowing them to go into effect immediately.

The move comes just in time, according to solar developers. The previous version of SMART hasn’t been effective in quite some time, they say. While draft regulations for this newest version of SMART were first released nearly a year ago, and a final revision was expected in fall 2024, months went by without new rules.

“The uncertainty we were facing was confusing inventors, was killing projects, and could have done even more damage,” d’Arbeloff said.

In the meantime, President Donald Trump took office and Republican legislators have been working on a budget bill that seems likely to accelerate the elimination of federal renewable energy tax credits. Massachusetts solar developers became increasingly worried they would find themselves in a “valley of death,” with neither state nor federal support, at least for a time, said Ben Underwood, co-CEO of Resonant Energy, a Boston-based solar company that specializes in projects serving environmental justice communities.

Developers, therefore, heaved a sigh of relief when the new state regulations were filed. The reimagined program will start accepting applications on October 15, which will give developers a chance to get projects in place and investors lined up, even with the threat of disruption at the federal level, Underwood said.

“Now we and other members of the industry can start to plan for the incentives,” he said. “It gives us a much easier transition in case federal incentives are taken away.”

Launched in 2018, SMART pays the owners of solar systems a set rate per kilowatt of energy generated by their panels. The base rate depends on project type, location, and size. Projects advancing goals the state supports — serving low-income communities, for example, or building on a closed landfill — receive a boost, known as an “adder,” to their base rate.

The program was initially designed to lower its rates as more solar installations were built. The thinking was that, as the solar industry became more established, the cost of developing projects would go down and developers would need less financial support to be viable.

For years, SMART helped drive solar growth in the state: From 2019 to 2021, annual solar installations more than doubled. Then the Covid-19 pandemic intervened, upending supply chains and sparking inflation. At the same time, SMART compensation rates had fallen, as intended. Suddenly, the incentive payments weren’t enough to cover growing costs, and the industry took a hit. In 2024, less than half as much solar capacity was installed than in 2021.

“You were finding that the incentive level for many projects was, in fact, zero,” d’Arbeloff said.

The new rules jettison the old system of declining rates, replacing it with one that resets the compensation and program size each year, allowing the program to adjust to future unexpected market changes. Annually, the state will conduct an economic analysis that considers progress toward emissions reduction goals, regional and national solar costs, current and historic program participation rates, and land-use and protection goals, and will use the results to set compensation for the coming year. Adders will still be part of the system, and will also be adjusted annually, as needed.

“We can understand the costs, we can understand the size of the program, and we can make adjustments with ratepayers in mind,” said Elizabeth Mahony, commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources. “That’s really important for ratepayers and the development community — we’re going to be so nimble.”

For 2025, the program will be open to up to 450 megawatts of capacity. The base compensation rates will be set after the state completes a new economic analysis in the next few months, Mahony said.

The revised regulations also aim to increase the amount of money flowing to solar projects serving low-income residents. For a development to receive an adder as a community shared solar project, it must allocate at least 40% of the bill credits it generates to low-income households and guarantee these customers a savings of at least 20%, compared with the basic retail price.

“It represents a substantial move toward having greater value for low-income community shared solar participants,” Underwood said. “It’s really good to see that.”

The new regulations also target ongoing tensions about how best to site solar projects while still protecting wildlife habitats and agricultural land.

“We hope the way this works is it pushes folks to do more on rooftops, to do more on canopies, and to do more on previously developed land,” said Michelle Manion, vice president of policy and advocacy for the Massachusetts Audubon Society. “When it comes down to the actual numbers, then we’ll see how well it actually works.”

Certain categories of land with particular environmental value have been declared ineligible for solar development going forward. Projects built on other open spaces will have to pay a mitigation fee that will be determined by a list of factors, including the land’s carbon storage and agricultural potential, the parcel’s ecological integrity, the cumulative impact of the proposed development and others in the area, and location of the planned project relative to grid infrastructure.

“It’s a good way to be a little more strategic about siting solar,” said Erin Smith, clean grid director for the Environmental League of Massachusetts.

These measures are combined with provisions that encourage more development on the built environment. The regulations expand the definition of a solar canopy that qualifies for an adder — which was limited to projects over parking lots, canals, and pedestrian walkways — to include any array raised high enough off the ground to allow the use of the area beneath for another function. The rules also create a new category of adder for panels mounted above other equipment atop buildings, allowing more efficient use of rooftop space.

Though the emergency regulations process put the new rules into effect immediately, the state must still hold three hearings within 90 days to gather public feedback and get final approval from utility regulators. Some tweaks to the program could be coming, but state officials are confident they’ve got the basics right.

“There are quite a few projects that have been waiting for this to come out,” Mahony said. “We believe this is one of the best ways we have to build energy generation in the next few years.”

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the week” column.

Wind and solar are on the rise worldwide — here are the 10 countries that rely on the clean-energy sources most for their electricity.

All of these countries used wind and solar to produce at least one-third of their electricity in 2024, according to a new report from the Energy Institute. For leading countries such as Denmark, Djibouti, and Lithuania, that figure was in the range of two-thirds or more.

Those numbers are much higher than the global average: Overall last year, wind and solar accounted for 15% of global power generation, up from 13% in 2023.

To be clear, China is still by far the largest producer of solar and wind energy in the world in terms of volume. The country generated 1,836 terawatt-hours of wind and solar last year. All of Europe, for comparison, generated 990 TWh over the same period. But despite that huge amount of renewable energy generation, China received a much lower share of its power from solar and wind in 2024 than the 10 countries on this list — just about 18%.

The list is mostly populated by smaller countries, but it does include some large economies like Germany and Spain. In Germany, wind and solar accounted for a combined 43% of power. In Spain, 42%. (Spain recently suffered a countrywide blackout for which its high share of renewables was blamed. The true culprit, according to a government report released last week, was poor grid planning.)

By the end of the decade, the International Energy Agency expects wind and solar together to account for nearly 30% of global electricity generation. So, while only a handful of countries boast high levels of renewable energy penetration today, many more will join their ranks in the coming years, as wind, and especially solar and batteries, get cheaper and harder to refuse.

A big-budget offshore wind project that would clean up a contaminated California port and turn it into America’s first hub for floating wind turbines is the latest target of an increasingly emboldened national anti-offshore wind movement.

Representatives of a D.C.-based conservative think tank, Committee for a Constructive Tomorrow (CFACT), and a local California community group asked the U.S. Department of Transportation early this month to cancel a $426 million grant issued last year to repurpose the Redwood Marine Terminal in Northern California’s Humboldt County for wind. If successful, they could stymie the state’s plan to generate up to 5 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030 and 25 gigawatts by 2045.

Anti-wind activists told Canary Media they are looking to capitalize on the “timing” of a recent implosion of offshore wind plans in Maine, which — like California — sought to pioneer floating turbine technology in this country. Currently, all turbines operating or under construction in U.S. waters are fixed to the seafloor.

The move represents a westward spread of anti-wind activism from the East Coast, where longtime organized opposition has found sympathetic ears as it petitions the Trump administration to tank permitted projects.

For example, in February, groups lobbied for a halt to offshore projects already being built, an approach the Trump administration tested out in April by freezing New York’s Empire Wind installation, though construction was already underway. President Donald Trump reversed that decision after a month, but the move signaled that opposition groups have gained traction.

“They are clearly feeling emboldened by Donald Trump,” said J. Timmons Roberts, a professor of environmental studies and sociology at Brown University, who studies networks of anti-wind activists. “They are taking these local victories on the East Coast and continuing to move along.”

Both CFACT and the California community group, Responsible Energy Adaptation for California’s Transition (REACT) Alliance, are part of the National Offshore Wind Opposition Alliance, a coalition formed last year to broaden the fight against offshore wind, which had previously played out mostly at the local level.

The Humboldt project was awarded the DOT grant in January 2024 and a developer has not yet been announced, but it’s been five years in the making. Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation, and Conservation District has already used nearly $20 million in state and federal funds to design and permit much of the planned wharf. The federal grant includes additional funds for port expansion as well as environmental restoration, a solar array, trails, public kayaking access, and a fishing pier.

Earlier this month, CFACT and REACT Alliance sent a letter to DOT Secretary Sean Duffy challenging the project’s “public interest” grant requirement, citing the “lack of viability of the floating offshore wind ‘industry.’” The letter also points to Trump’s anti-wind directive, which halted federal permitting and leasing for wind projects but did not mention grants for supporting wind infrastructure, like ports.

“We decided that the timing and the political will was there for us to go ahead and write this letter and to ask for the grant to be terminated,” said Mandy Davis, REACT Alliance’s president.

Davis told Canary Media that two recent setbacks in Maine’s pursuit of floating offshore wind motivated the group to act. First, Maine’s application for the same DOT grant awarded to the Humboldt Bay Harbor project was rejected in October. Those funds would have helped finance a port for floating offshore wind on Sears Island, Maine. Secondly, this spring, the Department of Energy clawed back a grant to the University of Maine to build and test the state’s first floating turbines.

Davis leads both REACT Alliance and the National Offshore Wind Opposition Alliance. She insists that neither of those groups receive any monetary support from CFACT, though the D.C. think tank co-signed the letter. According to the research group DeSmog, CFACT has received hundreds of thousands of dollars from fossil-fuel groups over the years.

“CFACT has, for decades, been undermining the science of climate change and attacking efforts to address the issue. This is just their latest effort to destroy a climate solution,” said Roberts.

This week, Senate Republicans joined their House colleagues in proposing to curtail a slew of clean energy incentives. Losing those could upend many a clean energy business, but the cuts would drive a dagger through the heart of the burgeoning green hydrogen sector in particular.

The Senate and House still need to agree on the final text of the bill, but both chambers would take a decade of incentives meant to incubate green hydrogen production and end them after this year. The truth is, though, even before Republican lawmakers sharpened their knives for the tax credit, the much-anticipated green hydrogen boom had quietly collapsed.

Just a few years ago, green hydrogen developers were planning to invest billions of dollars to build gigawatts of wind and solar capacity in prime locations from the Gulf to the desert Southwest, then funnel that electricity into huge banks of electrolyzers. These devices zap water and deliver pure hydrogen gas without the carbon dioxide released by conventional hydrogen production. Ambitious dreamers even proposed billion-dollar pipelines to carry the gas across Texas to ports on the Gulf, where it could be shipped to buyers in Europe and Asia.

I caught a bit of hydrogen fever myself during a reporting trip along the Gulf Coast in December 2023.

In Mississippi, leaders from a company called Hy Stor Energy showed me a vast sandy tract, framed by mastlike pines, where they intended to build a clean industrial park powered by gigawatts of off-grid wind and solar. These power plants would electrolyze hydrogen, which Hy Stor would stash in enormous subterranean storage tanks carved from the region’s salt dome formations. Then steelmakers and chemicals companies would flock there for an uninterrupted supply of undeniably clean hydrogen.

Sure, it sounded bold, but not impossible: Hy Stor’s then-CEO Laura Luce had previously developed salt dome storage for natural gas, and elsewhere in the region, salt dome tanks already store hydrogen molecules for the Gulf petrochemical corridor.

By October 2024, though, Hy Stor had canceled a contract to buy over 1 gigawatt of alkaline electrolyzers from Norwegian cleantech company Nel, and the company’s leadership had moved on, per their LinkedIn pages. (When I texted a former Hy Stor leader to request comment for this story, the phone number’s new owner told me they had nothing to do with the company. A few days later, they texted me again asking if I could give them $20.)

Other firms have canceled projects partway through construction, are holding off on final investments, or have found new customers for their renewables. A few green hydrogen projects are still moving forward, but they’re either in jeopardy, heading overseas, or far more modest than the gigawatt-scale ventures recently under development.

“I think it is overstating it to say [green hydrogen] is dead,” said Sheldon Kimber, whose firm Intersect Power spent years developing ideal wind and solar sites for hydrogen production, before pivoting to supply clean energy to data centers. But, he added, projects that get built in the next few years are likely to rank in the tens of megawatts, not the thousands, and focus on “small-volume, high-margin markets.”

Plug Power stands out as the rare company still building substantial non-fossil-fueled hydrogen production in the U.S. It recently finished a site in St. Gabriel, Louisiana, that can liquefy 15 metric tons of hydrogen daily, bringing its total production capacity to 40 metric tons per day. The company claims it runs the largest liquid-hydrogen production fleet in the nation.

Plug, however, serves as an inauspicious standard bearer for the U.S. green hydrogen industry. The 28-year-old company reported an accumulated deficit of $6.8 billion as of late March, meaning its cumulative losses outweigh any profits by that hefty amount. In February 2021, CEO Andy Marsh raised a warchest of $5 billion to build 500 metric tons per day of green hydrogen production by 2025; the stock traded above $60 a share at that time. Plug burned through that cash and completed just a sliver of the production goal. Currently, its stock trades at just over $1. (A company spokesperson did not respond to requests for comment.)

Plug Power and other hydrogen developers attracted billions of dollars from investors on the promise that success was just around the corner. Now, though, the hydrogen build-out has collapsed under the weight of several interlocking burdens. Self-defeatingly slow federal rulemaking on tax credits, soaring production costs, a dearth of major industrial buyers, and AI’s insatiable demand for power hobbled green hydrogen construction well before the Trump administration decided to go for the jugular.

The late 2010s were a euphoric time for clean energy developers. Renewables construction shot forward despite President Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign vows to bring back coal. Low interest rates paired nicely with the low but predictable returns that renewables projects could generate. Entrepreneurs imagined ways to capitalize on the imminent abundance of clean electricity by converting it into hydrogen.

The Covid-19 pandemic slowed the pace of activity, but then the Biden administration passed the 2021 infrastructure law, which designated $7 billion for a series of “hydrogen hubs” around the country. The administration chased that with the Inflation Reduction Act, which included a lucrative credit for the production of clean hydrogen, up to $3 per kilogram. A new multibillion-dollar industry was in the offing, and visionaries prepared to make their moves, as soon as the Internal Revenue Service published its guidance on how to claim that credit.

Then they waited. And waited.

“At $3 per kilogram, if your plant did not qualify for that and your neighbor’s plant did, then you’re out of business,” said Brenor Brophy, who ran development for Plug Power’s hydrogen production business in the early 2020s (he is no longer with the company). But there was no airtight way of ensuring one’s project would qualify until the final rule came out.

“The Treasury Department sat on that for two and a half years,” which was worse for the industry than if the credit were never created, Brophy added.

Paralysis seized the whole supply chain. Savvy suppliers chose a wait-and-see approach. This saved them money, at the expense of the communities they had promised to invest in.

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D), for instance, famously flew to Oslo to close a deal with Norwegian electrolyzer company Nel. That firm planned to invest $400 million to build a factory near Detroit, and gain $16 million in state funds for creating some 500 jobs. Nel has declined to make a final investment decision on the site. Despite that display of financial discipline, its stock was trading for pennies at the time of writing.

Plug Power, not afraid to be early to the party, went ahead and built a factory in Rochester, New York, in 2021 capable of fabricating 1.5 gigawatts of electrolyzers per year. That’s a big swing compared to today’s demand: Plug noted its Georgia plant, which it called “the largest liquid green hydrogen plant in the U.S. market” in January 2024, contains 40 megawatts of electrolyzers.

Biden’s Treasury Department didn’t release final guidance until days before Donald Trump moved into the White House. The new administration promptly held back funds appropriated by Congress for clean energy efforts and then set about dismantling the clean energy tax credit regime.

“Most of the pipeline will get abandoned if they cannot get a $3/kg subsidy,” said BloombergNEF analyst Xiaoting Wang. Some developers have put on a brave face and said they’ll plow ahead even without the tax credit, but she suspects such assertions are “more advertisement than a real business decision.”

Many of the planned hydrogen projects would have enriched solidly Republican districts, like Texas and Louisiana, the locus of legacy hydrogen production for petrochemical refining. But the prospect of self-inflicted economic pain has proven less of a deterrent for Republican lawmakers than industry insiders had hoped.

Project cancellations have continued amid the uncertainty. Major legacy hydrogen producer Air Products was supposed to build a $500 million green hydrogen production plant in Massena, in upstate New York. The company had cleared the 85-acre site and laid foundations to support 35 metric tons per day of green hydrogen electrolysis, per reporting by local outlet North Country Now.

But new CEO Eduardo Menezes took office in February, after an activist investor attacked the company’s green hydrogen strategy. Menezes promptly canceled Massena and a few other projects, incurring a cost of $3.1 billion for breaking contracts and writing down asset value. Burning that cash seemed preferable to actually finishing and operating those projects.

“Treasury was so effective at destroying the industry that it kind of seems malicious,” Brophy said.

Scaling breakthrough technologies requires faith that costs will fall and customers will want to buy. Elon Musk bet on that happening for electric cars, long before they were widely available to consumers. Solar evangelists dismissed predictions that their technology would never go anywhere; now solar is the fastest-growing new source of electricity production in the U.S. and the world.

Similarly, in that bright period before Biden-era inflation set in, hydrogen boosters saw a clear path to achieving cost declines akin to what solar and batteries had achieved. Legacy dirty hydrogen could be made for about $1 per kilogram; the green stuff cost several dollars more. But a technological learning curve could close that gap, the thinking went, and sway large industrial buyers. In 2021, the Biden Department of Energy set a goal to get green hydrogen costs down to $1 per kilogram within a decade.

Unfortunately, the cost declines that experts expected in the early 2020s never materialized. A late-2024 DOE report on clean hydrogen commercialization noted that costs had gone up, not down, by $2 to $3 per kilogram since its March 2023 analysis. The report cites higher real-world installation costs, rising interest rates, and escalating prices for clean power to meet the IRS requirements for the tax credit.

BloombergNEF analysts looked back at real-world installation costs for electrolysis plants built in 2023, and found they were 55% higher in the U.S. and Europe than the firm had predicted in 2022. Earlier estimates had assumed the core electrolysis equipment would drive most of the cost, but in practice, the seemingly incidental factors — like utility and contractor management, and contingency planning — inflated project costs considerably, Wang noted.

Researcher Joe Romm oversaw hydrogen efforts at the DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy in the 1990s, and subsequently published a book-length critique, “The Hype About Hydrogen.” He reissued it this spring, just in time for the latest cycle of boom and bust.

“Electrolyzers aren’t like photovoltaic cells or battery cells,” he told me recently. “There’s no ‘then a miracle occurs’ thing. … If there was going to be a learning curve, we never got there.”

Solar panels and battery cells are identical units that get mass-produced economically. Electrolyzer systems require more hands-on and bespoke installation work, with pipes and pumps and compressors and water tanks.

The other problem with analogizing green hydrogen to wind, solar, and batteries is a key difference in their uses. The latter group delivers electricity, which is distributed and used across modern society. But clean hydrogen requires highly specialized infrastructure to transport and utilize the famously flighty molecule.

“Someone’s going to have to take a big gamble, and if they lose, they’re stuck with a stranded asset,” Romm noted. An electrolysis plant with no green hydrogen customers can’t do anything else. And would-be producers struggled to find any committed customers.

Michael Cembalest, chairman of market and investment strategy for J.P. Morgan Asset and Wealth Management, tallied the missing demand to damning effect in his annual global energy-market report from March (see slide 46). He calculated that only 1% of green hydrogen projects slated for completion by 2030 have a binding offtake agreement.

That’s not to say developers were crazy for trying. A few years ago, major companies in Asia and Europe seemed eager to purchase large volumes of green hydrogen for their decarbonization plans, said Kimber, from Intersect Power. Such high-volume deals were vital for justifying construction of gigawatt-scale electrolysis projects in the sunny, windy sites of the American West.

“We had plenty of negotiations for gigawatt and multi-gigawatt-scale hydrogen, but most of them were with European and Asian customers, and most of those folks have backed away from the table,” Kimber said. “Without that policy certainty, no large oil company, steel company, power company is going to move ahead purchasing green molecules globally.”

Lacking that kind of anchor customer, a developer can’t justify building big or financing a whole pipeline to market — the billion-dollar gigaprojects depend on high utilization to make any financial sense, Kimber noted. They’re not something you can build and then wait a few years for demand to materialize.

Electrolysis devours electricity, which is fine in a world of cheap and abundant power. But, suddenly, any fledgling hydrogen project has to compete with much better-funded rivals in electric gluttony: AI computing hubs.

The business calculus of clean hydrogen necessitated driving down energy costs as much as possible to compete with cheap dirty hydrogen. For green hydrogen ventures to succeed, they would need to render their product a cheap commodity.

AI customers, on the other hand, are flush with cash and willing to pay top dollar to anyone who could deliver them gobs of power as soon as possible.

“When you enable a more valuable product, the total pie of value for the supply chain to carve up is greater,” Kimber said. “That makes the whole process of dealing with your customer and your vendors and everybody just less of a fight to the death. Everybody can truly be focused on, how do we scale this industry?”

For clean energy developers like Intersect, then, the choice to swap customers was uncomplicated. They had scouted the most energy-rich acreage they could find, but the big buyers for green hydrogen never showed up, and suddenly the wealthiest tech companies in the world wanted to sign deals ASAP.

“We were never a hydrogen company,” Kimber said. “We have been, are, and will be a company that is focused on finding ways to use the massive surpluses of all forms of energy that exist in places like West Texas, the panhandle of Texas, to power new industrial loads.”

“Now, it’s very easy for us to pivot into data centers,” he continued. “We’re negotiating AI data centers on all of our large [hydrogen] projects right now.”

Plug Power CEO Marsh opened a quarterly earnings call in May by going on defense about the tax credit revisions proposed by congressional Republicans.

“My first reaction was, we’re going to have to work to start construction this year to make sure that that plant would qualify,” Marsh told investors, referencing a development in Texas.

Then, tellingly, he handed the mic to Chief Revenue Officer Jose Luis Crespo, who talked up the bounty awaiting across the Atlantic, saying “Europe today is the most dynamic electrolyzer market in the world.” The European Union’s binding hydrogen procurement rules will soon kick in, and electrolysis projects at the 100-megawatt scale are starting to move toward reality, he explained.

Instead of building gigawatts of electrolyzers in the U.S. to export hydrogen to Europe, investment might just flow there instead.

Other U.S. entrepreneurs hope to survive through a more targeted approach: building small but closer to customers. The U.S. already produces 10 million metric tons of hydrogen per year for industrial users; many of them are open to cleaner and cheaper options, said Matt McMonagle, founder and CEO of startup NovoHydrogen.

“There’s no pricing transparency in this market; it’s very opaque,” he said. “There’s no Henry Hub equivalent like there is for natural gas.”

Green electrolysis still can’t compete with the $1 per kilogram that it costs to make dirty hydrogen at huge petrochemical complexes with cheap natural gas. But companies that get smaller deliveries of super-cooled liquid hydrogen can pay anywhere from $5 to $50 per kilogram, depending on region and shipping distance, McMonagle explained.

“We try to focus on the ones where we can save the customer money,” he said, recalling prior experience selling solar and batteries to businesses that wanted to cut their utility bills. And, unlike so many giga-scale hydrogen projects, NovoHydrogen actually has signed offtake agreements. “There’s no project without a customer,” McMonagle noted.

Novo is developing 10-megawatt electrolyzer systems at customer sites, which can produce about 2 metric tons per day depending on uptime, McMonagle explained. These projects will hook up to the grid, drawing power via clean energy supply agreements from the local utility. By building on-site, Novo needn’t worry about constructing pipelines across hundreds of miles or driving a fleet of super-cold tanker trucks.

Novo’s bigger projects function more like community solar: They’re located off-site but still near customers. Novo intends to install 235 megawatts of solar production across 1,000 acres in Antelope Valley, at the outer reaches of Los Angeles County, and funnel that power into electrolysis. If it comes online as planned in 2028, this facility should make about 27 metric tons per day. That’s nothing close to the colossal projects other companies contemplated at the height of the boom times, but it’s still bigger than any single green hydrogen source in the U.S. today.

As McMonagle sees it, the lure of the $3-per-kilogram credit attracted maybe too much attention to hydrogen, beyond situations where it really makes sense.

“A lot of people may have been chasing a shiny object and didn’t understand the details,” McMonagle said. “Let’s burst the bubble. I don’t think that means green hydrogen as an industry is gone — it will play a fundamental role in certain use cases. Trying to do everything just invites criticism that’s frankly valid.”

Hydrogen’s critics have long insisted that it never made much sense, either as a decarbonization strategy or a moneymaking venture. They see the industry’s implosion as a chance to avoid plowing billions of dollars into a technological dead end. Many climate advocates have dismissed hydrogen as a guise for fossil-fuel interests to prolong the use of their planet-warming product; they won’t be shedding any tears now.

But for the contingent of hydrogen entrepreneurs who emerged from successful renewables firms, the sudden loss of momentum delivers a yearslong setback in efforts to clean up heavy-duty transport, steelmaking, and other industries that are hard to decarbonize, and a missed opportunity to head off the worst impacts of climate change.

“I worry we’ve lost a decade, and that was a decade we didn’t have,” said Brophy.

The sudden vaporization of the imagined green hydrogen economy may be the kind of healthy correction this market needed. Whichever hydrogen projects ultimately get built could prove more durable for having made it through the ringer after the days of easy money. But that’s paltry consolation for the townships and states that were promised billion-dollar projects and high-tech jobs within a couple years. Beyond the economic hit, the green hydrogen collapse removes a leading contender for cleaning up the most carbon-intensive industries — at least until the next hydrogen boom comes around.

Former Minnesota House Speaker Melissa Hortman is being remembered by advocates and lawmakers as one of the most important climate and clean energy leaders in the state’s history.

From the state’s trailblazing community solar program to the flurry of energy and environmental laws adopted during Democrats’ 2023 trifecta, Hortman had a hand in passing some of the country’s most ambitious, consequential state-level clean energy policy during her two-decade legislative career.

Hortman, who was a Democrat, and her husband Mark were shot and killed in their suburban Minneapolis home Saturday in what authorities say was a politically motivated assassination. The alleged gunman, Vance Boelter, is also charged with attempted murder for shooting Democratic Minnesota state Sen. John Hoffman and his wife Yvette.

Hortman, who was 55 years old, twice tried for a state House seat before finally winning in 2004. Moving through the ranks of House leadership, the attorney served as speaker pro tempore, deputy minority leader, and minority leader before becoming speaker in 2019 and serving in that role for three legislative sessions.

“Clean energy was her first love,” said Michael Noble, who worked with Hortman for more than 20 years during his time as executive director of the Minnesota-based clean-energy policy advocacy organization Fresh Energy. “She really mastered the details and dug deep into climate and clean energy.”

Hortman chaired the House Energy Policy Committee in 2013, a standout year for solar policy in which she helped pass legislation establishing one of the country’s first community solar programs, and also a law requiring utilities to obtain 1.5% of their electricity from solar by 2020, with a goal of 10% by 2030.

“That was the year we put solar on the map,” Noble said.

Community solar advocate John Farrell recalled answering Hortman’s questions in detail concerning the benefits and drawbacks of community solar during meetings. She was preparing to defend the bill and convince others, even Republicans, that it could be something they could support.

“She wasn’t going to tell them something untrue,” said Farrell, who directs the Energy Democracy Initiative at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, an advocacy group. “She was going to seek reasons why this policy might be something that they would care about or that it might align with their values.”

Nicole Rom, former executive director of the Minnesota-based youth climate advocacy group Climate Generation, said Hortman was committed to educating herself on climate issues. Hortman attended the United Nations’ Conference of the Parties (COP) climate conferences and was part of the University of Minnesota’s delegation at the 2015 Paris climate talks, where her vision for more ambitious state climate goals and policy may have begun to percolate, Rom said.

The result was the strong climate legislation Minnesota accomplished in 2023, Rom said.

“If she never served a day before or a day after the 2023 session, she would still go down in history as an incredible leader,” said Peter Wagenius, legislative and political director of the Sierra Club’s Minnesota chapter.

After Democrats won control of the state House, Senate, and governor’s office in the 2022 election, Hortman understood the trifecta was a rare opportunity that may not arise for another decade, he said.

The following year, Hortman combined her skills and experience as a legislator, committee chair, and political leader to push forward an agenda that would fundamentally transform clean energy and transportation in Minnesota while solidifying her reputation as one of the legislative body’s greatest leaders.

The session’s accomplishments included a state requirement of 100% carbon-free electricity by 2040, along with more than 70 other energy and environmental policy provisions that created a state green bank, funded renewable energy programs, supported sustainable building, and increased funding for transit. Other laws passed that year required the state to consider the climate impacts of transportation projects, provided electric vehicle rebates, revised the community solar program to focus on lower-income customers, and improved grid-interconnection bottlenecks.

When the trifecta arrived, she ensured her colleagues were “ready to move on a whole list of items in an unapologetic way,” Wagenius said. Hortman also practiced “intergenerational respect” by elevating and helping pass laws proposed by first- and second-term legislators, he said.

Democratic Rep. Patty Acomb said Hortman empowered others within the party, made legislators feel they were “like a team,” and had a habit of never taking credit for legislative success. “She shied away from that,” Acomb said.

Acomb, who began serving in 2019, became chair of the House Climate and Energy Finance and Policy Committee four years later. She credits Hortman with that opportunity and with making Minnesota a national leader in clean energy.

“In so many ways, she was a trailblazer,” she said.

Gregg Mast, executive director of the industry group Clean Energy Economy Minnesota, said Hortman followed up on the historic 2023 session with a 2024 legislative agenda that built upon the previous year’s success. The Legislature made the permitting process for energy projects less onerous while passing a handful of other measures promoting clean buildings and transportation.

“She knew that ultimately, to reach 100% clean energy by 2040, we actually needed to be putting steel in the ground and building these projects,” Mast said.

Ben Olson, legislative director for the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy, first met Hortman 20 years ago while lobbying for an environmental bill. He found her to be kind, witty, and pleasantly sarcastic, the kind of legislator who asked questions, closely listened to responses, and offered sage advice. “Everyone liked her, and she was close to everybody who had spent time with her,” he said.

Ellen Anderson, a former Democratic state senator and clean energy champion, remembered when Hortman asked if she could co-teach a course with her on climate change at the University of Minnesota in 2015. Hortman came prepared for classes with notebooks of data and information. “She was super organized,” Anderson said.

Rom thinks Hortman’s love for nature drove her climate and clean energy advocacy. The legislator loved hiking, biking, gardening, and other outdoor activities.

In a blog post for Climate Generation before attending the UN’s 2017 climate conference, Hortman wrote about the impact of climate change on trees and how she had planted nearly two dozen in her backyard to offset her family’s carbon emissions. It was a message not lost on her two children, Colin and Sophie, who suggested in a statement that people commemorate their parents by planting a tree, visiting a park or trail, petting a dog, and trying a new hobby.

“Hold your loved ones a little closer,” they wrote. “Love your neighbors. Treat each other with kindness and respect. The best way to honor our parents’ memory is to do something, whether big or small, to make our community just a little better for someone else.”