“As we mature towards the final investment decision, if the walk-away scenario is the economical, rational decision for us, then this remains a real scenario for us as an alternative to actually taking the final investment decision,” Chief Executive Mads Nipper said on an Aug. 30 call with investors.

Orsted shares fell 25% in the wake of the news.

Now, a top credit rating agency has cast further doubt on the company’s financial future. Moody’s Investors Service downgraded its outlook for Orsted from “stable” to “negative,” according to a Sept. 5 report.

“Whereas the impairments don’t change the company’s [earnings] guidance or expected investment levels in 2023, Moody’s expects the headwinds that Orsted is currently facing in the US to lead to its credit metrics being weakly positioned at least until the end of 2025,” the credit rating agency stated in its report.

Moody’s affirmed Orsted’s existing bond and credit ratings, but also warned of “downward pressure” on its future ratings if delays and cost overruns worsen.

Stephanie Francoeur, a spokesperson for Orsted, pointed to the affirmation of existing credit ratings, rather than the outlook downgrade, in an email on Friday.

“Ørsted is rated by the three rating agencies, Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch, and all three rating agencies have confirmed our current rating,” Francoeur said. “We note that Moody’s continues to have confidence in our commitment to our current rating, and we’ll ensure that we deliver on our financial plan to provide Moody’s the comfort needed to continue its confirmation of our current rating.”

Orsted is hardly the first offshore wind developer to run into economic headwinds. In neighboring Massachusetts, two companies – SouthCoast Wind Energy LLC and Avangrid Renewables – have canceled their power supply agreements with utility companies, saying the existing payments are too low given increases in their expenses.

Orsted insisted as recently as June that it had no plans to renege on its electricity agreements with Rhode Island. The existing, 2019 agreement inked with the-utility operator National Grid gives the developer 9.84 cents per kilowatt-hour for 400-megawatts of electricity from the offshore wind facility over the entire 20-year contract. National Grid in turn would earn $4.6 million in renewable energy credits sold from the project.

In its August announcement, Orsted executives pledged to secure final investments in its projects, including Revolution Wind, no later than early 2024.

“The US offshore wind market remains attractive in the long term,” David Hardy, executive vice president and CEO of Region Americas at Ørsted, said in a statement. “We will continue to work with our stakeholders to explore all options to improve our near-term projects.”

State officials, including Gov. Dan McKee, have repeatedly stressed the importance of the offshore wind industry to the state economy, creating jobs and boosting state GDP.

Olivia DaRocha, a spokesperson for McKee’s office, said in an email Friday that Orsted assured the state of its commitment to the Revolution Wind project despite its recently announced financial woes.

“The company communicated that there are no direct impacts on the RI Revolution wind project and associated work, which is scheduled to start over the next several months,” DaRocha said.

DaRocha referred additional questions to Orsted.

Onshore construction work related to the 700-megawatt Revolution Wind project has already begun, with construction offshore expected to ramp up in 2024 ahead of a 2025 operational date, the company said previously. The 65-turbine wind farm planned off Block Island’s coastline has already secured approval from state coastal regulators, as well as a final environmental assessment from the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

In preparation for Revolution Wind and other projects in nearby waters, Orsted has committed $40 million into infrastructure investments at Quonset and Providence ports, including a wind turbine manufacturing facility at ProvPort. It has also partnered with local shipyards to build crew transfer vessels and invested $1 million into a training program for industry workers at Community College of Rhode Island.

Reprinted from E&E News with permission from POLITICO, LLC. Copyright 2023. E&E News provides essential news for energy and environment professionals.

For years, Delaware has been on the sidelines as the emerging offshore wind industry flocked to neighboring states, but a new law could transform the industry in the state — if it’s not too late.

Delaware’s Democratic-led Legislature recently ordered a study of the state’s offshore wind potential to be reported back by the end of the year. The move, which was signed by Gov. John Carney (D) this month, adds momentum for the state to set its first target for offshore wind, a goal of many lawmakers and environmental groups.

“We’re alone among our neighbors of not really having wind targets,” said state Sen. Stephanie Hansen (D), who has spearheaded the state’s reassessments of offshore wind to meet its climate targets as chair of the state Senate Environment and Energy Committee. “Delaware, as of now, I think, is really firing on all cylinders to move into the next phase of energy planning and implementation.”

If the study leads to a state offshore wind goal, it would bring Delaware in line with neighboring states and give it an opportunity to compete for industry jobs and businesses emerging along the East Coast. Power grid operator PJM Interconnection LLC is assisting with the study in looking at transmission impacts. But concerns about the cost of offshore wind still linger from a 2018 analysis that effectively tabled wind ambitions in the state for years.

Meanwhile, a movement against offshore wind along coastal communities has begun to capture the sentiment of Delaware towns and some lawmakers.

“I think it is harmful,” said state Sen. Bryant Richardson (R), the only senator to vote against Hansen’s study. He opposes the offshore wind industry due to its potential costs and what he says are negative impacts to the ocean environment and views from the shore.

“It’s an eyesore,” he said of the industry.

Delaware is juggling its offshore wind future as the industry reaches a turning point in the U.S.

Thousands of turbines are expected to go up in the northeast Atlantic in the coming years, spurred by state commitments and subsidies from Maine to Virginia. That comes alongside millions of dollars of promised state and private investments to beef up aging ports, build manufacturing and steel fabrication facilities, and make job programs to create a workforce capable of building and maintaining the new industry.

The wave of new proposals is partly thanks to the Biden administration’s commitment to raise enough wind farms in the ocean to power 10 million homes by 2030. The White House on Tuesday approved the nation’s fourth commercial-scale offshore wind farm off the coast of Rhode Island and has said it remains “on track” to reach 16 offshore wind environmental reviews by 2025.

The administration also announced last month potential new lease areas in the central Atlantic, including a swath of ocean about 30 miles off the coast of Delaware Bay. If developed, that area would add to two planned offshore wind farms that sit off the Delaware coast in federal waters.

Delaware’s grid may not reap the power of those two offshore wind projects, which are helping Maryland meet its offshore wind target. But experts say the new offshore wind areas could offer electricity to help Delaware reach its renewable portfolio standard of 40 percent renewable power by 2035.

Chelsea Jean-Michel, a wind analyst at BloombergNEF, said local opposition and limited space has made it difficult for the state to grow its renewable sector onshore, making offshore more attractive.

“Offshore wind projects can help decarbonize Delaware’s energy system by providing bulk renewable energy capacity in one go,” she said in an email.

For years, Delaware has flirted with the idea of offshore wind to help it decarbonize. It was poised to be the first U.S. state with an offshore wind farm when the proposed Bluewater Wind offshore wind project secured a long-term contract more than a decade ago with the state’s utility. The proposal later fell apart, largely because of cost concerns and investment uncertainty amid the recession.

Offshore wind got a second look largely thanks to Carney, who in 2017 ordered a study of the industry’s potential role in reaching state clean energy goals.

That analysis found that the cost of offshore wind energy would be high, prompting many lawmakers to shy away from supporting turbines off the coast.

One reason why offshore wind is getting another look in the state now is that costs have fallen significantly as projects have advanced in the U.S.

An updated report from Delaware’s Special Initiative on Offshore Wind (SIOW) last year found the cost of a Delaware offshore wind project — if it was large enough to capture economies of scale — would cost the same as existing sources of electricity in the state like natural gas and solar. That would be the case without state subsidies or tax breaks, researchers said. The study considered federal incentives that were expanded in the Inflation Reduction Act giving developers a 30 percent tax credit for offshore wind.

“There’s enough time, plenty enough time, for Delaware to do one project, maybe two, and still get advantage of that tax credit,” said Willett Kempton, a professor at the University of Delaware’s School of Marine Science and Policy and a leader of SIOW.

Kempton’s report also weighed how fossil fuels negatively impact human health and the environment, driving up the overall cost of using those sources for power. When those factors were considered, offshore wind became cheaper than existing sources like natural gas in the study’s models.

Hansen said Delaware hired analysts to interpret the report. When executive action did not occur, she said she wrote the legislation that passed earlier this year tasking the governor’s office and state regulators to review and report back to the Legislature on offshore wind’s potential.

“We need to hear from the administration on this, is this a direction that we ought to go?” she said. “I can tell you that there is the legislative will to move this forward. But we also aren’t experts.”

Carney’s office declined to comment for this story.

Hansen said that Delaware’s tardiness on offshore wind could lead it to lose out on benefits from the industry, such as jobs and manufacturing.

Jean-Michel, with BloombergNEF, noted wind developers have forged relationships with nearby state lawmakers that give those states an advantage.

“Given that it’s entering the market later and it is likely to be a smaller market, Delaware may not benefit as much economically through offshore wind in terms of green growth or jobs, or it may have to pay a significant premium for offshore wind projects if it wants to stimulate that local manufacturing sector,” she said.

However, Kempton, with the University of Delaware, said he would warn lawmakers, if they proceed with a procurement target in Delaware, against tying offshore wind projects to local investment.

Other states have encouraged offshore wind developers to bundle economic development plans into their wind proposals, leading to manufacturing projects planned in states like New York and Maryland.

But those investments mean the price of electricity for those projects is higher, Kempton said, noting that wind developers may not be the most effective planners for associated supply-chain businesses. They also may not have long-term commitments for jobs in mind onshore.

Offshore wind supporters are hoping when the Delaware Legislature meets again in January, lawmakers will have offshore wind on their minds.

Hansen said she couldn’t disclose some of the conversations happening now on offshore wind but that Delaware leaders could make progress even before the session convenes.

But as the state weighs a greater role for offshore wind, industry opponents may also be growing.

It’s a pattern that has played out in other coastal states as offshore wind proposals draw pushback from beachfront homeowners who don’t want steel marring their ocean views and town councils concerned the industry could hurt tourism. Conservative groups such as the Delaware-based Caesar Rodney Institute also are supporting the opposition movement.

Richardson, the Delaware Republican, said he’s been reading material put out by the institute on offshore wind and connecting with opponents who share his skepticism about the industry, its costs and its impacts.

“I hope it will fail,” he said of the state’s plan on offshore wind.

This story was originally published on Jan. 19 by THE CITY. Sign up here to get the latest stories from THE CITY delivered to you each morning.

For Tawanna Davis, winter means hauling out an electric space heater to keep warm when her Bronx building’s heat is insufficient.

Davis, 51, has for two decades been a resident of Twin Parks Tower North West in Fordham Heights, the site of a deadly fire earlier this month that officials have said was sparked by a malfunctioning space heater.

“You get the ice on the inside [of the window] and everything,” Davis told THE CITY. “It be really, really cold in your apartment.”

While some tenants said they’d be shivering without space heaters, others said they had to open their windows in the winter when their units became unbearably warm.

That hot-and-cold situation, which many New York apartment dwellers know all too well, highlights the importance of improving energy efficiency in residential buildings.

And this can be especially true for subsidized, income-restricted complexes — aka “affordable housing” — where improved comfort and safety are immediate benefits beyond slashed greenhouse gas emissions.

But upgrading affordable housing stock at the necessary pace presents logistical and financial challenges, which the administrations of New York City Mayor Eric Adams and Gov. Kathy Hochul need to solve regardless in order to achieve their climate goals.

The Twin Park Towers, built in 1972, are part of the state’s Mitchell-Lama housing program and receive some funding through the federal Section 8 program, which helps subsidize rents for low-income tenants.

“The fact that a relatively new building by New York standards has people living in situations requiring space heaters in order to reach a level of comfort suggests the complexity of this issue,” said Jonathan Meyers, a partner at HR&A Advisors, a firm that consults on real estate strategy and policy in New York and around the country.

“It’s a very stark reminder that there’s a fine line between inefficiency, which most of us can tolerate on a day-to-day basis, and tragedy, which is intolerable,” he added.

People working on the state’s decarbonization strategy, born out of New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act of 2019, say improvements in building energy efficiency aren’t just ways to mitigate climate change and get off of fossil fuels.

The green push, they say, can also lead to immediate health benefits: Properly insulating windows, for example, can ensure consistent temperatures in all seasons, and installing electric heat pumps can also help cool air. Both are useful to combat deadly extreme heat in the summer and illness-inducing chills in the winter.

“In terms of ever-increasing incidences of extreme-weather events, energy efficiency is going to play a bigger, maybe even life-saving, role,” said Eddie Bautista, director of the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance and part of the group that advises the state’s Climate Action Council.

On Tuesday, as if to further demonstrate the myriad dangers of fossil fuels, an apparent gas explosion rocked a residential building in Longwood, just a few miles south of Twin Parks. The blast killed one person and injured several others, officials said. Adjacent buildings were ruined in the ensuing fire, and the Fire Department is still investigating the exact cause.

The incident showcases the importance of phasing off gas and oil, not only to avoid carbon emissions, but to increase safety, environmental advocates note.

Gov. Kathy Hochul included in her budget plan this week a proposal to ban gas hookups in new buildings across the state by 2027, echoing a city law signed in recent weeks. Environmentalists say the governor’s timeline is not quick enough, and some asked for more funding to electrify existing housing.

“Thousands of New Yorkers are already dying premature deaths every year because of the fossil fuels we’re burning in our homes, and every once in a while, it’s not a slow, premature death thing — your house literally explodes,” said Alex Beauchamp, northeast regional director of the nonprofit Food and Water Watch. “We have to move much faster, not only for new buildings, but for existing ones as well.”

As part of the budget, Hochul also proposed a five-year, $25 billion housing plan that would in part cover efforts to weatherize and electrify New York’s housing stock. Her State of the State proposal earlier in the month cited projects to encourage electric, high-performance heating equipment and renovating buildings to keep temperatures consistent “to reduce the need for space heating and air conditioning,” among other reasons.

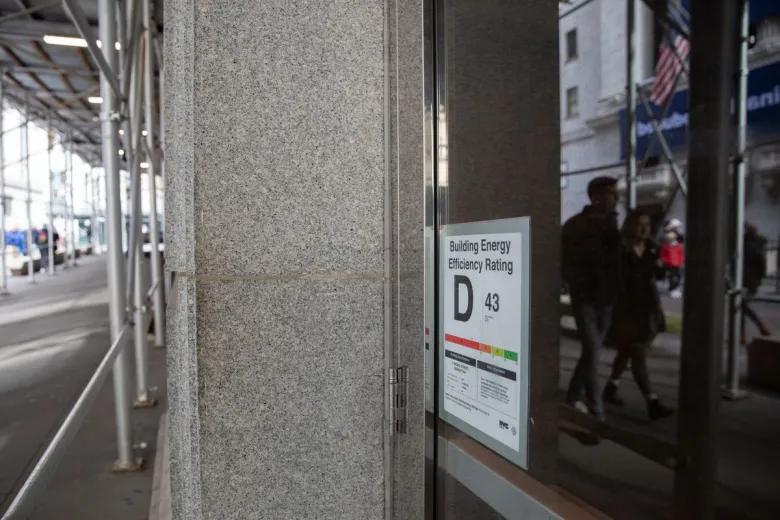

For over a decade, building owners in New York City have been required to tally their water and energy consumption data each year and submit the information to the city. Based on that, they get a grade. A 2019 law required landlords to make their efficiency grade public.

Twin Parks, for a second year in a row, earned a D in 2021, the same as about half of all buildings in the Bronx. Citywide, 39% of all buildings earned Ds.

The building, which installed new gas-powered boilers in 2015, according to city records, faces similar challenges to improving its efficiency as many other older buildings. Its residents, like many others in the city, don’t have separate thermostats to control indoor temperatures in their units.

They also don’t have individual electric meters, like many affordable housing buildings, meaning that they are not encouraged to use less power — so a resident can run a space heater all day and even open windows while doing so without thinking about the bill.

A spokesperson for the Twin Parks owners did not respond to requests for comment.

Landlords, who foot utility bills in the absence of what’s known as sub-metering, must themselves make improvements to reduce energy usage. Beyond money-saving potential, such capital upgrades focused on efficiency can result in healthier, more comfortable living quarters for residents.

Homes and Community Renewal, a state agency that develops and preserves affordable housing, considers energy efficiency for both new construction and preservation projects, a spokesperson said. It also requires private developers that work with the state to stick to efficient-design guidelines when applying for funding.

The problem lies in how to shore up enough funds to cover the scope of the efficiency-related work that must be done, while balancing the need to create and preserve affordable housing.

Housing dollars from the city, state and federal government are stretched “to the max,” said Lindsay Robbins, a senior advisor for building efficiency and decarbonization for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Many of the investments needed to improve existing subsidized affordable housing are identified when owners seek to refinance, which happens every 15 to 20 years, according to Robbin.

The city and state in 2017 developed an “integrated physical needs assessment” for properties, a tool which considers necessary capital improvements, like a roof replacement, along with an energy efficiency audit, among other measures.

“If we don’t make the most of that opportunity and ensure that building owners have resources and financing they need to really make these properties safe and healthy and efficient and electrified, that building’s probably not going to do diddly-squat for another 15 to 20 years,” Robbins said.

“We need to fundamentally rethink the kinds of public resources that we put into this … because putting people in quality and healthy housing — there’s nothing more important than that.”

Property owners can also apply for loans and grants through the city’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, and they may participate in a $24 million pilot run by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority and HPD that seeks to finance electrification and energy efficiency upgrades in about 1,200 units of housing.

Another $30 million in state funds are available for income-restricted buildings that are seven stories or shorter through the RetrofitNY program.

Rep. Ritchie Torres (D-The Bronx) on Friday urged for the passage of federal legislation that would include about $150 billion for housing investments, which, he said, could be used to “create, preserve and retrofit 1.4 million units of affordable housing.”

“Part of Build Back Better must be building back safer,” he told reporters at the scene of the inferno earlier this month. “The fire in Twin Parks North West must be seen in the context of historical disinvestment from affordable housing, from places like the South Bronx, from lowest income communities of color, and the Build Back Better Act presents a historic opportunity to reverse decades of disinvestment.”

In addition to more federal funds, Robbins also wants to see more private financing, grants and investments from the New York Green Bank, a state agency with the mission to “accelerate clean energy deployment.”

The financing challenge will come to a head with new Local Law 97, which sets greenhouse gas emissions caps for buildings over 25,000 square feet. Mitchell-Lama buildings like Twin Parks have a compliance date of 2035, while most buildings must emit below the specified targets starting in 2024.

Now it’s up to Mayor Eric Adams’ administration — with the help of an advisory board — to finalize the rules that govern the new law and figure out how to help property owners finance the upgrades necessary to achieve the emissions caps.

In the meantime, state Attorney General Letitia James said she intends to use the power of her office “to get to the bottom of this fire” as environmental advocates continue to sound the alarm that energy efficiency equals safety and justice.

“We can’t achieve a climate just society without centering BIPOC [Black, Indigenous and People of Color] and low-income communities,” said Daphany Sanchez, executive director of Kinetic Communities Consulting, a firm focusing on energy equity. “The fire that you saw in The Bronx is exactly the issue: the result of people ignoring climate, the result of people ignoring Black and brown communities.”

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news organization dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York

A St. Paul, Minnesota, college’s microgrid research center is preparing to expand after securing significant new state and federal funding.

The University of St. Thomas’ Center for Microgrid Research plans to triple its three-person staff and enroll more students thanks to money from a $7.5 million state legislative appropriation and $11 million in federal defense bill earmarks secured by U.S. Rep. Betty McCollum.

State officials who championed the funding said they hope the center’s education and research efforts can help train future grid technicians and smooth the state’s path to 100% clean electricity by 2040.

“We’re at a time of not only a great transition but of a great opportunity,” said state Sen. Nick Frentz, a Democrat from Mankato. “We’ll be looking at transmission, distributed generation and innovation as we transition, and funding for the St. Thomas microgrid research is a part of the state’s plan to lead.”

Microgrids are small, hyperlocal networks of electricity generation and storage systems that together can operate independently of the rest of the power grid. They’re often used by military, healthcare or research campuses that require a level of reliability greater than what the local utility can provide.

But they’re not just expensive backup power for wealthy institutions. Microgrids are also expected to play a role in the clean energy transition, helping to get the most value out of clean energy investments and connecting customers to one another in new ways.

“Microgrids are another opportunity for clean energy,” said John Farrell, co-director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance and director of the Energy Democracy Initiative.

Microgrids could help balance variable power sources such as wind and solar, helping to absorb and store surplus generation and share it with the grid later when it’s needed, Farrell explained. While microgrids can be powered by fossil fuel backup generators, they also can run on solar panels, whose value can be greater when they are networked with arrays on multiple sites.

The University of St. Thomas has been developing its campus microgrid for about a decade. Today, it consists of a 48-kilowatt rooftop solar array along with a diesel generator, a lead acid battery pack, and an inverter that converts direct current to alternating current. A campus substation connects to Xcel’s local grid.

Like most microgrids, the St. Thomas system can run in “island” mode, meaning it can operate even when the power grid fails by drawing on the battery, solar panels and backup generation.

The Center for Microgrid Research opened in 2020 as a way to build research and education programming around its campus microgrid. Mahmoud Kabalan, the center’s director, was hired in 2017 from Villanova University to teach engineering and helped secure seed funding from Xcel Energy’s Renewable Development Fund for the program.

Don Weinkauf, the school’s dean of engineering, said the new state and federal funding will allow the center to expand both the program and the microgrid system itself.

“This stuff is expensive,” Weinkauf said. “Each piece of equipment is on the scale of a million dollars, and right now, we are expanding to reach a 1-megawatt capacity.”

The center will have 10 full-time employees next year and be able to enroll up to 25 students. More staff and students will allow more collaboration with utilities, corporations, and fellow researchers. Within the next few years, the microgrid will connect to more than five buildings, including a new science, technology and arts center, dorms and a parking facility.

Kabalan said he expects more funding from the U.S. Department of Defense, which sees the program as a workforce training ground and source of applied research to help design, test and implement microgrid technologies.

“This funding will position the state and the nation to produce innovative engineers that can address the need for microgrids and distributed energy technologies,” Kabalan said. “A big part of what we do is educate and train engineers.”

The center is collaborating with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on a military initiative to install microgrids at every military base by 2035, Kabalan said. Research related to that project will be publicly available to other microgrid operators and researchers. Students and faculty have other clients and supporters, including utilities Xcel Energy and Connexus Energy.

Part of the center’s design and strategy has been to serve as a place where clients can test how their equipment works in a microgrid. The technology available includes test bays to plug in products, controllers, relayers and emulators capable of creating simulated environments.

“Interested parties can literally roll in their equipment and we can test their technology at full scale,” Weinkauf said. “This is an industry-friendly center that can help us, and the state of Minnesota, navigate our future grid.”

Students like the hands-on quality of the microgrid center. Engineering student Oreoluwa John Ero, a research assistant at the center, has helped develop models to attach the new STEAM building to the university’s microgrid.

“I like the ability to see and practice the different things you learn in school and the chance to learn while on the job,” Ero said.

Utility industry professionals who have visited the center also like the hands-on approach. Connexus Energy engineering and system operations director Jared Newton said the center “immediately resonated with me because I saw students learn on real-world equipment that we use. The problems they were trying to solve and the tools they were using were familiar.”

As climate change and aging infrastructure make weather-related power outages more common, Kabalan thinks microgrids will become more common for critical infrastructure such as hospitals, prisons, data centers, food storage areas, cooling centers and government facilities.

Ero sees how the microgrid could transform the power grid in the United States and in his home country of Nigeria, where electricity outages are common and can last for hours and weeks.

“It’s a technology that should be made available to people,” Ero said, “not just in Nigeria, but all over the world.”

A Minnesota gas utility says it is successfully blending “green” hydrogen into its natural gas pipeline system in one of the first such tests in the country.

Since last summer, CenterPoint Energy customers near downtown Minneapolis have been burning a bit of hydrogen alongside the usual mix of methane gas in their stoves and furnaces.

The utility completed a $2.5 million hydrogen production pilot facility last year and began injecting the carbon-free fuel into its system in small amounts in June. Hydrogen accounts for no more than 5% of the overall blend at any time.

“The good news is that this facility has integrated well with our distribution system,” CenterPoint spokesperson Ross Corson said of the facility’s first months of operation.

The pilot project is a chance for the utility to iron out operational challenges. It’s already made several adjustments, including changes to a water circulation system and the way in which it removes moisture before injecting the gas into its pipelines.

But even a technical success for the project is unlikely to resolve broader questions in Minnesota and beyond about the role of hydrogen in a clean energy economy. Some experts and climate advocates have argued that blending hydrogen into the natural gas system is an inefficient and expensive climate solution compared to switching to electric appliances, and that hydrogen should be reserved for industrial uses and other difficult-to-decarbonize sectors.

Most hydrogen today is produced from a chemical process involving fossil fuels that releases significant carbon emissions. “Green” hydrogen is produced by using electricity to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. If done with renewable electricity it can be a zero-emission fuel source.

“The color wheel of hydrogen is complex and a little bit overwhelming, but green hydrogen, as long as it’s generated using renewable electricity, is the gold standard,” said Joe Dammel, buildings program manager for the St. Paul clean energy advocacy group Fresh Energy, which publishes the Energy News Network.

CenterPoint’s small plant sits on the site of a former coal gasification plant that began operating when CenterPoint was called the Minneapolis Gas Light Company. The company chose the site due to its central location in its pipeline system and the availability of space. The grounds now host the green hydrogen center and a parking lot for workers taking courses across the street at a CenterPoint training center.

John Heer, the utility’s director of gas storage and supply planning, oversees the facility. Making green hydrogen is not a huge technical feat and involves electrolysis, Heer said.

City water is purified before being piped into a 1-megawatt electrolyzer that processes two gallons a minute. The facility disperses oxygen through fans outside the plant. “We’re learning by doing,” Heer said. “We need to know how it works before we can scale it in a larger facility.”

The facility gets electricity from Xcel Energy’s grid and offsets its electricity use with wind energy renewable credits, also purchased from Xcel. Critics have disputed whether hydrogen facilities that use renewable energy indirectly through offsets should qualify as “green.”

Part of the pilot is determining how hydrogen changes the characteristics of natural gas in pipelines. Hydrogen is less dense than methane and only carries about one-third as much energy per cubic foot. The molecules are the smallest in the universe and can exacerbate pipeline cracks and cause embrittlement, increasing leakage and explosion risks above certain concentrations, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

In July, a California Public Utilities Commission study found that 5% blends of hydrogen and natural gas are safe but going above that amount could require modifications to stoves and water heaters. Moreover, since green hydrogen carries less energy content, more of it would be required to replace natural gas, the report said.

Even if produced from fully renewable sources, hydrogen is unlikely to replace natural gas for various reasons, Dammel said. The manufacturing process absorbs more energy than it produces, with roughly a 30% to 35% loss. Larger green hydrogen plants will need to compete for clean electricity at a time when demand for wind and solar power has skyrocketed.

“We think that just adding hydrogen to the distribution system to substitute for fossil gas has economic and technical limitations,” Dammel said. “It’s not going to be a 100% substitute for every molecule of fossil gas that’s right now in the system.”

To replace all the nation’s natural gas consumption with green hydrogen would be an enormous undertaking, demanding hundreds of billions of dollars in investment in renewable energy, electrolysis technology, pipeline infrastructure and storage.

Critics also say green hydrogen production requires much water, a potential problem in more arid regions than Minnesota. Yet one study and market data suggest that its manufacture consumes far less water than plants using coal, nuclear, natural gas, biomass or solar.

For now, clean energy advocates believe the best application for green hydrogen will be heavy-duty industrial applications where using electricity cannot cost-effectively replace natural gas, Dammel said.

The biggest hydrogen markets currently are petroleum refiners, fertilizer companies, food processors and metals treatment firms. Hydrogen’s advocates, however, believe that in addition to manufacturing it can revolutionize the transportation sector.

Hydrogen is expected to get a boost in 2023 from the federal government. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, signed in 2021, includes $9.5 billion in incentives for clean hydrogen. The Department of Energy’s Hydrogen Shot program has set a goal of reducing the cost of 1 kilogram of hydrogen to $1 in one decade.

In September, the Energy Department released a 112-page clean hydrogen roadmap that calls for funding regional hydrogen hubs, support for manufacturing plants, and research into reducing the cost of electrolysis.

The Inflation Reduction Act includes a tax credit for green hydrogen that will soon provide up to $3 a kilogram credit for producers. The U.S. Treasury Department is expected to decide soon what criteria need to be met, with some environmental groups lobbying for on-site renewable generation to be a requirement.

“It costs more to produce hydrogen than to use natural gas today, so $3 a kilogram is kind of a big deal,” said Heer, the utility spokesperson. CenterPoint also wants to build a larger, second hydrogen plant but the timing on that has yet to be determined. The pilot is expected to avoid 1,200 tons of carbon emissions annually.

For decades, hydrogen has been touted as the fuel of tomorrow — a day yet to come.

But a $9.5 billion package wrapped into the enormous 2021 federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act could assure the element’s speedier arrival in an eco-friendlier fashion.

A bulk of the funding, $8 billion, would go toward constructing regional clean hydrogen hubs to connect production facilities, terminals and pipelines with users in the transportation and manufacturing sectors. West Virginia is vying for one hub.

The goal is to replace “dirty” hydrogen sourced from natural gas with “green” hydrogen generated by splitting water — H2O — with electrolysis technology.

Ideally, that separation would be powered with renewable energy, a boost for the Biden administration’s targets of a 100% clean electrical grid by 2035 and net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

Alleyn Harned was a proponent of hydrogen fuel long before he became the executive director of Virginia Clean Cities in 2011. He has been based in Harrisonburg since the organization formed a partnership with James Madison University in 2009.

In 2006, he coordinated a state working group that issued a public report about Virginia’s potential hydrogen economy. He also helped draft Virginia’s initial Energy Plan as the state assistant secretary of commerce and trade under Gov. Tim Kaine, now a U.S. senator.

“Green hydrogen is one of many options we have ahead of us to continue a path to better jobs and energy production in Virginia,” the 41-year-old said. Investing in it is more sensible “than blowing money on imported fuel that has energy security issues.”

Researchers see the promise of hydrogen in harder-to-electrify heavy industries such as steelmaking, and in the transport sector with maritime shipping, trucking and eventually aviation.

One urgent matter is dropping the price per kilogram of green hydrogen from the current $5-plus to $1 by 2031. Producing a kilogram of “dirty” hydrogen from methane is now a bargain at roughly $1.50.

Harned fully backs the quest for green hydrogen, but he isn’t such a purist that he wants to ban all methane as hydrogen feedstock. His instincts tell him that the perfect can’t be the enemy of the good when taming emissions of planet-warming gases.

“We are not going to eliminate every gram of carbon dioxide because that’s not the mission,” he noted. “The mission is to eliminate every net gram of carbon dioxide.

“Hydrogen is one scratch in the sand when we’re trying to move mountains.”

In this interview with the Energy News Network, Harned explains how green hydrogen can benefit Virginia’s economy and environment. His responses were lightly edited for clarity and length.

Q: What is the most significant accomplishment achieved by Virginia Clean Cities under your watch?

A: Our biggest accomplishment is raising awareness that transportation in Virginia is the economic sector with the largest greenhouse gas emissions. That information was withheld for years and it took time for people to understand what it meant.

Q: Green or clean hydrogen is having a moment in the headlines. Is it all hype or does the science back it up?

A: It’s understandable that people might think hydrogen is being overhyped. What’s positive is that we are seeing the federal government now investing in a massive research program with plans to build at least four hydrogen hubs nationwide and expand access to hydrogen fuel.

Keep in mind that hydrogen is emerging as part of a larger menu and would be part of a whole ecosystem of energy.

Energy is everything in our economy and hydrogen is an important upcoming component. But we don’t just snap our fingers and we’re done.

Q: U.S. Rep. Don Beyer, D-Virginia, is a co-sponsor of the Clean Hydrogen Production and Investment Tax Credit Act of 2021 (H.B. 5192). Why is Beyer supporting this and what is the measure’s intent?

A: Congressman Beyer represents an area in Northern Virginia that produces no oil. His family also has a long history operating auto dealerships, which perhaps explains his interest in transportation fuel.

His legislation offers what I would call a measured approach to support innovation in producing green hydrogen. That’s because it offers the highest tax incentives to production methods that reduce lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions most significantly. The top tier is a 95% reduction.

The legislation offers much lower incentives for other production methods that offer less of a lifecycle emissions reduction.

The type of tax credit laid out in H.B. 5192 showcases federal interest in reduced lifecycle greenhouse gases by putting a target on that figure.

Q: Let’s talk about green hydrogen in Virginia. First, are any universities or companies conducting research or using hydrogen of any type?

A: The U.S. Department of Energy spends millions every year on hydrogen research, so there could be projects going on in Virginia that I’m not aware of.

One piece of progress Virginia Clean Cities has made with James Madison University is to use federal funding to conduct the economic research behind what’s called the Hydrogen Fuel Cell Nexus.

Basically, the nexus is a U.S.-based business directory of hydrogen companies and products that buyers, partners, planners and other collaborators can use as a building blocks tool to put an actual project together, big or small.

Q: The Virginia General Assembly addressed passenger vehicles in 2021 by passing the Clean Cars law, which stimulates a transition to electric vehicles. But what about the separate carbon pollution from heavy-duty trucks and other segments of the transportation sector?

A: High-pressure hydrogen fueling infrastructure matters for these vehicles. That starts with fleet-fueling sites, shared fueling sites that can handle large vehicles, and a wide redundancy to the network.

It will take time but we see transit fleets installing their stations and succeeding with hydrogen today.

Consider that a tractor-trailer gets about 4 miles per gallon and emits 25 pounds of carbon dioxide per gallon of diesel. This is an opportunity for a higher density fuel like hydrogen, one that can produce zero tailpipe emissions.

Other mobile sources hydrogen can power are garbage trucks, transit vehicles, refrigerated trucks, as well as forklifts in all types of industries and marine ports with tractors and other vehicles.

Q: In-the-know observers predict that green hydrogen growth will take off in the 2030s. What kind of investments will that require?

A: Renewable hydrogen is produced at scale today and it’s a growing industry. There’s no need to wait until 2030. With energy hubs being built and with lessons learned from advances in California, those markets will only get bigger.

It’s what the whole country needs to thrive economically as we reach the end of our carbon budget. It’s a card that can be stored and played when needed.

Q: Relatedly, this country produces more than 10 million metric tons of non-green hydrogen, mostly from natural gas. That’s roughly 2% of U.S. total emissions. The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that producing an additional 10 million metric tons of green hydrogen would require doubling today’s wind and solar deployment. Is that buildout a pipe dream?

A: We will get this done, not because it’s easy but because we can and we have to so we can have a future. This transition is a critical component of maintaining our economy through the end of the century.

Everybody recognizes that our fossil fuel use will change dramatically in the decades ahead. It will be replaced with lower- and zero- and negative- carbon energies.

Q: On that last point you differ from strict adherents. They claim green hydrogen can only be created when renewable energy is used to generate the electricity that splits water into hydrogen and oxygen. Can you explain your reasoning on methane-sourced hydrogen?

A: I’m neutral on the pathway to decarbonization. It’s a game of inches, not a game of magic beans.

Capturing hydrogen via electrolysis (splitting water molecules) certainly works. But being able to eliminate releases of waste methane from landfills, wastewater treatment plants and agriculture using a process called steam reformation is crucial when you consider that we need to address this area of harmful waste and emissions.

Studies by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality estimate that annually, our landfill methane is the equivalent of 2.4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, manure management is half a million metric tons and wastewater is 0.7 million metric tons. It could be a win to grab it, reform it and reuse it.

Q: Environmental organizations such as the Natural Resources Defense Council have pointed out that “hydrogen leakage” has potentially negative climate consequences. Can that be mitigated?

A: Hydrogen safety and leakage is a top-level area of action for regulators and manufacturers. They’re not going out there building anything helter-skelter. Systems will be built with numerous layers of leak prevention.

Yes, it’s likely there will be minimal leaks so reducing that is important. But think about it this way: To get emissions equivalent to the carbon pollution from burning one gallon of gasoline, you would have to leak 2.5 kilograms of hydrogen into the air. It’s unlikely that a fraction of that hydrogen will be released, so it paints a rosy picture for the reduction of emissions.

Q: If green hydrogen isn’t generated directly on-site, how will it be shipped? Is talk about repurposing natural gas pipelines realistic?

A: It’s unlikely existing infrastructure such as large pipelines would be used. Hydrogen can be moved as a liquid or as a gas in a high-pressure cylinder. It’s possible it could be put into newly designed pipelines.

In Virginia, you already see heavy trucks and tanker trucks carrying large amounts on roadways. Also, Roberts Oxygen and other companies use smaller trucks to transport portable canisters for individual projects.

There is flexibility in all of this and distribution will be well-regulated.

As hydrogen is a bottle of energy, it seems like a good idea to distribute production all over Virginia to maximize local access and jobs.

Q: Anything else?

A: With transportation, it’s not easy to transition to hydrogen so it will take a little time. That’s why I’m excited that we’ve arranged a fleet demonstration for rural Virginia of a hydrogen vehicle from Toyota called the Mirai. We will make it available to government and rural fleet users periodically in 2022 and 2023. This totally hydrogen sedan is available in California and is used by federal fleet vehicles in Washington, D.C.

Illinois business leaders and researchers are hoping to leverage hundreds of millions of federal dollars to develop a thriving “hydrogen economy.”

The vision involves using the state’s plentiful nuclear power and renewable energy to separate hydrogen from water, and then using the resulting fuel to power industrial processes and heavy-duty vehicles.

The Midwest Alliance for Clean Hydrogen, or MachH2, is among more than 30 contenders seeking funding from a $7 billion U.S. Department of Energy program to jumpstart six to 10 regional hydrogen hubs across the country. Each will be aimed at producing and distributing pure hydrogen that is thus far in short supply.

The coalition behind the Illinois bid includes universities, utilities, economic development agencies, manufacturers, Argonne National Laboratory, and power producers like Constellation Energy and Invenergy, which has launched its own pilot program producing hydrogen in Illinois.

Jon Horek, director of hydrogen project development for Invenergy, said the federal funding can hopefully help solve the “chicken-and-egg problem” of developing hydrogen “demand and supply at the same time — production and consumption at the same time.”

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, and some see it as key to a clean energy transition, capable of replacing fossil fuels in vehicles and industry. But just getting pure hydrogen to users and fueling stations is a challenge; hydrogen occurs only in tiny quantities naturally in its purified form.

Currently, most hydrogen used industrially is purified or produced on-site, and hydrogen fueling stations for transportation are not common. But backers of the hub hope to change that, with hydrogen producers and hydrogen pipelines connecting entities stretching from northern Wisconsin south through Illinois, Missouri and Kentucky, and east to Ohio and Michigan.

MachH2 was one of 33 proposals to receive official encouragement to move forward from the Department of Energy, out of 79 applications submitted. A final proposal is due in April. The program was created by the Infrastructure Investment Act.

Jay Walsh, vice president for economic development and innovation for the University of Illinois system, said the Midwest and Illinois especially are ideal locations for a hydrogen hub, given the robust transportation and manufacturing infrastructure and academic resources.

“There’s distribution infrastructure — we’re located at the crossroads of the U.S.,” Walsh said. “Transportation is an important sector to decarbonize, and we’re good at transportation: water, rail, air, and of course trucking. We have all of those components, and add on top of that the talent and ability to create the talent — the workforce development.”

Currently most of the hydrogen used in fuel cells or industry is created by splitting hydrogen in methane (CH4) away from the carbon, usually using steam — which creates carbon dioxide as a byproduct — or energy-intensive pyrolysis, which creates pure carbon.

A cleaner way to produce hydrogen is from water, with a process known as electrolysis. But that also takes electricity, which often means greenhouse gas emissions. Though the gas is clear, hydrogen is described with a rainbow of colors depending on its source and sustainability. Hydrogen obtained from water with renewable energy is often referred to as “green hydrogen,” and hydrogen obtained thanks to nuclear energy is known as “pink hydrogen.”

“Illinois has a larger percentage of its electricity from nuclear than any other state,” Walsh said. “We also expect to be using solar and wind power” to produce pure hydrogen, with renewables increasingly being installed in Illinois, mandated by 2021 legislation to totally decarbonize the electricity sector.

“What distinguishes this hub is all the power producers in it are carbon-free power producers,” said Horek, noting that other hub proposals would produce hydrogen powered by fossil fuels. “For every sector that’s decarbonizing, there’s probably some technology folks may think about” that could utilize hydrogen. “The point of the hub is to continue those conversations and build that uptake.”

Bioenergy company Marquis sees hydrogen as essential to decarbonizing aviation and shipping. The element is crucial for creating sustainable aviation biofuel from corn, woody waste or other biomass, explained Jennifer Aurandt-Pilgrim, Marquis’ director of innovation and market development.

“We take the hydrogen and ethanol and run it over a catalyst, that connects the hydrogen with the ethanol to make a long-chain hydrocarbon,” said Aurandt-Pilgrim. “We’re turning biofuels into alkanes — jet fuel. That is really driven by using that hydrogen to make those long-chain hydrocarbons.”

The company also plans to create “renewable” biodiesel at a sprawling new industrial site from which the fuel can be shipped around the world via railroads or the Illinois River, which leads to the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico. A Department of Energy-funded hydrogen hub could help production scale and lower costs.

Marquis’ corn ethanol plant produces about 400 million gallons of ethanol per year, 1 million tons of high-protein animal feed, and about 1.2 million tons of biogenic carbon dioxide emissions. But some of that carbon dioxide, along with other carbon oxides near the Marquis industrial site, could be turned into more ethanol in a “fermentation” process pioneered in part by Argonne. Marquis is planning to partner with LanzaTech, another member of the MachH2 coalition, to use this process at their site.

“You increase the same kernel of corn’s yield by 50% with no more land use, because we’re bringing hydrogen in,” said LanzaTech vice president of government programs John Holladay.

Aurandt-Pilgrim said it will take time to scale the carbon dioxide-to-ethanol process up. In the meantime, Marquis is planning to sequester carbon dioxide from its ethanol production under the site of the 3,500-acre Marquis Industrial Complex. It also plans to sequester carbon dioxide at its facility in Wisconsin.

The Mt. Simon sandstone formation in Illinois is considered ideal for carbon sequestration, but the concept has had a rocky history in the state. Ambitious carbon sequestration plans at the Prairie State and FutureGen coal plants never materialized, and an ongoing proposal by the company Navigator to build a carbon dioxide pipeline and sequestration site in Illinois faces massive community opposition.

Aurandt-Pilgrim said that Marquis is in the process of obtaining needed permits from the EPA for sequestration, and since it is not piping the carbon dioxide offsite, the company doesn’t expect local opposition. The ability to sequester carbon is not essential to the sustainable aviation fuels plant and other hydrogen hub-related projects moving forward, she said.

Meanwhile, Holladay sees another way hydrogen can cut carbon emissions in local and global industries. LanzaTech makes technology to capture industrial carbon emissions — carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide — which makes the carbon available for everyday manufacturing uses.

“In other words, carbon dioxide is being transformed into essential materials made today from petroleum and natural gas,” Holladay said. “Hydrogen allows us to capture even more industrial carbon emissions, which will help our local industries be better stewards and more competitive in global markets. For example, our partners are making dresses, running shoes, bottles, and cleaning products that started as carbon emissions from steel production.”

Hydrogen-powered vehicles are not the central purpose of the federally funded hubs, but the production and distribution of pure hydrogen would enable fueling stations for vehicles, backers said.

A hydrogen fuel cell can power cars, trucks or other vehicles by basically separating the negatively charged electrons and positively charged protons in hydrogen to create an electrical current, with the only emissions being water vapor. The fuel cell essentially powers an electric vehicle that never needs to be plugged in, as long as the hydrogen fuel tank can be replenished.

That can be a big “if” given that little hydrogen fueling infrastructure exists today, and it’s hard to grasp an advantage over electric cars or buses, with the recent proliferation of electric charging stations. Total sales of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles number in the low thousands, almost half worldwide being in California, as of a 2017 study.

In 2016, Michigan Public Radio explored then-Energy Secretary Steven Chu’s statement that “four miracles” would be needed to make hydrogen fuel cell cars viable: cheaper fuel cells, cleanly produced hydrogen, lighter hydrogen storage tanks on vehicles, and, crucially, a hydrogen distribution network. “If you need four miracles, that’s unlikely. Saints only need three miracles,” Chu told MIT Technology Review.

Jamie Fox, a Chile-based principal analyst at Interact Analysis which has focused on the sector, said he doubts hydrogen fuel cell cars will ever catch on. “It’s too expensive, and it’s too late to catch up with battery electric,” he said.

But heavy vehicles that have trouble holding enough electricity in a battery could be prime candidates. A major goal of the proposed hub is helping to power industries and transport modes that are “not easily electrified,” as Walsh said, including aviation and heavy manufacturing.

Fox noted that early-stage hydrogen-fueled trains already exist in Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom, and they “might make sense somewhere where you can’t have an overhead line [for electricity] due to the terrain.” He noted that battery performance suffers in cold temperatures, perhaps opening another opportunity for hydrogen fuel cells that fare better comparatively.

Meanwhile, hydrogen can also be burned in an internal combustion engine similar to a gasoline or diesel engine, and conventional internal combustion engines can be converted to burn hydrogen. This reaction produces no carbon dioxide or public health-harming particulate matter, though it can produce nitrogen oxide. Hydrogen internal combustion engines have not been deployed widely, though some sports cars have used the technology and engine manufacturers like Cummins are increasingly considering it as a way to cut carbon emissions.

Interact Analysis reported that its research “shows that mass production of hydrogen ICE [internal combustion engine] vehicles is set to take off within the next 5 years. Currently, the TCO [total cost of ownership] is unfavorable compared to traditional ICE vehicles, but shipments will reach 58,000 by 2030” internationally.

Jim Nebergall, general manager of hydrogen engine business at Cummins, wrote that hydrogen internal combustion engines could be ideal for long-haul trucking and “harsh conditions,” while hydrogen fuel cells make more sense for lighter vehicles. He acknowledged that it’s “a running joke in the industry that hydrogen cars are always 10 years away,” but he wrote that interest in hydrogen internal combustion engines could drive the availability of hydrogen, boosting fuel cells’ prospects:

“As these commercial applications become mainstream, hydrogen fueling networks will appear to serve them. Conceivably, these limited networks could then be used by personal hydrogen cars. Hydrogen engines are just around the corner, so hydrogen cars may have a shot at revival within less than ten years after all.”

Meanwhile hydrogen gas stored under high pressure is explosive, a liability that may make its use less popular, especially for vehicles. But proponents are unfazed.

“There are safety issues with every energy source,” Walsh said, citing lithium-ion batteries that can catch on fire. “These can be handled correctly.”

Scientists and engineers can likely find new ways to pursue Chu’s “four miracles” and make hydrogen production more sustainable and less costly, and more available for everyday people. For example, Chinese researchers in 2021 announced that nanoporous cubic silicon carbide could be used to harness sunlight directly to make hydrogen gas from water.

Researchers at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory with partners recently announced their process to make pure hydrogen from methane without carbon dioxide emissions, using a catalyst to produce solid pure carbon and “blue hydrogen,” or hydrogen from natural gas with zero carbon emissions. Marquis is also planning to explore blue hydrogen production in the future, Aurandt-Pilgrim said.

“A lot of energy sources have had to go through a phase where there was an initial investment before that energy source became reasonable to use,” Walsh said. “We’ve had many decades of effort on producing batteries — lithium-ion battery work has been going on for literally decades. There is an imperative here; the imperative is we really need to have cleaner sources of energy.”

Meanwhile, he said the technology already exists to create a hydrogen-based energy economy in the Midwest, and MachH2’s hub would focus on tapping such existing knowledge and scaling up for economic benefit in the nearer term.

“This hub is not for fundamental research — the university research is in moving the technologies forward and then evaluating the technologies as they get deployed, making sure we have what we need,” Walsh said. “There is a transformation that’s going to be happening here. It’s probably less impactful immediately to most people in society because of the sectors we’re working in at first. But this will be happening and there will be job opportunities.”

PORTSMOUTH — Siemens Gamesa announced Monday that it plans to build the United States’ first offshore wind turbine blade facility at the Portsmouth Marine Terminal, notching a major win for Virginia as it strives to become a hub for the nation’s fledgling offshore wind energy industry.

The announcement was made Monday at the terminal by U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm and Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam.

The Spanish-German wind engineering company said it plans to invest more than $200 million in the Portsmouth Marine Terminal facility, which will produce blades for offshore wind projects throughout North America, per Northam’s office.

The facility is expected to create over 300 jobs.

Virginia’s largest electric utility, Dominion Energy, previously selected Siemens Gamesa as the turbine supplier for its 2.6 gigawatt Virginia Coastal Offshore Wind project being developed 27 miles off the coast of Virginia Beach. A 12 megawatt pilot constructed by Dominion became the nation’s first offshore wind installation in federal waters and began delivering energy to customers in January 2021.

Offshore wind is increasingly becoming a critical component of both electric power producers’ plans to transition away from fossil fuels and state and federal aspirations to develop renewable energy that can replace coal and natural gas while driving economic growth.

Earlier this month, President Joseph Biden’s administration laid out an ambitious plan to develop offshore wind along much of the East Coast, West Coast and Gulf of Mexico. In March, the administration set a target of deploying 30 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030.

Virginia has also set an aggressive goal under the 2020 Virginia Clean Economy Act of developing 5.2 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2034. Dominion’s CVOW project, which would produce half of that power, is currently being reviewed by the U.S. Bureau of Ocean and Energy Management.

But even as states race to develop wind projects, turbine components continue to be produced overseas, with major manufacturers including Siemens Gamesa telling Reuters earlier this year that they need to see a reliable pipeline of projects moving forward in the U.S. before putting down roots stateside.

Shipping turbine components across the Atlantic for U.S. projects, however, comes with special challenges.

Under the federal Jones Act, any vessel carrying goods between two points in the U.S. must be built and registered in the United States. Despite that restriction, no such vessels with the capacity to transport turbine components currently exist in the U.S. Dominion is building the first Jones Act-compliant offshore wind installation ship in Texas, which has been christened Charybdis after a sea monster in “The Odyssey” and is expected to be completed by late 2023.

Virginia Mercury is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Virginia Mercury maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Robert Zullo for questions: info@virginiamercury.com. Follow Virginia Mercury on Facebook and Twitter.

New Hampshire’s electric utilities have come out in favor of continuing the state’s current system for compensating customers who share surplus solar power on the grid.

Eversource, Unitil, and Liberty Utilities surprised clean energy advocates by submitting joint testimony to state regulators last month endorsing the state’s current net metering structure. The program credits customers roughly 75% of the standard electricity rate for any unused solar generation that flows back onto the grid and is used by other customers.

“I am delighted that our utility friends have come over to our way of seeing things,” said Sam Evans-Brown, executive director of Clean Energy New Hampshire.

The utilities’ testimony is part of New Hampshire’s current deliberations over whether the state’s net metering rules should be adjusted. The process in New Hampshire is playing out as many other states are also debating what role net metering should play in the transition to clean energy.

Net metering provides an important source of revenue for solar customers when their generation doesn’t perfectly match their electricity use, but critics contend that it unfairly shifts costs to consumers who don’t generate their own renewable energy.

“I think renewable energy is great,” said Rep. Michael Vose, chair of the state House’s Science, Technology and Energy Committee, who has supported bills that would have cut net metering rates. “If people can afford to buy it and want to buy it, they should go ahead, but I am not in favor of subsidizing renewable energy and shifting costs to people who don’t directly benefit from that renewable energy.”

New Hampshire’s current rules, put in place in response to 2016 legislation, replaced a previous system that gave participants credits equal to the price utilities charge customers for electricity. This same law also required the state to conduct studies on the impact and effectiveness of net metering and make changes to the regulations if the findings warranted.

Previously, the utilities had advocated for much lower rates for net metering customers. Nationally, utilities have often taken the same position as well, arguing that higher net metering rates push costs onto customers who can’t afford to buy solar panels.

At a glance, it’s easy to dismiss: if a homeowner sends 1 kilowatt-hour of power to the grid and receives a credit worth the price of 1 kilowatt-hour, it would seem everything should come out even. But the retail price of electricity includes more than just the cost of the power itself — everything from the salaries for lineworkers who do maintenance to the cost of debt on construction projects to keep the wires and poles safe and reliable.

“The whole system is packaged up and rolled into the price,” Evans-Brown said.

So when a homeowner receives a full retail credit for their power, they are getting paid for more than just the energy they are providing, increasing the cost to run the utility. These costs are then passed on to the utility’s entire consumer base. A lower net metering credit means less of this sort of cost shifting and, some argue, a fairer deal for customers without solar.

The gap between net metering rates and utility costs can be even more pronounced at certain times of day. In the early afternoon on a sunny summer day, demand on the grid is low, meaning the price for power from the grid drops as well. At the same time, solar panels are producing plenty of excess energy. Utilities can end up paying higher rates for this electricity than they would have had they been buying from a power plant, at a time when excess residential solar energy wasn’t even needed to help meet high demand.

“Solar does not make the grid more reliable or resilient, nor does it improve power quality in any way,” Thomas Meissner, chief operating officer of Unitil, testified in 2016.

Supporters of a strong net metering rate, however, argue that net metering creates an array of benefits for utilities that solar generators should be compensated for. The report produced in accordance with the 2016 law notes that solar can reduce capacity payments the utilities must make, reduce the cost of complying with renewable energy standards, and lower the amount of power lost traveling through transmission lines, among other benefits.

Utilities, however, have generally downplayed these benefits. However, in their joint testimony, the utilities go so far as to praise the economics of the system.

“New Hampshire’s net metering policy — which is among the most balanced in New England — has been effective in encouraging the growth of [solar] resources in our state, and there is no evidence that the current compensation level is creating unjust cost shifts,” said Eversource spokesperson William Hinkle, after the testimony was filed.

The state report presents similar findings. It concludes that distributed solar generation should provide increasing value to the grid over the next 12 years. It also found evidence that limited cost shifting would occur, increasing the average residential bill in the range of 1% to 1.5%.

Supporters of net metering say this number is so small that it is an acceptable price to pay for the benefits of increased renewable energy. Vose, however, is concerned about any increased costs for consumers who have not chosen to install solar panels.

“That is one of the problems we’ve tried to ameliorate, to minimize such cost shifting whenever possible,” he said.

Nationally, net metering remains contentious in many states. For example, North Carolina’s public utility authorities have angered environmental groups and many in the solar industry by approving a utility plan to reduce payments to net metering customers. And earlier this year, California cut rates by about 75% for new net metering customers, with utilities pushing for even more cost-cutting concessions.

“They’re hugely disincentivizing rooftop and community solar,” said Patrick Murphy, senior scientist at PSE Healthy Energy, who researches clean energy transitions and energy equity.

Overall, the more a state lowers its net metering credits below the retail price, the more likely utilities are to embrace — or at least accept — the program, Murphy said. In New Hampshire, the reduction from full retail price to 75% has been enough to satisfy utilities.

The New Hampshire net metering docket remains open and the matter is under consideration by the Public Utilities Commission. Vose thinks it very possible that net metering rates will be further lowered. Evans-Brown, however, thinks the utilities’ recent testimony could have a significant influence toward keeping the current system in place.

“This makes it more likely that we will get a favorable outcome,” he said.

👋 Hello and welcome to Energy News Weekly!

The Biden administration is about to get more young Americans working for the planet.

Last week, the White House announced it’s launching an American Climate Corps. The workforce training and service program aims to get young people ready for climate and clean energy fields. It will put an initial cohort of 20,000 to work installing clean energy technologies, restoring coastal wetlands to prevent flooding, and taking on other jobs in climate-vulnerable communities.

It’s all reminiscent of the New Deal-era Civilian Conservation Corps, which hired young people to fight forest fires, build wildlife refuges, and take on other environmental jobs during the Great Depression.

Flash forward to the 21st century, and a Climate Corps has been a priority for Democratic lawmakers. The Biden administration initially proposed the work program as part of its Build Back Better infrastructure plan, but it was left out of the Inflation Reduction Act. But by combining programs and funding authorized in the climate law and other legislation, the White House has created something pretty close to the program it’s been working toward for years, Inside Climate News reports.

There are a lot of details we don’t yet know about the American Climate Corps, including how interested workers can apply and how much they’d be paid. But for now, there’s a White House website where you can share if you’re interested in joining or otherwise helping the burgeoning corps out.