Massachusetts officials are proposing policy solutions to address a bureaucratic backlog that municipal leaders and clean energy advocates say is bogging down one of the state’s most successful drivers of clean electricity purchases.

Nineteen communities across the state are waiting for public utility regulators to rule on proposed community choice aggregation plans, in which local governments negotiate with power suppliers for lower prices or a higher share of renewables.

Some of these municipalities have been waiting for more than two years to launch their programs. Another 16 are waiting to see if the state will let them modify existing programs. As the proposals languish, municipalities are missing out on chances to save residents money and cut carbon emissions.

In response to this backlog, the state energy department has proposed a new system to streamline the process, though many advocates are highly skeptical of these guidelines.

“I’m not sure that the way they’ve drafted them is really going to address the backlog,” said Martha Grover, sustainability manager for the city of Melrose, which first adopted community choice aggregation in 2015 and has held off updating the program in recent years because of the delays.

In addition, state Rep. Tommy Vitolo has introduced a bill that would require faster response times and allow municipalities to make some changes to programs without seeking state approval.

Massachusetts was the first state to introduce these programs, as a part of electricity restructuring legislation passed in 1997. The policy allows individual cities and towns or groups of municipalities to use the promise of a built-in customer base to negotiate with power suppliers for prices. Generally, residents are automatically enrolled but can opt out at any time.

The Cape Light Compact, a group of 21 towns on Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard, formed the state’s first aggregation program in 2000. The idea was slow to catch on, however, until electricity prices started rising in 2013 and 2014, prompting more municipalities to seek alternatives. Today, there are 168 municipal aggregation plans active in the state, saving consumers more than $200 million annually, according to a report from the nonprofit Green Energy Consumers Alliance.

Though not explicitly an emissions reduction program, aggregation also allows municipalities to include more renewable energy in their portfolios than legally required. And many of them do exactly that: 76 of Massachusetts’ aggregation programs included extra renewable content in 2022, according to the consumers alliance. Another 40 communities let individual residents opt-in to higher levels of renewable energy. In 2022, Massachusetts’ green energy aggregation programs increased demand for renewable energy in the state by more than 1 million megawatt-hours, the Green Energy Consumers Alliance calculated.

“There is no other program in the commonwealth that produces cleaner electrons without subsidy,” said alliance executive director Larry Chretien.

The delays were first caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a statement from the state energy department. Additionally, the complexity of the rules and requirements for a successful application have also slowed things down, state officials and municipal leaders agree. Each time regulators rule on a plan, any new precedent set by that ruling must be complied with by all future applicants. This requirement makes it hard for municipalities to understand the rules and forces frequent revisions. It also makes it more painstaking for the state to ensure a proposal meets the ever-changing slate of requirements.

“There are now 168 approved plans and we are held accountable to rules and ways of operating that are buried in the footnotes,” Grover said.

The state has responded to the backlog by releasing draft guidelines that summarize and simplify the detailed requirements. It has also issued an application template and proposed an expedited approval process for municipalities that use the template.

“Addressing these delays is a top priority for the [Department of Public Utilities], and we look forward to announcing finalized guidelines that will help facilitate a timely review of applications,” said department chair Jamie Van Nostrand.

For many municipalities, however, the guidelines make no changes to the process, but only formalize the existing approach, which many say amounts to micromanagement. At least eight cities and towns have filed testimony so far arguing that the proposal erodes local control and would be unlikely to speed up approvals. The draft guidelines would make the process “more burdensome and less efficient,” testified Michael Ossing, city council president in Marlborough, which adopted community choice aggregation in 2006, saving residents an estimated $26 million over the past 17 years.

“Aggregation should be under municipal control,” said Anthony Rinaldi, an Amesbury city councilor. “We should control how we implement the program, how we inform our citizens. But they want to control every little thing.”

Vitolo’s bill offers an alternative approach. It would address the delays by requiring the state to issue a decision on aggregation applications within 90 days. If this deadline is not met, a program would automatically be approved. If regulators rejected a program, and applicants resubmitted an amended plan within 30 days, the state would then have 30 days to issue a decision.

The bill would also allow cities and towns to make certain changes — including periodic changes to prices and product offerings, means of providing notifications to customers, and sharing translated materials — to their programs without returning to utility regulators for approval. Vitolo points to Boston, which launched a community choice program in 2021, as an example: the city wants to distribute translations of its information materials, but can’t do so without getting in the slow-moving line for approval.

“It’s been frustrating,” Vitolo said. “We want to allow these aggregators to make simple straightforward changes without going to the [state].”

Vitolo’s bill had a committee hearing in late September. Now supporters must wait to see if it gains traction in the legislature.

Shuttered during the pandemic, the historic Strand Theatre in Pontiac, Michigan, faced an uncertain future. But previous energy efficiency investments provided a lifeline.

The Strand was able to use C-PACE — commercial property-assessed clean energy financing — to retroactively fund and refinance those investments, essentially rolling the cost into their property taxes to be paid over time and freeing up cash for them to wait out the pandemic.

While the pandemic and worker and supply chain shortages have made the last two years rough across countless sectors, Michigan’s C-PACE program nonetheless enjoyed its best two years ever in 2020 and 2021, with 28 projects closed including the Strand.

This year at least five local jurisdictions in Michigan saw their first-ever C-PACE project, and four more are expected to do so this year or in early 2022. That’s according to Todd Williams, president and general counsel for Lean & Green Michigan, the company that administers C-PACE in the state, and recent winner of the Michigan Energy Innovation Business Council’s Business of the Year Award.

“PACE was a form of rescue capital for [the Strand]. It allowed them to refinance some loans, delay some payments, maintain the business through hopefully the end of the pandemic,” Williams said. “It was like a second mortgage on your house. You’ve already completed the projects, they’ve already been funded, and this is a method in which they were able to draw some capital back out. It was not necessarily a large project, but without it, it’s completely possible an asset in that community would have closed.”

As the Strand’s experience shows, C-PACE can be a tool not only to install solar or make energy efficiency improvements, but to provide financing in general, since it can free up capital immediately that businesses might otherwise have used on investments that qualify as clean energy or resiliency-related. This potential may be even more attractive in uncertain and rocky economic times like the current moment.

“Commercial PACE can be your financing tool to fill a financing gap and meet energy efficiency goals at the same time,” said Cliff Kellogg, executive director of the C-PACE Alliance, at a panel during the Urban Land Institute’s annual conference in Chicago in October.

Mansoor Ghori, co-founder and CEO of Petros PACE Finance, said during the panel that since many businesses didn’t know how long the economic uncertainty and recession caused by the pandemic would last, they “refinanced their equity using PACE, and used that money to make sure they had enough capital to get through however long it would take.”

“Covid for the PACE industry was actually an accelerant,” Ghori continued. “When other sources of capital seized up or pulled back, [businesses] had to find other ways to get projects done. All of a sudden PACE became much clearer in their eyes, they figured out what it does, how they can use it. We grew our business 300% during Covid.”

C-PACE is especially well-suited for businesses hard-hit by the pandemic, like hotels and entertainment venues, and indeed hospitality is the sector that has most utilized C-PACE funding thus far, followed by office and retail, according to the trade organization PACE Nation.

During the Chicago panel, Kunal Mody, CEO of Blueprint Hospitality — which works on PACE financing with hotels — noted that during the pandemic the tool “helped us move our trapped equity back out and refinance.”

Ryan Hoff, project manager at the engineering firm Bernhard, during the panel pointed to a number of hospitality projects his company has worked with nationwide, including a 60,000-square-foot hotel in Wisconsin that tapped $4 million in C-PACE financing. A Marriott hotel in Columbus, Ohio, in 2018 worked with Petros to retroactively tap $16.3 million C-PACE funding, a project that was the second-highest value C-PACE project in the country that year.

Williams noted that Treetops Resorts, “a classic golf and ski resort,” became northern Michigan’s first C-PACE project, with a retrofit that had been in the works for several years. The resort leveraged $2.9 million in C-PACE funding for a comprehensive energy efficiency overhaul projected to greatly reduce its carbon footprint and improve visitors’ experience. A Michigan Comfort Inn & Suites also tapped C-PACE for improvements last year.

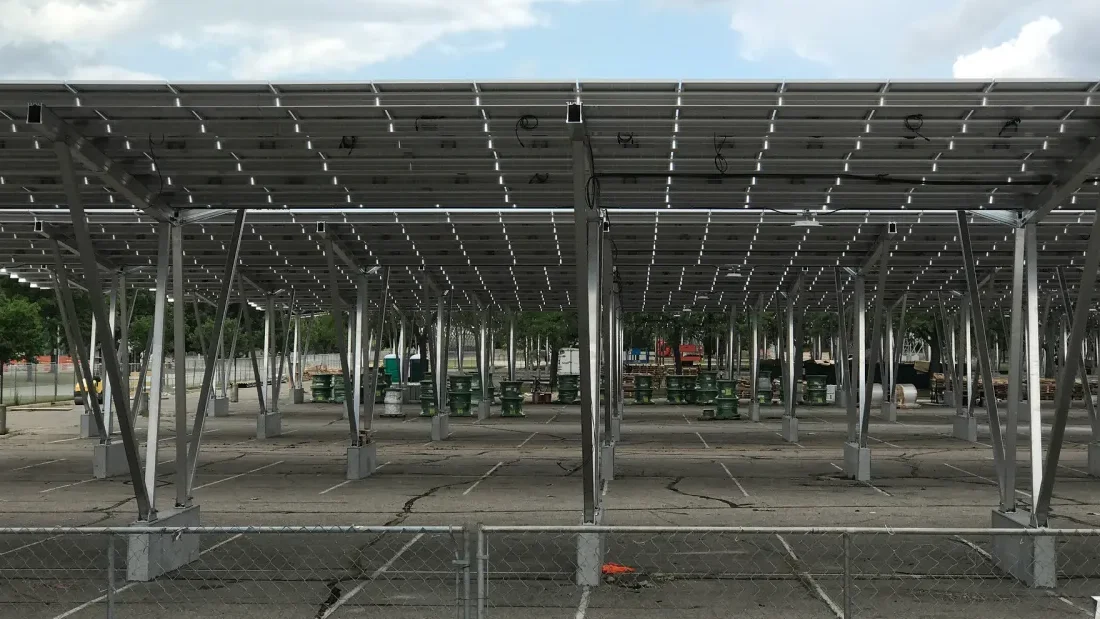

Michigan also saw C-PACE used for new construction, including for The Henry, luxury townhomes near Ann Arbor that leveraged nearly $2 million in PACE financing for solar panels, LED lighting and other energy efficiency measures, in line with marketing the complex to environmentally aware young professionals. In September, construction started on a residential and commercial project in Detroit’s Greektown that, at $13 million in C-PACE financing, is the largest C-PACE project in the state. A fifth of the project’s rental units will be affordable housing, and it is seen as key in revitalizing that part of the city.

Williams said senior living facilities are especially well-suited to C-PACE funding, and Michigan has closed four such deals this year with another in the works.

“That’s become a trend nationwide where senior living projects are taking advantage of PACE,” he said. “They tend to be extremely long-term facilities; it fits well with the design of the property and how the property will be used.”

In all, Michigan has seen C-PACE support 52 projects totaling $115 million since 2015, with 17 projects this year alone. The investments included at least 13 solar installations, three EV charging stations and two green roofs, plus numerous energy efficiency and energy storage overhauls. Williams said he still sees C-PACE as in the early stages, but quickly growing.

“It’s just starting to self-perpetuate a little more. We’re not having to wave the flag quite as heavily — a lot more flags are being waved,” he said.

At least 38 states have laws allowing commercial PACE financing. Once a state passes such enabling legislation, then local jurisdictions need to pass their own ordinances to actually carry out the program. In the Midwest, Ohio, Michigan and Minnesota have robust programs, Illinois has a nascent program and Indiana, Iowa and Kansas do not currently have C-PACE enabling legislation, though efforts are underway in Indiana, according to the C-PACE Alliance.

Wisconsin’s growing C-PACE program saw at least one major project during the pandemic, as developers of the former Oscar Mayer headquarters in Madison, Wisconsin, used $7 million in C-PACE refinancing to overhaul windows, lighting and other efficiency measures in the mixed-use OM Station, which now leases to industrial, office and “creative” tenants.

Chicago, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh are among cities that have launched their programs in recent years. The need for local legislation means the process of actually rolling out C-PACE projects is slow, but advocates hope it gains prominence and becomes more of a priority for local leaders especially given the particular potential it offers in the current economy.

“C-PACE financing involves no public dollars whatsoever,” Ghori said. “The role of the state and local government is simply to approve the availability of this kind of financing.”

The trade organization PACE Nation says on its website that in all more than $2 billion has been invested in 2,560 commercial projects nationwide, with energy efficiency making up 49% of the investment and renewable energy representing 23%. Cumulative investment has grown from just over $100 million in 2014. California led the cumulative investment tally with $625 million, followed by Ohio at $376 million. Minnesota and Michigan ranked sixth and seventh, and Wisconsin ranked 11th, though current investment totals are likely higher.

Illinois passed legislation enabling PACE in 2017 and updated it in 2019 to include resiliency as among the categories eligible for financing. In 2019, before the pandemic set in, Eric Alini, CEO of Counterpointe Energy administering C-PACE in Chicago, predicted that “2020 will be the year of PACE in Chicago.” In May 2020, a hog slaughterhouse owned by the company JBS in Illinois launched its 2.6-megawatt solar installation made possible by C-PACE financing.

Alini said that about a dozen capital providers have signed on to provide financing for Chicago C-PACE projects, environmental groups have been helping to raise awareness, and the queue for potential projects is growing.

“Commercial PACE is a strong financing option in any market because of its ability to fill a gap in a development’s capital stack or help transform a capital expense into an operating expense,” Alini said. “ In this market though, that becomes even more true as you see mortgage lenders taking a more conservative approach to their portfolios.”

“We’re now at the tipping point,” Ghori said, “where we’ve got enough states and enough programs that are live — we’re starting to grow this market exponentially.”

The experts on the Urban Land Institute panel said they hope companies think bigger in terms of the potential for C-PACE, considering it for larger operations. Ghori pointed to his company’s $90 million C-PACE deal at the high-end office building 111 Wall Street in Lower Manhattan, calling it a “seminal moment for PACE.”

And the investments that C-PACE makes possible may be more helpful than ever given climate-related goals and the difficulty of attracting and retaining commercial tenants in the post-pandemic business landscape, with many people still working from home.

“The good news is we can have our cake and eat it too with commercial PACE financing,” Kellogg said. “Having properties that are energy efficient are desirable in attracting tenants, and also from the regulatory side, it’s a demand most of us are experiencing as a must-have. In other words, we are both getting pulled into this need for energy efficiency and we’re getting pushed into it at the same time, both as good business practice and regulatory requirement.”

Smaller, regional banks and credit unions are increasingly looking to help homeowners finance solar installations in a sign of growing recognition of the opportunities in clean energy finance.

In the Midwest, Iowa-based Decorah Bank & Trust is among the latest to begin marketing loans for solar and other clean energy projects. The community bank recently relaunched a digital subsidiary called Greenpenny to serve residential and commercial customers in Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Minnesota and Wisconsin.

It joins longtime Twin Cities clean energy lender the Center for Energy and Environment and a handful of credit unions and other community banks offering products in a space traditionally dominated by larger, national firms.

Clean energy advocates are hopeful the availability of local lenders will increase options for borrowers and provide a greater comfort level for those who might be less inclined to trust online lenders or large national banks.

Jeremy Kalin, a partner with Avisen Legal who helped the Minnesota Credit Union Network create its CU Green solar loan program, said typical residential borrowers are sensitive to “long-term value and trust” when looking for lenders. A personal connection to a bank or credit “makes a difference.”

The process often starts with referrals from solar installers. St. Paul-based All Energy Solar offers Greenpenny and Center for Energy and Environment loans to customers, as well as national lenders. “Historically, we find the national players pushing the envelope here very consistently with innovations and competing with each other to offer a diverse array of financing options that will help each customer to get the most value out of their project,” said Ryan Buege, All Energy Solar’s vice president of sales and marketing. Still, he said, if more banks developed clean energy loans, more consumers would likely become more comfortable installing systems.

Jessica Reis, vice president of communications and marketing for Greenpenny, said the bank creates a transparent loan process with no hidden fees or upfront charges, a contrast with some national lenders who use such fees to lower interest rates. The bank calls every customer who applies and communication continues via phone or email.

Greenpenny relaunched last year after struggling with an earlier rollout during the pandemic. Now the Iowa credit union has been adding staff to manage a growing portfolio. Decorah Bank & Trust CEO and President Ben Grimstad said his father, Larry, had started lending to organizations doing renewable energy projects decades ago because of his environmental interest.

Decorah, home to Luther College, has a strong ecological ethos that allowed the bank to gain experience financing more than 100 local projects, most of them solar. Grimstad wanted to expand the bank beyond Decorah and decided to create a digital offering to leverage the bank’s experience with clean energy.

“We are about a year and a half into it and it’s gone pretty well,” he said.

Greenpenny provides solar loans and a green mortgage product for efficiency, geothermal, battery storage and other carbon-reducing projects. The digital bank serves residential customers as well as small- to medium-sized commercial and industrial projects, but not utility-scale wind or solar farms.

The loans are secured by the value of the equipment, from panels to storage devices. Greenpenny President Jason MacDuff said the bank tries to set up loans that match the amount clients save monthly on their utility bills from a new solar or HVAC system. The loans require no money down.

“These borrowers, by definition, are all homeowners that tend to skew pretty sophisticated and because they’re making a pretty big investment in their home, they tend to have the means to be able to do that,” MacDuff said.

A unique short-term solar loan Greenpenny offers matches the tax credit a customer receives. The customer pays a small interest payment and then pays off the loan when the federal government disperses the 26% tax credit. A second loan covers the remaining 74% of the project’s cost.

The average residential loan size is $40,000, with commercial projects from hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars. He noted that the bank may soon finance as many as seven community solar projects in Minnesota. But plenty of deals fall through because of low reimbursements for energy by utilities or other issues.

When he joined the company in 2021, he was surprised to find so few banks offering clean energy loans. “For us to accomplish the renewable energy transition this country needs, we need more banks to be in the game helping finance these projects,” MacDuff said.

In Minnesota, the largest local option remains the Center for Energy and Environment, which has established partnerships with several cities and neighborhoods and last year financed $22.7 million in projects. Of those, 145 loans totaling $3.5 million were for residential solar, up from 89 loans in 2019. Lending services director Jim Hasnik said the organization had been lending for years for efficiency improvements before it developed a solar loan in 2014.

The loans vary in term and loan-to-value size, with interest rates increasing as the length of loans climbs. Project sizes have grown, and business has been brisk this year as the popularity of solar has grown. The center requires installers to have a builder’s contractor license following a recent string of solar company bankruptcies in the state.

Solar loans remain a niche product. The Minnesota Credit Union Network’s CU Green program launched with two credit unions — Affinity Plus Federal Credit Union and Hiway Credit Union — and has seen no others join the effort. Mara Humphrey, chief advocacy and engagement officer for the network, said some credit unions have begun discussing whether to add solar loans to their portfolios, but she believes many still lack understanding of clean energy projects and will have to see demand grow before creating products for customers.

Affinity Plus had a rocky start before dropping a requirement that homeowners first hire someone to conduct a home appraisal. Members can now apply digitally for loans and receive the money the same day.

Chief Retail Officer Corey Rupp said the new solar loan program did more volume in six months than the home equity-based one did in four years.

“I think homeowners are a little more comfortable with it,” Rupp said. The credit union is now studying loans for electric vehicles, commercial efficiency, and solar projects.

Correction: The $22.7 million CEE lent was for about 1,200 loans.

Wisconsin solar advocates want regulators to look to Iowa’s example as they consider the latest skirmish over how solar projects are financed in the state.

The Wisconsin Public Service Commission is considering two petitions seeking authorization for third-party-owned solar projects, in which the entity that owns the array is different from the property owner that will use the electricity.

The financing mechanism makes solar viable for many cities, schools, and nonprofits, as well as residential customers who can’t afford the upfront cost of a solar array. It’s also been the subject of a long legal and regulatory battle between solar advocates and Wisconsin utilities that see it as a threat.

That was once true in Iowa, too, until 2014 when the Iowa Supreme Court affirmed that a third party can own a solar array and sell the power, or make lease payments, to the owner of the property without becoming a public utility. In the eight years since then, experts and advocates say utilities’ fears over such ownership opening the door for “deregulation” or other negative impacts have not materialized.

“Iowa is still very much a utility-dominated state with a vertically integrated utility structure, and with less than 2% of generation from distributed resources,” said Karl Rábago, an energy consultant based at Pace University School of Law, testifying on behalf of the advocacy group Vote Solar in one of the pending cases. “Moreover, since the 2014 court decision, I am not aware of movement in the state toward deregulation or retail choice.”

(Rábago also provides occasional editorial feedback to the Energy News Network as a member of a reader advisory committee. See our code of ethics for more information.)

Iowa’s court decision resulted from Dubuque-based developer Eagle Point’s lawsuit challenging Alliant Energy’s refusal to interconnect a third-party-owned array to the grid. Eagle Point has also been central to the standoff in Wisconsin, after utility We Energies refused to interconnect solar co-owned by Eagle Point and the city of Milwaukee.

The latest petitions related to third-party solar in Wisconsin were filed in May. Vote Solar asks that the Wisconsin Public Service Commission allow a Stevens Point family to enter a third-party ownership arrangement for an 8.6-kilowatt system. The petition notes the energy savings would help them pay for college for their two teenage children, and a third-party structure is necessary to avoid upfront costs. That family lives in territory served by Wisconsin Public Service Corporation, which like We Energies is a subsidiary of utility company WEPCO.

The Midwest Renewable Energy Association petition asks the commission for a declaratory ruling clarifying that third-party solar is legal, and notes that it would be too expensive and difficult for every customer who wants the arrangement to file their own petitions.

Public hearings for both proceedings will be held on Nov. 2, and public comments are being accepted through Nov. 9.

“There is simply no reason to believe that Wisconsin’s experience with third-party-financed distributed energy systems would track any differently than what we’ve seen in Iowa,” said Michael Vickerman, program and policy director for Renew Wisconsin. “Third-party financing will not usher in mass defections from the grid, nor will it, by itself, push energy rates higher. But it would certainly broaden the customer base that Wisconsin solar contractors would serve, including low- to moderate-income households who will have less success accessing federal tax credits than their more affluent counterparts.”

A 2021 report by Iowa’s state auditor showed that a total of 80 public entities had installed solar, mostly since the 2014 court decision, saving an average of over $26,000 a year on energy as a result. The report noted that schools have hired an extra teacher, avoided closing and otherwise benefited from the savings.

Since the Iowa ruling, Eagle Point has developed dozens of third-party-owned installations for Iowa schools and municipalities, including recent arrays installed on the fire station and water treatment plant in the city of Hills, Iowa, and a 300-kilowatt array for Upper Iowa University. Eagle Point CEO Jim Pullen said the company has signed about 20 contracts with municipalities just this fall.

“It’s not that complicated,” Pullen said. “By and large I don’t believe the utilities have made any statements about [third-party ownership having] deregulated the market or destabilized the market. They treat a third-party project exactly the same as a customer-owned project. There’s no difference from our perspective when we’re interconnecting, and they don’t seem to care anymore.”

The utilities that had opposed third-party ownership in Iowa — Alliant Energy and MidAmerican Energy — did not respond to questions about their past opposition to third-party financing or its current impact. Spokespeople for both utilities said the companies support renewable energy and offer options for customers to access renewables, including an Alliant program wherein the utility pays customers to place utility-owned solar on their rooftops.

“Alliant Energy focuses on making renewable energy accessible for everyone — in order to keep it affordable for everyone,” says a statement provided by Alliant. “We support energy policies that ensure a fair, affordable and reliable energy network for all customers and communities. … We support our customers’ interests in solar through a variety of mechanisms, including utility-scale solar, community-based solar and interconnection of customer-owned systems.”

The Iowa state auditor’s report notes that Iowa has 99 counties and 330 school districts. “If each county, each county seat, and each school district created a solar installation of the average size of these installations [already developed with third-party ownership], over the installations’ lifetimes Iowa taxpayers could expect to net over $375 million in savings,” the report says.

The Iowa state auditor also surveyed schools and cities about public reaction, and found significant public support. The Bennett Community School District, for example, credited its $53,000 energy savings for helping to keep the school open to its 88 enrolled students. The city of Cedar Rapids received feedback that its panels — developed with Eagle Point — were unattractive, and planted trees to improve the view.

“At a high level, third-party ownership is doing exactly what we thought it would do” in Iowa, said Josh Mandelbaum, a senior attorney with the Environmental Law & Policy Center: “Providing greater choice and flexibility for individuals and organizations that want to pursue solar.”

We Energies and other utilities have argued that third-party ownership undermines the utility’s ability to keep up the grid and serve its customers, since the third-party owner is essentially competing with the utility and the customer is paying less to the utility. The Wisconsin Utilities Association offered expert testimony during the petition proceedings — including from a former California utility commissioner — regarding the negative impacts of net metering and solar proliferation.

But Environmental Law & Policy Center senior attorney Brad Klein argued that this “cost-shifting” argument, often made by utilities nationwide, is separate from the legal question of whether a third-party owner is functioning as a utility.

“Some of the arguments you see are not specific to the legal question regarding whether providing financing options creates a public utility; they are more broadside attacks on distributed energy resources generally,” Klein said. “We saw that in Iowa — a mischaracterization of the impact of third-party financing.”

Meanwhile, the idea that distributed solar unfairly shifts costs to customers without solar and jeopardizes grid reliability has been widely challenged with evidence showing more distributed solar generally makes the grid more efficient and resilient, benefiting all customers.

“The impact of third-party financed solar on Iowa’s electric rates? Negligible,” said Renew Wisconsin’s Vickerman. “If anything, the gap between Iowa’s and Wisconsin’s electric rates has widened since 2014.”

The Environmental Law & Policy Center cites a 1911 Wisconsin Supreme Court case, Cawker v. Meyer, wherein the court ruled that a company selling heat and power to several neighbors did not constitute a public utility because of its limited scope. Case law says utilities’ rights to operate as regulated monopolies must be protected for the interest of customers, not the utilities’ competitive interests, furthering the argument for third-party solar as advocates see it.

Once third-party financing becomes commonplace, the success and popularity of such arrays depend in part on net metering policies that typically apply equally to directly owned and third-party-owned projects.

In Iowa, advocates say utilities have done nothing since the Supreme Court decision to impede third-party-owned arrays specifically, but struggles over distributed solar continued. The Environmental Law & Policy Center and other advocates were upset with a 2019 utility-backed bill that would have gutted net metering for all distributed solar, including third-party-owned arrays. Ultimately 2020 state legislation established inflow-outflow billing that will transition to a value-of-solar tariff. That compromise was supported by clean energy groups, though they have clashed with utilities over its implementation.

Third-party ownership allows nonprofits like schools, government agencies, churches, hospitals and social service agencies to collect tax benefits even though they do not pay taxes, since a private developer owns and operates the solar installation, passing their tax savings on to the customer. The model also makes rooftop solar feasible for private residents or other entities that cannot afford the upfront capital, and lower-income families who do not earn enough to owe taxes that could be slashed through the credit. Third-party ownership becomes even more important since the Inflation Reduction Act extended the federal investment tax credit for solar, advocates say.

“We’re focused on getting more folks and organizations and farmers and businesses to own more of the energy that’s around their properties — whether wind, solar, geothermal,” said Jason MacDuff, president of Greenpenny, an Iowa-based, sustainability-focused bank that funds many third-party-owned solar projects. “They should be able to harness the power and be able to deploy it so they can preserve their own resources. That’s important for economic development, especially in rural areas.”

The Bad River Tribe in northern Wisconsin was able to install three solar-powered microgrids with battery storage through third-party ownership, since they are not regulated by the Public Service Commission or subject to state law as a Native American tribe that gets power from an electric cooperative. The nonprofit that partnered with the tribe on the project, Cheq Bay Renewables, argued in a public comment in the Vote Solar case that third-party ownership is a social justice and equity issue.

“Equity has risen in importance across all Federal and State decisions, and should be applied to TPF [third-party financing],” Cheq Bay Renewables president William Bailey wrote in the public comment in the Vote Solar case. “TPF is just another financing tool to allow a more rapid and equitable expansion of clean energy. … This docket is not about one family, but rather could set policy throughout the state.”

A Cleveland, Ohio, green bank is leading a multi-state effort to secure a chunk of $7 billion in funding for low-income residential solar installations under the federal Inflation Reduction Act.

Growth Opportunity Partners, a community development corporation focused on underserved, low- and moderate-income communities in Ohio, is spearheading an application by about 20 counties in seven states that are collectively seeking $250 million to help low-income residents access solar power. It operates the GO Green Energy Fund, the nation’s first Black-led green bank program.

Growth Opps CEO Michael Jeans recently spoke with the Energy News Network about how GO Green Energy fits into the nonprofit organization’s broader mission to help underserved communities.

Through consulting and capital services, Growth Opps is “providing financial solutions in communities that have been underinvested in and disadvantaged,” Jeans said. As Growth Opps worked in those communities in Ohio’s urban and rural areas, however, he and colleagues saw that people’s health and well-being were a big concern.

Conversations with health executives, foundations and others led to the concept of the GO Green Energy Fund as a way to address some of the causes of health problems at a community level, as opposed to a case-by-case basis.

“We may, at a systems level, be able to create access for those who would like to see a better life for themselves, who would like to see cleaner communities,” Jeans said.

Growth Opps was incorporated in 2015, and the GO Green Energy Fund began in 2020 — two years before Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act. Among other things, the law authorizes the Environmental Protection Agency to implement its $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, which the EPA says is meant to mobilize “financing and private capital for greenhouse gas- and air pollution-reducing projects in communities across the country.”

“Thankfully for us, there’s natural alignment,” Jeans said.

“We are the Industrial Heartland Solar Coalition,” Jeans said. “It’s a county-by-county regional focus across multiple states and an opportunity for there to be equity in the process.”

Growth Opportunity Partners is the lead applicant. The coalition’s members include roughly 20 counties and their communities in Ohio and states from Missouri, Indiana and Michigan to parts of Pennsylvania, New York and West Virginia. Group members in Ohio are Cuyahoga, Summit, Franklin, Hamilton and Montgomery counties, which include the cities of Cleveland, Akron, Columbus, Cincinnati and Dayton.

The coalition hopes to get $250 million under the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund’s $7 billion Solar for All category, which aims to tackle barriers to disadvantaged communities’ participation in distributed solar generation.

“These dollars need to be catalytic. This is a seed investment for this work,” Jeans said, meaning the funding is meant to spur additional funding from other sources, including capital markets, businesses, philanthropy and other sources. Otherwise, “we will have undercapitalized the effort this is going to take.”

Jeans said the group hopes to hear back from the EPA sometime in the winter, with a possibility for funds to start flowing in July. With disruption in Congress, however, those goalposts could move.

“There are other things that come along with that,” Jeans said, including whether rooftops are ready for solar. Also, “under the rest of our legacy work at Growth Opps, are there other things we should be considering? Should we look at appliances for upgrades? Weatherization to further save money? There are incentives and rebates that are available at the household level.”

“If we can get [distributed solar power] to the homes that have high energy burdens — meaning too much of their check is going to pay for the cost of utilities, then we can have significant impacts here,” Jeans said.

The work can provide job benefits for people in disadvantaged communities, too. “We’re in a position to add skills, increase income and increase opportunity while cleaning up the environment for our families and our neighbors,” Jeans said.

“There’s a level of trust that has to be earned,” Jeans said. “When places have been underinvested in and people have been disinvested in, then it’s difficult to believe that the next knock on the door is one that’s welcome.”

Earning that trust calls for caring and listening to people about their needs and lived experiences, Jeans said. “We know these people. We know many of the occupants in these communities. We have a diverse team, and we’ve grown up in many of these communities.”

“The second barrier is: things have price tags. And when you are early in market it’s going to cost more,” Jeans said. For him, that’s why the Inflation Reduction Act’s funding opportunities matter — to bridge gaps and act as a catalyst to create markets.

“This is every bit a decisive decade for us,” Jeans said. “We need to reduce emissions and begin to make a turn by 2030.”

Global greenhouse gas emissions need to be slashed by 43% by 2030 to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported last year. And global greenhouse gas emissions need to peak before 2025 to limit warming to either 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius. The world is already experiencing the impacts of climate change, but limiting emissions can help avoid the worst consequences.

Funding under the Inflation Reduction Act will call for reports to the EPA or other agencies. And grants to nonprofits like Growth Opps generally require reports on how funds were used. For Jeans, though, success is about more than reports.

“Our impact is our measure,” he said. “How those whom we serve are better off is how we measure significant return on investment.”

Editor’s note: Growth Opportunity Partners receives support from the George Gund Foundation, which also provides funding to the Energy News Network. Foundations and other donors to the Energy News Network have no oversight or input into the editorial process and may not influence stories. More about our relationship with funders can be found in our code of ethics.

The following commentary was written by Charles Hua, policy analyst at Rewiring America; Ana Sophia Mifsud, a manager within the Rocky Mountain Institute’s (RMI) carbon-free building team; and Robin Lisowski, managing director of policy at Slipstream. See our commentary guidelines for more information.

The Inflation Reduction Act is an unprecedented investment in clean energy and provides a transformative opportunity for Michigan to move toward a healthier, more affordable, and safer future.

By signing this groundbreaking bill into law last year, President Biden directed nearly $400 billion in federal funding for climate initiatives through a mix of tax incentives, grants, and loan guarantees. Depending on household income, Michigan residents can take advantage of tax credits — and soon up to $14,000 in rebates — for making homes less dependent on fossil fuels and more efficient, including technologies like heat pumps and insulation.

But still, states like Michigan have a huge role to play by leveraging these millions in federal funding to invest in clean energy and ensure households are powered by resilient, healthy, and affordable sources of energy.

Michigan has already taken steps toward securing the benefits of clean energy. In 2020, Governor Whitmer committed the state to economy-wide carbon neutrality by 2050. A year later, the state developed the MI Healthy Climate Plan (MHCP) that charts a path to reach a goal halving emissions by 2030. Just last week, Governor Whitmer was one of the 25 members in the bipartisan coalitions of the U.S. Climate Alliance who committed to collectively reach 20 million residential electric heat pump installations by 2030 — potentially quadrupling the number of residential heat pumps currently in operation. The state legislature is currently considering implementing a clean energy standard, which could single-handedly put Michigan over three-quarters of the way to its 2030 climate goals.

Unfortunately, bad faith actors determined to keep homes reliant on inefficient and dirty energy sources would have you believe that Michigan lawmakers are wheeling and dealing behind closed doors to ram through sustainable initiatives without any public debates. But nothing could be further from the truth.

The Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy has been soliciting feedback from the public on implementation priorities for the MHCP, and Governor Whitmer has already signed several bipartisan pieces of climate legislation into law.

The benefits these clean energy initiatives will bring to Michigan households can’t be understated.

This June, Michigan paid the 11th highest rate for energy in the country: 19 cents per kilowatt per hour — well above the national average. This is even more harmful to low-income communities. While the average Michigan household spends 3% of its annual income on energy, low-income households spend upwards of 15%. Furthermore, in the Midwest the cost of fossil fuel expenditures for heating has steadily increased since 2019. We can expect for fuel costs to continue to increase in Michigan. A recent analysis of Michigan’s gas utility, Consumer Energy, which provides gas service to nearly 2 million Michigan households, predicts that gas bills will increase 49% in 2030 compared to 2021. This is partly because the utility plans to spend $11 billion in infrastructure investments in their gas distribution system between now and 2030.

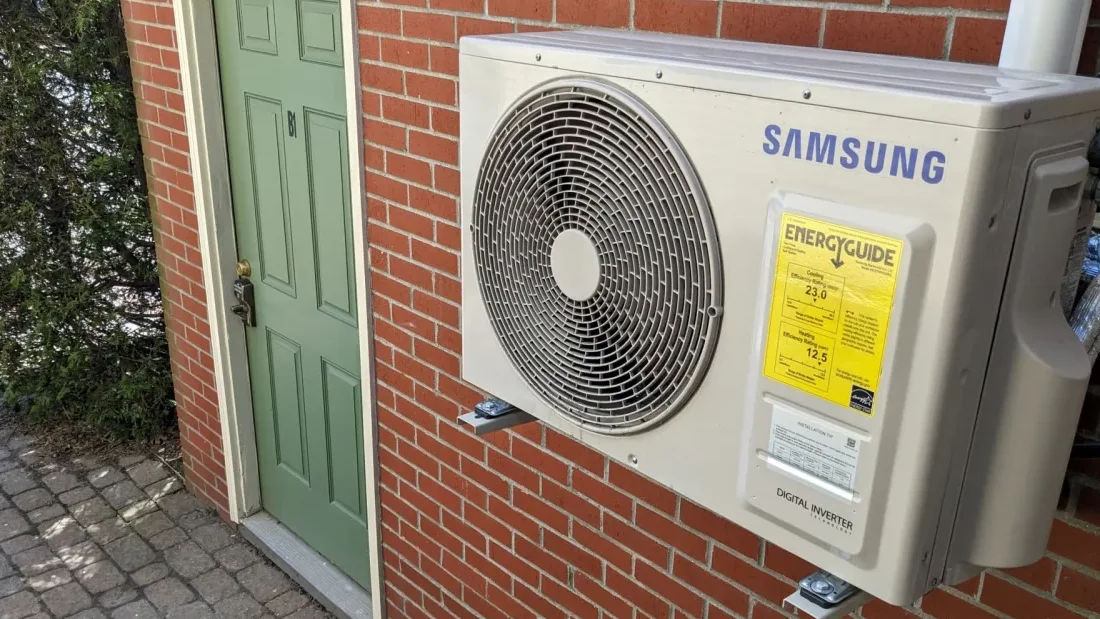

By installing a heat pump, which can both heat and cool a home using electricity, the Department of Energy estimates that many American households can save significantly on operating costs. Households will have one appliance that does the job of both a fossil fuel heating system and a traditional AC unit — and does both jobs better. Heat pumps are more effective at maintaining a comfortable and consistent temperature, even during peak summer or winter days, and are 3 to 5 times more efficient than most fossil fuel heating systems. Households that heat with delivered fuels, like propane, are expected to benefit most.

Induction stoves are also safer than gas options. Induction stoves are also safer than gas options. 12.7% of childhood asthma cases in the US are linked with emissions from gas stoves, and cooking for just one hour can aggravate the condition. In fact, 75% of emissions from a gas stove — including the carcinogen benzene — leak even when the stove itself is off.

Of course, Michigan will have to build out the infrastructure to support carbon neutrality by 2050. But doing so will mean jobs. Since the IRA was signed a year ago, nearly 200,000 clean energy jobs have been created in the Great Lake State to support electric vehicle manufacturing alone. In fact, the state is predicted to see a GDP growth increase of 2.5% above the current baseline growth rates by 2050 as a result of the clean energy jobs and IRA investments.

Clean energy is the future Michigan residents want. More than half of Michiganders supported the IRA when it first came out, and a whopping 71% wanted the state to secure more federal dollars. A poll released in April showed 73% of Michiganders want their government to do more to keep energy bills affordable — and these federal incentives offer a distinct opportunity to do just that.

Federal funding offers the state a huge opportunity to bring in long-term jobs and help households switch to safer, more affordable, and more efficient appliances. It’s the future that all Michiganders deserve.

This article was originally published by Maine Monitor.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the tax relief for heat pumps and other home energy saving projects that is available under the Inflation Reduction Act. One aspect of the IRA incentives is a rebate for heat pumps and other home electrification projects that is still being finalized by the state. The story also misstated a rebate available for small scale home sealing and other do-it-yourself projects. That rebate has expired.

Venus Nappi strolled through a community center in South Portland in early April, chatting with vendors at Maine’s annual Green Home + Energy Show about electric heat pumps, solar power, and the discounts that aim to make these and other technologies affordable. A worker in an oversized plush heat pump costume waved a gloved hand nearby.

Nappi heats her Gorham home with oil, as do 60% of Mainers — more than any other state, as The Maine Monitor reported in the first part of this series. She finds oil to be dirty, inconvenient and expensive. Her oil costs this winter, she said, were “crazy, absolutely right up through the roof.”

Nappi joined a record-breaking crowd at this expo because she’s ready to switch to heat pumps, which can provide heating or cooling at two or three times the efficiency of electric baseboards and with 60% lower carbon emissions than oil, according to Efficiency Maine.

“It’s good to have incentive to try to go somewhere else rather than just the oil,” Nappi said. “Even gas, propane, is actually a little expensive right now, too. The heat pumps are kind of in the middle.”

Government rebates of up to $2,400, with new tax breaks coming soon, help with up-front heat pump installation costs that can range above $10,000. These incentives have helped put Maine more than 80% of the way to its 2019 goal — now a centerpiece of the state climate plan — of installing 100,000 new heat pumps in homes by 2025, and many more in the years after that.

“This is a real highlight of our climate action,” said state Climate Council chair Hannah Pingree. The state aims to have 130,000 homes using one or two heat pumps by 2030 and 115,000 more using “whole-home” heat pump systems, meaning the devices are their primary heating source.

But Maine lags much further behind on a related goal of getting 15,000 heat pumps into low-income homes by 2025, using rebates from MaineHousing. At the end of last year, it had provided just over 5,000 heat pumps to the lowest-income homes.

These homes face particular barriers to maximizing the benefits from this switch — from poor weatherization, to navigating a daunting web of incentives, to fine-tuning a blend of heat sources that can withstand power outages and actually save money instead of driving up bills.

As fossil fuel costs remain high, the pressure is on for advocates and service providers to expand access to heat pumps and other strategies for reducing oil use, especially for people most often left out of the push for climate solutions.

In Maine and beyond, it’s clear that heat pumps are having a major moment — heralded in national headlines as a crucial climate solution that successfully weathered a historic cold snap.

But the technology is not new. It’s long been used in refrigerators and air conditioners.

“The problem was, when you design a heat pump to primarily provide cooling … it is not optimized for making heat,” said Efficiency Maine executive director Michael Stoddard. “So everyone concluded these things are no good in the winter. And then around (the) 2010, ’11, ’12 timeframe, the manufacturers started introducing a new generation of heat pumps that were specially designed to perform in cold climates. … It was like a switch had been flipped.”

Maine has offered rebates for heat pumps ever since this cold climate technology emerged. Even former Gov. Paul LePage, a Republican who frequently opposed renewable energy and questioned climate science, installed them in the governor’s mansion and told The Portland Press Herald in 2014 that they’d been “phenomenal” at replacing oil during a cold snap.

Heat pumps provide warmth in cold weather the same way they keep warmth out of a fridge — by using electricity and refrigerants to capture, condense and pump that heat from somewhere cold to somewhere warmer. Simply put, they squeeze the heat out of the cold air, then distribute it into the home.

The current generation of heat pumps will keep warming your home even if it’s around negative 13 degrees out.

Heat pumps are less efficient in these colder temperatures, requiring more electricity to make the same heat. With outdoor temperatures in the 40s and 50s, today’s typical cold-climate heat pumps can be roughly 300 or 400% efficient — tripling or quadrupling your energy input.

As temperatures drop into the teens, heat pumps are often about 200% efficient. And in the single digits or low negatives, heat pumps can be closer to the 100% efficiency of an electric baseboard heater. Costs at this level are closer to that of oil heat, which usually has about an 87% efficiency rating.

This means heat pumps often generate the most savings and are most efficient when temperatures are above freezing, or when used to provide air conditioning in the summer — something Mainers will want increasingly as climate change creates new extreme heat risks.

“During the shoulder seasons, you can definitely use a heat pump. When it’s wicked cold out, then you’d probably turn on your backup fuel. That’s not the official line of Efficiency Maine Trust, but a physical and engineering reality,” said energy attorney Dave Littell, a former top Maine environment and utilities regulator whose clients now include Versant Power — which, along with Central Maine Power, now offers seasonal discounts for heat pump users.

This is a relatively common approach among installers, such as ReVision Energy, a New England solar company that also sells heat pumps. They don’t recommend heat pumps as the only heating source for most customers, especially those who live farther north, unless the home can have multiple units, excellent insulation, and potentially a generator or battery in case of a power outage — a costly package overall.

“(Heat pumps) do still put out heat (in sub-zero weather), but less, obviously, and they have a lot more cold to combat in those conditions,” said Dan Weeks, ReVision’s vice president for business development. “Generally … we do recommend having a backup heating source.”

These blends of heating sources are nothing new in Maine — many families combine, say, a wood stove with secondary heat sources that rely on propane, oil or electricity. Experts say heat pumps are a powerful addition in many cases, adding flexibility and convenience.

Heat pumps will add to your electric bills but also reduce another expense that’s eating up a lot of household budgets — heating oil. Instead of spending hundreds to fill your tank just as winter starts to wane (a full 275-gallon tank would run more than $1,000 right now), you might be able to switch entirely to your heat pump in early spring. Vendors say a heat pump will be much more cost-effective than fossil fuels for the vast majority of Maine’s heating season.

One study from Minnesota — which has lower electric rates and more access to gas, but has made a similar push for heat pumps — found the greatest savings from using a heat pump for 87% of the heating season, switching to a propane furnace only below 15 degrees.

Electricity costs also change less frequently than fossil fuel prices. And the advent of large-scale renewable energy projects, like offshore wind, aims to help smooth over rate hikes that are now driven by the regional electric grid’s dependence on natural gas, said Littell of Versant Power. (While Maine has little gas distribution for home heat, New England power plants use a lot of it to make the electricity that’s primarily imported to Maine on transmission lines.)

This will also mean the electricity that fuels your heat pump will be even lower-emissions than it is now. The emissions comparison between heat pumps and oil is based on the current New England electric grid’s carbon footprint, which is set to continue shrinking.

Paige Atkinson, an Island Institute Fellow working on energy resilience in Eastport, pitches heat pumps as a good addition to a home fuel mix. But she said all these cost comparisons can cause anxiety for people unsure about switching. Oil costs, though rising and prone to fluctuations, can be a “devil you know” versus heat pumps, she said.

“Transitioning to an entirely new source of heat creates a lot of ‘what-ifs,’ ” she said. “There’s a lot of uncertainty about how to best use that system — will it meet my needs?”

The best way to guarantee savings from a heat pump is likely to work closely with your contractor about where to install it, and when and how to run each part of your home’s fuel mix.

“Our job is to educate (customers) on proper design, proper sizing, best practices for installation,” said Royal River Heat Pumps owner Scott Libby at the South Portland expo. “I always tell people to use the heat pump as much as possible. … If you are starting to get chilly, that might just be for a couple hours in the morning when the temperature outside is coldest, so maybe use your fossil fuels just to give the system a boost in the morning, for even an hour.”

The condition of your house is another big factor in the heat pump’s performance.

“Weatherization is a great tool. It is not necessary to make a heat pump work … but the heat pump will work better if the house is well weatherized,” said Stoddard with Efficiency Maine. “When you have those super, super cold days, it won’t have to work as much.”

The need, ideally, for updated insulation and air sealing as prerequisites for heat pumps may help explain the slower progress on getting them into low-income homes. (We’ll address heat pumps as a potential benefit for renters later in this series.)

“I think a lot of the homes especially that (qualify for rebates from) MaineHousing … require a lot of upgrades, just sort of basic home improvements, to get to the next step,” said Hannah Pingree of the state Climate Council.

Bob Moody lives in the kind of house Pingree is talking about in Castle Hill, a tiny town just outside Presque Isle. The ramshackle clapboard split-level totals four stories, set into a wooded hillside. Moody grew up down the road, and his family built this place in the 1980s using much older scrap materials from the former Loring Air Force Base in Caribou.

On a snowy day in March, Moody was visited by a small team from Aroostook County Action Program, or ACAP. It included his next-door neighbor, ACAP energy and housing program manager Melissa Runshe. She and her colleagues were there for an energy audit, a precursor to weatherization projects — all paid with public funds through MaineHousing.

“Weatherization is at the very top. If your heat isn’t flying out of your house, it’s going to save you money,” Runshe said. “We have a lot more winter here (in Aroostook County) than in the rest of Maine, so it’s really important to make sure that the houses are energy-efficient — so that they’re not burning as much oil, so that they’re not spending as much money on oil.”

ACAP officials said they don’t push any technology over another when meeting new clients, but instead describe the options and benefits — savings, comfort, a smaller carbon footprint. This all typically happens after someone has called for heating aid or an emergency fuel delivery — or, in Moody’s case, an emergency fix for their heating equipment.

Moody’s health forced him to retire early, and he now lives alone on a low fixed income. He’s gotten energy assistance and upgrades from other state and county programs before, but first called ACAP late last year when his main heat source, a kerosene furnace, suddenly died. ACAP got him a new, more efficient oil furnace, then signed him up for a weatherization audit.

“If it hadn’t been for assistance, I would have been really in trouble,” Moody said as he filled out paperwork at his kitchen table. A sticker on the wall proclaimed Murphy’s Law — anything that can go wrong, will. “Murphy has been settling in very heavily on me,” he laughed.

Moody’s ACAP audit included a blower door test, which depressurizes the house to expose air leaks. They showed up on a thermal imager as cold seeping in through window seams, power outlets, hairline cracks in the walls, and most of all, an uninsulated exterior-facing wooden door that was down the hall from Moody’s new furnace, sucking heat from the rest of the house.

“He has, roughly, a (total of a) one-by-two-foot-square hole that’s wide open in the house,” said energy auditor BJ Estey. “It’s basically like the equivalent of having a window open year-round.”

The inspection showed weatherization could save Moody $1,230 a year on oil. New windows and doors would help even more — but the weatherization program doesn’t offer those, and there’s a 900-person waiting list for ACAP’s program that does. Instead, the staff told Moody to try a federal option for home repair grants and loans, and promised to help him with the forms.

For people who don’t receive MaineHousing-funded upgrades, Efficiency Maine offers healthy rebates for air sealing and insulation performed by contractors. Last winter it also added a small new rebate for do-it-yourself home weatherization, such as plastic wrap for windows, pipe wraps and caulk, which has since expired.

Groups like ACAP also offer free heat pumps for low-income residents using MaineHousing funds. The rebates feed the state’s goal, where progress has been slow.

Moody has one kind of heat pump in his home but it’s not the type that provides hot air — it’s a heat pump-based hot water heater, which he got for free through a rebate from Efficiency Maine. He loves the savings and convenience it’s provided.

But he doesn’t think an air-source heat pump — the kind that can replace an oil furnace — will work for his home, which has many small rooms split up across levels. (Installers often recommend at least one heat pump per floor.) He’s also worried about how a heat pump would affect his electric bills. He knows he couldn’t afford electric baseboard heat, so he’s concerned about the very cold conditions where a heat pump’s efficiency drops down to around that level.

“Sometimes in the middle of the winter, you get so cold that you just might as well have an electric (baseboard) heater,” he said. “And there ain’t no way that I can afford an electric heater — not even one month.”

Down the road in Castle Hill, Melissa Runshe’s newer-construction house came with three heat pumps, a boiler that can use wood pellets or oil, and a propane fireplace. “I think (heat pumps) are wonderful,” for heating when temperatures are above about 20 and for summer cooling, she said. “They definitely offset the cost of my oil.”

While not every house is heat pump-ready, it may be even more important to get folks like Moody connected with this energy safety net in the first place. This will continue to decrease his oil dependence, offering escalating upgrades as his home changes and funding sources shift.

“In the social services world, there’s this idea of ‘no wrong doors,’ and we need to adopt that for home energy as well,” said Maine Conservation Voters policy director Kathleen Meil, the co-chair of state Climate Council’s buildings group. “There’s no distilling and simplifying how people live in their homes. You experience your house and your home’s heating situation not as a data point, but as your daily life.”

For people like Meil, there are multiple goals working in tandem — help Mainers reduce their reliance on planet-warming fuels like heating oil, while helping them lower household energy costs, and live with more comfort and convenience. This is what climate advocates mean when they say the crisis is “intersectional” — it’s interwoven with health, race, poverty and more.

Juggling these issues can mean making more incremental progress toward emissions goals — but that’s far better than nothing in scientific terms, said Ivan Fernandez, a professor in the University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute.

“Everything we do, every increment we do, counts,” Fernandez said. “I think we need to do this transition in a relatively quick way, recognizing that it will be imperfect, and spending a good part of our focus on realistic, data-driven, science-driven tracking of where we are at, so we’re not telling ourselves fables that aren’t substantiated by the science.”

Officials say Maine used this kind of science in building detailed goals for things like heat pump adoption, adding them up toward a path to the two biggest targets that are inked in state statute — reducing emissions 45% over 1990 levels by 2030 and 80% by 2050.

“Ultimately the atmosphere will determine how successful we are. It’s already telling us that we have not been very successful in many ways,” said Fernandez. “But … I think we’re embracing the reality of that a lot better.”

Setting these goals carefully and pushing hard to meet them does not guarantee equity — and there are still holes in the state’s approach, according to people working on spreading the benefits of the energy transition to those who might not be able to access it without help.

The Community Resilience Partnership, or CRP, is the state’s signature grant program for town-level climate action. Each project starts with a local survey to determine residents’ priorities out of a 72-item list that includes everything from flood protection to energy efficiency.

State officials say the CRP was designed primarily to build up towns’ capacity to respond to climate change. But advocates say they’ve had to work around a crucial gap in the program: It won’t buy equipment directly for individuals, which is often what people say they want the most.

“There are communities who really do have the need to fund heat pumps beyond what Efficiency Maine is providing,” said Sharon Klein, an energy consultant and University of Maine professor who works with Maine tribes on their CRP projects. “Because there’s still that last piece of it where money still needs to be put up, and some people don’t have that money.”

For people whose income is not quite low enough to qualify for a totally free heat pump through MaineHousing, Efficiency Maine’s rebates will cover $2,000 for a first unit and $400 for a second. People at any income level can get $400 to $1,200 for one or two units. This might cover some or all of the cost of a typical single heat pump — but total installation costs can range from around $4,000 to above $10,000, depending on the complexity of the system.

Starting this tax year, the Inflation Reduction Act will offer new tax credits of 30% for heat pumps, up to $2,000 per year. The IRA will also provide additional rebates to cover heat pumps and other home electrification projects, but the details of those rebates are still being finalized. The IRA allows states to, in theory, offer as much as 100% of project costs up to $8,000 for low-income families, or 50% of costs for moderate-income families — but state officials are still deciding how exactly this limited pot of money will be used and who will be eligible. The rebates will not be universal or unlimited, said Stoddard with Efficiency Maine, but should benefit several thousand homes.

Dan Weeks of ReVision Energy said increasing availability of low- or no-interest loans is another priority for those who want to see more people switch from oil to efficient electric heat. The IRA will help Maine expand its Green Bank in the next year or so to “start offering financing to particularly low-income folks and folks with poor credit,” Weeks said.

But tax credits and cheap loans are still deferred ways of helping people lower their oil costs and cover those remaining heat pump costs. Downeast CRP coordinator Tanya Rucosky, who works on community resilience for Washington County’s Sunrise County Economic Council, said many families simply can’t afford to make the switch.

“Folks need just a little bit of seed money,” she said. Without more support, “it locks out the people that potentially need it the most.”

Atkinson, the Island Institute Fellow, said Eastport found a creative way to offer direct funding within the constraints of its CRP grant. People who participate in the city’s peer-to-peer energy coaching program, Weatherize Eastport, can get another $2,000 toward heat pump installation.

“They’re agreeing to become almost ambassadors for this program. One of the steps to do that is to volunteer some time,” Atkinson said. “The city is compensating these residents for their time involved in this partnership, rather than saying, we will just give you funds for X, Y and Z.”

Solutions like this are key to ensuring these tools for moving off oil can grow equitably, said Rucosky — helping more people to join the transition and spread the gospel of its benefits.

“Especially for Mainers — they’re so salty and smart. They’re like, ‘What’s the catch?’ So I don’t think there’s any getting around the labor of it,” Rucosky said. “The more people have successful experiences doing this, the more I don’t have to be the one saying it …and it can be like, Bob down the road. And so it builds — but it takes a long time to build that, where everybody knows this is how you get this done. That’s going to be years in the making.”

This article is co-published by the Energy News Network and Planet Detroit with support from the Race and Justice Reporting Initiative at the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights at Wayne State University.

It’s that time of the year for reflection, whether personally or, in James Gignac’s case, on the progress Midwest states have made in pursuing clean energy goals.

Gignac is the Senior Midwest Analyst for the Climate & Energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. He shared with Planet Detroit some additional thoughts from his recent post about milestones reached by Michigan and its neighbors.

Q: Consumers Energy has a proposed plan that will come up for approval before the Michigan Public Service Commission in 2022. That plan includes burning natural gas. How can the MPSC hold utilities accountable for those proposed actions?

A: The utilities in Michigan, including Consumers Energy, are obligated to display ways to provide the lowest cost, cleanest and reliable energy for their consumers in the state using an Integrated Resource Plan.

While Consumers Energy has some really good features in their pending plan, including phasing out all of the coal plants by 2025 and making large investments in solar, there’s also the question of the role of methane gas, which is sometimes called natural gas.

The question is, what is the role of gas in their future resource plan? What Consumers Energy is trying to do is begin to map out how it will achieve the carbon reduction goals that it as a company has established.

While they’re not proposing to build new gas plants, they’re proposing to acquire existing gas plants. And what we and other advocates are concerned about is the transition away from coal and towards clean energy. Investing in gas resources is risky for customers because those gas plants could very quickly become uneconomic or unneeded.

And so while it’s good that the company is not wanting to build a new gas plant – which most utilities are moving away from, it’s still concerning from an economic perspective and because they still produce carbon emissions and other pollutants.

One of the facilities in particular concerns environmental justice advocates. Testimony submitted by our stakeholder coalition and others, highlights the environmental justice concerns of existing natural gas plants.

Q: What other items should we watch out for in Michigan in 2022 you’d like to highlight?

A: In 2021, especially in Michigan, we saw the increasing interest in demand from communities and customers to have greater control and greater amounts of locally-owned clean energy resources. We’re beginning to move away from the traditional model of utilities providing electricity to customers from faraway power plants.

DTE Energy will be filing an Integrated Resource Plan in the Fall of 2022, which is a year earlier than planned. The upside of that is that we will have a chance to look at DTE’s newest proposals a year earlier than expected. That’s important because we need to be moving quickly, and we need to urge utilities to continue taking rapid steps in a clean energy transition.

So looking ahead to 2022, the DTE Integrated Resource Plan and the important opportunity to review those current plans.

I’m also looking forward to seeing a strong action plan from the Council on Climate Solutions. Last year, Governor Whitmer’s executive order, the Council on Climate Solutions, has been working to develop an action plan to reach the state’s carbon reduction goals. We’ll see that quickly in 2022 as a draft will be released in mid-January, and the Council will then finalize that in February and March.

We’re hopeful that the document will be a strong plan for Michigan and include immediate and near-term steps that can be taken and lay out a long-term action plan for additional policies that can be put in place.

We also will have a Consumers Energy decision on its Integrated Resource Plan. So we’re hopeful that the Public Service Commission will approve the company’s plans to retire its coal plants and pursue its solar expansion. And ideally, either postpone or not approve all of the existing gas plants for acquisitions. So if there’s an opportunity to evaluate those further or ask the company to do some additional analysis to ensure cleaner energy options could be pursued instead of those gas plants.

And in Michigan’s legislature, I think it’s important to continue focusing on and discussing clean energy legislative proposals and to build the demand for taking action at the legislative level.

Q: There was a recent major win for Illinois – anything you want to share about it?

A: The Climate and Equitable Jobs Act (CEJA) was based on building upon and expanding previous legislation, so in 2017, Illinois passed the Future Energy Jobs Act. What advocates started doing immediately after that legislation passed was starting to think about the next set of policies that can be passed in Illinois, while identifying things that needed to be improved or changed from the 2017 legislation.

CEJA was the product of many conversations and discussions amongst a broad set of stakeholders, which led to its passing in 2021.

Centering the needs of lower-income communities and making sure that clean energy investments and benefits are shared amongst all Illinois communities is a key to making them a leading national leader in the equitable pursuit of clean energy and climate action.

Q: What else should Michigan consider in 2022 related to clean energy advocacy and policymaking?

A: I would say that crafting clean energy policies centering people and lower-income, traditionally disadvantaged communities. Doing that is important, but it’s also popular. People want to see equity being a key part of clean energy and climate responses.

So I think our work in 2021 really highlighted that and we have an increasing amount of good examples to draw from, whether it’s Illinois’ efforts or programs in other states that can be applied in Michigan and elsewhere.

Q: What’s next for UCS?

A: We’re looking to follow up on our Let Communities Choose Report in partnership with Soulardarity. In Highland Park, we’re working on analyzing a microgrid for the Parker Village neighborhood in Highland Park. So that would be an additional piece showing the potential for local clean energy.

We partner with many other groups doing great work in Michigan and at the state level, advocating the Council on Climate Solutions and the Michigan Public Service Commission.

Refunds for unlawful utility charges are a top priority for Maureen Willis, the veteran litigator who became Ohio’s new consumers’ counsel this month.

The Office of the Ohio Consumers’ Counsel is a state-funded agency that represents ratepayer interests in gas and electric utility cases, including matters relating to House Bill 6, the 2019 law at the heart of Ohio’s nuclear and coal bailout scandal. The office also works for legislative reform to promote competition, eliminate subsidies and protect energy affordability for vulnerable groups.

The Energy News Network spoke with Willis about her agenda as Ohio’s official advocate for residential ratepayers.

“If consumers are charged and there’s a decision by the court or even a federal agency that the charges were unlawful or unreasonable, we think they should get the refund all the way back to when they paid it,” Willis said.

Instead, a majority on the Ohio Supreme Court has held that a 1957 case against “retroactive rulemaking” forbids refunds of charges, called riders. That’s the case even if the court holds the charges are otherwise unlawful or unreasonable and even if the riders were not part of a full ratemaking case.

So, even though the Ohio consumers’ counsel has helped consumers avoid $433 million in charges since 2009, they’re still out $1.5 billion in refunds. That makes the wins something of a “hollow victory, because you’re not getting that money back,” Willis said. “But we will continue to fight.”

“We want to advocate for consumers to get energy at the least cost,” Willis said, noting the agency generally considers itself agnostic on the source of electricity. Nonetheless, “renewables are becoming more and more economic, and that certainly is something that we take into account in the mix,” Willis said.

A 2023 report by Energy Innovation Policy & Technology found that 99% of U.S. coal plants are more costly to keep running than replacing them with new solar, wind or energy storage.

Yet HB 6 and regulatory rulings before it require Ohio ratepayers to subsidize costs for two 1950s-era coal plants. OCC continues to contest those charges.

“To the extent that there are subsidies built into the rate and those subsidies are attached to monopoly rates, it creates a problem” by undermining the market, Willis said. “In Ohio, we do rely on the competitive market to bring consumers lower prices and greater innovation.”

“From our perspective, energy efficiency is a good thing,” Willis said, noting that it can help reduce people’s utility bills. Ten years ago, Ohio law required utilities to meet an energy efficiency standard. Back then, OCC was among parties pushing regulators to require FirstEnergy to bid that energy efficiency into a capacity market auction, which lowered costs to consumers. But in 2019, HB 6 gutted Ohio’s energy efficiency standard.

Now, though, consumers can get energy efficiency products and services from competitive suppliers, Willis said. So, “we would say that the utility really has no business to be in the energy efficiency business anymore.” OCC also objects to “shared savings,” which it views as extra profits for utilities.

A bipartisan bill to let utilities run voluntary energy efficiency programs is pending in the General Assembly. Supporters say utility-run programs can make savings simpler for consumers and can produce benefits for all ratepayers by reducing system-wide demand.

OCC has “always battled” electric security plans, or ESPs, Willis said. “We believe they are crony capitalism.”

A traditional ratemaking case requires utilities to show all their projected costs and revenues, based upon actual data from a representative test year. ESP cases don’t require that detailed scrutiny. They allow utilities to raise rates for isolated issues, without presenting those charges in the context of all of a company’s financial activities. And utilities can reject any change regulators might try to make to a plan — effectively giving them unequal, outsized bargaining power, Willis said.

Along those lines, OCC supports Senate Bill 143, which would get rid of ESPs and strengthen corporate separation between utilities and their affiliates.