President Donald Trump’s crusade against wind energy is intensifying — and it could come with some serious costs.

As much as $317 billion in lost investment, to be exact, per new analysis from research firm Cleanview. That figure is based on the 790 projects totaling 213 gigawatts that developers plan to build in the years to come — all of which are at risk of delay or even cancellation under the administration’s policies.

To be clear, those figures represent the high end of what’s at stake — they’re based on what’s currently in the interconnection queue, and projects drop out of that process all the time for various reasons.

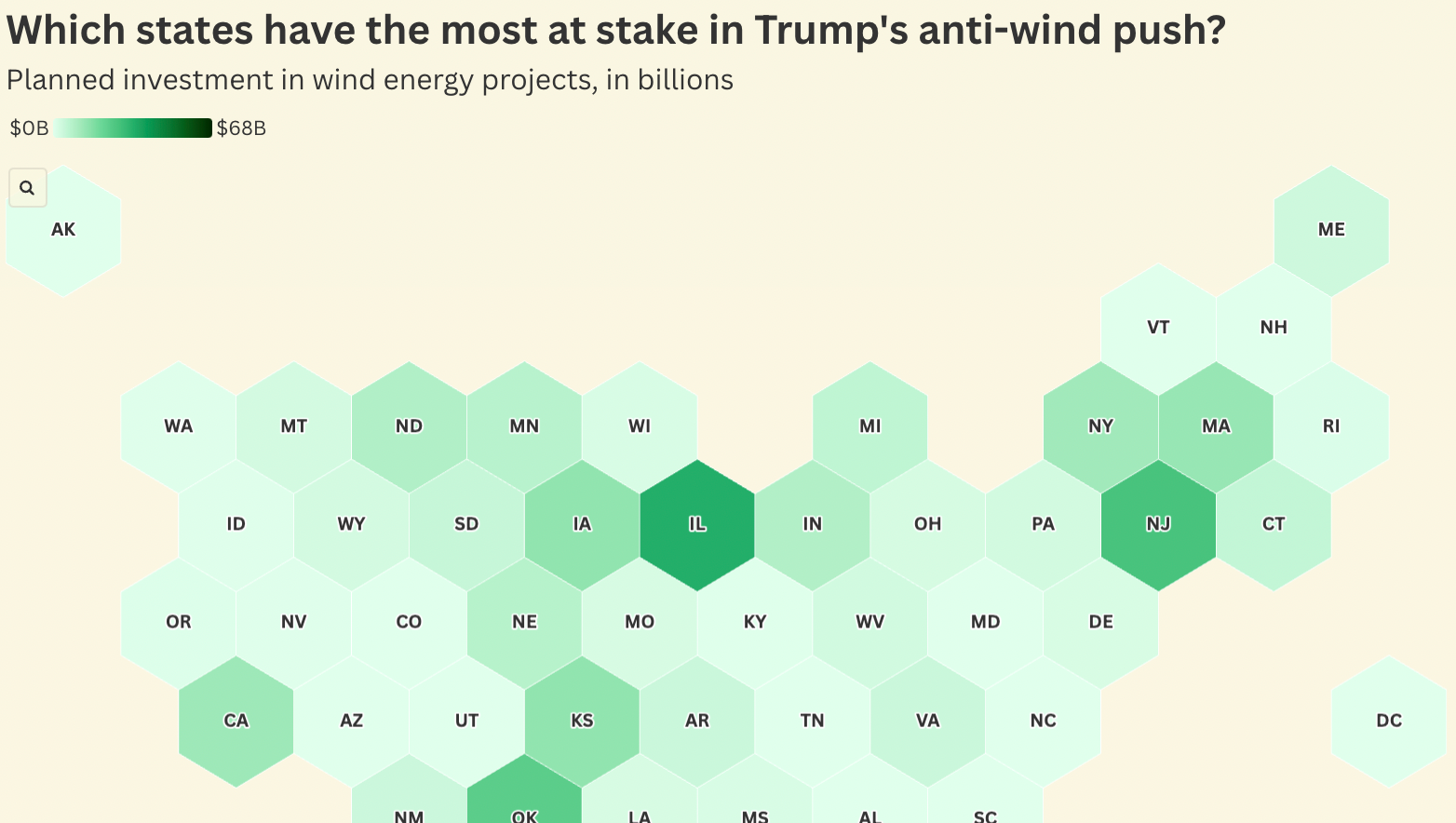

But if even a fraction of that investment is canceled or delayed, it will be painful for the regions that miss out on the tax revenue and jobs, with Texas, Illinois, and New Jersey standing to lose the most.

It would also be bad timing: Electricity demand is on the rise nationwide, largely due to the boom in AI data center construction. Delaying or blocking the buildout of gigawatts worth of wind projects when the U.S. is in the midst of an energy-supply crunch would drive up already-climbing power bills. Wind produced just over 10% of U.S. electricity last year.

And, of course, any slowdown in the construction of clean energy is a setback for efforts to transition the U.S. away from fossil fuels, a task that grows more urgent with the passage of every hot summer day.

Trump entered office in January with promises that not a single new “windmill” would be constructed during his second term. Though he’s not managed to carry out that vision in its most literal sense, he has certainly operated with its spirit in mind.

On his first day, he issued an executive order calling for an end to offshore wind leasing and a review of leases and permits for all wind projects. In the spring, Trump tried — and ultimately failed — to quash the Empire Wind offshore installation that had just begun construction near New York’s coast. After GOP lawmakers rammed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act through Congress, Trump signed the megalaw on July 4, mandating the swift phaseout of tax credits for wind (and solar) projects.

In recent weeks, his administration has stepped up its attacks even further and undertaken an all-out blitz on wind power, issuing a barrage of far-reaching orders that, at least in theory, could jeopardize every wind project underway in the country.

State leaders and clean energy groups across the country are pushing to build more wind and solar projects before the window to claim federal tax credits slams shut.

The new GOP megalaw rapidly phases out incentives for clean energy, years before the Biden-era tax credits were set to lapse. The shortened timeline is expected to slow the construction of wind and solar projects at a moment when states are grappling with soaring power demand that is raising both utility bills and greenhouse gas emissions.

Many local lawmakers and utility regulators were already working to modernize their grids and streamline energy permitting before President Donald Trump signed the budget bill last month. Recently, decision-makers in a handful of places have taken steps to expedite those efforts so that more large-scale renewables projects can qualify for the tax credits before they expire.

Under the megalaw, wind and solar farms must either start construction by July 4, 2026, or be placed in service by Dec. 31, 2027, to qualify for the full production or investment tax credits. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act previously allowed developers to access credits if they began construction either by 2033, or by the time the U.S. power sector cut emissions by 75% compared with 2022 — whichever came later.

For states, “The question then becomes, what can they do to try to maximize the benefits they’ll get from those [clean] technologies between now and then — the jobs, clean air, and power?” said Nathanael Greene, director of renewable energy policy for the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC).

In Maine, state utility regulators have responded by fast-tracking plans to procure nearly 1,600 gigawatt-hours of renewable energy, so that projects can get started before tax credits phase out. Residential and community solar developers in California’s Orange County and Minnesota say they’re focused on installing as many solar arrays as they can, including by tapping into state and municipal incentives that still remain.

Meanwhile, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul (D) has directed state energy regulators to conduct “a high-level review” of the budget law and its “specific impacts to New Yorkers.” However, clean energy developers in the state are calling for more specific actions to expedite wind and solar development, such as speeding up the yearslong process for issuing construction permits and improving coordination among state agencies.

For now, Colorado Gov. Jared Polis (D) is the only state leader to issue an executive action to prioritize deployment of clean electricity projects in response to Trump’s budget law.

Earlier this month, Polis penned a letter that directs state agencies to “move quickly and secure success” for large-scale wind, solar, and battery storage resources, as well as community solar projects. The letter calls for eliminating “administrative barriers and bottlenecks” and “prioritizing expeditious review of projects as they come into the queue for state consultation and permitting.” It also raises the idea of invoking the Public Utilities Commission’s authority to override local permit denials.

“When we look at the new generation that is being built in Colorado, the vast majority of it is wind and solar,” Will Toor, executive director of the Colorado Energy Office, told Canary Media. “Getting as many projects as possible able to move forward on a timeline that allows them to receive those [tax] credits is very much in the interest of the state — not only for clean energy goals, but very much for reducing costs to ratepayers.”

Alana Miller, who leads NRDC’s climate and clean energy policy team in Colorado, said the governor’s letter “is a key first step and provides a lot of urgency at this specific moment.” Still, “There’s a lot to be seen how it plays out and how agencies actually implement it,” she said, noting that state legislative action could follow next year.

In Colorado and beyond, officials are largely waiting to outline more concrete plans until the Treasury Department issues its new tax-credit guidance, which is expected to tighten the rules on which projects can claim incentives. Policy experts say they’re watching closely to see how the leaders of other major energy-producing states, including Pennsylvania and California, step in to support renewables in their backyards.

In June, Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro (D) warned legislators that the House’s version of the budget bill — which proposed even deeper cuts to clean energy incentives than the final version — would undermine more than $3 billion in direct investment in Pennsylvania energy projects. The impact would be most severe on the “nearest-term energy sources,” namely wind, solar, and batteries, that are coming online to meet surging demand in the state, his letter said.

Shapiro has made building “next-generation power” a key priority as power-hungry data centers strain the state’s grid and drive up electricity costs. His sweeping six-part energy strategy released in January includes policy proposals to increase the amount of electricity that comes from renewable sources in the state, and to establish a “cap-and-invest” program that reduces carbon emissions while also lowering electricity bills.

In California, a leader on clean energy deployment, the industry is urging Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) to help blunt the megalaw’s impact on utility-scale wind, solar, and energy storage developments.

Five trade groups sent a letter last month asking Newsom’s office and state legislative leaders to create a “coordinated action plan” to address the shortened tax-credit timelines, as well as the Treasury Department’s forthcoming guidance. The groups proposed steps such as streamlining environmental reviews and making it easier to build projects on agricultural land.

Another measure that California officials could immediately take is to enable wind, solar, and batteries to access “surplus interconnection” at existing gas-fired power plant sites — a concept that state legislators are currently considering.

Gas power plants in California are running less often as the state works to slash its planet-warming emissions, Mike O’Boyle, director of electricity policy at Energy Innovation, explained in a recent opinion piece in the Los Angeles Times. That leaves gas plants’ transmission wires mostly unused. Wind and solar projects could use this existing surplus to immediately connect to the grid, rather than wait years for system upgrades.

A working paper by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, estimates that this pathway could allow California to cost-effectively integrate 24 gigawatts of renewable energy capacity by 2030. For context, the state currently has nearly 90 GW of total generation capacity.

Clean energy developers in every state will need all the bureaucratic fixes and outside-the-box solutions they can get in order to maintain momentum for the energy transition. Early estimates found that Trump’s megalaw could shrink new clean capacity additions to the grid by up to 62% over the next decade compared to the baseline scenario. By 2035, national average household energy bills could be $78 to $192 higher than if Biden-era policies remained in place, according to Rhodium Group.

“We still anticipate that clean energy will be built and will likely still be able to compete [with fossil fuels] despite the headwinds,” said Miller of NRDC. But the cost of electricity will be higher without the tax incentives.

The humble streetlight doesn’t look like a particularly attractive target for theft. But in Los Angeles, a mind-boggling 27,000 miles of copper wire connect those lights to the power grid — and thieves are tearing that wire out at an alarming rate. Public employees can’t keep up with repairs, leaving frustrated neighborhoods in the dark for months on end.

The sun-drenched city has recently discovered a promising new solution: It’s swapping out traditional streetlights for solar-powered versions that are not attached to the larger power system and thus have no copper wire to steal. Instead, the new lights are equipped with batteries that fill up on solar energy during the day and discharge it after dusk falls.

“It’s been tremendously successful,” said Miguel Sangalang, executive director and general manager of LA’s Bureau of Street Lighting.

While copper-wire theft isn’t a new plight for LA, it’s become more prevalent in recent years as rising prices have made it more lucrative to sell the stolen metal. In the last decade, theft and vandalism have jumped from representing just a few percent of the Bureau of Street Lighting’s service requests to 40% today, according to a spokesperson for the department. Since 2020, the city has spent over $100 million repairing such damage. On Reddit, residents complain of “pitch black” neighborhoods that feel unsafe.

The city isn’t about to replace all of its more than 220,000 streetlights with solar. So far, it’s only deployed around 1,100 of the new fixtures, and plans to install at least 400 more this fiscal year. The Bureau of Street Lighting is still figuring out its long-term strategy, but for now, it’s focused on rolling out solar lights where they can immediately do the most good: areas with lots of theft.

“[We’re] testing it in incremental steps,” Sangalang said. “But we see ourselves going into it much harder and much faster in the near future.”

Other U.S. cities are thinking along the same lines. Clark County, home to Las Vegas, began testing solar streetlights last summer after dropping more than $1.5 million over two years to fix vandalized lights. St. Paul, Minnesota, decided to install the city’s first solar streetlights this year, fed up after spending over $2 million in 2024 on repairs only for thieves to strike again days later. San Jose, California, which had about 1,000 streetlights out due to copper theft in early July, is currently planning a pilot, pending funding availability.

These are small-scale experiments, but they still reduce planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions by introducing more clean energy into major cities. One of the solar lighting companies that LA is working with estimates that deploying 10 of its sun-powered streetlights in Europe would cut carbon emissions by 60 metric tons over four decades — the same pollution footprint as seven flights around the Earth.

Inspired by a suggestion from a field electrician, LA began testing off-grid solar lights in 2022 with $200,000 in grants from the city’s innovation fund. In early 2024, the city rolled out its first concentrated, large-scale deployment of 106 solar lights in the Van Nuys neighborhood — a hotspot for theft that is located far from the Bureau of Street Lighting’s headquarters downtown.

“We’d spend two hours on the road trying to do a repair if we had to go back and forth,” Sangalang said.

The goal in Van Nuys was to create a “maintenance-free zone,” said a spokesperson for the Bureau of Street Lighting. It’s working: In a year and a half, the department hasn’t had to deal with a single instance of damage related to theft and vandalism. Among community members, “the sentiment continues to be that they’re great and that we need to see more of them in the city,” said LA Councilmember Imelda Padilla, a Democrat who represents Van Nuys.

With that track record, the city has since rolled out hundreds more solar lights in the Watts, Boyle Heights, and Historic Filipinotown neighborhoods.

“This is one of those things where, across the board, whether you care about the environment or not, lighting is the best deterrent to crime, right?” Padilla said. “It makes it so that families and single women and children can enjoy the Southern California weather late into the night.”

For the record, LA is also taking other steps to deter copper-wire theft, such as encasing wire enclosures in concrete, replacing copper with less valuable aluminum wiring, and standing up a special police task force.

What sets solar lights apart are their benefits unrelated to theft, Sangalang said: The systems cut the city’s energy bills and can stay lit during blackouts. Plus, they each take only about 30 minutes to install on average (after prep work), since the new lighting fixture, solar panel, and battery pack are often simply attached to an existing streetlight pole.

The big catch with solar streetlights has always been their up-front cost. According to the LA Bureau of Street Lighting, a single solar- and battery-equipped lighting unit can cost around $3,250 — a huge jump from the $300 to $500 price tag for standard equipment.

It’s not easy to sell city leaders stressed about budget shortfalls on the idea of spending thousands of taxpayer dollars replacing perfectly fine grid-connected streetlights with their solar counterparts. But copper-wire theft is completely upending the calculus.

A single repair to address copper theft can cost between $750 and $1,500, Sangalang explained, meaning that “in a place where I would have had to go repair two, maybe three times, the solar light itself would have paid for itself in that same time frame.”

Despite the momentum toward solar streetlights, infrastructure-scale deployment is still just beginning in the U.S., said Hocine Benaoum, CEO of Texas-based Fonroche Lighting America, one of the companies supplying LA with solar lights.

City governments in this country are often risk-averse when it comes to new technology. Fonroche, which was founded in France in 2011, lights highways and communities around the world, but its municipal customers in the U.S. typically insist on first trying out just a handful somewhere like the back parking lot of a public works building, he said. Once they find out that works, the lights often get tested on a slightly more public site like a dog park or a pickleball court before — finally — a city feels comfortable installing them on residential streets.

“We were lighting whole countries in Africa, highways, whatever,” Benaoum said with a smile. “And in the U.S., you meet with the city manager and public works, and they tell you, ‘OK, yeah, we love your product. Let’s put it in the dog park.’ So there are a lot of dogs that are happy with Fonroche in the U.S.”

In LA, Sangalang is gaining confidence in the technology, although sun-fueled fixtures don’t yet meet the city’s brightness standards for major streets. Other areas aren’t good candidates for solar lights because tall buildings block the sun for much of the day.

Off-grid solar lights also can’t support the EV chargers and telecom equipment that LA hooks up to grid-connected lights, according to the Bureau of Street Lighting. While Sangalang is considering the potential of solar-powered lights that also feed into the grid, he said that technology is less developed.

“[Solar lights are] a great tool in the toolbox for the larger system,” Sangalang said, “understanding that you must use different tools for different places.”

Alicia Brown, director of the Georgia Bright Coalition, wants people to know that the $7 billion Solar for All program is starting to bring affordable solar power to her home state — even as the Trump administration threatens to kill it.

With the $156 million Solar for All grant the coalition won last year, it’s installing no-cost rooftop solar for low-income homeowners and expanding a two-year-old pilot program that offers low-cost solar and battery installations for thousands more residences. It’s also planning to back community solar projects and is helping finance solar and batteries at churches that promise to use the cheap power to lower utility bills for disadvantaged households and provide shelter during grid outages.

Now this program and others being actively developed by state agencies, municipalities, tribal governments, and nonprofits that received Solar for All grants are in jeopardy. The Environmental Protection Agency, which administers the grant program, is preparing to send letters to all 60 awardees informing them that their funding will be terminated, according to news reports this week citing anonymous sources.

The National Association of State Energy Officials (NASEO), a group representing the state agencies responsible for managing a large chunk of Solar for All funding, also widely circulated an email warning that the EPA could be on the brink of ending the program.

“We do not have any additional details or validation of the news that has been reported,” NASEO President David Terry wrote in the email, which was shared with Canary Media. “Yet, the information received yesterday comes from a credible source.” (NASEO did not immediately respond to requests for comment.)

Cutting Solar for All funding would be a mistake, said Michelle Moore, CEO of Washington, D.C.–based nonprofit Groundswell. Over the next five years, the program promises to deliver more than $350 million in annual electric bill savings to more than 900,000 low-income and disadvantaged households — desperately needed relief in a time of high and rising utility costs.

And the more than 4 gigawatts of solar power the program aims to bring online, much of it backed up by batteries, could help utilities across the country meet growing demand at a time when the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress have undermined the policies supporting clean energy growth.

Groundswell is using its $156 million Solar for All grant to launch the Southeast Rural Power Program, open to municipal utilities and rural cooperatives across eight Southeastern states to develop more than 100 megawatts of distributed solar and battery projects.

Those projects could cut electricity bills in half and improve local resilience for more than 17,000 households. That’s a vital source of new grid capacity for a region facing unprecedented growth in demand for electricity, Moore said.

“This country is short on power right now. We need every electron we can get,” she said. Terminating Solar for All at this stage would equate to “this administration raising electricity bills for more than 1 million families. Now is not the time.”

Solar for All, an initiative of the Inflation Reduction Act’s $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), had its funding frozen in January as part of a broader attack on Biden-era climate and environmental programs.

In the face of court orders declaring these freezes unlawful, in February the EPA reopened funding for Solar for All and other congressionally mandated programs. Since then, Georgia Bright hasn’t experienced any difficulty accessing its Solar for All funds, Brown said.

But because of the way that reimbursement is structured under the program, the coalition and other Solar for All awardees need the EPA to continue to make funds available to cover ongoing expenses. “It’s not like there’s $156 million in our bank account,” she said.

Other EPA-administered programs haven’t fared so well. EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin is still blocking $20 billion in funding for the broader GGRF program and is appealing federal court orders to release the money. EPA is also facing a class-action lawsuit demanding it release the billions of dollars in environmental justice block grants it terminated.

Solar for All has been something of a bright spot amid these roadblocks, Brown said. In recent months, grantees like Georgia Bright have begun rolling out their first rounds of funds.

In May, Vermont’s Department of Public Service announced $22 million in grants for low-income-housing solar projects. Last month, Michigan’s Office of Climate and Energy announced eight projects, ranging from an agrivoltaics installation near a municipal airport to solar panels on a multifamily building serving low-income seniors. And the Nevada Clean Energy Fund, a nonprofit green bank, last month announced its first project — nearly $1 million to help a sober living facility in Reno install rooftop solar.

“It seems like this program has bipartisan support — it certainly does in Nevada — because there’s a big need for it. Reducing energy costs is important, particularly in our economic environment,” said Kirsten Stasio, CEO of the Nevada Clean Energy Fund. “If an affordable housing owner needs to pay more for their utility bills, it means they are paying less on supportive services for their tenants.”

The EPA’s initial funding freeze was concerning, said Chris Walker, head of national policy and programs for Grid Alternatives, the country’s largest free solar installation nonprofit and prime contractor for more than $300 million in Solar for All grants. Still, “we were confident we were on a solid legal footing to continue the work, and continued staffing and contracting processes, with a bit of nervousness about what might be coming,” he said.

Now, as Grid Alternatives prepares to launch its first Solar for All projects, he said, “We’re in capacity-building mode and compliance mode.”

Rumors that the EPA plans to terminate Solar for All have been swirling for months, said Jillian Blanchard, vice president of climate change and environmental justice at Lawyers for Good Government, a nonprofit coalition of attorneys, law students, and activists that’s challenging other EPA funding cuts.

“There are many, many Solar for All grantees doing everything in their power to move things forward,” she said. “But EPA is not making it easy.”

Cutting off Solar for All grants would almost certainly draw a legal challenge, given that the funds were awarded by the EPA last year under contracts that cannot be terminated without cause.

“If leaders in the Trump administration move forward with this unlawful attempt to strip critical funding from communities across the United States, we will see them in court,” Kym Meyer, litigation director for the Southern Environmental Law Center, told Canary Media. “We have already seen the immense good this program has done on the ground, and we won’t let it be snatched away to score political points.”

Complicating matters, Blanchard said, is the megalaw passed by Republicans in Congress last month, which officially repealed statutory authority for the GGRF and rescinded unspent funds from the program. The law, however, does not claw back obligated funds, she said.

An EPA spokesperson declined to say if the agency intends to terminate Solar for All grants, but told Canary Media in a Tuesday email that “with the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill, EPA is working to ensure Congressional intent is fully implemented in accordance with the law.”

Blanchard said that language in the megalaw clearly indicates that the intent of lawmakers was to retain obligated spending from the GGRF. “If EPA does this unilaterally, it will be pulling a complete bait and switch on the American people, increasing utility bills, and flouting congressional intent,” she said.

Terminating Solar for All funds wouldn’t just harm the communities burdened by high and rising electricity prices, said Sachu Constantine, executive director of nonprofit advocacy group Vote Solar. It would also hurt utilities struggling to meet rising electricity demand.

A growing body of research shows that low-income neighborhoods and communities of color face greater risks of power outages and grid failures, partly due to decades of underinvestment in the grids that serve them. Solar for All “targets frontline underinvested communities, which means it’s targeting weak spots on the grid,” Constantine said. “It’s infrastructure in the right places for the right people.”

And solar and batteries are the right technology to solve the problem, he contended. Solar panels and lithium-ion batteries are not only the cheapest and fastest-to-deploy sources of new grid supply; they’re also capable of lowering peak electricity demands that drive the lion’s share of utility costs, by serving as virtual power plants.

“When we don’t have to deploy the most expensive peaker [power plants], when we can better utilize the distribution lines, we’re saving the cost for everyone,” he said. “We’re taking the entire system and making it run better.”

That’s a role Georgia Bright wants to play with its community-benefits solar program, Brown said. Last month, the Georgia Public Service Commission approved a long-term resource plan from Georgia Power, the state’s biggest utility, which has been criticized by environmental and consumer advocates for extending the life of aging coal-fired power plants and opening the door to building up to 8.5 gigawatts of new fossil gas–fired turbines.

But the plan also includes a pledge from Georgia Power to develop a pilot program that will seek up to 50 megawatts of solar and battery capacity from customers. Georgia Bright worked to get that program included in the utility’s plan, Brown said — and it plans to use its community-benefits solar program to help churches, nonprofits, businesses, and multifamily housing properties install the solar and batteries to participate in it.

“I think we’ll hit the 50 megawatts pretty quickly — and the commission is open to raise that limit,” she said. “They recognize if you need to serve all this new load, you can’t wait on natural gas plants that have a five-year backlog to get a turbine.”

Groundswell’s Southeast Rural Power Program offers similar fast-start options for utilities struggling to meet growing demand for power, Moore said. “It’s a straightforward way to work across the Southeast in very diverse states with very diverse needs.”

SECO Energy, a rural electric cooperative in Florida, is one of the potential partners for Groundswell’s new program. About 80,000 of SECO’s roughly 250,000 customers are low and moderate income, and “Solar for All checks a lot of the boxes for us to serve that segment of the population,” SECO CEO Curtis Wynn said.

“We’re in a high-growth area, and during the last two or three days, the heat index was over 100 degrees — it puts a strain on our system,” he said. “If there’s a way we can use grant dollars to buy down the cost of generation today that’s going to remain stable in the next 20 years in a rising-cost environment, that’s a huge advantage.”

After years of failing to rein in rapidly rising electricity rates, California lawmakers are hoping a radical new approach — and billions of dollars in state financing — can offer a solution.

Bills moving through the California Senate and Assembly would use money raised from state bonds to help pay for the hugely expensive process of expanding the power grid and making it less vulnerable to wildfires. This path would relieve some pressure on utility customers in California, because funding grid upgrades through bonds is cheaper than doing so through energy bills.

Utility costs have reached a boiling point in California, with customers of the state’s three biggest utilities — Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric — now paying almost twice the U.S. average for their power. Nearly one in five customers of these utilities is behind on paying their electric bills, according to a May report from state regulators.

The bills — Senate Bill 254, sponsored by Sen. Josh Becker, and Assembly Bill 825, sponsored by Assemblymember Cottie Petrie-Norris, both Democrats — aim to lower electricity costs for Californians. Both include provisions that would force the big three utilities to accept public financing for a portion of the tens of billions they plan to spend on their power grids.

The two bills have been passed by their respective legislative chambers. That’s despite opposition from the big investor-owned utilities, which object to using public funding for grid infrastructure projects because they earn guaranteed profits if they invest in infrastructure themselves. The utilities have defeated previous legislative efforts that would have crimped those future profits by having the state assume a portion of the expenses.

But the electricity cost crisis has made rate reform “a top-tier issue in California,” said Matthew Freedman, senior attorney at The Utility Reform Network (TURN), a consumer advocacy group that has joined other consumer and environmental justice groups in supporting SB 254.

“This is different from what we’ve seen in the past — and the solutions being sought by the legislature are more ambitious than what we’ve seen in recent years,” he said. TURN is hoping these dynamics will allow the public-financing portions of the bills to secure support from Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) and remain in whatever electricity-affordability legislation emerges before the end of the state legislative session in September.

TURN’s analysis indicates that pulling $15 billion out of the rate base of California’s three big utilities, as SB 254 and AB 825 propose to do, could save about $8 billion over 30 years, with $7.5 billion of that savings coming in the first 10 years. That equates to about 2–3% of an average residential customer’s bill, or about $4–$5 a month, Freedman said.

“Does this solve the affordability crisis? No. There’s no silver bullet. That’s the biggest frustration we have and that many policymakers have,” he said. But it does offer a straightforward path to a quick reduction in rates, and “we’re trying to get some near-term benefits here.”

SB 254 is an omnibus of electricity-affordability policies, ranging from streamlining permitting for grid and energy projects to forcing utilities to propose investment plans that limit their spending to the broader rate of inflation. AB 825 is more limited in scope, but the two bills share a couple of key concepts for state financing of utility infrastructure.

First, both bills would shift $15 billion in grid spending from utility capital expenditures to financing via bonds — a process known as securitization. Regulated utilities have commonly used securitization to help reduce the cost of closing aging power plants and rebuilding their grids after storms, by foregoing the return on equity that utilities typically earn for capital investments and tapping the lower cost of debt available to states or state agencies.

But there’s “little precedent for securitizing future productive utility capital spending,” Julien Dumoulin-Smith, an analyst at investment firm Jefferies, wrote in a June research note. The prospect that lawmakers might force California’s major utilities to securitize some of their highly profitable grid investments has in recent months weighed down investor expectations for the firms, he wrote.

The lawmakers pushing these bills argue that it’s more important to protect Californians from unchecked rate increases than to protect utility profits.

The state’s three big utilities are collectively planning about $90 billion in new capital expenditures from 2025 to 2028, Becker noted in a June press release after SB 254’s passage by the state Senate. Securitizing $15 billion of those investments would “reduce financing costs by eliminating profit margins and lowering interest rates,” Becker said.

In particular, the bills aim to rein in the biggest driver of rate increases — the tens of billions of dollars California’s utilities are investing in hardening their grids against the risk of sparking deadly wildfires.

“We’ve asked the investor-owned utilities to do a lot of that work, and we have to make sure it’s done as efficiently as possible,” Becker said during a virtual town-hall event in June. “I think we can have a discussion today about whether that’s something that should be in rates going forward.”

A March report from the Natural Resources Defense Council, a supporter of SB 254, examined wildfire-mitigation costs at PG&E, the state’s largest utility, which has doubled rates on average over the past decade and increased them 40% above inflation since 2018. According to that analysis, about 60% of PG&E’s rate increase stemmed from wildfire-related expenses, Merrian Borgeson, NRDC’s California policy director for climate and energy, said during the June town hall.

PG&E, which was forced into bankruptcy in 2019 after its power lines sparked the state’s deadliest wildfire, is under state mandate to invest in preventing its grid from causing more conflagrations. But the utility has also notched record-breaking profits in the midst of its record-breaking rate increases — in large part because of the guaranteed return it’s earning on that wildfire-prevention work.

Customers need quick relief from bearing those costs, and “the things that you can do the fastest to reduce electric rates are to take things out of rates,” Borgeson said.

Freedman of TURN highlighted differences between the securitization approaches of SB 254 and AB 825. AB 825 would apply only to the costs of burying power lines to prevent them from sparking wildfires. These “undergrounding” projects make up a big chunk of the broader wildfire-mitigation spending, particularly for PG&E. SB 254, by contrast, would apply to wildfire mitigation more broadly, as well as to spending to expand utility grids to serve fast-growing demand for electricity from big new loads like data centers and electric-vehicle charging hubs.

But in both cases, replacing utility spending with state borrowing would significantly lower costs to utility customers, he said. First, California can borrow money at lower rates of interest than utilities can. Second, the state can spread out the costs over a longer period of time, and reduce the portion of costs borne in earlier years, compared to how utilities pass on the cost of capital investments to their customers, he said.

It’s also been done before in California. In 2019, lawmakers passed a $21 billion wildfire bill to backstop California utilities’ financial stability in the face of PG&E’s bankruptcy. That bill forbade utilities from recovering a return on $5 billion in investments in wildfire-mitigation spending, but offered them the option of securitizing that spending instead, which they accepted. That’s expected to reduce ratepayer costs by as much as $2 billion over the lifetime of those assets.

The $15 billion securitization plan in SB 254 and AB 825 is targeted at reducing utility costs and rates in the shorter term. But both bills also propose a longer-term public-financing option aimed at the state’s high-voltage transmission grid.

“The idea here is to establish a state infrastructure authority that would have the capacity to finance and own these lines,” Freedman said.

That’s not a completely novel concept. The state-run New York Power Authority has owned and managed transmission grids since the 1930s, as have federal power-marketing entities such as the Bonneville Power Administration and the Tennessee Valley Authority. More recently, New Mexico and Colorado have created transmission authorities to facilitate grid buildouts.

The California Independent System Operator, which manages the state’s grid, estimates that California must spend between $46 billion and $63 billion over the next 20 years to meet its goal of achieving a carbon-free grid by 2045. An October report from Net-Zero California and Clean Air Task Force found that “traditional investor-owned utility financing and development” of those projects “could substantially increase consumer rates,” but that a public-private partnership model could reduce those costs by up to 57%, saving utility customers as much as $3 billion per year compared to a status-quo approach.

“There are lots of institutional changes, and changes to authorities that operate in California, needed to operationalize the full range of those savings,” said Nicole Pavia, Clean Air Task Force’s director of clean energy infrastructure deployment. SB 254 and AB 825 don’t specify what form any future public-private ownership or public-financing structures for transmission might take, she noted. But both “are picking up pieces of the institutional changes that might be needed to advance some of these savings.”

The two bills take different approaches to this issue, Freedman said. SB 254 would establish a new Clean Infrastructure Authority to take on the work, while AB 825 would revitalize the California Consumer Power and Conservation Financing Authority, a now-defunct entity created after the state’s 2001 energy crisis to finance new power generation, he said.

The move to increase state authority over transmission development would not offer immediate relief to ratepayers, said Vivian Yang, an analyst at the nonprofit Union of Concerned Scientists.

“These are big projects that are regardless going to take five to 10 years,” she said. “It’s not like we can pass those public-financing bills and then the next year our rates will go down.”

Instead, it would help the state position itself to avoid yet another cost crisis in the years to come. Given the massive amount of transmission California will need over the coming decades, “having all these tools to get us there — one of which is public financing for projects — is really important,” she said. California needs to get to work now to “have these structures up and running already and use them more nimbly, and not discover 10 years out that we’re stuck using what we’ve got.”

The Trump administration has officially announced it is killing the $7 billion Solar for All program. The program had awarded grants to 60 state agencies, municipalities, tribal governments, and nonprofits across the country to help low-income households access solar power. Supporters of Solar for All are vowing to fight the move in court.

On Thursday, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin posted a video on the X social media platform stating that he was terminating the program. Solar for All was created as part of the Inflation Reduction Act’s $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), which has also been under attack by the Trump administration.

Zeldin stated that the mega-law passed by Republicans in Congress last month “eliminates billions of green slush-fund dollars by repealing the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund.”

Referring specifically to Solar for All, Zeldin said, “EPA no longer has the authority to administer the program, or the appropriated funds to keep this boondoggle alive. With clear language and intent from Congress in the One Big Beautiful Bill, EPA is taking action to end this program for good.”

Defenders of Solar for All challenge Zeldin’s interpretation of the One Big Beautiful Bill, or HR 1, and the intent of its provisions.

“It is absolutely ludicrous to suggest that HR 1 rescinded these funds, because they were all under legally obligated grant awards when the bill was signed,” said Jillian Blanchard, vice president of climate change and environmental justice at Lawyers for Good Government, a nonprofit coalition of attorneys, law students, and activists that’s challenging other EPA funding cuts. “HR 1 only rescinded unobligated grant funds,” she told Canary Media on Thursday.

That’s an important distinction, she said. Those unobligated grant funds amounted to only $19 million, as determined by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) when it conducted its analysis of the pending legislation’s overall financial impact. The vast majority of the funds, the office found, were already committed under legally binding contracts to the parties awarded grants during the Biden administration.

But in a court case challenging the EPA’s effort to claw back $20 billion in funds for other GGRF programs, administration officials have claimed that HR 1 terminates the government’s obligation to meet any of its contractual obligations.

Attorneys for nonprofit groups fighting EPA’s attempt to claw back their grants argued that the law clearly states that only “unobligated balances of amounts made available to carry out that section … are rescinded.”

The attorneys also noted that Sen. Shelley Moore Capito, the West Virginia Republican and chair of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, stated during a congressional debate before the bill passed that funding “that’s already been obligated and out the door, that’s a decision that’s final,” and that arguing the law would claw back obligated funding is “a ridiculous thought.”

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) pointed out this same discrepancy in a July press release attacking EPA’s characterization of the law. “Trump’s DOJ is continuing its mischief by falsely claiming Republicans’ Big Beautiful-for-Billionaires Bill claws back $17 billion from GGRF, even though the CBO score for the unobligated funds was $19 million — what was left to oversee the program after the grant funds had been obligated — and Republicans made clear that their rescissions only touched unobligated funding,” Whitehouse wrote.

The Solar for All program is meant to deliver energy-bill savings of $350 million over the next five years to 900,000 low-income and disadvantaged households and deploy 4 gigawatts of solar generation capacity. In the past few months, a handful of grantees had begun issuing awards to low-income housing projects, municipal facilities, nonprofits, and low-income homeowners.

“Communities promised relief from punishing energy costs are now left in the dark,” Zealan Hoover, a former EPA senior advisor under the Biden administration, told Canary Media. “Nearly a million families will pay hundreds of dollars more each year for their electricity bill because the Trump administration killed a program that would have more than paid for itself.”

Michelle Moore, CEO of Groundswell, a Washington D.C.-based nonprofit that is administering a $156 million Solar for All grant aimed at developing large-scale solar and battery projects in Southeastern states, said that ending the program would run counter to President Donald Trump’s pledge to lower energy prices.

“I would hope [the Office of Management and Budget] could find the funding to cover EPA staff time to help keep President Trump’s campaign promise to cut bills in half and keep energy affordable for American families, which this program does,” she told Canary Media.

President Donald Trump’s new budget law repeals a key federal tax incentive for residential solar — and rooftop solar installations are about to plunge as a result.

Americans are expected to install 33% less rooftop solar next year than they would if federal incentives were still in place, per an updated analysis from Ohm Analytics. That’s a better outcome than the research firm’s earlier, gloomier forecast, which was based on a version of the law that would have also scrapped a separate tax credit that applies to leased systems.

The repeal of the 25D tax credit, which knocks 30% off the price of home solar and storage, will make the technology significantly more expensive. The incentive was originally available until 2035 but now disappears at the end of this year.

Already, residential solar is far more expensive in the U.S. than elsewhere, and high interest rates as well as recent state-level policy developments are eating further into the economics of buying panels. Even before the repeal, rooftop solar installations were declining year over year because of these trends.

In 2025, though homeowners are expected to fast-track solar purchases before the tax credit expires, Ohm expects an 8% decline in installations compared with last year. In 2026, the total gigawatts installed will shrink by 26%, it forecasts.

Rooftop solar is an important piece of the energy transition. In California, photovoltaic panels on roofs produce almost as much power as the sprawling large-scale arrays found in fields and desert areas.

But it’s also a critical way for people to hedge against utility rates, which have climbed high in recent years and are expected to rise even further as data centers demand more energy and the Trump administration stymies cheap wind and solar power. Most households that install rooftop solar see their energy bills drop. Poorer households benefit most.

Still, there are things within the industry’s control, from reining in “soft costs” to developing more virtual power plants, that can help it weather the storm — and make rooftop solar more affordable to Americans even without long-standing tax credits in place.

CALISTOGA, Calif. — A quaint northerly outpost of Napa Valley wine country, Calistoga has struggled to keep the lights on when wildfires strike the region. Now it’s got a brand-new microgrid to run the whole town for days on end without any onsite fossil fuels, just batteries and liquid hydrogen.

After disastrous conflagrations in 2017 and 2018, utility Pacific Gas & Electric began preemptively shutting off power lines to avoid sparking fires amid dangerously dry, windy conditions.

“We were the first community in all of PG&E’s network that was getting our power shut off to protect us,” said Calistoga City Council member Lisa Gift. “By 2019 we were one of the first communities to have a microgrid in all of PG&E’s network, and that was being powered by diesel generators.”

PG&E arranged a bank of truck-based diesel generators to sit in the town during fire season. When the utility cut grid power, the generators kicked on, belching smoke in a particularly beloved pocket of the 5,000-person community.

“We’re a small town, so they would come up and they’d be polluting the environment, taking up our dog park — loud, gross, noisy,” Gift recalled.

Now the diesel generators are gone and the park has been turned back over to Calistoga’s canine companions.

On a slim parcel of city land next door, publicly traded energy-storage company Energy Vault installed lithium-ion batteries and a 234-foot, reinforced-steel tank for liquid hydrogen (designed to withstand a roaring fire, should it ever come to that) that runs a bank of hydrogen fuel cells. Altogether, this compound should be able to meet Calistoga’s electricity needs without any power from the broader grid. It’s contracted to produce up to 8.5 megawatts for 48 hours, whenever PG&E shuts off grid power due to fire concerns. Refilling the hydrogen tank could let it run for several days more.

“Even though we’re taking elements — fuel cells, batteries, liquid hydrogen storage and distribution — that have been used before in commercial settings, they’re coming together for the first time as resiliency,” said Craig Horne, Energy Vault’s senior vice president for advanced energy solutions, in an interview before the project’s unveiling in early August.

Fans of hydrogen hail it as a solution to just about any entrenched decarbonization challenge, from heavy transport to steelmaking to on-demand power. But how hydrogen is produced makes a huge difference in its climate impact; seemingly clean sources can actually rack up major carbon emissions for negligible benefit. For now, the clean hydrogen economy remains largely speculative, with hardly any truly clean hydrogen being produced or any real projects using it. Many planned clean hydrogen projects have vanished without a trace, following a short-lived boom fueled by Biden-era support.

In Calistoga, Energy Vault has tapped hydrogen to deal with a very specific set of constraints — delivering energy without local emissions, over multiple days, in a tight footprint — but the cleanliness of that hydrogen is a more complicated issue than public descriptions of the microgrid suggest.

The key players all have a lot riding on the project.

Energy Vault, which previously raised several hundred million dollars in a singular bid to store energy with multi-story robotic cranes that stack blocks, wants to build a new long-duration storage business around this hydrogen microgrid showcase. Plug Power, the financially challenged hydrogen company, points to Calistoga as its largest deployment of hydrogen fuel cells (a beefy 8 megawatts, after 28 years of hard work). And PG&E has orders from regulators to add more clean energy microgrids in communities where it regularly cuts off power — Calistoga was its first delivery on that directive, after a few years of soliciting proposals and a couple more years of permitting and construction.

“Community microgrids are the future of the energy system,” said Craig Lewis, who advocates for such projects as executive director of the Clean Coalition nonprofit. The Calistoga microgrid is “a commercial-scale experiment, and I’m grateful for it.”

The results of that experiment will take time to analyze. It could unleash a new, replicable model for premium-priced community-level backup power. Or the quirkiness of the design and the murkiness of hydrogen’s supply chain and emissions could make it a quixotic outlier of questionable climate value.

The Calistoga microgrid poses an answer to the question of how to provide a few days of backup power to a small town in a small space, without worrying too much about cost. The limitations drove the design, which turned out quite unlike anything built thus far.

Energy Vault had to figure out how to pack 293 megawatt-hours of storage into just two-thirds of an acre. The lot used to hold debris from city works, like old bits of sidewalk and pipes, Horne said.

Lithium-ion batteries have proven themselves capable of storing power, be it as a Powerwall in someone’s garage or as a large-scale grid storage facility. But to store nearly 300 megawatt-hours, grid battery enclosures need more acreage than was available to lease from the city. Even if enough batteries could fit, the auxiliary power consumption for keeping them safely cooled would pose a challenge for a project that’s supposed to mostly sit around waiting for an emergency event.

Hydrogen gas can be liquefied by cooling it to ultra-low temperatures, which unlocks greater energy density. When converted back to gas and run through fuel cells, it produces a stream of electricity and no byproduct besides water vapor. That core technology powers hydrogen vehicles, though their cost and inconvenience make for a widely derided car-ownership experience. At Calistoga, the hydrogen flows directly to six Plug Power GenSure 1540 fuel cells, boxy containers with cooling units stacked on top, making them about two stories tall.

The engineers added a small lithium-ion battery (7.7 MW/11.6 MWh) to perform “black start,” the complicated and crucial task of rebooting an electrical system after a complete blackout, Horne noted. The battery also buffers the output of the system while the hydrogen gets up and running. Then the power flows to Calistoga’s grid, which, when PG&E shuts off the transmission lines, will be fully islanded from the surrounding network.

The hydrogen is stored onsite in an 80,000-gallon tank, manufactured in Minnesota by Chart Industries. The tank holds enough to power the fuel cells for about two days, but Energy Vault will try its best to keep the lights on beyond the contracted timeframe, Horne said. So the company made sure the tank can be refueled while it’s in active use.

“The task is to squeeze toothpaste into a toothpaste tube that was being squeezed,” Horne said. “That’s what we proved in our acceptance testing, running for multiple hours while the fuel cells were running and a tank trailer here in the driveway is pushing liquid hydrogen into the tank itself.”

The microgrid’s promise as a clean energy breakthrough, of course, hinges on the supply of clean hydrogen, but supply chains are barely getting started. Almost all commercial hydrogen is currently made from methane gas, a fossil fuel, through a procedure called steam methane reforming that sends the carbon dioxide byproduct straight into the atmosphere.

For hydrogen to stake any claim as a climate solution, it needs to be made without massive carbon emissions. That usually involves an alternative production method called electrolysis, which separates hydrogen from water using electricity. But this method can produce even more emissions than the dirty methane version if the electrolyzers are drawing power from the grid rather than dedicated renewable sources like solar and wind (see this previous Canary Media coverage for a detailed account of why that’s the case).

Energy Vault describes the hydrogen it’s using in Calistoga as “clean,” which Horne clarified as meeting the federal standard of no more than four kilograms of carbon dioxide emitted per kilogram of hydrogen produced. But he declined to name the source. Notably, California has subsidized hydrogen fueling stations for over a decade but still hasn’t managed to develop a clean hydrogen supply in-state. So for Calistoga’s hydrogen to be clean, it must be coming from somewhere else.

During a tour of the microgrid, Deepesh Goyal, vice president of stationary power at Plug Power, told Canary Media that Plug Power currently supplies hydrogen from its electrolyzer site in Georgia, which runs on grid power. More than half of Georgia’s electricity comes from fossil fuels, so that electrolysis incurs substantial power-plant emissions. Plug Power buys credits for clean energy supply to compensate for this, Goyal said.

To meet the highest federal standard for clean hydrogen, producers need to obtain clean power matched to their consumption on an hourly basis in the areas where they operate. Plug Power did not respond in time for publication to questions clarifying what type of credits it buys. But a spokesperson for Energy Vault told Canary Media that currently there aren’t any facilities that could supply Calistoga with liquid hydrogen from electrolysis powered by time-matched, dedicated clean electricity, and the earliest such facility is targeting completion in 2026.

Goyal also said some of Calistoga’s hydrogen comes from an unnamed partner in Las Vegas that uses renewable natural gas (RNG) as its feedstock. As it happens, legacy gas supplier Air Liquide opened a steam methane reformer in that area a few years ago to serve California’s demand. Air Liquide says it can substitute RNG for the usual methane, which would make the resulting hydrogen carbon-negative according to the convoluted calculations of California’s clean fuels bureaucracy. It’s still hydrogen made by splitting methane and releasing carbon dioxide, but it looks good on paper thanks to controversial rules that privilege certain politically connected providers of RNG.

If someone were to design a climate solution from a blank slate, they probably wouldn’t run electrolyzers on grid power in Georgia in order to load the super-cooled hydrogen onto diesel-powered tankers and haul it more than 2,800 miles to Northern California, where it will sit around almost every day awaiting a utility power outage.

“We still have to truck in that hydrogen,” said Gift. “That’s not ideal, but we were trucking in the diesel, and we were trucking in the diesel sometimes three times a day and burning that diesel.”

One incontrovertible fact is that the microgrid doesn’t combust anything onsite, so the operations within the fenceline emit almost no carbon emissions and don’t impact air quality. But it will be hard to gauge the real climate impacts of such a project until a more verifiably clean and geographically localized hydrogen supply chain develops. Several companies have said they will build truly green hydrogen production in the coming years. That task has only grown more difficult with the Trump administration’s efforts to thwart renewables development and vastly curtail clean hydrogen tax credits.

The other make-or-break variable for hydrogen-backed resilience is how much it costs. Liquid hydrogen is an expensive, specialty fuel only produced by a handful of suppliers in the U.S., and clean liquid hydrogen is even rarer.

For this first project, Energy Vault didn’t need to worry about consumer price sensitivity. The city of Calistoga isn’t paying Energy Vault for backup power: PG&E is paying the company to provide this service, out of funds socialized across the utility customer base. In fact, Calistoga is making some money, since Energy Vault leased the land from the municipality for 10 years.

The project’s total price tag has not been made public. Regulators allocated up to $46.3 million for PG&E to spend on the endeavor. Energy Vault closed $28 million in project financing this spring to support construction. (The company also said on Thursday that it has raised $300 million to launch Asset Vault, a subsidiary that will build, own, and operate storage projects, with Calistoga as one of two anchor properties.) Horne allowed that the hydrogen microgrid costs more than diesel generators up front, but argued it can be competitive in terms of operating costs, given all the hassles associated with diesel.

“We can do more and waste less, and so that’s how we can be more cost effective,” he said.

The regulatory authorization paints a different picture. The California Public Utilities Commission explicitly allowed PG&E to spend more money than the diesel generators cost in order to test a new model for cleaner resilience.

“This project was supported by a CPUC plan that said we could build a solution that costs no more than twice what it would cost to deploy diesel generation over 10 years,” said Jeremy Donnell, a senior manager for microgrid strategy and implementation at PG&E. “It’s a bit of an arbitrary marker, but that’s what was laid out, and this project did come in under that threshold.”

“But still, we have a ways to go to bring the cost down,” Donnell added. “So hopefully, through implementation of this first project, Energy Vault learned a lot, the industry learned a lot on how to integrate these solutions in future projects.”

Energy Vault hopes to improve the project economics by upgrading the site to allow regular power exports to the grid. Currently, the system is configured to only push out power when PG&E has scheduled a shutoff event; that means the microgrid sits idle almost every day of the year (and is unavailable for unforeseen outages, like if a tree falls on a key line). But with the right permissions and technical tweaks in place, Energy Vault expects to use the battery, and potentially even the hydrogen, to send power to California’s grid at particularly lucrative times.

“We can now have a viable second revenue stream outside of providing that resiliency service, without compromising our ability to provide the resiliency service,” Horne said. PG&E amended its contract this summer to clarify that Energy Vault is allowed to pursue this, provided it does not interrupt delivery of the required resilience services.

Going forward, Calistoga will serve as a showcase for Energy Vault’s new “H-Vault” product line, marketed as a high-tech option for long-duration clean energy needs. Hydrogen tanks will join gravity-based block stacking and conventional lithium-ion batteries as the company’s core offerings.

For the people of Calistoga, the project softens the upheavals of living through climate change–induced extreme weather, without all the downsides of onsite fossil fuel combustion.

“Is it absolutely perfect? No,” Gift said. “But as a society, it is about making that next best right step. And for us in our community, this was that next best right step.”

For Energy Vault and the budding hydrogen industry, the next right step will be expanding hydrogen production that’s definitively low-emissions, and closing the 2,800-mile gap between supply and demand.

Wendy Becktold contributed reporting from Calistoga.

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the week” column.

Just under three years ago, the Inflation Reduction Act went into law and generated tens of billions of dollars’ worth of investment in domestic manufacturing of clean energy technologies. President Donald Trump has turned that wave into a ripple.

Since Trump took office in late January, companies have paused, canceled, or shuttered 26 different manufacturing projects that would have brought $27.6 billion in investment and nearly 19,000 jobs to communities across America, according to new data from The Big Green Machine, a project from Wellesley College.

Over that same time period, 29 new projects were announced for a total of just $3 billion.

Under the Biden administration, companies pledged well over $100 billion in factory investment, thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act’s incentives for manufacturers and for project developers and people to buy American-made solar panels, batteries, electric vehicles, and more. The cleantech manufacturing surge was so significant that it pushed overall manufacturing construction to heights not seen in decades.

Areas represented by Republicans in Congress stand to gain the most from this factory boom. More than 80% of the clean-energy manufacturing investment announced as of February would flow to Republican-led districts; over 70% of the jobs would go to these places.

But under Trump’s new “big, beautiful” law, the future of those projects is less certain.

The law did not repeal tax credits for most clean-energy manufacturers, but it will eat away at their customer base by scrapping subsidies for wind and solar developers. It also introduced strict anti-China stipulations to the manufacturing tax credit, which could be a headache for companies to comply with, depending on how the Treasury Department decides to enforce the rules.

These factors, in addition to the increasingly volatile business environment in the U.S., do not bode well for the clean-energy manufacturing boom regaining momentum in the near term. Nor do Trump’s beloved tariffs hold much promise as a way forward. Previous attempts to boost domestic solar-panel manufacturing via tariffs alone have failed, and experts say Trump’s measures will actually drive costs up for U.S.-based producers.

That’s not to say cleantech manufacturing is now a lost cause in the U.S. — some solar producers, for example, are feeling optimistic. But what’s increasingly clear is that the short-lived boom times are over, and any manufacturing success stories from this point on will be in spite of the federal government rather than because of its generous support.

Offshore wind leasing is effectively dead in the U.S. following a Trump administration order issued this week.

Large swaths of U.S. waters that had been identified by federal agencies as ideal for offshore wind are no longer eligible for such developments under an Interior Department statement released Wednesday.

In the four-sentence statement, Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) said the U.S. government is “de-designating over 3.5 million acres of unleased federal waters previously targeted for offshore wind development across the Gulf of America, Gulf of Maine, the New York Bight, California, Oregon, and the Central Atlantic.”

The move comes just a day after Interior Secretary Doug Burgum ordered his staff to stop “preferential treatment for wind projects” and falsely called wind energy “unreliable.” Analysts say that offshore wind power can be a reliable form of carbon-free energy, especially in New England, where the region’s grid operator has called it critical to grid stability. It also follows the Trump administration’s monthslong assault on the industry, which has included multiple attacks on in-progress projects.

The outlook was already grim for new offshore wind leasing activity following President Donald Trump’s executive order in January that introduced a temporary ban on the practice. Wednesday’s announcement makes that policy more definitive. Wind power advocates say it will erase several years of work from federal agencies and local communities to determine the best possible areas for wind development.

“My read on this is that there is not going to be any leasing for offshore wind in the near future,” said a career employee at the Interior Department, who Canary Media granted anonymity so they could speak freely without fear of retribution.

Figuring out the best spot to place offshore wind is an involved undertaking. The proposed areas start off enormous and, according to the Interior staffer, undergo a careful, multiyear winnowing process to settle on the official “wind energy area.” Smaller lease areas are later carved out of these broader expanses.

Take the process for designating the wind energy area known as “Central Atlantic 2,” which started back in 2023 and is now dead in the water.

The draft area — or “call area” — started out as a thick belt roughly 40 miles wide and reached from the southernmost tip of New Jersey to the northern border of South Carolina, according to maps on BOEM’s website. Multiple agencies, including the Department of Commerce, the Department of Defense, and NASA, then provided input on where that initial area might have been problematic. NASA, for example, maintains a launch site on Virginia’s Wallops Island and in 2024 found that nearby wind turbines could interfere with the agency’s instrumentation and radio frequencies.

The winnowing didn’t stop there. By 2024, according to BOEM’s website, its staff was hosting in-person public meetings from Atlantic City, New Jersey, to Morehead City, North Carolina, to gather input from fishermen, tourism outfitters, and other stakeholders. Under a wind-friendly administration, a final designation and lease sale notice would have likely been released this year or by 2026, based on a timeline posted to BOEM’s website.

But the Trump administration is no friend to offshore wind.

Trump officials have repeatedly targeted wind projects by pulling permits and even halting one wind farm during construction. Last month, Trump’s “big, beautiful bill” sent federal tax credits to an early grave, requiring wind developers who want to use the incentives to either start construction by July 2026 or place turbines in service by the end of 2027. The move is particularly devastating for offshore projects not already underway. Currently, five major offshore wind farms are under construction in the U.S., and when they come online, they will help states from Virginia to Massachusetts meet their rising energy demand with carbon-free power.

Wednesday’s order halts all work on Central Atlantic 2 and similar areas, like one near Guam, and also revokes completely finalized wind energy areas with strong state support. One example is in the Gulf of Maine, where Gov. Janet Mills, a Democrat, has been a fierce advocate for the emerging renewable sector.

These wind energy areas could hypothetically be re-designated by a future administration or the policy reversed, according to the Interior Department employee. Still, in the best case, that means developers will have to wait several more years for new lease areas to become available, further slowing down an industry whose projects already take many years to go through permitting and construction.