SOLAR: The U.S. Energy Department plans a 1,000 MW solar installation on about 8,000 acres of the Hanford nuclear weapons production site in south-central Washington. (Canary Media)

ALSO:

CLEAN ENERGY: Data show the California grid met 100% of its electricity demand with renewable energy during 5- to 10-minute periods on 100 of the last 144 days. (news release)

ELECTRIC VEHICLES: A southern California city becomes the nation’s first to replace its entire fleet of gasoline-powered police patrol cars with electric vehicles. (Associated Press)

ELECTRIFICATION: The U.S. EPA awards Alaska organizations nearly $39 million to replace households’ fossil fuel based heating systems with electric heat pumps. (KTOO)

BATTERIES: A developer and a Colorado electric cooperative bring a 78.3 MW battery energy storage system online. (news release)

CLIMATE:

UTILITIES: Tucson, Arizona’s city council considers establishing a municipal utility as part of its goal to achieve community-wide carbon-neutrality by 2045. (Cronkite News)

HYDROPOWER: A firm deploys a 1.25 MW wave-energy generator at a U.S. Navy testing site off Hawaii’s coast. (Marine Technology)

HYDROGEN: California environmental justice advocates worry a public-private effort to establish a hydrogen production and distribution hub in the state could increase pollution if strict guidelines aren’t followed. (Grist)

OIL & GAS: Oregon advocates continue to protest a natural gas pipeline expansion even though developers began construction earlier this month. (KTVZ)

COAL: Wyoming officials predict a 25% dip in coal production from the Powder River Basin and weak natural gas prices could diminish mineral tax revenues and strain the state budget. (Cowboy State Daily)

Research underway at a Madison County solar farm promises to shed light on how well multi-use farming can work at a large scale. The answers will help shape best practices for future projects, while addressing some concerns raised in ongoing debates over siting large solar projects in rural farm areas.

Spread across more than 1,900 acres, the 180 MW Madison Fields project will be one of North America’s largest test grounds for research into agrivoltaics — essentially farming between the rows on photovoltaic solar projects.

As farmers seek to lease land for solar arrays to diversify their incomes, the practice could help them maximize their income and fend off opposition from critics concerned that solar development will take prime farmland out of production.

Some farmers have also said the revenue from clean energy can help keep their farms operating amid pressure from housing developers. A recent report from the American Farmland Trust says Ohio could lose more than 518,000 acres of farmland to urban sprawl by 2040.

That number dwarfs the roughly 95,000 acres for certified and other projects noted on the Ohio Power Siting Board’s most recent solar case status map.

Yet solar projects generally deal with big chunks of land at once, while urban sprawl happens bit by bit over time, said Dale Arnold, director of energy policy for the Ohio Farm Bureau. Helping people understand and appreciate that is “absolutely huge,” he said.

Savion, a Shell subsidiary, developed the Madison County project, and it began commercial operation on July 11 with Amazon as the long-term buyer for its energy. Yet work began much earlier this year to set up the site for research by Ohio State University scientists, Savion’s Between the Rows subsidiary, and others.

“People have a lot of questions with regard to energy development going forward in this state,” particularly when it comes to taking land out of use for agricultural production, Arnold said.

Yet today’s industry continues to shift away from coal to a diversified portfolio of natural gas, nuclear, hydropower, wind energy, solar energy and other types of generation. Forecasts also show there will be growing demand for electricity by mid-century, he said.

“Finding a balance where you can do a number of things on the same ground — in this case energy production as well as agricultural production — is obviously huge,” Arnold said. If agrivoltaics is to become more than a buzzword, though, both farmers and solar project developers need to work out best practices.

One big issue is what crops can work well for large-scale utility projects. Compared to most solar farms projects in Eastern and Piedmont states, utility-scale solar projects in Ohio and other Midwestern states can spread across 1,000 acres or more, Arnold said.

“You hear a lot about produce and specialty crops,” for example, said Sarah Moser, Savion’s director of farm operations and agrivoltaics. But raising them is “hard to do on 1,000 acres.”

Moser and Ohio State University researchers think forage crops like alfalfa and hay hold promise. Operations can be scaled up for large areas, said Eric Romich, an Ohio State University Extension field specialist for energy development. And the crops wouldn’t grow too tall amid the panels.

“We also wanted something that we felt had the potential to be economical,” Romich said.

Two 2023 reports by Ohio State University Extension researchers found raising hay and alfalfa between rows of solar panels was feasible and that the harvest’s nutritive value was good. But that small-scale work at the Pigtail Farms site in Van Wert County used data from only a few test plots and controls, which is an important limitation, Romich said.

Work at Madison Fields will now test whether similar results can be achieved at large scale. Part of a $1.6 million grant from the Department of Energy will help pay for that work over the course of four years.

Other research will test how well plants do in sun versus shade, Romich said. That matters because some portion of the land among solar panels will always be shaded.

Researchers planted the crops on test fields and control areas this spring, with an eye toward starting to collect data next year. “Forages are quite temperamental in terms of trying to get them established,” said Braden Campbell, an animal scientist at Ohio State University who is also working on the project. The team has found compacted soil around the solar panels, “but we are relieved to see that the seeds that we put into the ground are growing,” he said.

Moser plans to work with other crops, too. Soybeans are one example. They were already used as a cover crop before alfalfa and hay were planted. Soybeans can also work into a crop rotation when forage crops need to be replanted every few years.

“The market is there for it, and it does well” as a hardy crop which can also loosen soil and restore nutrients to it, Moser said, adding that local communities have expressed interest in the crop as well.

Other work at Madison Fields will explore complementary grazing. The goal is to harvest the forage crops as efficiently as possible. But there will still be a need for vegetation control under and around panels and other infrastructure, said Campbell. So, after harvesting, sheep will go to work.

“To me, that’s three commodities that we can get off one unit of land,” Campbell said: Solar panels will produce electricity. Hay and alfalfa growing will provide a crop. And the land will help support sheep, which in turn can produce meat, milk and fiber.

Other solar farms already use or plan to use sheep for vegetation control. But “there is a big difference” between using sheep to keep plants under control and relying on that for their nutrition, Campbell said.

Studies will need to test the health of sheep that do complementary grazing, compared to other sheep. Other questions include finding optimal grazing rates of sheep per acre, as well as other logistics. But first, the forage needs to establish good roots so it can withstand the pressure of grazing.

A third bucket of research questions under the Department of Energy grant will focus on farm equipment. Tractors and other farm vehicles need to fit between the rows with their attachments. There’s been a trend in the agricultural sector toward wider equipment, which can cover more ground quickly but may not fit between rows of solar panels, Moser said.

“But a lot of farmers still have smaller equipment,” Moser continued, because some parcels aren’t appropriate for wider machinery. Maneuvering 15-foot-wide equipment works fairly well, and 17-foot and even 20-foot widths can still work.

“I could get my 20-foot drill in there,” Moser said. “I just have to be careful.”

Arnold speculated that some companies may develop special equipment whose attachments can fit under solar panel rows more easily. Other possibilities could include raising panels or even feathering them when agricultural equipment is in use, he suggested.

Farm equipment doesn’t just need to go down an alley between two rows of solar panels. It will also have to turn around at the end to go down another one, Arnold said. So, there needs to be an adequate turning radius, without cables blocking farm vehicles’ paths. Poles, stands, and other equipment also can’t block the path of the farm equipment, he said.

The research can help guide the design of future solar projects to be “hay-ready” sites, Romich suggested. At the same time, agricultural operations shouldn’t jeopardize the safe and efficient operation of a solar facility. “It’s an operating power plant,” Romich said.

Arnold has additional questions about infrastructure needs: What facilities will be necessary to dry, bale and store forage? What facilities will other crops need? And how will they be trucked out to markets?

Likewise, what equipment and facilities will be needed for any sheep kept on site? That includes paddock fencing, water, and so forth. And where will their caretaker live?

“You’re going to have to have people there full-time,” Arnold said.

The Ohio State researchers, Moser, and others also wonder how well precision agriculture can work with solar farms. The term refers to methods that rely on technology and data to guide farmers’ work. The range of technologies includes remote sensing of field conditions with drones, in-ground sensors, automated weeders and more.

The big question is which precision agriculture technologies can work well for crops planted between rows of solar panels as they generate electricity.

It’s unclear what any of the studies will show until data has been collected and analyzed, Romich said. By the end, he feels the work will provide a better understanding of what will or won’t work.

Economics questions about business models, contractual arrangements and more also must eventually be worked out, Arnold said. At the end of the day, farmers will need to make a profit if agriculture is to successfully blend with solar projects.

“The possibilities are limitless, really,” when it comes to business arrangements, Moser said. “My motto is always, ‘farmers figure it out.’ And if we work with them, we’ll figure…out how to do this with best practices.”

All over the country, small and niche farming operations have proved solar panels and agriculture can not only work well together, but can actually be mutually beneficial.

In Maine, low-growing blueberries have had some success being planted around panels. In Vermont, fussy saffron thrives around an array. And there are plenty of farms where sheep and other small livestock graze around solar panels, enjoying the shade while keeping vegetation under control.

Now, an Ohio research project aims to find out how farming/solar partnerships — also known as agrivoltaics — can succeed on a much bigger scale, the Energy News Network reports.

At the 1,900-acre Madison Fields project, Ohio State University researchers planted popular crops grown in huge numbers across the Midwest — mainly alfalfa, hay, and other forage crops — among an 180 MW solar array. Researchers found these crops grew well among solar panels in an earlier, smaller pilot, but it’s unclear how feasible it is to grow them on a large scale.

“You hear a lot about produce and specialty crops,” explained Sarah Moser, the director of farm operations and agrivoltaics at Shell subsidiary Savion, which built the solar array. But raising them is “hard to do on 1,000 acres.”

Another part of the project focuses on farm equipment, including whether tractors and other wide equipment can fit between rows of solar panels. And after crops are harvested, the farm will bring in sheep to help trim back any extra vegetation. Researchers will keep an eye on the sheep’s health, and take note of what other care they’d need to live among solar panels.

It’s all in an attempt to alleviate fears in Ohio and beyond that solar farms are using up valuable agricultural land — though as one agricultural conservation group has found, urban sprawl is a much bigger threat.

Read more about the Madison Fields project at the Energy News Network.

💧 Hydrogen debate continues: As the federal government starts sending funding to seven hydrogen hubs, researchers and advocates warn the industry could worsen greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution if it uses non-renewable power to make the fuel. (Grist/Public Health Watch)

☎️ Unexpected IRA lifeline: Former President Trump promises to halt Inflation Reduction Act spending if he’s elected, but legal and practical challenges, as well as Republican governors and lawmakers benefitting from the law, could hinder his efforts. (Politico)

🛢️ ‘Sacrifice zone’: A surge in oil and gas production, largely driven by fracking, has turned the U.S. into the world’s top producer — and fuels concern that the Gulf Coast is becoming a “sacrifice zone for the oil and gas industry.” (The Guardian)

💲 Tax credit firsts: A set of projects across Washington, D.C., and California mark the first time a company sold its Inflation Reduction Act solar tax credits to another company, a key tool to help encourage solar in new construction. (Canary Media)

💸 Paying for nothing: A condition of free trade agreements often lets fossil fuel companies pursue and secure big payouts if governments cancel their projects. (Inside Climate News)

🏛️ Federal proving ground: The U.S. General Services Administration, which runs the nation’s federal buildings, is using Inflation Reduction Act funding to decarbonize its infrastructure and derisk new technologies that can help other buildings cut their emissions. (Canary Media)

⚖️ Emissions rule fight continues: Republican state attorneys general ask the Supreme Court to temporarily block the U.S. EPA’s power plant emissions rule after a federal appeals court declined to do so. (CNN)

✅ Duality of the deal: Climate advocates hope Vice President Kamala Harris rekindles her support for the Green New Deal as she runs for president — as do Republicans, who hope to paint Harris as an “avowed radical.” (New York Times)

🔋 Batteries’ recycling edge: Researchers argue that the recyclability of electric vehicle battery minerals give them an environmental advantage over fossil fuels, despite the massive impact of mining for lithium and other components. (Canary Media)

🌬️ Winds of change: Wind development continues to divide residents in Midwest states, as misinformation leads to restrictive local regulations and local economic benefits can take years to materialize. (Associated Press)

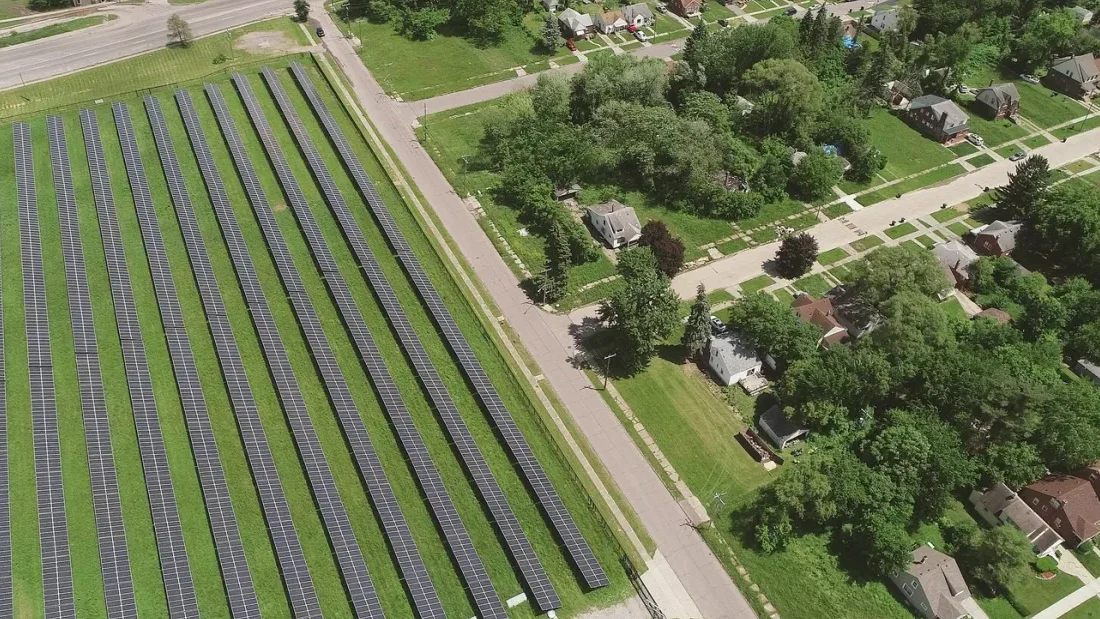

Ohio clean energy projects under an Inflation Reduction Act grant announced last month show how solar sited on closed landfills can reduce greenhouse gases, improve resilience and provide funding for other environmental goals.

Part of the $129.4 million grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency will add 28 megawatts of solar generation to a county central services facility and four former landfill sites in Cleveland and Cuyahoga County. A bigger chunk of the funding will bring 35 MW of solar and 10 MW of battery storage to a brownfield site in Painesville in Lake County, which will let the city close a coal-fired peaker plant that dates back to 1908.

Representatives of the Cleveland, Painesville and Cuyahoga County governments, along with the EPA and others, met July 26 at Cuyahoga County’s 4 MW solar array in Brooklyn, Ohio, to discuss the grant and the work. Funding from the EPA grant will more than double the generation capacity of that landfill solar site, which has been in operation since 2018.

“In Northeast Ohio we’re going to see warmer, wetter, wilder weather in this region. And we have to do our part to address climate change,” said Mike Foley, director of sustainability for Cuyahoga County.

Funded projects under the grant are expected to eliminate the equivalent of 1 million metric tons of carbon dioxide over a 25-year period, with the largest cuts coming from deploying the solar projects in Cuyahoga County, Cleveland and Painesville, according to Valerie Katz, deputy director of sustainability for Cuyahoga County.

The biggest chunk of grant money will go to Painesville, which is in Lake County east of Cleveland. But the 28 MW of solar generation to be built in Cuyahoga County will have a big impact.

“This will triple our solar capacity in Cuyahoga County in the next five years,” Katz said.

The landfill and brownfield projects funded by the grant will do more than produce electricity. By avoiding pollution from fossil fuels, they’ll provide health and environmental benefits. They’ll also produce revenue.

Some of the revenue from the brownfield solar site in Painesville will fund natural habitat for pollinators, birds and other wildlife elsewhere on that site. The city plans to work with the West Creek Conservancy for that and other projects, including building public trails and creating access for fishing.

Cuyahoga County also plans to use revenue from its sites to deploy more solar, Katz said. The added solar, in turn, can help develop microgrids to boost resiliency.

While closed landfills provide plenty of open space, they also are often capped by membranes made from clay or other materials that cannot be damaged without risking environmental harm.

Solar arrays at these sites are feasible thanks to ballast systems, which have been fairly common for such uses for more than a decade. Huge concrete blocks anchor the solar array’s racks and panels. The blocks, or ballasts, support the array and protect it from wind.

“They’re not going through the cap, which works out great for us,” said Jarnal Singh, an environmental supervisor with Ohio EPA’s Twinsburg office in its division of materials and waste management.

Without holes in the cap, the solar array doesn’t provide a pathway for methane or other gases to escape from the landfill. Leaving the cap intact also avoids creating a pathway for water to get in and percolate through the waste. That liquid, called leachate, could pollute groundwater if it’s not collected and treated properly.

Ohio has 141 landfill sites that have been subject to the state’s post-closure care requirements, according to Anthony Chenault, the Ohio EPA’s media coordinator for its Central, Northeast and Southeast districts. The agency has approved four landfills for solar development so far and has had informal discussions about several more sites.

But other practical considerations and site-specific features control whether any particular landfill is suitable for solar development.

“Some factors that could determine viability of a solar installation include proximity to existing power lines, size of the landfill, condition of the landfill cover, ownership (public vs private), and accessibility for equipment and maintenance,” Chenault said via email.

A few years should have passed since a landfill was closed and capped, so some settlement and off-gassing has already taken place, said Scott Ameduri, president of Enerlogics Networks, which was the primary developer for the Cuyahoga County solar site. There also must be a financially sound owner willing to accept responsibility for the waste at the site, he said.

Just as importantly, the electricity will need somewhere to go and a way to get there.

“In Brooklyn, for example, we were fortunate that Cleveland Public Power is a municipal utility,” Ameduri said. Municipal utilities are generally more flexible about making arrangements to take and distribute power than investor-owned utilities, he noted. Community solar legislation, such as House Bill 197, could help change things on that front, he added.

Another option is to have a large off-taker for the electricity adjacent to or near the landfill. The 7 MW of new grant-funded solar power to be built on a landfill south of the IX Center in Cuyahoga County can go to the expo center or the nearby Cleveland Hopkins International Airport, Ameduri said. The general area is also under consideration for one of the Cuyahoga County utility’s microgrids.

Otherwise, a landfill solar project putting electricity onto the grid may require a go-ahead from the regional grid operator, which is PJM for Ohio. The process takes roughly three to five years and adds extra costs. “I’d rather spread that over a 100-MW project than I would for a smaller brownfield site,” Ameduri said.

For now, Cleveland, Painesville and Cuyahoga County are celebrating the EPA grant award.

“This investment will allow us right here in Cleveland to turn brownfields into bright fields,” said Mayor Justin Bibb.

UTILITIES: A growing number of Georgia companies with climate goals are frustrated that less than half of Georgia Power’s electricity is carbon-free, and although the utility plans to build more solar, it’s still adding new gas turbines and delaying closure of its coal plants. (Grist/WABE)

ALSO:

ELECTRIC VEHICLES:

SOLAR:

CLIMATE:

COAL ASH: A town less than two miles from the University of North Carolina looks to redevelop 10 acres of land containing 46,000 tons of toxic coal ash, but lawyers and community members warn its cleanup plan still won’t adequately protect the public from health risks. (Inside Climate News)

GRID: Houston Mayor John Whitmire promises to hold CenterPoint Energy “accountable” for widespread outages during Hurricane Beryl, but the mayor and city have little power to regulate the utility. (Houston Chronicle)

OVERSIGHT: Environmental lawyers say the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn a policy giving federal agencies deference to interpret laws could affect Virginia’s regulation of vehicle emissions but probably not its enforcement of clean water rules. (Virginia Mercury)

POLITICS:

SOLAR: Officials with an energy company discuss their plans to begin construction in 2026 on an 800 MW solar farm in Kentucky atop a massive former coal mine, saying the project will provide equitable access to renewables and training for “future-proof energy jobs” as the coal industry declines. (Yale Climate Connections)

GRID:

PIPELINES:

ELECTRIC VEHICLES: An Alabama community college receives a $2.4 million grant to expand a center to train workers how to install, test, operate and maintain electric vehicle chargers. (news release)

EMISSIONS:

HYDROPOWER: The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma council approves a resolution opposing an Oklahoma energy company’s proposed hydropower project. (news release)

POLITICS: The Democratic governors of Kentucky and North Carolina — both of whom have benefitted from electric vehicle investment linked to federal climate legislation — are among the top contenders to run for vice president with likely presidential candidate Kamala Harris. (E&E News)

COMMENTARY:

PERMITTING: After two years of talks, Independent Sen. Joe Manchin and Republican Sen. John Barrasso agree on a permitting reform bill that would pave the way for increased renewable energy and fossil fuel development. (The Hill)

ALSO: Advocates criticize the energy permitting legislation, saying it is a “giveaway to the fossil fuel industry.” (Common Dreams)

POLITICS:

NUCLEAR: A startup looks to build a series of identical next-generation nuclear reactors throughout the country, targeting 6 GW of deployment by the mid-2030s. (Utility Dive)

SOLAR:

COURTS: Baltimore officials say they plan to appeal a circuit court judge’s decision to dismiss their climate deception lawsuit against more than two dozen fossil fuel companies. (Daily Record)

UTILITIES:

EFFICIENCY: Homebuilders claim a Kansas City ordinance requiring certain energy efficiency standards is slowing construction in an already tight housing market, but advocates say the numbers they’re using are misleading. (The Beacon)

RENEWABLE ENERGY: While new state measures and federal funds are helping smooth the way for substantially more solar in Pennsylvania, “fossil fuels aren’t going anywhere” amid pro-carbon capture and hydrogen production policies. (Spotlight PA)

ALSO: Massachusetts lawmakers are racing to find common ground on notable climate legislation focused on renewable energy permitting and siting reform, but there are “significant differences” between the state House and Senate versions of the bill. (RTO Insider, subscription)

NUCLEAR: The firm decommissioning the Pilgrim nuclear plant says it may appeal a decision by Massachusetts regulators not to let it discharge 1.1 million gallons of radioactive wastewater into the Cape Cod Bay. (CommonWealth Beacon)

COURTS: The Conservation Law Foundation says it intends to sue Vermont over the alleged failure of the state natural resources agency to follow a climate emissions law, saying the state used a faulty analysis to claim it’s on track to meet the first goal. (VT Digger)

POLITICS: Republicans highlight Vice President Kamala Harris’ support for a fracking ban during her 2020 presidential run as they make a case against her in Pennsylvania, while labor leaders highlight how climate and clean energy action can benefit workers in the state. (Axios, E&E News)

SOLAR: Environmental advocates are worried about the amount of woodland that is being clear-cut for utility-scale solar projects across New England, both over the emissions generated and the conservation loss. (Mongabay)

ELECTRIC VEHICLES:

GRID: Maine plans to grant $6.6 million to utilities and technology providers to undertake grid resilience projects across the state. (WABI)

TRANSIT: Baltimore’s light rail transit system has low ridership, but those who utilize the service say it’s their only way to get around. (Baltimore Sun)

WIND:

WORKFORCE: Two Maine solar installers form a workforce development partnership to ensure enough electricians are trained up to keep up with a statewide retirement problem. (news release)

OIL & GAS: As the U.S. shifts toward renewables, the Tennessee Valley Authority doubles down on gas generation with eight newly proposed gas-fired plants since 2020, including a planned 500 MW natural gas-fired power plant in Mississippi. (WPLN)

ALSO:

WIND:

ELECTRIC VEHICLES: An all-Republican school board in North Carolina votes to cancel a contract with Duke Energy for three electric school buses. (Port City Daily)

PIPELINES: Virginia regulators fine the Mountain Valley Pipeline $30,500 for nearly two dozen erosion and sediment control violations during a three-month period before it began operations. (Cardinal News)

NUCLEAR: The founder of a failed Appalachian indoor farming company has re-emerged as the cofounder and CEO of a startup that wants to deploy a 6 GW nuclear-fission reactor fleet by the mid-2030s. (Canary Media)

EFFICIENCY: A study finds nearly half of families in Memphis, Tennessee, face high energy burdens, paying at least 6% of their income toward energy bills due to low income, inefficient housing and outdated appliances. (Citizen Tribune)

COAL: Alabama receives a $20 million federal grant to rehabilitate abandoned coal mines. (WIAT)

GRID: Texas officials launch an investigation of CenterPoint Energy over poor communication and its slow pace of response to power outages caused by Hurricane Beryl. (Texas Tribune)

OVERSIGHT:

CLIMATE:

POLITICS:

NUCLEAR: The nation’s top nuclear regulator says a decommissioned Michigan nuclear plant could reopen by August 2025 if an environmental review remains on schedule and is approved. (MLive)

WIND: Wind development continues to divide residents in Midwest states, as misinformation leads to restrictive local regulations and local economic benefits can take years to materialize. (Associated Press)

ELECTRIC VEHICLES: Businesses in popular northern Michigan tourist towns are helping to fill gaps in electric vehicle charging infrastructure by hosting onsite chargers. (Bridge)

GRID: Utility regulators in Michigan, Indiana, Minnesota and Illinois sign a letter supporting a recent federal transmission order that they say will give states a larger role in transmission planning and cost allocation. (Utility Dive)

UTILITIES: A recent event in Detroit featured a panel of DTE Energy customers who discussed the emotional toll that power outages have had in an effort to promote community-owned power. (Planet Detroit)

PIPELINES: The Summit carbon pipeline developer says the delay in its plan to re-apply for a permit in South Dakota is unrelated to an upcoming referendum on a state law that critics say benefits pipeline companies. (South Dakota News Watch)

SOLAR:

EFFICIENCY: Northern Michigan utilities invest hundreds of thousands of dollars in residential and commercial energy efficiency rebates to reduce customer costs and power demand. (Record-Eagle)

COMMENTARY: