Utilities tend not to be big fans of rooftop solar, which eats into their revenues by reducing customer reliance on the power grid. A new Ohio lawsuit spotlights the tension between utilities and customers over the clean-energy technology.

The case deals with a monthly charge imposed by the city of Bowling Green’s municipal utility on its few customers with solar panels on their rooftops. Customers who use batteries to store surplus solar power pay even more.

Residents Leatra Harper and Steven Jansto claim the charge, which for them amounts to roughly $56 per month, is an unlawful “tax or penalty.” When combined with the city’s partial payment for power fed back into the grid, it almost doubles the payback period for their $37,000 solar system, the couple said.

The city argues the fee is needed to make sure other customers don’t subsidize those with rooftop solar. As households that produce some of their own electricity buy less from the utility, they pay less for fixed costs built into its retail rates, such as staffing, grid equipment, and maintenance. The utility would then look to other customers to make up the difference.

The situation echoes “cost-shift” arguments that have dogged rooftop solar around the nation. It could also be a preview of a statewide battle to come as the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio gears up to review and revise its net-metering rules, which determine how solar owners are compensated for the energy they send to the grid. Municipal utilities like Bowling Green are not subject to these rules, but the dynamics around the fairness of rooftop solar rates are similar in either case.

For their part, Harper and Jansto installed rooftop solar panels and battery storage at their home in 2019 and 2020 with hopes of lowering their electric bills and cutting their carbon footprint. The investment will eventually pay for itself because they now buy less electricity from the utility while getting some credit for excess fed back to the grid.

“We could get to near net-zero with a cost up front, but with a payback,” said Harper, who is managing director of the FreshWater Accountability Project, an environmental group.

Residential solar doesn’t just help those who invest in it.

“Rooftop solar helps to provide electricity locally. It reduces overall demand,” said Mryia Williams, Ohio program director for the nonprofit group Solar United Neighbors. That means less wasted energy because the power doesn’t need to travel as far as imported electrons, and it lowers stress on the transmission system as climate change exacerbates extreme weather and energy demand grows.

Energy fed into the grid from homeowners’ renewable energy systems can save other customers money, too.

“The highest demand periods on the grid tend to coincide with times when residential solar power is producing at its peak,” said Tony Dutzik, an associate director and senior policy analyst for the Frontier Group, a sustainability-focused think tank. “Those tend to be the times that utilities spend the most money to provide power for their customers.”

The health and environmental benefits of rooftop solar are “pretty obvious,” especially when excess energy offsets purchases from inefficient gas-fueled peaker plants, Dutzik continued. Less consumption of fossil fuels lowers greenhouse gas emissions and other pollution that is linked to multiple illnesses and more than 8 million deaths per year worldwide — problems that could worsen in the U.S. as the Trump administration rolls back climate policy.

Policymakers have “oftentimes undervalued the benefits that rooftop solar can bring, and when you fail to really account for the benefits, you tend to wind up in the situation where people think it’s not fair,” Dutzik said.

Along those lines, Brian O’Connell, utilities director for Bowling Green, said via email that the city adopted its $4-per-kilowatt monthly charge for installed renewable capacity “to ensure rooftop solar customers were paying for the electric service they were receiving, and that the rooftop solar customers were not being subsidized by non-solar customers.”

The rationale resembles an argument promoted by ALEC, the American Legislative Exchange Council, since 2014. The Center for Media and Democracy has long criticized the group for coddling the fossil-fuel industry while working to suppress the vote and stifle dissent.

Consumer advocates and some academics have made similar cases in California, whose solar capacity leads the nation for both rooftop and overall.

But Harper and Jansto were surprised when they learned Bowling Green adopted its “Rider E” charge roughly six months after work on their home’s renewable energy system wrapped up.

The utility had seemed friendly toward solar: Its website touts the significant share of its power that comes from renewables. Yet while the city aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, it does have a long-term “take-or-pay” contract to get about half of its electricity from the Prairie State coal plant in Illinois.

Legal and constitutional claims in the couple’s Sept. 19 complaint include unlawful and irrational discrimination. The City of Bowling Green filed its answer on Oct. 14, denying liability and asserting governmental immunity and other defenses.

O’Connell said the $4/kW rate for the charge resulted from a cost-of-service analysis by the municipal utility’s consultant, Sawvel & Associates. The city charges a general retail rate of about 13 cents per kilowatt-hour for any electricity it sells to customers. However, it credits rooftop solar owners just 7.5 cents per kilowatt-hour for whatever they supply to the grid.

O’Connell responded to Canary Media’s request for information about how the Rider E rate was calculated by sharing two spreadsheets. Each lists total savings or costs for the utility from a rooftop solar customer’s energy production, including what the utility saves by not paying other sources for capacity, transmission, and wholesale energy when customers feed excess power onto the grid.

But the documents don’t detail how the utility spends the solar surcharge. It’s unclear whether the rooftop solar fees are helping pay for the Prairie State coal plant: O’Connell’s response to Canary Media’s question merely noted the city still has to purchase energy from the electric market.

Harper and Jansto’s case will move through legal motions and pretrial fact-finding, called discovery, during the coming months. Meanwhile, advocates worry about the broader questions the case raises.

“We can look at it both ways with who’s supporting whom whenever rooftop solar is installed,” said Williams of Solar United Neighbors. In her view, “it’s hard to believe that it’s some sort of subsidized rate,” especially if solar customers get only partial credit for letting others use their excess energy.

Ultimately, Dutzik said, rate systems still should not discourage people from investing in renewable energy for their homes. Indeed, if high fees delay recovery of investments for too long, “fewer people are going to get solar,” Dutzik said. “And that is going to drive up costs for other consumers.”

This summer, an ammonia-powered ship completed its maiden voyage in eastern China, becoming the first of its kind to run purely on the carbonless compound. Around the same time, in Denmark, the shipping giant Maersk launched a big container ship that can use methanol, making it the fourteenth and largest vessel yet in the company’s growing low-carbon fleet.

Efforts like these are playing out worldwide as the maritime industry works to replace dirty diesel fuel in oceangoing ships, which haul everything from T-shirts and tropical fruit to solar panels, smartphones, and steel rebar. But the progress to date has been piecemeal, representing only a sliver of the world’s oil-guzzling freighters and tankers.

Up until last week, the United Nations’ International Maritime Organization appeared on the cusp of approving a strategy to supercharge shipping decarbonization worldwide. The plan was set in motion in 2015, after the U.N. adopted the Paris Agreement, clarifying the urgent need for countries and companies to reduce planet-warming pollution to zero.

“It sent a signal for the [maritime] industry to start thinking ahead,” said Narayan Subramanian, an expert on international climate policy and clean energy finance at Columbia Climate School.

In the ensuing decade, the IMO worked to hash out regulations that could jumpstart a universal transition toward cleaner ships. The agency landed on the Net-Zero Framework, which would require ships to use more low-carbon fuels and also establish a tax on carbon emissions — setting the first binding carbon-pricing scheme for an entire industry.

“This is not coming out of left field. It’s not being imposed overnight,” Subramanian said last week before IMO officials put the framework to a vote.

Yet on Oct. 17, after a full-throttle offensive from the Trump administration, the IMO moved to delay making any decision on the landmark decarbonization strategy by one year, keeping the industry locked in limbo. Many fuel producers, shipbuilders, and cargo owners have said they need reassurance that shipping is, in fact, charting a cleaner course before they invest billions of dollars in making new fuels and building related infrastructure.

“There is a lack of incentive globally for shipping operators to use clean fuels,” said Jade Patterson, an analyst for the research firm BloombergNEF. He said the framework would improve the business case for using hydrogen-based fuels like ammonia and methanol, which are significantly more expensive than oil- and gas-based fuels.

A smaller group of IMO members is meeting in London this week to drill down on the finer details of the proposed regulations, which will come up for a vote again in October 2026. But it’s unclear whether any global environmental agreement can succeed while President Donald Trump is in office.

In the meantime, the industry will continue guzzling greater volumes of fossil fuels as shipping activity grows over time.

Tens of thousands of merchant ships ply the oceans every year to haul roughly 11 billion metric tons of goods. Together, they’re responsible for about 3% of the world’s annual greenhouse gas emissions.

The Net-Zero Framework was meant to give teeth to the nonbinding climate goals that IMO adopted in 2023. Member countries set near-term targets for reducing cargo-ship emissions by at least 20% by 2030, compared to 2008 levels. They also called for curbing emissions by at least 70% by 2040, and for reaching net-zero emissions “by or around” 2050.

Countries further agreed to have 5% to 10% of shipping’s energy use come from zero- or near-zero-emissions fuels and technologies by 2030.

Current adoption of those fuels amounts to a tiny droplet in an ocean’s worth of oil. Much of it is driven by voluntary efforts by companies like Maersk, which face pressure from investors and customers to clean up their fleets. Meanwhile, regional environmental policies are taking effect. European nations and China are working to rein in ship-engine pollution, and they and other countries — including Brazil, India, and, until recently, the United States — are steering government funding into hydrogen production.

Hydrogen is a key component of ammonia and methanol — two common chemicals that can be used in engines or fuel cells. How clean those fuels actually are depends largely on whether the hydrogen is produced using renewables, or the way that most H2 is made today: with fossil fuels. Renewable diesel, another lower-carbon option for powering vessels, also uses hydrogen in its production process.

If every project to produce green ammonia, green methanol, and renewable diesel comes online as planned, and if the fuels only go toward powering ships — not airplanes or vehicles or to other uses — they would make up less than 20% of global shipping’s fuel needs in 2030, which are expected to reach 290 million metric tons that year, Patterson said.

Those are two enormous “ifs.” Many of the announced fuel projects are facing serious headwinds, including high inflation, soaring production costs, and the Trump administration’s steep tariffs and clean-energy funding cuts. IMO’s recent decision to punt on its net-zero vote only deepens those challenges.

Last year, Danish energy giant Ørsted canceled plans to build a green-methanol plant in Sweden, citing weaker-than-expected interest from the maritime sector. Another Ørsted methanol project in Texas is facing uncertainty after the U.S. Department of Energy in May revoked an award of up to $99 million for the facility, as part of sweeping cuts to the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations. In the Netherlands last month, Shell said it is abandoning construction on a biofuels plant in Rotterdam owing to the fuel’s lack of competitiveness.

“What we’ve seen is that this lack of demand and the shift in policy has led many projects to fold,” said Ingrid Irigoyen, president and CEO of the Zero Emission Maritime Buyers Alliance. “But that’s not because they weren’t good projects. These are good fuels that we need, and which are vastly scalable.”

The buyers alliance is a nonprofit group of about 50 multinational companies that helps negotiate clean-fuel contracts — including for waste-based biomethane — between producers, vessel operators, and firms that put their goods on ships. Irigoyen said such voluntary initiatives are meant to be a “catalyst” that helps to scale production and bring down costs of alternative fuels, not the sole engine of shipping decarbonization.

“We can’t do it alone,” she added.

Even as shipping-industry groups and climate experts push for a global policy, there’s still widespread disagreement about how the framework should work in practice. Environmental groups oppose including crop-based biofuels, like soy and palm oil, given that their production can lead to forest loss and increase overall emissions. Policy analysts note that the ripple effects of higher fuel costs and carbon taxes across supply chains could disproportionately affect small and developing economies.

As IMO members navigate those questions, shipbuilders and owners are holding their breath for the answers.

This year, the number of new orders for alternative-fueled vessels has markedly declined compared to last year as companies adopt a “wait and see” approach, according to Jason Stefanatos, global decarbonization director at DNV.

In September, the advisory firm recorded no fresh orders for ships capable of running on methanol or ammonia, though nearly 360 methanol ships and nearly 40 ammonia ships are on the books through 2030.

Subramanian noted that vessels and port equipment are often designed to last for decades, and that many shipping firms are at the point of deciding whether to invest in a status-quo fleet or the next, cleaner generation.

Decarbonization “is a very natural opportunity to upgrade shipping infrastructure that’s otherwise been around for 30 or 40 years,” he said. “And the investment-certainty piece is key to that.”

The Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations was supposed to be a launchpad for ambitious projects to help America lead the way on cleaner power and manufacturing. Now it’s been reduced to a shell of itself.

As the Trump administration slashes spending and fires workers across the federal government, the U.S. Department of Energy has emerged as one of the hardest-hit agencies — and perhaps no other of its divisions has been singled out as deliberately as OCED.

It’s a dramatic reversal for the four-year-old office. During the Biden administration, Congress endowed it with nearly $27 billion to try to scale up cutting-edge technologies that could curb planet-warming pollution from industrial facilities and power plants. Trump officials have in recent months hollowed out the office, canceling billions in previously issued awards for everything from low-carbon chemical manufacturing to rural energy resiliency, while also dismissing over three-quarters of its employees.

The situation is best summarized by the budget the White House has requested for OCED for the next fiscal year: $0.

Experts and insiders warn that the tumult within OCED and the DOE more broadly is eroding the private sector’s trust in the federal government and its ability to drive energy innovation.

“The administration has really created a chilling effect on the willingness of future early-stage technology developers to work with the Department of Energy,” said Advait Arun, a senior associate for energy finance at the Center for Public Enterprise, a nonprofit think tank.

Ultimately, that will stifle investment not only in the clean energy sectors the Trump administration dislikes but in those it has championed as well, such as advanced nuclear and geothermal. Former OCED staffers and contractors, who were granted anonymity to speak freely, told Canary Media that the disruption is a major setback for America’s efforts to launch the world’s next generation of energy technologies and industries.

“We are eliminating ourselves as a leader in the clean energy space, especially for the industrial complex,” one person said. “What I’m seeing is China is about to slip right into that position. Just logically and economically, I don’t understand the steps that are being taken.”

Congress created OCED in December 2021 to help deploy first-of-a-kind projects at commercial scale. The idea was for the government to absorb some of the risks and provide early capital to usher companies across the valley of death that lurks between promising research pilots and real-world operations that can move the needle on decarbonization.

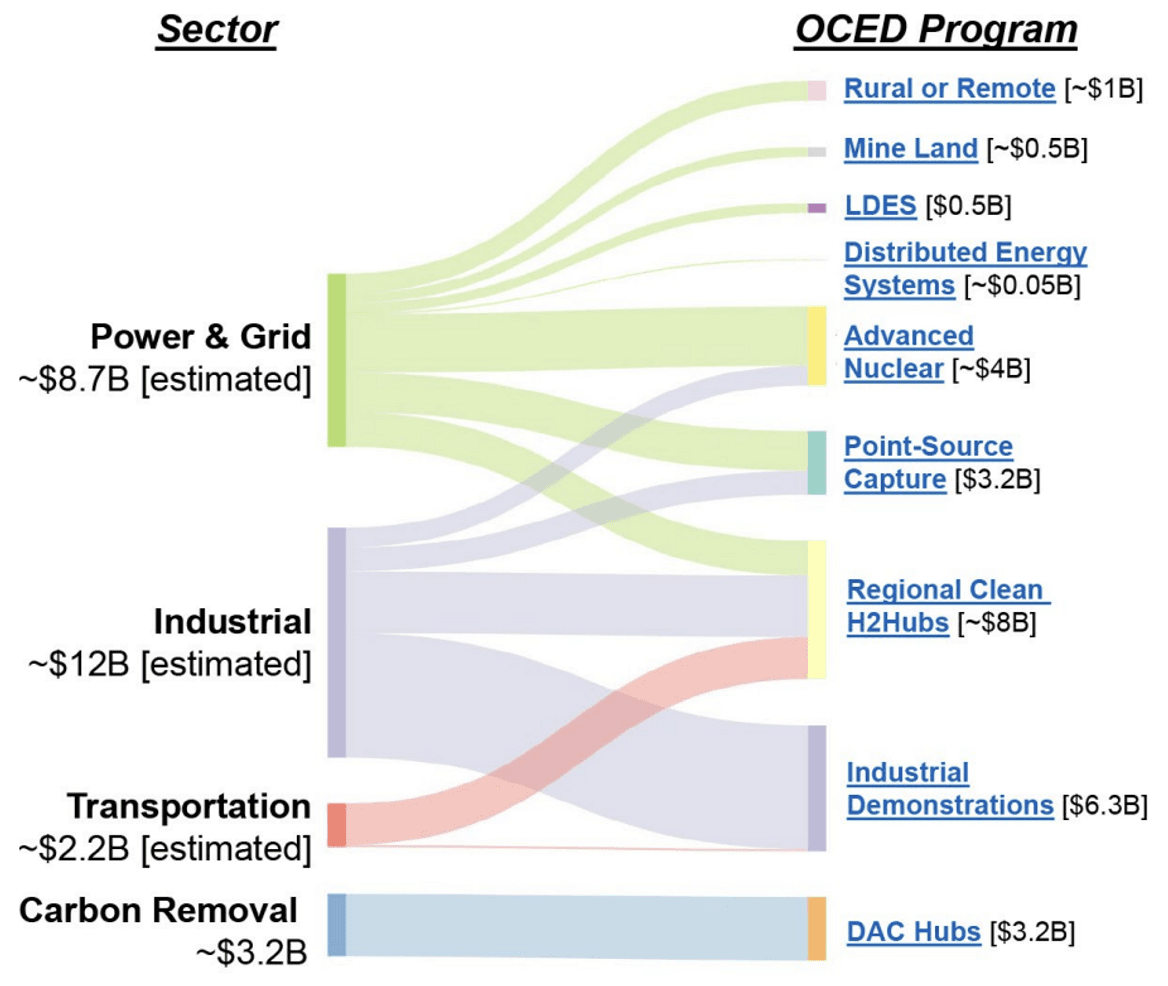

The 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law provided OCED with about $21 billion over five years to scale up emerging technologies like small modular reactors and long-duration energy storage, and to advance ambitious “hubs” for producing hydrogen fuel and capturing carbon dioxide from the sky and smokestacks. In 2022, Congress gave OCED an additional $5.8 billion through the Inflation Reduction Act to help decarbonize U.S. manufacturing of materials like steel, cement, and chemicals.

“A lot of this stuff is a chicken-and-egg situation, where the private sector doesn’t want to come in [and invest] yet because it’s not proven,” said Zahava Urecki, a senior policy analyst with the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Energy Program.

“But we need the technology to go through this [demonstration] process in order to make sure it becomes proven, so that eventually we can have this in society,” she added. “And that’s where the federal government plays a key role.”

Over the course of three years, the office selected 116 projects in 42 states to receive over $25 billion in federal funding. For most awards, participating companies were required to cover at least 50% of total costs themselves — meaning the office expected its portfolio to spur nearly $65 billion in private investment, in addition to creating potentially hundreds of thousands of jobs.

Among the biggest winners were seven regional hydrogen hubs and two major direct-air-capture initiatives that would remove CO2 directly from the sky. The choices were not always broadly celebrated, and critics raised concerns that the hydrogen and carbon-capture initiatives in particular would do more harm than good for the climate by propping up unproven, energy-intensive projects involving fossil-fuel companies.

But other OCED picks garnered more public applause — and supported industries that President Donald Trump had flagged as priorities. In 2024, the office selected Cleveland-Cliffs for an award of up to $500 million to begin lower-carbon steel production in Middletown, Ohio, the hometown of Vice President JD Vance. Another manufacturer, Century Aluminum, got up to $500 million to help it build the nation’s first new aluminum smelter in decades, which would be powered by carbon-free electricity.

Former OCED staffers said they attempted to brief the incoming Trump administration on the office’s portfolio and to explain how they could support the president’s stated goals of boosting “American energy dominance” and “advancing innovation.”

However, from the time Trump took office on Jan. 20, “It became pretty clear that it didn’t really matter,” a former employee said.

It was quickly evident that Trump would, in fact, be adopting the right-wing policy platform Project 2025 after trying to distance himself from it on the campaign trail. The blueprint — which outlines ways to erase federal spending — called for eliminating “all DOE energy demonstration projects, including those in OCED,” in order to avoid “distorting the market and undermining energy reliability.”

For one staffer, “it all started crumbling” on Day 1, when the White House issued an executive order to halt federal work on “diversity, equity, and inclusion” — a measure that affected OCED’s grant recipients. Under former President Joe Biden, the office required participants to create community-benefit plans to ensure the billions in taxpayer dollars went to projects that included neighbors in the planning process and supported local economies. Under Trump, the strategy became a liability.

A blitz of federal funding freezes and layoffs — and court reversals and injunctions — then ensued, creating chaos across federal agencies and for all the outside companies that hold or held government contracts. In late January, the White House extended federal workers a “deferred resignation offer” that would allow people to resign from their jobs and go on leave with pay through Sept. 30, the end of the fiscal year.

Few OCED staffers initially took the offer. But after several months of chaos, about 77% of workers at OCED signed the deal when the White House extended it again in April. Insiders say that figure is likely even higher now. Across the DOE, some 3,200 employees within the agency’s roughly 17,000-person workforce opted to leave.

“That’s when folks at OCED actually started to realize it was going to be personnel changes that would first impact the projects, and not the program cuts,” according to a former employee.

On May 15, about a month after the staff exodus, Energy Secretary Chris Wright said the DOE would begin scrutinizing federal grants to “identify waste of taxpayer dollars.”

The agency started requesting additional information for 179 awards totaling over $15 billion, with a focus on large-scale commercial projects. Wright claimed that these awards were “rushed out the door, particularly in the final days of the Biden administration,” and required further review to ensure that individual projects were “financially sound and economically viable.”

Less than 3% of the over $25 billion in OCED’s awards portfolio had actually been paid to projects as of March 31, in part because larger grants were meant to be doled out in tranches over a long development timeline, according to EFI Foundation, a nonpartisan organization led by Ernest Moniz, who served as energy secretary during the Obama administration.

Project developers interviewed by EFI claimed that, contrary to Wright’s statement, OCED’s “due diligence was more rigorous than what private-sector investors would conduct” and that, rather than undergo the office’s laborious process, “faster decisions would have better aligned with developer timelines,” the foundation said in a June report.

Wright didn’t wait long to begin nixing projects. In late May, he announced the termination of 24 awards issued by OCED totaling over $3.7 billion, including funding for carbon capture and sequestration and projects within the office’s Industrial Demonstrations Program that aimed to reduce emissions from iron, cement, glass, and chemicals production.

“These clean energy projects were enshrined into law by bipartisan majorities and represent the will of Congress,” Sen. Martin Heinrich, Democrat from New Mexico, said in a recent statement to Canary Media. Heinrich and other congressional Democrats sent a letter to Wright on Sept. 9 accusing the DOE of undertaking a “haphazard, disorganized, and politically driven” cancellation process.

More funding cuts arrived earlier this month, when the DOE said it was slashing 321 grants for projects almost entirely in states that voted for Democratic nominee Kamala Harris in the 2024 presidential election. A spreadsheet of the cuts lists 11 newly affected OCED projects totaling nearly $2.5 billion, including for two major hydrogen projects planned in the Pacific Northwest and California. The October list also repeats five OCED-backed initiatives that first appeared in the May announcement.

Project developers have said they’re appealing the award terminations and are in continued talks with the DOE. Still, it’s unclear how much capacity the office has anymore to helm those discussions.

Wright said in an Oct. 3 interview that more cancellations would follow, and early last week rumors swirled about a second spreadsheet that appeared to outline deeper cuts for carbon-removal projects, hydrogen hubs, and other OCED projects. The nature of the list remains unclear, but if it proves to be a signal of cuts to come, it would cancel another $6.1 billion in awards from OCED.

The project areas that have yet to be cut — or to appear on any potential hit lists — include advanced nuclear energy and critical minerals. Additionally, the energy agency said it has started tapping OCED’s authority to make some new grants for Trump’s favorite energy source: coal-fired power plants. Should the office shutter, these awards would likely be managed by other divisions within the DOE.

Alex Kizer, a senior policy advisor at EFI, noted that gutting OCED won’t end America’s efforts to decarbonize heavy industries.

In the case of cement and steel, demand for low-carbon materials is growing within U.S. and global markets as tech giants look to build less carbon-intensive data centers, and as state governments and European and Chinese regulators work to rein in industrial pollution. Still, losing grants — and the DOE’s seal of approval — will undoubtedly make it harder and more expensive for companies to raise private capital for commercial-scale projects. Stifling the DOE’s role as a gatherer and publisher of real-world lessons could further slow progress, Kizer said.

“The potential for breakthrough across different energy sectors is so significant,” he said of OCED’s work, noting that “a relatively small investment from taxpayers could have an enormous benefit to taxpayers over time,” in terms of delivering cleaner, more reliable energy. “Who says no to that?”

Barbara Kelley remembers when her car and windows were routinely coated with a thin film of coal dust that had drifted over from the power plant on the edge of her neighborhood in Salem, Massachusetts. She remembers the noise as a conveyor belt lifted the coal into the building. She also remembers how pleased she was when the community started to discuss the possibility of building an offshore wind terminal on the site when the plant eventually closed.

“The coal plant — it worked, it gave us energy, but it was time to change,” Kelley said. “My reaction was, having a wind port is part of having wind energy — and that’s a good thing.”

In the years since the coal plant shut down in 2014, Kelley and many other community members have worked to promote the goal of transforming part of the property into a staging ground where wind turbine blades, tower sections, and nacelles can be prepared for transport to offshore construction sites south of Cape Cod and north in the Gulf of Maine. The vision was to turn Salem Harbor, one of the country’s oldest ports, into a linchpin of the then-burgeoning offshore wind industry and provide an economic boost to some of Salem’s most disadvantaged residents.

Last year, that dream seemed close at hand. City and state leadership had embraced the idea. The state had promised a hefty investment, and the Biden administration had awarded the project a sizable grant. Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey attended a groundbreaking ceremony for the development in August 2024, and operations were expected to begin in 2026.

Project developer Crowley had agreed to pour nearly $9 million into a community benefits agreement that included job training, childcare, emergency services, and local sustainability and resilience efforts. Planners estimated construction and operations would create hundreds of jobs. And the whole process of bringing the idea to life gave community members a sense of agency and hope for their city.

Then this August the Trump administration announced that it would cut off $679 million in federal funding for offshore wind ports. The move was part of President Donald Trump’s ongoing attacks on offshore wind, the impacts of which are being felt far beyond the nascent sector. Now, like those in so many communities across the country, the people of Salem find themselves facing the fallout of national political priorities, and wondering whether more than a decade of work will ever bear fruit.

“I feel like we’re all a little bit in the dark still,” said Lucy Corchado, a local activist who was part of the group that negotiated the community benefits agreement. “I hope we hear some good news, but I’m not sure that’s going to happen.”

Community advocates first started floating the idea of building a wind port on Salem Harbor roughly 15 years ago. At the time, plans were underway to build a commercial wind farm off Cape Cod, and the coal plant’s closure looked likely. The advocates saw a promising future for the large industrial waterfront parcel in what seemed to be a growing energy sector.

Once the epicenter of the spice trade in early America, Salem has a deepwater port that today serves mostly recreational boaters, tourist outings, and the occasional cruise ship. Though the city is home to a hospital, university, and thriving hospitality sector, it also has a median household income well below the average in most surrounding towns and statewide.

When the owner of the coal plant proposed building a natural gas–burning facility on the site, activists from Salem Alliance for the Environment, or SAFE, were skeptical of replacing one fossil fuel with another. However, they decided not to oppose the plan for a new, smaller plant and to instead push for the rest of the property to be used for an offshore wind port that could both contribute to the decarbonization of the grid and create new opportunities for local residents.

“It wasn’t that we were really supportive of the gas plant, but we had bigger dreams of a wind port coming into town,” said SAFE founder Patricia Gozemba. “Our dream played out.”

In 2022, then-Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, announced the state would make a $75 million investment in the port, and the project was also awarded a $34 million grant from the federal Port Infrastructure Development Program. Two years later, the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center bought 42 acres of the former coal plant property, with the intention of leasing it to energy and marine developer Crowley. The City of Salem acquired five adjacent acres.

The plans enjoyed widespread support in the city.

“We’re a uniquely progressive community,” said SAFE executive director Bonnie Bain. There was no organized opposition to the wind port idea beyond occasional grumbling by Facebook commenters, she said.

As negotiations between Crowley and the city got underway, SAFE and other groups started to worry that, despite their longstanding advocacy for the project, important community input was missing from the process.

“This wasn’t just a wind port — it was an investment in the community,” Bain said. “We want to make sure that when we build projects that they enhance the community.”

Advocates raised their voices, submitting testimony for state and local proceedings, attending planning board meetings, and hosting educational webinars about offshore wind. In 2023, SAFE and several Salem neighborhood associations and civic groups formed a coalition to ask for a seat at the bargaining table as the city and developer hammered out the community benefits agreement.

The coalition was determined to make sure that the project didn’t harm nearby residents and created opportunities for some of the city’s disadvantaged populations. The group met once a week — Thursdays at 4 p.m. — for a year to discuss strategy, write letters to the media, and plan for local and state meetings. Salem Mayor Dominick Pangallo agreed to include two coalition members — Kelley, representing the Historic Derby Street neighborhood adjacent to the planned port, and Corchado, representing The Point, a largely immigrant, lower-income neighborhood nearby — in the community benefit negotiations.

“We kind of pushed our way to the discussion table to make sure they heard what we were looking for,” Corchado said.

The parties struck a deal that included a range of measures. The city’s public schools were set to receive $40,000 annually for technical and vocational education programs and another $50,000 per year to expand prekindergarten childcare to help parents attend job training. Crowley also committed to offer paid apprenticeships and internships, help graduating students find jobs in the industry, and fund scholarships for local workers to access relevant training opportunities.

When Trump was elected in 2024, some port supporters held out hope that the project would escape the president’s well-known hostility to offshore wind. Corchado, however, was concerned from the beginning.

“We were so far along and the funding has already been secured. It was like, maybe it’s not going to be that bad,” she said. “But, yeah … it’s what I was worried about.”

The news on Aug. 29 that the federal funding would be terminated was an enormous disappointment for proponents. It also left them with questions about whether the lost funds would scuttle the plan entirely, force the developer to change course, or merely delay implementation. Crowley will say only that it is reviewing the action and determining next steps. The city of Salem is also figuring out what to do now.

“We are still working to pursue all avenues to address the funding termination,” the mayor’s office said in a statement. “That includes working to get it restored or, failing that, looking at how we could revise the project plan to account for the loss of what was around 10% of the expected construction costs for the port.”

Community members are feeling somewhat adrift as the concrete plans they invested so much time in become increasingly uncertain.

“It wasn’t necessarily surprising,” Bain said. “But it’s still dizzying when it actually happens.”

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy, and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

During a recent visit to a Long Island power station, U.S. Department of Energy Secretary Chris Wright criticized Biden-era policies that supported the development of renewable energy sources.

“There was a lot of that money allocated under the Biden administration that was to encourage business and utilities to … spend money to make electricity more expensive and less reliable,” Wright said during a press conference.

The next day, the Trump administration announced the termination of 321 awards, claiming $7.5 billion in cuts for clean-energy projects. Inside Climate News recently reported that many of these awards were already past their end date.

Empire Clean Cities, which promotes the advancement of alternative fuels and alternative-fuel vehicles to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, was among the organizations that had its funds cut.

The Manhattan-based nonprofit will lose more than 90% of the funds for its $1.7 million award. So far, Empire Clean Cities had received only $162,631 of its award for a project designed to reduce emissions in Hunts Point in the Bronx, according to federal spending data. Largely due to truck traffic, this neighborhood has an annual child asthma hospitalization rate double the citywide average.

“It’s where folks live and work, and so they see every day the impact of truck traffic emissions on their air quality, on their health,” said Joy Gardner, the executive director of Empire Clean Cities. “This was a real opportunity to make a drastic change in just the general quality of life.”

Hunts Point attracts a high volume of freight traffic partly due to its proximity to food centers, including the Hunts Point Food Distribution Center. The city estimates that the center distributes around 4.5 billion pounds of food every year.

Empire Clean Cities is on the cusp of publishing an electrification plan for Hunts Point, with engagement from local businesses, communities, and city agencies. The plan would offer a pathway to electrification for vehicles operating in the neighborhood—and subsequently help alleviate the health issues many residents face.

Though Gardner said the plan is likely to still be published, other aspects of the plan could be delayed or may not happen at all. The nonprofit planned to install six fast-charging electric ports in the neighborhoods, for personal and freight vehicles, according to Gardner.

Empire Clean Cities also planned to provide technical assistance to businesses looking to electrify their truck fleets and information sessions for community members who might want to buy an electric vehicle. According to federal spending data, the nonprofit would “undertake an extensive suite of community outreach activities designed to break down the knowledge barriers preventing [electric vehicle] adoption in the neighborhood.”

“It’s really disappointing not to be able to take this over the finish line, especially with just a year left on the grant,” said Gardner. “We would have been able to do a tremendous amount with that.”

In a statement about the grant cancellations, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul (D) said, “These cuts directly impact local businesses and major companies, putting workers out of jobs, shuttering factories, and slowing our state’s economic progress.”

In response to questions from Inside Climate News, Ken Lovett, Hochul’s senior communications advisor on energy and environment, wrote that the announcement “came as no surprise given the Trump administration’s full-on assault on clean energy.”

The Trump administration announced the termination of 321 grants on Oct. 2. An Inside Climate News analysis of federal government spending data for the awards found that only 188 were still active, according to their stated end dates, at the end of September.

ICN subtracted money already sent to recipients from the sums obligated to be spent, calculating a total of $4.87 billion in cuts, roughly two-thirds of the dollar amount announced by the Department of Energy.

For recipients based in New York state, 20 awards were still active when the Trump administration announced the cuts. After accounting for the money already distributed, the state lost out on about $146 million.

But for Hochul, the grant cuts seem to be just the latest setback to her plans to deliver on the state’s lofty climate goals and address energy concerns. She has recently admitted that New York is unlikely to meet its climate targets, drawing the ire of many residents.

Hochul says she remains committed to reducing emissions in the state and has invested considerable funds toward that goal. She recently allocated $1 billion to clean-energy projects and emissions-reduction efforts and has directed the state-owned utility, the New York Power Authority, to build at least one new nuclear plant by 2040.

At a Brooklyn church in early September, the advocacy group Public Power NY hosted a People’s Hearing for Public Renewables, where officials, environmentalists, and a few dozen New York residents discussed the state’s renewable-energy plans and expressed disappointment with Hochul’s progress.

“We have a movement behind us that is fighting for something better,” said state Sen. Jabari Brisport, a Democrat who represents a district in Brooklyn. “We have a governor who wants to drag her feet.”

New York’s Climate Act requires the state to achieve a 40% reduction from 1990 levels in economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and an 85% reduction by 2050. The act also requires that 70% of the state’s electricity come from renewable sources by 2030.

Residents were advocating for the New York Power Authority to build 15 gigawatts of renewable energy by 2030, which they view as necessary to meet the state’s goal of net-zero emissions from the electricity grid by 2040. Currently, the utility plans to build 7 gigawatts of renewable energy, despite state law requiring it to fill all gaps in electricity generation left by the private sector.

“Hurricane Ida completely destroyed my district,” said former Democratic U.S. Rep. Jamaal Bowman, whose district included White Plains and Yonkers. “We need a governor with human-centered leadership … and if not, we need a new governor.”

Much of the focus on achieving these climate goals has been on electrifying building heating and cooling with heat pumps and moving away from gas systems. In 2023, the state passed the All-Electric Building Act, which mandated that most buildings use electric appliances, and the all-electric standard was written into the state building code in July.

The legislation effectively requires most new buildings to be completely electric — so no gas heating or cooking. A similar law was passed in New York City in 2021.

At a recent press conference, Wright, the federal energy secretary, alluded to the “many productive dialogues” he has had with the governor, and said that two proposed gas pipelines, which would pass through the state and which state officials have rejected in the past, were “already planned” and would “lower the cost of heating.”

There has been speculation, fueled by a May post on X by Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum, that Hochul “would move forward on critical pipeline capacity.” The implication was that this was a trade-off for allowing the Empire Wind offshore wind project south of Long Island in the Atlantic Ocean to proceed after the administration halted construction.

Within a month, two previously rejected gas pipelines — the Constitution pipeline and the Northeast Supply Enhancement pipeline, or NESE — entered the regulatory process once again. Hochul has denied that she made a deal with the White House, but the Trump administration has said that she “caved” and agreed to allow the pipeline construction, according to Politico’s E&E News.

The Constitution pipeline, which the state rejected in 2016, would run from Pennsylvania’s Marcellus shale fracking sites to upstate New York. The NESE pipeline would extend an existing pipeline, building off the coast of New Jersey and Staten Island to eventually connect with existing pipes in Queens, and add gas infrastructure to Pennsylvania. The state has rejected it three times.

In July, National Grid, the gas utility that serves Staten Island, Long Island, and parts of Brooklyn and Queens, added the NESE pipeline to its long-term gas plan as an addendum.

The utility has to file a long-term gas plan as a result of a dispute with former Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D). The heart of the 2019 dispute was, ironically, an earlier proposal for the NESE pipeline, which the Department of Environmental Conservation had rejected due to its potential impacts on water quality.

The rejection led to a standoff between the utility and state officials, with National Grid refusing to connect customers to gas lines. The dispute only ended because Cuomo threatened to suspend the utility’s license to operate in the state. In the end, National Grid agreed to periodically file a long-term gas plan for review by the state’s Public Service Commission, which regulates utility rates.

While reviewing the utility’s plan for the future last month, members of the Public Service Commission found that the NESE project would help the state meet the energy needs of its residents and businesses, particularly in the wake of Winter Storm Elliott in 2022. A report by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission found that some areas of New York were at extreme risk of experiencing gas shutoffs at one point during the storm.

But many New Yorkers were dismayed by the commission’s choice, which has no regulatory authority over the pipeline, but which many believe could signal to the Department of Environmental Conservation that the pipeline is necessary and that it should approve its water permit.

“We are in a week-by-week, hour-by-hour, fight to hold [Hochul] off and keep her from approving this thing,” Pete Sikora, the climate and inequality campaigns director with New York Communities for Change, said about the fight to stop the NESE pipeline.

Several public officials, including Staten Island Borough President Vito Fossella (R) and U.S. House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D), spoke out against the pipeline, as did the city of New York. Water-quality concerns and fears of substantial rate increases abound.

“The governor is willing to put the law off to the side in order to appease fossil-fuel interests, big private business interests … and for New York families to foot the bill for that,” said Kim Fraczek, the executive director of Sane Energy, a nonprofit organization that is advocating for the replacement of gas infrastructure with renewable energy. “Our costs will only increase, and that’s for ratepayers and for businesses.”

A report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, an energy-research think tank, estimated that the pipeline would cost $1.25 billion — almost $200 million more than what National Grid had said — due to construction inflation. Even if National Grid’s figures are correct, ratepayers would suffer a substantial monthly increase.

National Grid has predicted that the pipeline will cost ratepayers an additional $7.50 per month if approved. But it has also argued that the pipeline could help lower electricity bills by reducing the price of natural gas, which powers many of the state’s electricity plants.

Hochul is also experiencing pressure from the other side of the aisle. Energy Secretary Wright recently criticized the state’s Climate Act, which requires the state to have a net-zero-emissions electricity grid by 2040, calling it “totally nuts.”

“The longer and more aggressively [net-zero] is pursued, the more you elevate your energy prices and impoverish your citizens,” Wright told journalists at the press conference in Long Island earlier this month. “Let’s build more energy infrastructure to drive down the cost of energy here in New York state, across New England, and across our country.”

Whether the Climate Act drives the state’s high energy prices remains a subject of debate. A recent Public Service Commission report found that cost recovery for Climate Act measures accounted for anywhere from 5% to 9.5% of a residential customer’s monthly electric bill — but consistently 2% or less of their gas bill — in 2024.

Another factor contributing to higher rates has been large-scale improvements in gas infrastructure. Last year, residents in downstate New York experienced rate hikes when National Grid began a $5 billion system upgrade, which included replacing “leak-prone” pipes across the region.

Australia has put itself on a realistic path to achieving what climate activists around the world have long dreamed of: running its power grid entirely on renewable energy.

The Australian Energy Market Operator oversees the nation’s power markets. Chief among them, the National Electricity Market serves about 90% of customers, minus remote areas and the west coast. At its peak, the system uses 38 gigawatts of power — more than New York state’s peak consumption. Over the last five years, AEMO has rigorously studied how the country, whose coal fleet is aging and which banned nuclear energy decades ago, can run this grid on renewables alone.

“This is not a climate-zealot kind of approach,” AEMO CEO Daniel Westerman told Canary Media. “Our old coal-fired power stations are breaking down; they’re retiring,” he said. “They’re getting replaced by the least-cost energy, which is renewable energy, backed with storage, connected in with transmission. We’ll have a bit of gas there for the winter doldrums. That is just what’s happening.”

Australia’s efforts could offer a proof of concept for how a nation with a bustling, modern economy can rapidly shift its electricity from fossil fuels — mostly coal with some gas — to wind, solar, storage, and other renewable sources like hydropower.

“There’s nothing impossible about 100% renewable supply,” said Jesse Jenkins, a Princeton University professor who has studied net-zero pathways for the U.S. “Australia has a better chance of this than almost anywhere.”

So far, renewables have surged to about 35% of annual electricity production, while coal still leads with 46%, according to the International Energy Agency.

Because this transition is primarily driven by market forces, rather than a legislative or regulatory requirement, Westerman couldn’t say for sure when Australia will hit the 100% mark. He does expect 90% of Australia’s coal generation will be gone by 2035, and the rest could shutter later that decade.

The more pressing milestone, though, will be the country’s first day with no coal generation on the system, which could happen far sooner due to some combination of competitive forces and mechanical trouble at the aging plants. It’s a landmark Westerman has experienced before: He operated the U.K. electricity network in 2017 when it ran without coal for the first day since the Industrial Revolution. The last British coal plant shut down seven years later, in 2024.

AEMO has developed a clear sense of what is needed to keep the lights on whenever coal power flickers out, he said. It’s a matter of getting “kit installed in the ground,” especially the unsexy machinery that can maintain a stable grid in the absence of big fossil-fuel-powered generators.

“It’s now a physical problem rather than an intellectual challenge, a ‘no one knows how to do this’ challenge,” Westerman said. “We can deal with that.”

Australia’s renewables outlook is strong for a few key reasons.

For one, it enjoys distinct geographical advantages, Jenkins noted: It spans a sunny, windy landmass the size of the contiguous United States, but with just 27 million people to provide for. (The U.S. has nearly 13 times more.)

It also has policy advantages. Australia has a national market governing the power sector, which allows technologies to proliferate faster than in places with patchwork regulations (like the U.S.) or strong incumbent monopoly utilities (also like the U.S.). Furthermore, Australia has avoided U.S.-style clean-energy trade protectionism, so cheap Chinese imports are plentiful.

Last month, the National Electricity Market topped out at more than 77% renewable generation for a half-hour period, Westerman said. Grid constraints kept that number from being even higher. The state of South Australia regularly generates more electricity from renewables than it consumes, shipping the excess to neighbors.

Australia doesn’t just excel at big renewables and big batteries. Four million homes produce rooftop solar; a few weeks ago, those households temporarily supplied 55% of demand on the National Electricity Market, Westerman said.

“Australians have an absolute love affair with rooftop solar,” he said. “We have the highest rooftop PV penetration in the world, and it’s one of the driving forces of our energy transition.”

Westerman flagged one big technical obstacle to reaching 100% renewables, and it’s not what many people expect.

The key hurdle to unlock a completely renewable system is to build up “rotating machines on the grid that don’t necessarily produce power,” Westerman said.

The physical spinning mass of the old coal plants’ generators delivered “essential system services” beyond just the kilowatt-hours. These services aren’t known to many people beyond grid engineers, but they go by names like voltage support, frequency regulation, synchronous inertia, and reactive power. Westerman describes them as “shock absorbers … to withstand the bumps and disturbances that we get all the time.”

“The consequence of not having system security is Spain and Portugal,” he said, referring to the nationwide blackouts this spring that have been traced to failure to control voltage levels.

If the coal plants are headed for extinction, something else needs to take on these responsibilities. Batteries can replicate some services. But Westerman worries about a service called fault current, which is necessary to operate the grid-scale version of fuses or breakers that protect equipment from issues like short circuits.

One way to do this is by building devices called synchronous condensers, which include a rotating hunk of metal that can spin without fossil-fuel combustion. But constructing new single-purpose infrastructure is expensive, especially when the energy-only markets don’t currently reward this grid service on its own.

Westerman has been talking up another option largely absent from decarbonization discourse in the U.S.: install a clutch on existing gas plants, on the shaft between the fuel-burning turbine and the spinning generator. The clutch isolates the generator, so it can keep spinning with a relatively minor jolt of electricity and without burning fossil fuels. This approach also keeps the gas plant around to produce power on what Westerman described as “cold, dark, and still” days, when the renewable fleet falls short. Such plants could eventually switch to biofuels or clean hydrogen instead of fossil gas.

“[The clutch] is like 1950s technology — it’s really boring,” Westerman said (“boring,” for grid operators, is the highest form of praise). “The marginal cost of putting this in is like nothing compared to the cost of the plant.”

A company called SSS has built these clutches for decades. One is nearly operational in the state of Queensland at the Townsville gas-fired plant, which Siemens Energy is converting into what it calls a “hybrid rotating grid stabilizer.” Siemens says this project is the world’s first such conversion of a gas turbine of this size.

That particular retrofit took about 18 months and involved some relocating of auxiliary components at Townsville to make room for the new clutch. So it’s not instantaneous, but far easier than building a new synchronous condenser from scratch, and about half the cost, per Siemens.

Some novel long-duration storage techniques also provide their own spinning mass. Canadian startup Hydrostor expects to break ground early next year on a fully permitted and contracted project in Broken Hill, a city deep in the Outback of New South Wales.

Broken Hill lent its name to BHP, which started there as a silver mine in 1885 and has grown to one of the largest global mining companies. More recently, the desert landscape played host to the postapocalyptic car chases of Mad Max 2. Now, roughly 18,000 people live there, at the end of one long line connecting to the broader grid.

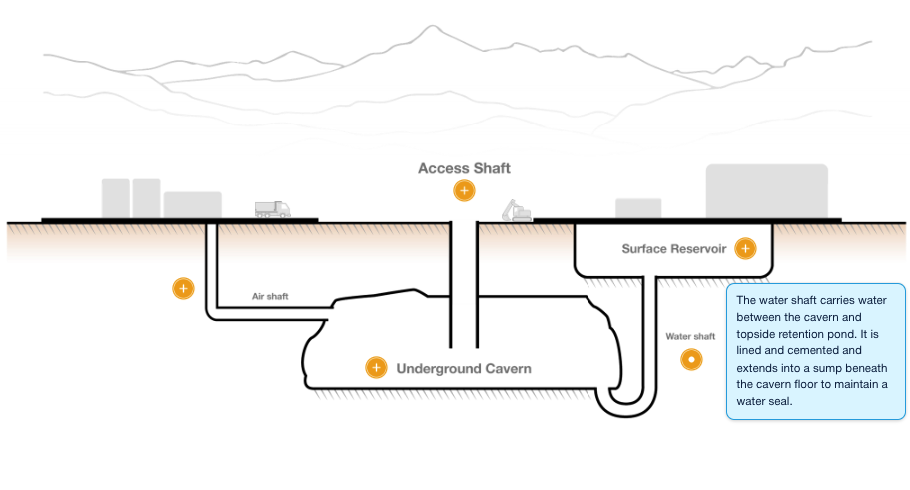

Hydrostor will shore up local power by excavating an underground cavity and compressing air into it; releasing the compressed air turns a turbine to regenerate up to 200 megawatts for up to eight hours, serving the community if the grid connection goes down and otherwise shipping clean power to the broader grid.

But unlike batteries, Hydrostor’s technology uses old-school generators, and its compressors contribute additional spinning metal.

“We have a clutch spec’d in for New South Wales, because they need the inertia,” Hydrostor CEO Jon Norman said. “It’s so simple; it’s like the same clutches on your standard car.”

Transmission grid operator Transgrid ran a competitive process to determine the best way to provide system security to Broken Hill in the event it had to operate apart from the grid, Norman said. That analysis chose Hydrostor’s bid to simply insert a clutch when it installs its machinery.

The project still needs to get built, but if up-and-coming clean storage technologies could step in to provide that grid security, it wouldn’t all have to come from ghostly gas plants lingering on the system.

“It’s a different feeling [in Australia] — there’s a can do, go get ‘em, ‘put me in coach’ attitude,” said Audrey Zibelman, the American grid expert who ran AEMO before Westerman. “When you’re determined to say how best to go about this, as opposed to why it’s hard or why it doesn’t work, the solutions appear.”

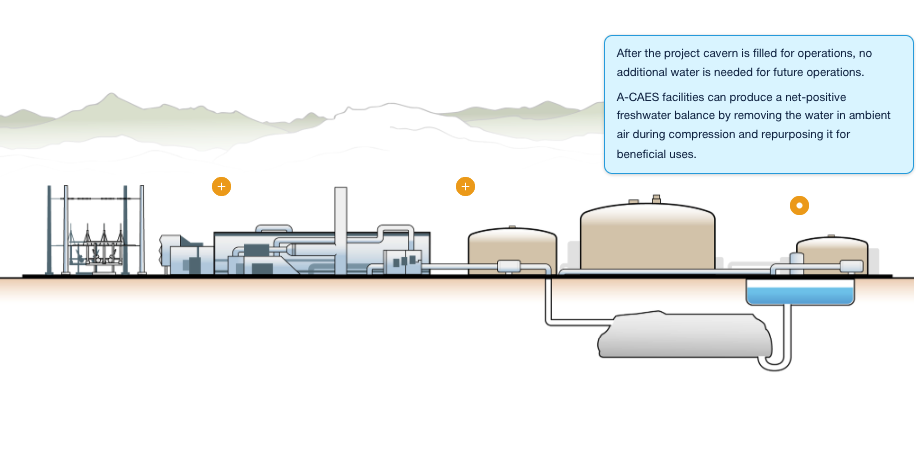

What is A-CAES?

Advanced compressed air energy storage (A-CAES) is a technology that stores energy by compressing air and later releasing it to generate electricity. It is an enhanced form of traditional compressed air energy storage (CAES), which has been in use in California and other parts of the world for decades. Hydrostor’s key advancement is that A-CAES captures and stores the heat generated during the compression phase and uses it to reheat the air during expansion, which significantly improves efficiency while eliminating the use of fossil fuels for daily operations. This patented technology makes it a much more environmentally friendly and cost-effective method for large-scale, long-duration energy storage.

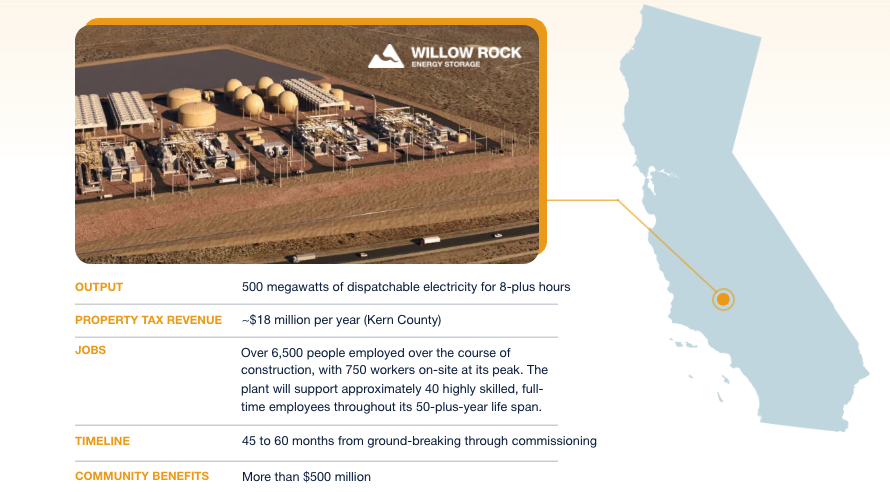

Take a look at how Hydrostor’s Willow Rock Energy Storage Center (WRESC) project in Kern County, California, is contributing to the state’s energy priorities:

From drawing board to full operation: a phased approach

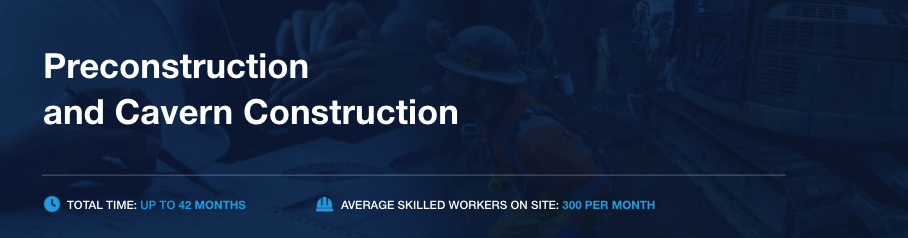

Construction of the Willow Rock project is anticipated to take 60 months from the time the project breaks ground until it goes online. The construction work will take place in six phases:

Preconstruction

Before any physical work can begin on a project of this scale, Hydrostor does substantial preliminary work to ensure there are minimal impacts to the surrounding communities and environment. Preconstruction assessments completed for the Willow Rock Energy Storage Center evaluated potential impacts on air quality, cultural resources, geologic conditions, soil health, water quality, and other factors and included recommendations on how to mitigate those impacts. An extensive permitting process will involve consulting with the local community, state agencies, and federal agencies before construction begins. A-CAES facilities have a smaller physical and environmental footprint than other energy infrastructure, using five to 20 times less water than pumped hydro and more than 10 times less land than solar for an equivalent amount of energy.

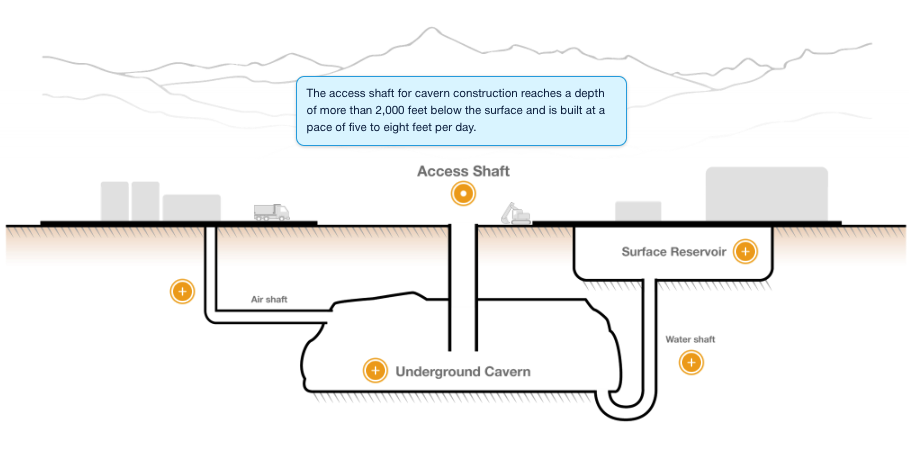

Cavern Construction

The first parts of an A-CAES facility to be built are the underground cavern and its associated air, water, and construction shafts. The storage cavern is constructed in bedrock approximately 2,000 to 2,500 feet belowground. This subsurface work is the most time-consuming portion of construction, taking roughly three years.

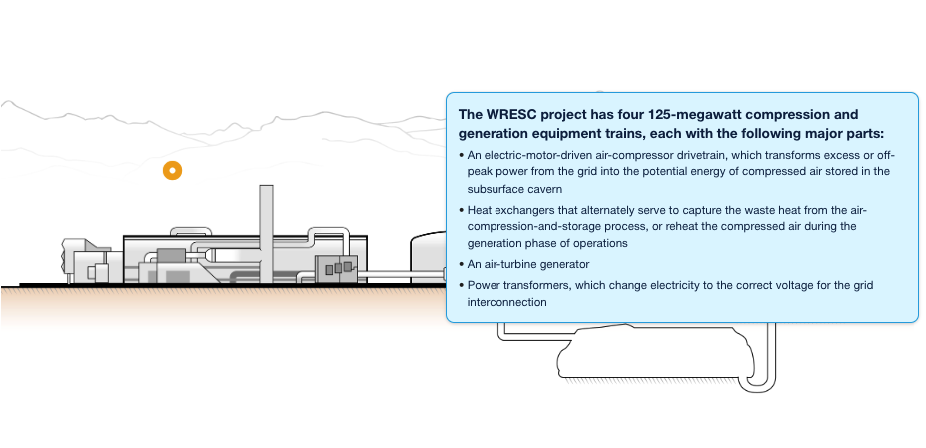

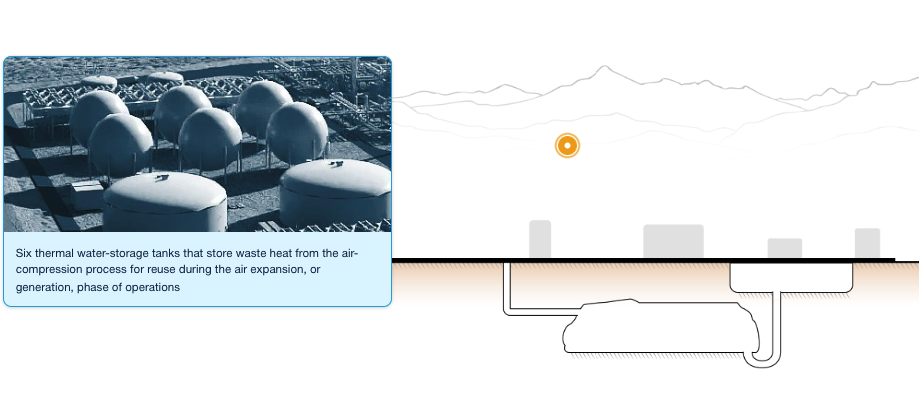

Topside Construction

Once the subsurface construction is underway, topside construction begins. This phase includes installing turbines, thermal storage tanks, and the rest of the facility’s aboveground equipment in addition to constructing the transmission line.

Transmission

The Willow Rock Energy Storage Center is located near the project’s transmission interconnection point, the SCE Whirlwind Substation, thereby reducing the time, cost, and complexity of building the transmission infrastructure.

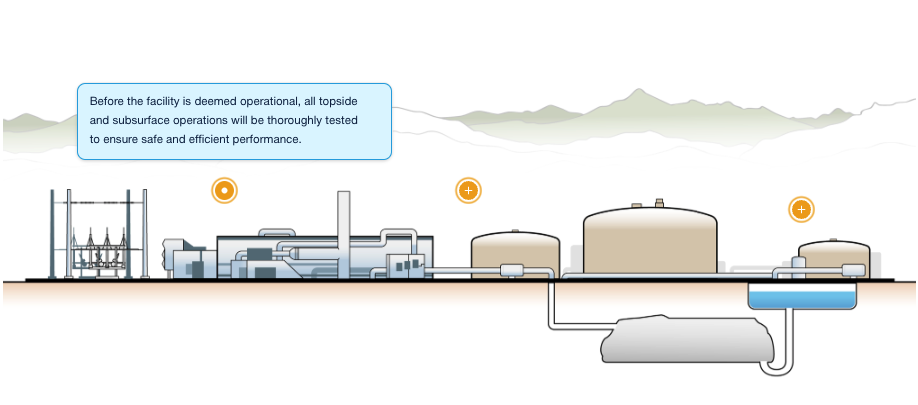

Once construction is complete, all project equipment will be rigorously tested for safety and efficiency before Willow Rock officially begins providing reliable power to millions of Californians.

Willow Rock’s 50-Plus Year Commercial Life Span

Once operational, A-CAES facilities like Willow Rock — unlike many other energy storage technologies — will operate with zero efficiency loss over its expected commercial life span of 50 years or more. This means Hydrostor’s work in host communities—and the jobs it creates to operate each facility—are long-term commitments that provide lasting local and regional benefits.

A-CAES projects' flexible siting, energy density, environmental attributes, and community benefits make them an excellent fit for many regions across the U.S. Learn more about Hydrostor's growing project pipeline here.

California has labored for years to build enough clean energy to wean itself off fossil fuels. Now the effort is paying off in an undeniable way.

President Donald Trump’s Department of Energy might tweet that solar plants are “essentially worthless when it is dark outside.” But in California, batteries are proving the opposite, by shifting ever more solar into evening and nighttime hours. Consequently, solar generation hit new highs in the first half of the year, and fossil-gas generation has fallen rapidly in turn.

From January to July, as noted by Reuters, solar generation delivered 39% of the state’s generation, a record level, while fossil fuels provided just 26%, a new low since the dawn of modern gas power. In April, a temperate shoulder month, gas generated less than 20%. For context, across all of last year, solar provided 32% of California’s power — the highest rate of any U.S. state — nearly unseating gas as the largest source of power.

These trends have resulted in numerous clean energy records this summer. In the California Independent System Operator’s grid, which serves most of the state, solar delivered a record 21.7 gigawatts just past noon on July 30. Two days later, at 7:30 p.m., the battery fleet set its own record, nearing 11 gigawatts of instantaneous discharge for the very first time (it has since beat that record).

California’s electricity supply increasingly diverges from the nation’s. Gas has predominated since 2016, and now accounts for more than 40% of U.S. generation; coal, meanwhile, has fallen to around 16%. The carbon-free cohort includes nuclear and renewables at around 20% each. Solar, including rooftop systems, provided about 7% of U.S. electricity last year, according to Ember.

Initially, California’s billions of dollars in solar subsidies and suite of supporting policies couldn’t overcome the state’s gas dependency. The solar systems cranked out excess power through the sunny hours, much of which got curtailed for lack of simultaneous demand, then California turned to fossil fuels to keep the lights on at night. That addiction at times overpowered the state’s environmental ethos: California even opted in 2020 to waive enforcement of a regulation protecting marine life because it would have shuttered a number of coastal gas plants that the grid wasn’t ready to lose, despite having a decade to prepare for the rule.

Such desperation gave temporary succor to solar skeptics and gas boosters. But when an energy system starts to change, snapshots in time are less instructive than the trend lines. And California’s trend lines have been pointing in one direction.

While the state hasn’t been building new gas generation, it has connected gigawatts of new solar and batteries each year. These resources are nearly free to operate once built, while gas plant owners have to buy fuel to combust and keep complex machinery in fine working order. And the price of gas has been going up, amid greater demand both at home (due to data center expansion) and abroad (with liquefied exports going to the highest bidder). Now California’s gas plants have more competition in the peak hours from cheaper, cleaner resources; they’re getting squeezed toward fewer hours of intense demand.

But it would be a mistake to think that these trends stop at the Sierra Nevada. Indeed, these patterns are playing out nationally: Very little new gas capacity is getting built, quite a lot of solar and batteries are, and gas prices are going up.

Some regions allow developers to respond nimbly to these trends, namely Texas, which indeed has leapt ahead of California in its pace of solar and storage installations. Other regions obstruct such dynamism and face the consequences, like the mid-Atlantic wholesale markets run by PJM, where skyrocketing capacity auctions are pushing costs to crisis levels.

California’s grid overhaul has been a long time coming, and one lesson here is that big changes — like redesigning the energy system for the world’s fourth largest economy — take time. But other states won’t have to wait as long: They can tap into a mature supply chain that scaled up thanks to California and other early adopters, plus the industrial expertise to design and manage large solar construction efforts and the financing options de-risked by years of data from earlier projects.

The federal government is trying to stymie renewables however it can. But California is demonstrating the rewards for getting solar to escape velocity, and that momentum is set to carry forward in the coming years.

About 30 miles off the coast of Virginia Beach, Virginia, workers have been building America’s largest offshore wind farm at a breakneck pace. The project will start feeding power to the grid by March — the most definitive start date provided by its developer yet.

“First power will occur in Q1 of next year,” Dominion Energy spokesperson Jeremy Slayton told Canary Media. “And we are still on schedule to complete by late 2026.”

In an August earnings call, Dominion Energy CEO Robert Blue provided a vague window of “early 2026” when asked when the 2.6-gigawatt Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind (CVOW) project would start generating renewable power for the energy-hungry state.

As of the end of September, Dominion had installed all 176 turbine foundations — “a big, important milestone,” per Slayton. That accomplishment involved pile-driving 98 foundations into the soft seabed during the five-month stretch when such work is permitted. Good weather helped the work move along quickly, as did the Atlantic Ocean’s unusually quiet hurricane season.

Speed is key when building wind projects under the eye of a president who has called turbines “ugly” and “terrible for tourism” — and who has followed up with attempts to dismantle the industry.

Had CVOW not finished foundation installation by the end of this month, turbine construction would have been delayed until next spring. Federal permitting restricts pile-driving to a May-through-October window to protect migrating North Atlantic right whales. Such a delay would have made CVOW more vulnerable to the wrath of the Trump administration, which has already issued stop-work orders to two offshore wind farms under construction.

But Slayton said the threat of President Donald Trump’s interference doesn’t concern him. CVOW is, after all, one of only two in-progress offshore wind projects that hasn’t been directly attacked by the president.

“Our project has enjoyed bipartisan support from the beginning,” he said, pointing to backing from some of the state’s leading Republicans, including Gov. Glenn Youngkin and U.S. Rep. Jen Kiggans.

Kiggans, who represents the politically moderate Virginia Beach area, brought her concerns about Trump’s escalating war on wind to the House floor last month, when Congress returned from recess. She called CVOW “important to Virginia,” and House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-Louisiana) later told reporters that he relayed Kiggans’ message directly to Trump.

“I understand the priority for Virginians and we want to do right by them, so we’ll see,” Johnson told Politico’s E&E News, in a comment that broke from an anti–offshore wind narrative that’s taken root among many of his fellow House Republicans.

The project is crucial for helping the state meet a deluge of new electricity demand, as Virginia is at the center of the nationwide boom in data-center construction. CVOW will provide a huge amount of carbon-free power to the state and Dominion, its largest utility — helping both keep pace with rising demand without having to burn more polluting fossil fuels.

Kiggans also tied the success of CVOW to the needs of Virginia’s military installations.

“I always speak about that project in light of the national security benefit and that benefit to Naval Air Station Oceana,” Kiggans said last month in an interview with WAVY, a Virginia news station, noting that a partnership with Dominion is “giving Naval Air Station Oceana a $500 million power grid upgrade.”

Dominion has already spent $6 billion on the monumental effort to build CVOW, which has been 12 years in the making. Almost $1 billion of that investment has flowed to the local economy, creating 802 full- and part-time jobs in the state’s Hampton Roads region, according to G.T. Hollett, Dominion Energy’s director of offshore wind.

CVOW’s benefits are being felt nationwide too.

“The project has already created 2,000 direct and indirect American jobs and generated $2 billion in economic activity, strengthening the nation’s manufacturing supply chains and our regional economy,” said Katharine Kollins, president of Southeastern Wind Coalition.

Now Dominion will turn to the final phase of construction: turbine installation. The work is made possible by Charybdis — the first U.S.-built, Jones Act–compliant wind-turbine installation vessel — which arrived in Virginia’s Portsmouth Marine Terminal last month.

“When Charybdis is loaded up, it will have all the components to install four turbines with each trip,” said Slayton, who noted that the pace of the build is well timed given Virginia’s data-center boom. The state is facing “record growth and energy demand … maybe you’ve heard.”

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the week” column.

Renewable energy just notched a major milestone.

Worldwide, renewables produced more electricity than coal across the first half of this year — a first, according to clean-energy think tank Ember.

The global revolution in solar deployment made the milestone possible. The energy source more than doubled its share of global electricity generation over the last four years alone, rising from 3.8% in 2021 to 8.8% in the first half of 2025. Wind power also grew modestly during the first half of the year.

Taken together, the two clean-energy sources increased fast enough to not only meet all new electricity demand in the first six months of 2025, but to displace a bit of fossil fuel use as well.

Despite the progress, coal remains the single largest source of electricity in the world. No renewable-energy source on its own — be it wind, solar, hydro, or bioenergy — measures up to coal. And although renewable energy on the whole has now surpassed coal, it’s not like coal generation is plummeting. Power plants still plowed through more coal in the first half of this year than they did in the first half of 2021.

But coal power is stagnant. Meanwhile, renewables, and solar in particular, are ascendant. This latest milestone is worth celebrating not because fossil fuel use has been dealt a fatal blow, but because it’s a clear illustration of the trajectory each energy source is on.

For the world to truly reorient itself around energy sources that don’t bake the planet and spew toxic fumes into the air, those trends must not only continue but accelerate. Coal — and eventually gas — will need to decline as assuredly as renewables soar. Let’s call this a step in that direction.