American factories use lots of hot water and steam to produce everyday goods like milk, cereal, beer, toilet paper, and bleach. Most facilities burn fossil fuels to get that heat, emitting huge amounts of planet-warming pollution in the process.

Switching to electricity could significantly and immediately slash those emissions in many places, according to a new report by The 2035 Initiative at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Electric versions of industrial boilers, ovens, and dryers are already available, and newer models promise to boost factories’ efficiency and curb energy costs even further.

“We can make progress today with the technologies we have,” said Leah Stokes, an associate professor of environmental politics at UC Santa Barbara and one of the principal researchers for the report.

But electrifying factories is a far more complex undertaking than, say, trading a gasoline-fueled car for a battery-powered vehicle. The process involves making many head-scratching calculations and engineering choices, which is partly why companies have been slow to adopt electrified equipment. Stokes said the report aims to demystify some of those decisions so that U.S. manufacturers can start tackling their heat-related emissions.

“We wanted to answer this question [of] where is it most technologically and economically feasible to electrify industrial process heat today?” she said during a Dec. 16 webinar. The study also drives home the need to rapidly build more clean energy to power all that new demand.

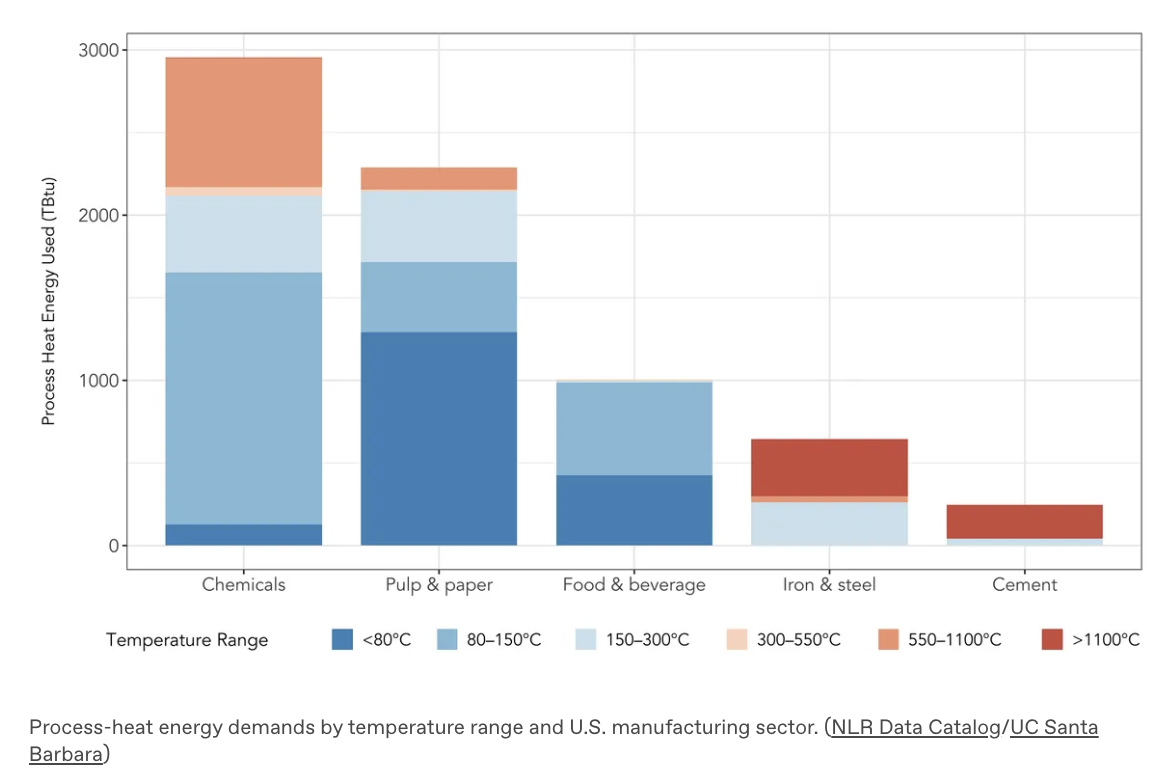

Researchers simulated what it would look like to electrify nearly 800 large industrial plants within three sectors: food and beverage, chemicals, and pulp and paper manufacturing. These facilities use relatively low- and medium-temperature process heat — unlike scorching cement kilns or steel mills — and together account for about 40% of CO2 emissions from the U.S. industrial sector.

The UC Santa Barbara team modeled four scenarios for electrifying each of these plants, beginning with “drop-in electrification” — using electrode boilers and electric ovens and dryers — and progressively expanding efforts to include major energy-efficiency upgrades and advanced technologies, like high-temperature heat pumps from the startups AtmosZero and Skyven.

At the most ambitious level, electrifying these factories could slash the country’s emissions by 1.3 billion metric tons of CO2 equivalent by 2050, while also providing $475 billion in public health benefits by improving air quality, researchers found. The figures assume the U.S. electric grid will be running almost entirely on clean energy by mid-century, up from 40% today.

“This one space actually can contribute an outsize share of the global [climate] mitigation we need to keep our global temperature rise in check,” said Eric Masanet, a sustainability science professor at UC Santa Barbara who led the study with Stokes.

In certain cases, it can cost manufacturers about the same amount of money to get heat from electric systems rather than gas-fired ones, he said. That includes processes that use less intensive heat, like ethanol and plastics production, since heat pumps work more efficiently at lower temperatures. It’s also true for factories located in places where fossil gas is relatively expensive. In Delaware, New York, and Washington state, for example, companies enjoy a more favorable “spark gap” — the difference between electricity and gas utility costs for the same unit of energy delivered.

Just as cost varies by facility, so does the potential for emissions reductions. The largest CO2 savings are in states with low-carbon grids, like Washington, California, and Vermont. In places with dirtier grids, switching to electricity can actually increase emissions in the near term if utilities meet that demand with gas- and coal-fired power plants. But even in those areas, researchers expect that electric equipment installed today will still cut pollution over time as the grid gets cleaner.

For that to happen, factories will need a lot more wind, solar, geothermal, and other carbon-free sources to come online. Electrifying the processes included in the study could require 158 to 301 terawatt-hours of additional power, or about 16% to 30% of the electricity currently consumed by industry. That new load would add to the soaring demand that’s already coming from data centers and electrified homes and vehicles.

“If we want to bring the type of electricity to the industrial sector that it’s going to need … we’re going to need to improve the grid,” Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) said during the webinar, adding that streamlining the federal permitting process would hasten the build-out of new transmission and clean energy projects.

The UC Santa Barbara team outlined other policies that could accelerate industrial decarbonization, particularly for the facilities where electrification is more expensive than burning fossil fuels. A 30% federal investment tax credit or state-level grants would offset the up-front costs of investment in new equipment. A “clean heat” production tax credit would lower operating costs, as would reducing industrial electricity rates.

Stokes noted that, even without such incentives, cleaning up manufacturing would take a minimal toll on consumers’ wallets. Take breweries, which use heat for mashing, boiling, and fermenting ingredients and sterilizing containers. “Our modeling shows that even if electrification doubles the cost of energy as an input to beer production, it’s 1 cent per beer,” she said.

“This is something that we can do, and it’s super important,” she added.