Technological advances are expanding where geothermal electricity canbe produced - making it a cost-competitive, secure alternative to gas forindustry and other power-intensive users.

This analysis examines how advances in geothermal technology are changingthe prospects for geothermal electricity in Europe: its resource potential, costsand deployment trends. The report considers how policy conditions shape thepace of new projects and geothermal’s role in evolving electricity systems.

Modern geothermal is pushing the energy transition to new depths, opening up clean power resources that were long considered out of reach and too expensive. But today, geothermal electricity can be cheaper than gas. It’s also cleaner and reduces Europe’s reliance on fossil imports. The challenge for Europe is no longer whether the resource exists, but whether technological progress is matched by policies that enable scale and reduce early-stage risk.

Tatiana Mindekova

Policy Advisor, Ember

The EU’s Geothermal Action Plan must include clear commitments to liberate Europe’s power sector from costly fossil fuel dependency. The potential to replace 42% of coal and gas generation with geothermal is simply too significant to ignore. Ember’s report highlights the crucial role geothermal plays in delivering affordable energy, security, and competitiveness. With Energy Ministers and the European Parliament calling for concrete action, it is now up to the European Commission to remove the barriers to mass geothermal deployment.

Sanjeev Kumar

Policy Director, European Geothermal Energy Council

Europe has far more geothermal potential than is commonly accounted for. Next-generation geothermal strengthens Europe’s heat sector and extends its impact to clean, secure, and reliable electricity across much of the continent. Continued investment in innovation and supportive policy can turn this resource into a major pillar of EU’s clean firm power system.

Jenna Hill

Superhot Rock Geothermal Innovation Manager, Clean Air Task Force

Technologies allow geothermal to deliver scalable and clean power across much of Europe. Not just in volcanic regions. Across the European Union, around 43 GW of enhanced geothermal capacity could be developed at costs below 100 €/MWh, placing geothermal firmly within reach as a competitive source of firm, low-carbon electricity. Yet much of this technological progress has gone largely unnoticed and geothermal is still widely viewed as unavailable across much of Europe.

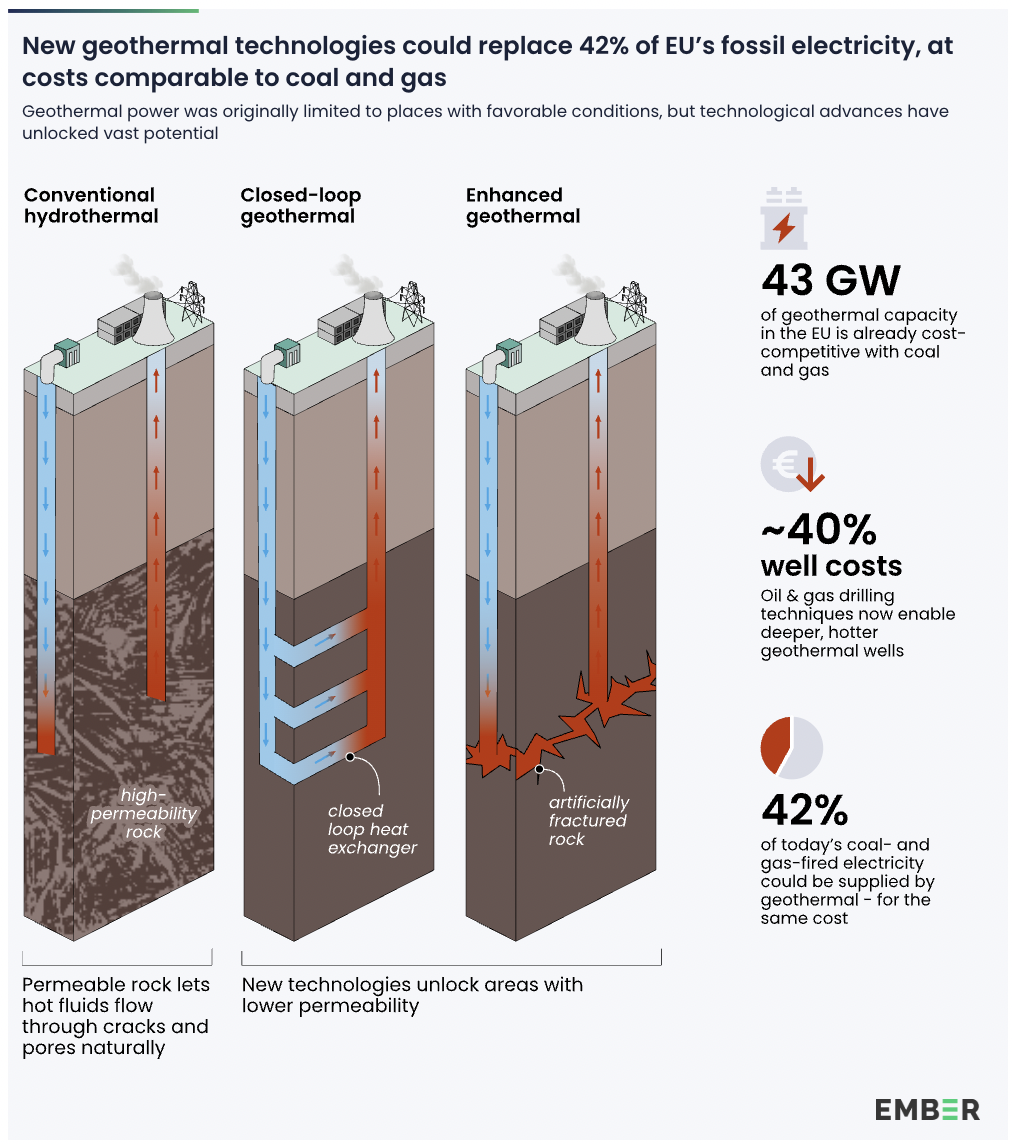

Geothermal power generation was long considered viable only in volcanic regions such as Iceland or Indonesia. Conventional geothermal relied on underground rock formations that were both hot and naturally permeable, allowing water already present at depth to circulate and transport heat. These rare conditions confined large-scale deployment to a limited number of regions worldwide. As a result, geothermal energy remained a niche contributor to global electricity generation (99TWh or less than 0,5% in 2024) despite its dispatchable nature and low emissions profile.

During the last decade, progress in geothermal technologies – often referred to as ‘next generation geothermal’ – has removed the need for naturally occurring permeability, meaning the presence of open pores in rock that allow fluids to flow. New approaches can now create or enhance these flow pathways artificially. Combined with more cost-effective deep drilling and advances in power-conversion systems that enable electricity generation at lower temperatures, significantly expanding the range of geological settings suitable for geothermal power generation. As a result, geothermal deployment is expected to accelerate rapidly: by 2030, nearly 1.5 GW of new capacity is expected to come online each year globally, three times the level added in 2024. At the global level, geothermal could meet up to 15% of the growth in electricity demand by 2050.

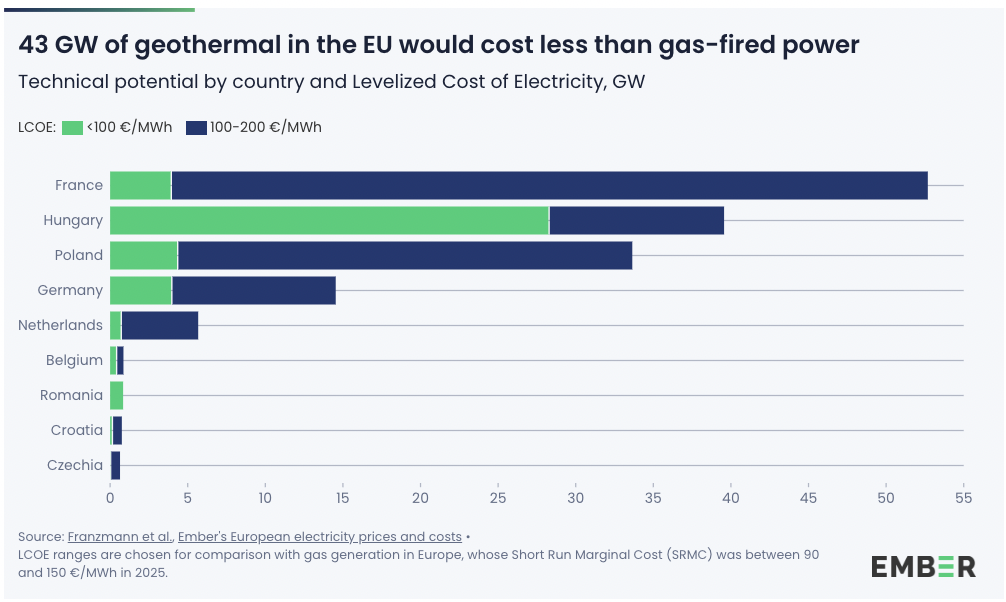

Recent advances in geothermal systems mean that geothermal electricity can now be produced at prices comparable to coal- and gas-fired generation, even outside traditionally high-temperature zones. Focusing on projects with estimated costs below 100 €/MWh – consistent with prices (short-run marginal costs) set by coal- and gas-fired generation in European power markets – and accounting for reservoir behaviour, plant performance and drilling depth, the techno-economic potential for geothermal power in continental Europe reaches around 50 GW.

Under this threshold, Hungary accounts for the largest share, with around 28 GW, followed by Türkiye with almost 6 GW and Poland, Germany, and France with around 4 GW each.

For EU member states alone, this corresponds to around 43 GW of deployable geothermal capacity, capable of generating approximately 301.3 TWh of electricity per year given geothermal’s high capacity factor. This is equivalent to around 42% of all coal- and gas-fired electricity generation in the EU in 2025.

At these cost levels, geothermal power would be competitive with the prices set by coal- and gas-fired generation in European power markets, where short-run marginal cost has been oscillating between 90 and 150 €/MWh in 2025. Not only can geothermal power capacity be developed at low prices, but as a technology with no fuel costs, it brings the additional benefit of being insulated from fuel price volatility and exposure to rising carbon costs, strengthening its role as a stable source of firm, low-carbon electricity over time.

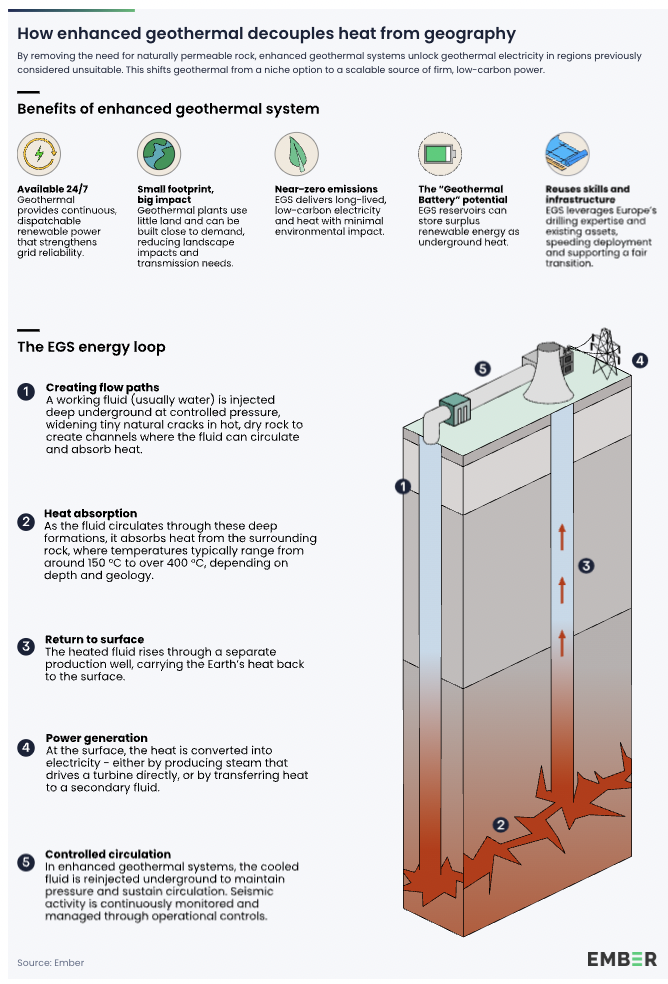

The potential of geothermal energy for electricity generation is expanded by changes in the design of geothermal projects. The term next-generation geothermal encompasses several design improvements to geothermal systems. These include accessing underground heat without relying on natural heat pathways, using artificial heat carriers, or creating closed-loop systems. A type of next generation technology most commonly deployed is Enhanced Geothermal System(s) (EGS). EGS can engineer reservoirs in deep, hot rock where natural water or permeability is low or absent, unlocking potential beyond traditional hotspots.

In EGS projects, wells are drilled into hot rock and permeability is created or enhanced to allow a working fluid to circulate and extract heat. The heated fluid is brought to the surface through these artificial cracks to generate electricity. Experience from recent projects shows that seismic risks resulting from such drilling can be managed through monitoring and operational controls.

Geothermal reservoirs can be operated flexibly to absorb surplus wind or solar electricity indirectly, primarily through increased pumping and injection, and later the release of stored thermal and pressure energy to generate additional power. By varying injection and production rates, operators can “charge” the reservoir and later “discharge” it to increase output during high-value periods. Simulations show that heat can be stored for several days with efficiencies comparable to lithium-ion batteries. Because this capability is built into the same infrastructure used for power generation, it adds flexibility at low additional cost.

In addition, geothermal operations can generate value beyond electricity through the recovery of critical minerals from produced brines. Lithium concentrations in geothermal brines typically range in levels that can be commercially viable using new direct lithium extraction techniques. These methods recover up to 95 % of the lithium contained in the brine, compared with roughly 60 % from hard-rock mining, while using far less water and generating almost no carbon emissions.

Geothermal electricity is already cost-competitive with fossil fuels in Europe. The levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) of geothermal power – the cost of producing one unit of electricity based on the construction and operating costs of a power plant over its lifetime – is already low, at around USD 60 /MWh, placing it below most fossil-fuel generation (~ USD 100 / MWh in Europe). This reflects geothermal’s high capacity factors and the fact that existing projects have largely been developed in favourable geological conditions using conventional designs, with average depth of well between 1 to 3km.

Drilling and reservoir development remain the dominant drivers of capital expenditure, making early-stage investment risk a central barrier for deeper and more complex projects. Over the past decade, however, drilling and reservoir-engineering techniques adapted from the oil and gas sector have reduced well costs by roughly 40%, enabling economically viable access to hotter and deeper resources. As these capabilities scale, they expand the share of geothermal resources that can be developed at competitive cost.

Geothermal electricity potential increases as drilling reaches deeper, higher-temperature resources, but the depth at which suitable temperatures occur varies significantly across countries. In the European Union, assessments limited to resources accessible at depths of up to 2,000 m — where sufficiently high temperatures are available only in a subset of locations — yield a relatively constrained level of technical potential (139GW). As access extends to deeper and hotter resources, geothermal conditions become more widely available across the EU. Extending the depth range to 5,000 m increases the estimated potential by more than 50 times, while access to resources down to 7,000 m results in an increase of roughly 180 times.

In the EU, projects that take advantage of the newly accessible resources are already under construction, reaching depths beyond 4000m. Moreover, there are existing projects that have already reached depths close to 5000m, demonstrating that utilising geothermal resources at these depths commercially is already achievable with today’s technology.

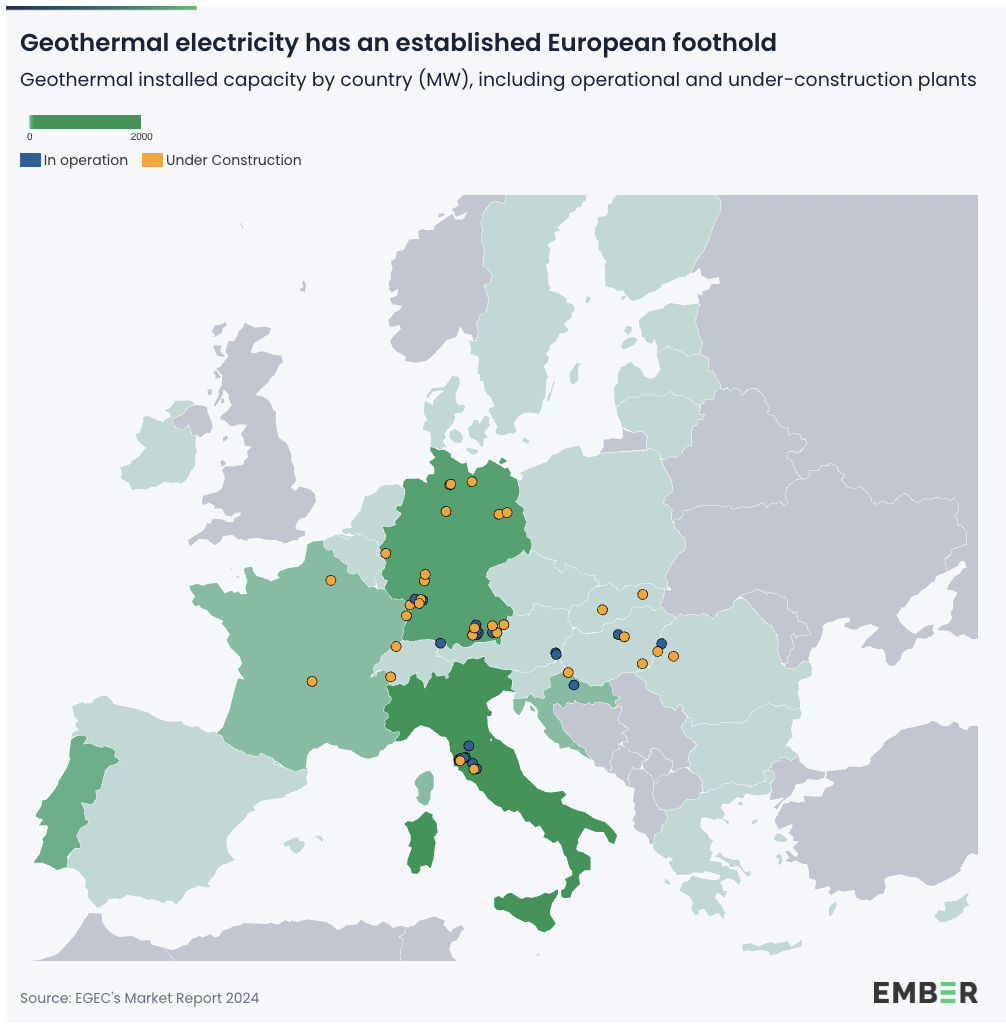

Europe played a central role in the development of geothermal energy. The world’s first geothermal electricity was produced in Italy, in 1904, and as of 2024, Europe had 147 geothermal power plants in operation. Of these, 21 have been producing electricity for more than 25 years, underscoring the long-term value of geothermal investments. In 2024, these plants produced around 20 TWh of electricity from just over 3.5 GW of installed capacity (roughly one-fifth of global geothermal capacity).

Geothermal generation in Europe remains highly concentrated. The majority of its output came from Türkiye, Italy and Iceland, which together accounted for nearly all geothermal generation in the region. Beyond these established markets, activity is spreading: several countries already produce geothermal electricity, including Croatia, France, Germany, Hungary, Austria and Portugal, while new capacity is under development in Belgium, Slovakia and Greece. Across Europe, around 50 geothermal power plants are currently moving through development, from early exploration to grid connection, with Germany leading in active projects.

Pilot EGS projects launched in France, Germany and Switzerland in the 2000s demonstrated that hot, impermeable rock could be converted into productive reservoirs. More than 100 EGS projects have now been carried out worldwide, with Europe accounting for the largest share (42), followed by the United States (33), Asia (15), and Oceania (12). More recently, EGS projects have moved from commercial demonstration to full scale development. Advanced geothermal systems are also progressing, with Europe’s first closed-loop project now operating as a grid-connected power plant in Germany.

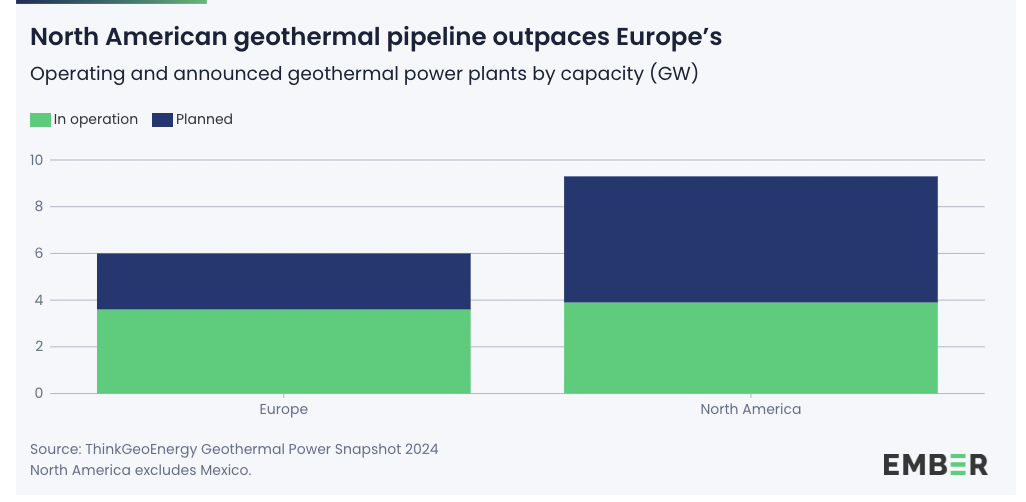

Despite this progress, Europe is at risk of losing ground. Lengthy permitting processes, inconsistent national support and the absence of a coordinated EU strategy and accompanying policies have slowed commercial deployment. In contrast, projects in the United States and Canada are now scaling up many of the methods first tested in Europe, supported by targeted policy incentives and private investment. Delayed deployment also risks shifting learning effects, supply-chain development and cost reductions to other regions, increasing future costs for European projects even where resources are available. Without a stronger focus on market-scale financing, Europe may miss the economic and industrial benefits of technologies it helped pioneer.

Geothermal power plants could play a crucial role in meeting the fast-growing electricity demand of data centres, whose global consumption could more than double by the early 2030s. As data-centre capacity expands, geothermal offers a stable, always-available source of electricity that can be developed alongside these sites. Its continuous output helps balance the wider power system and reliably serves data centres energy-intensive operations over the long term.

Recent research by Project InnerSpace shows that if current clustering trends continue, geothermal could economically meet up to 64 percent of new data centre demand in the US by the early 2030s and even more when developments are located near optimal resources.

At the same time, AI is reshaping geothermal development. By analysing seismic and geological data, it helps identify promising sites, streamline drilling and improve performance – creating a feedback loop in which each technology accelerates the other.

Major technology companies are no longer experimenting with geothermal – they are deploying it. Announced in 2021 and now fully operational, Google’s partnership with Fevro marked the world’s first enhanced geothermal project built for a data centre. Others are following suit, with Meta signing a 150-megawatt deal with Sage Geosystems in the United States. In Europe, no similar cooperations were announced.

In the United States, geothermal power is now firmly within the clean-energy toolkit. Federal legislation such as the Inflation Reduction Act has expanded investment and production tax credits to include geothermal electricity, establishing clearer economic signals for developers. Meanwhile, geothermal enjoys bipartisan backing because it leverages drilling and subsurface expertise tied to familiar industries and offers around-the-clock output.

In Europe, several Member States, including Austria, Croatia, France, Hungary, Ireland, and Poland, have developed national geothermal road maps aimed at supporting subsurface investment, demonstration wells and domestic supply chains, in some cases backed by dedicated financing and targets.

Only more recently has momentum begun to build at the EU level. In 2024, both the EU Council and the Parliament voiced their support for accelerating geothermal and proposed a European Geothermal Alliance, to be set up by the Commission. As geothermal strongly aligns with the EU’s priorities on competitiveness, energy security and industrial decarbonisation, the forthcoming European Geothermal Action Plan is a much-needed and timely development.

However, translating strategic recognition into deployment will depend on how geothermal is integrated across broader EU policy instruments. As preparations for the next Multiannual Financial Framework advance, and initiatives such as the Industrial Decarbonisation Accelerator Act aim to strengthen permitting and demand signals for clean solutions, geothermal’s high upfront risk, long asset lifetimes and system value as a source of firm capacity make coordinated EU action particularly important. In practice, the effectiveness of European geothermal framework will hinge on progress in three areas at EU level:

Download the report here.

Hot stuff: geothermal energy in Europe [PDF]

Techno-economic geothermal capacity potentials for power in the EU are aggregated from data presented in the paper “Global geothermal electricity potentials: A technical, economic, and thermal renewability assessment” by Franzmann et al., whose cost curves are limited to the “Gringarten approach” for reservoir modelling (please refer to the original publication for further details).

Raw geothermal energy surface densities in Europe are computed starting from Global Volumetric Potential (GVP) data from the Geomap tool by Project Innerspace, in particular from the modules with 150 °C cutoff temperature (minimum for power applications) and depths of 2000 m, 5000 m and 7000 m.

GVP data points, reported on a geographical grid with 0.17×0.17 degrees latitude-longitude resolution, are then averaged over the surface of each analysed country to obtain national energy values, expressed in PJ/km2.

The conversion to useful electrical energy is then performed by multiplying each country’s total by exergy efficiency (~30%, based on a 150 °C temperature for hot rock and on a 25 °C temperature for ambient) and utilization (~20%, based on conservative ranges out of the GEOPHIRES v2.0 simulation tool) factors. Capacity equivalents are calculated assuming an 80% load factor and a 25-years lifetime for a modern geothermal power plant. Results from the steps in this paragraph were used to validate the methodology through benchmarking with aggregated values from “The Future of Geothermal Energy” report by IEA.

The extraction of the original GVP data by Project Innerspace was performed in November 2025. Features and availability of modules within the Geomap tool might have changed since then.

Estimates for electricity generation in the EU are based on an 80% load factor, consistent with the rest of the methodology and representative of modern geothermal power plants. While cumulative generation and capacity estimates for 2025 only would yield a load factor of around 65%, future technological (improvements in plant operations) and market (increases in electrification and grid availability) conditions can justify assumptions for utilization of geothermal power capacity at or above this level.

Throughout the report, “Europe” refers to the European Union plus Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Türkiye, United Kingdom and Western Balkan countries, reflecting the geographical scope of geological resource assessments and existing geothermal deployment. Where analysis refers specifically to the European Union, this is stated explicitly.

The authors would like to thank several Ember colleagues for their valuable contributions and comments, including Elisabeth Cremona, Pawel Czyzak, Reynaldo Dizon, Burcu Unal Kurban, Eli Terry, and others.

We would also like to extend our gratitude to our partners Clean Air Task Force and European Geothermal Energy Council for providing external review as well as valuable data and insights.