Over the past decade or so, the Connecticut Green Bank, the first green bank in the United States, has taken on an unusual role — that of a “public developer” of solar projects for schools, cities, and low-income housing across the state.

“There are all sorts of public institutions that take in public money and give a loan, a grant, and that’s all they do,” said Jason Kowalski, executive director of the Public Renewables Project. “This is completely different in what it can achieve.”

The Connecticut Green Bank’s Solar Marketplace Assistance Program Plus (Solar MAP+) actively engages in originating, developing, and even owning projects, he said. To date, the program has deployed $145 million in capital on nearly 54 megawatts’ worth of solar projects that are expected to help save a collective $57 million in energy costs, according to bank data shared with Canary Media.

Though the approach is unusual for a public entity, it needn’t be, Kowalski said. In fact, it is a model that cash-strapped state governments should consider closely as federal clean-energy tax credits disappear and energy costs rise. That’s particularly true for the 16 states, plus the District of Columbia, that have created a government-backed or nonprofit green bank since Connecticut first launched its version in 2011.

The bank’s program targets sectors that private lenders and solar developers might shy away from because of perceived credit risks or low returns on investment, Kowalski explained. It taps into low-cost financing available to state entities and builds portfolios of projects to achieve economies of scale.

Then the revenues generated from those projects are “recycled”: used to expand the pool of capital from which it can make loans for other projects that help achieve Connecticut’s clean energy and environmental justice goals.

While some private-sector solar industry players may see the Solar MAP+ approach as infringing on their turf, state-backed agencies “see it as expanding the role of the private-sector installation business,” Kowalski said.

That’s certainly the case for the school solar projects that Solar MAP+ has built, said Tish Tablan, senior program director at Generation180, a clean energy advocacy group.

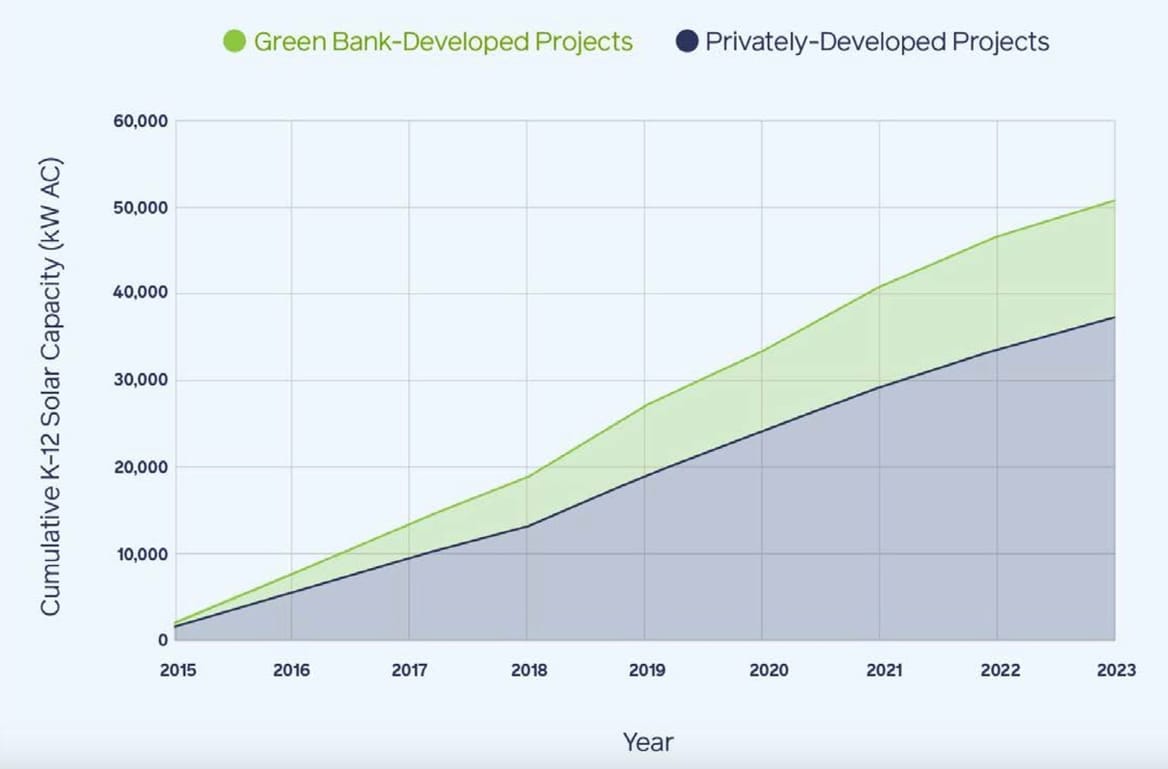

A September report by Tablan’s and Kowalski’s groups and the Climate Reality Project found that Connecticut — the third-smallest state by land mass and 29th in population — ranks fifth in the country for total solar capacity installed on K–12 schools and second (behind Hawaii) in the percentage of K–12 schools with solar.

The Connecticut Green Bank developed 27% of school solar installations in the state from 2015 to 2023, according to the report. Those installations are projected to save schools tens of millions of dollars in energy costs, and more than half are in low-income and disadvantaged communities.

The same model can help schools and public buildings do more than solar, Tablan added. “We can look at electrification, we can look at heat pumps, we can look at solar-plus-storage, we can look at microgrids.”

This kind of financial support is increasingly important as the Trump administration cancels federal funding for clean energy projects more broadly, and in disadvantaged communities in particular, Tablan and Kowalski said. That includes the administration’s move to claw back $20 billion in federal “green bank” funds meant to promote precisely this kind of public-sector finance, which is now being challenged in court.

Solar MAP+ evolved largely as a response to gaps in the state’s broader solar market, said Mackey Dykes, the Connecticut Green Bank’s executive vice president of financing programs.

The same 2011 law that launched the bank also created state solar incentives meant to boost development across multiple sectors of the economy, Dykes said. “But there were some areas where we didn’t see a lot of activity. We sat down and started to figure out why that was.”

The first targets were state agencies that were lagging in solar development, despite their access to relatively low-cost capital, he said. This indicated that incentives alone weren’t the solution. It turned out that those agencies “needed help with documentation structures, with procurement, with project labor agreements,” he said. “We put that together, and projects started happening.”

“Then we realized we built this Swiss Army knife of tools that we could bring to bear in other sectors where there were gaps in solar deployment,” Dykes said. The Connecticut Green Bank also started looking at municipalities that were lagging in using solar incentives, particularly smaller towns, he said. At around the same time, he noted, “we realized the solar incentive program in the state was undersubscribed for school projects,” and they set out to fix that.

Bundling multiple school projects can help lower costs. Dykes cited the example of a 67-kilowatt system at an intermediate school in Portland, Connecticut. “You’d have trouble attracting attention for a project that small,” he said. “When you combine it with dozens of projects, and have developers competing with a pool of projects, the projects become more feasible,” with the Connecticut Green Bank serving as a clearinghouse for hiring installers and securing financing at a larger scale.

Tablan highlighted the similarities with Generation180’s work with schools. “If you ask any public-sector entity, they’re going to say budget and cost are the first concerns,” she said. Most of the country’s school solar projects have been developed via third-party ownership models, and “Connecticut Green Bank has taken that approach” as well, she said.

The wraparound services that Solar MAP+ offers bring more than money to the equation, said Advait Arun, senior associate for capital markets at the Center for Public Enterprise. The nonprofit think tank uses the term “public development” to characterize the way public entities can expand beyond financing to include “all of the steps in a project development pipeline,” including ownership, operations, and maintenance.

That’s not a normal role for green banks, Arun said. As of the end of 2023, green banks and partners had driven a cumulative $25.4 billion in public and private investments, according to the Coalition for Green Capital, a group that includes green banks and environmental advocacy organizations. Most of that funding has focused on de-risking harder-to-finance sectors, such as energy efficiency and rooftop solar installations in low-income neighborhoods, without taking the plunge into the full range of project development activities that Solar MAP+ is involved in.

But even under this model, there are gaps that private sector financiers don’t want to fill. That’s where public-sector ownership can help, as the data on school solar’s growth in Connecticut indicates, Arun noted.

“We’re not used to this kind of thing in this country,” he said. But “without the Connecticut Green Bank de-risking schools for this kind of solar investment, the market would have remained smaller than it could be.”

That direct involvement has helped smaller school districts build more ambitious project pipelines over time, said Emily Basham, director of financing programs for Solar MAP+.

In Manchester, Connecticut, once the private developers caught wind of state involvement, city leaders “were somewhat bombarded with proposals,” Basham said. “They wanted to do their first projects with us, to cut their teeth on it.”

The more than $100,000 in projected annual energy savings from the solar systems at seven municipal buildings, including six schools, helped the city gain confidence in moving forward with a subsequent project that has converted one of its elementary schools into the state’s first net-zero school by adding advanced insulation systems and on-site geothermal energy, she said.

The Connecticut Green Bank’s dive into parts of the project development process has drawn fire from solar industry groups in the state.

In 2024, solar developers pushed lawmakers to restrict the bank from developing projects at schools and municipal sites, citing concerns around a lack of competitive bidding. That effort was defeated after representatives of state and local government as well as labor and clean-energy advocates at the Connecticut Roundtable on Climate and Jobs weighed in to support the bank.

Some of those supporters came from Branford, Connecticut, which contracted with the Connecticut Green Bank to build solar arrays on two elementary schools.

“We’re a municipality with limited staff and dedicated volunteers, but you can’t ask volunteers to procure and oversee a project of that size,” said Jamie Cosgrove, who recently ended a 12-year stint as Branford’s first selectman — the equivalent of the town’s mayor — to join the Connecticut Green Bank’s board of directors. “We use them as a trusted source, and we feel comfortable engaging with them to move forward on a number of these projects.”

The two elementary schools’ solar installations are expected to save about $248,000 over the next 20 years, Cosgrove noted — not a huge payback for a private-sector developer. “Maybe these projects aren’t significantly cash-flow positive. But there are other priorities we have as a municipality. We’re looking to advance our clean energy goals.”

Branford has also done plenty of work with the private sector, including a 4.3-megawatt solar array on a former gravel yard and solar projects at the town’s high school and fire station, said Jim Finch, Branford’s finance director. “It’s not an either-or thing,” he said.

“I don’t think it’s unreasonable for a state entity that’s identified reducing carbon emissions as a public purpose to do this kind of work,” Finch added. “We have organizations to deal with clean air, financing sewer projects, et cetera — we can have public purpose entities do that.”

State development finance agencies — government entities in all 50 states that support economic development through a variety of financing structures — could also take on this kind of public developer model, he said.

New York could be a first target, said Kowalski of the Public Renewables Project. The New York Power Authority, the public agency that owns and develops transmission and generation in the state, has been tasked with building gigawatts of large-scale renewables. Backers of more muscular government intervention to rejuvenate the state’s faltering progress on clean energy are calling for the NYPA to follow Connecticut’s lead in building solar on school rooftops.

Finding ways to push more finance into solar projects has become a more pressing matter, Kowalski said, both to offset the loss of solar tax credits from the megalaw passed by Republicans in Congress this summer and to combat fast-rising electricity costs across the country.

“Our whole report is an answer to how to respond to the tax credits getting rolled back. If there’s a shortfall, we think we have an answer,” Kowalski said. “Public developer models can be part of an affordability agenda on climate.”