A debate playing out in Wisconsin underscores just how challenging it is for U.S. states to set policies governing data centers, even as tech giants speed ahead with plans to build the energy-gobbling computing facilities.

Wisconsin’s state legislators are eager to pass a law that prevents the data center boom from spiking households’ energy bills. The problem is, Democrats and Republicans have starkly different visions for what that measure should look like — especially when it comes to rules around hyperscalers’ renewable energy use.

Republican state legislators introduced a bill last week that orders utility regulators to ensure that regular customers do not pay any costs of constructing the electric infrastructure needed to serve data centers. It also requires data centers to recycle the water used to cool servers and to restore the site if construction isn’t completed.

Those are key protections sought by decision-makers across the political spectrum, as opposition to data centers in Wisconsin and beyond reaches a fever pitch.

But the bill will likely be doomed by a “poison pill,” as consumer advocates and manufacturing-industry sources describe it, that says all renewable energy used to power data centers must be built on-site.

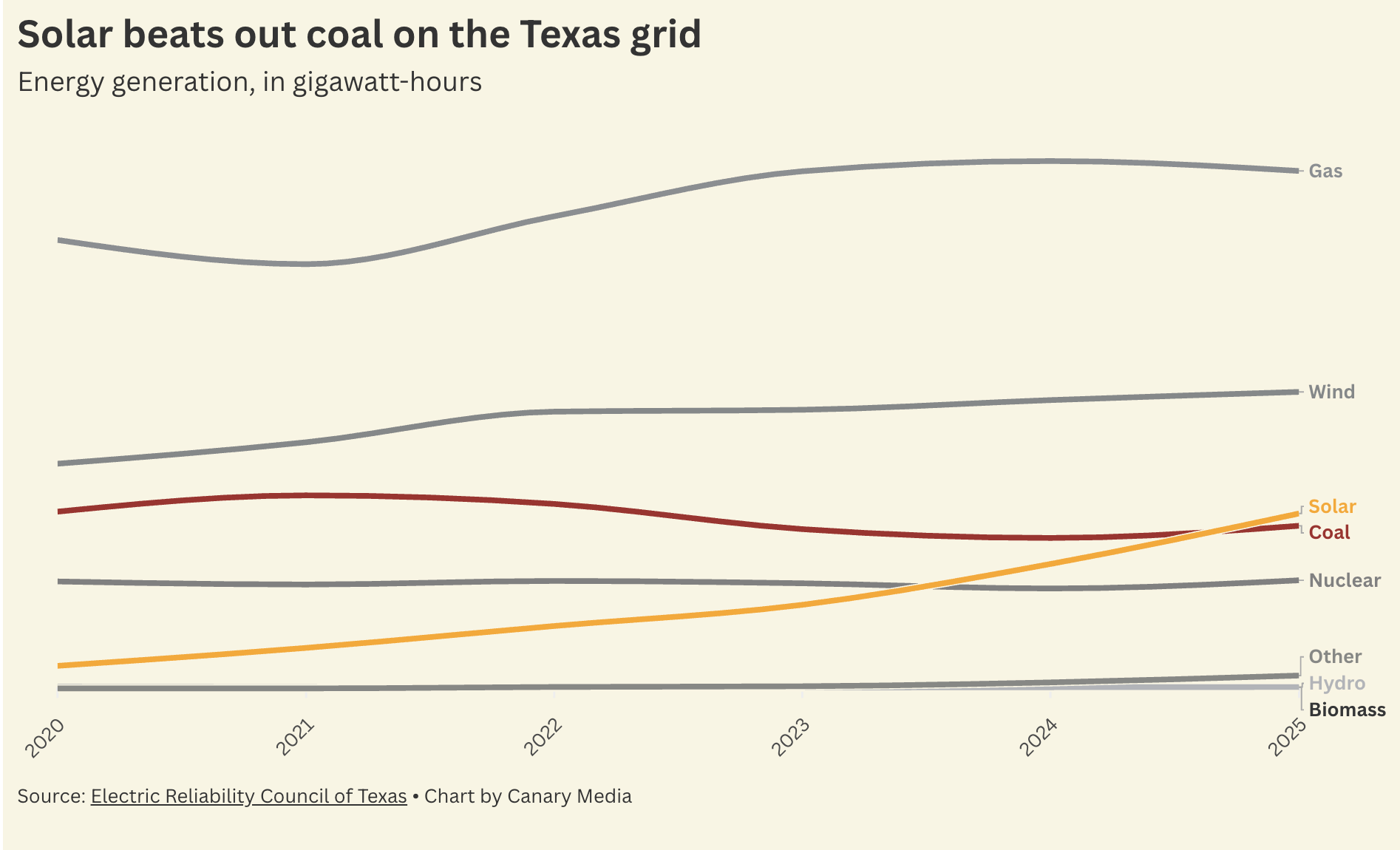

Republican lawmakers argue this provision is necessary to prevent new solar farms and transmission lines from sprawling across the state.

“Sometimes these data centers attempt to say that they are environmentally friendly by saying we’re going to have all renewable electricity, but that requires lots of transmission from other places, either around the state or around the region,” said State Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, a Republican, at a press conference this week. “So this bill actually says that if you are going to do renewable energy, and we would encourage them to do that, it has to be done on-site.”

This effectively means that data centers would have to rely largely on fossil fuels, given the limited size of their sites and the relative paucity of renewable energy in the state thus far.

Gov. Tony Evers and his fellow Democrats in the state legislature are unlikely to agree to this scenario, Wisconsin consumer and clean-energy advocates say.

Democrats introduced their own data center bill late last year, some of which aligns closely with the Republican measure: The Democratic bill would similarly block utilities from shifting data center costs onto residents, by creating a separate billing class for very large energy customers. It would require that data centers pay an annual fee to fund public benefits such as energy upgrades for low-income households and to support the state’s green bank.

But that proposal may also prove impossible to pass, advocates say, because of its mandate that data centers get 70% of their energy from renewables in order to qualify for state tax breaks, and a requirement that workers constructing and overhauling data centers be paid a prevailing wage for the area. This labor provision is deeply polarizing in Wisconsin. Former Republican Gov. Scott Walker and lawmakers in his party famously repealed the state’s prevailing-wage law for public construction projects in 2017, and multiple Democratic efforts to reinstate it have failed.

The result of the political division around renewables and other issues is that Wisconsin may accomplish little around data center regulation in the near term.

“If we could combine the two and make it a better bill, that would be ideal,” said Beata Wierzba, government affairs director for the nonprofit clean-energy advocacy group Renew Wisconsin. “It’s hard to see where this will go ultimately. I don’t foresee the Democratic bill passing, and I also don’t know how the governor can sign the Republican bill.”

Urgent need

Wisconsin’s consumer and clean energy advocates are frustrated about the absence of promising legislation at a time when they say regulation of data centers is badly needed. The environmental advocacy group Clean Wisconsin has received thousands of signatures on a petition calling for a moratorium on data center approvals until a comprehensive state plan is in place.

At least five new major data centers are planned in the state, which is considered attractive for the industry because of its ample fresh water and open land, skilled workers, robust electric grid, and generous tax breaks. The Wisconsin Policy Forum estimated that data centers will drive the state’s peak electricity demand to 17.1 gigawatts by 2030, up from 14.6 gigawatts in 2024.

Absent special treatment for data centers, utilities will pass the costs on to customers for the new power needed to meet the rising demand.

Two Wisconsin utilities — We Energies and Alliant Energy — are proposing special tariffs that would determine the rates they charge data centers. Allowing utilities in the same state to have different policies for serving data centers could lead to these projects being located wherever utilities offer them the cheapest rates, and result in a patchwork of regulations and protections, consumer advocates argue. They say legislation should be passed soon, to standardize the process and enshrine protections statewide before utilities move forward on their own.

Some of Wisconsin’s neighbors have already taken that step, said Tom Content, executive director of Wisconsin’s Citizens Utility Board, a consumer advocacy group.

He pointed to Minnesota, where a law passed in June mandates that data centers and other customers be placed in separate categories for utility billing, eliminating the risk of data center costs being passed on to residents. The Minnesota law also protects customers from paying for “stranded costs” if a data center doesn’t end up needing the infrastructure that was built to serve it.

Ohio, by contrast, provides a cautionary tale, Content said. After state regulators enshrined provisions that protected customers of the utility AEP Ohio from data center costs, developers simply looked elsewhere in the state.

“Much of the data center demand in Ohio shifted to a different utility where no such protections were in place,” Content said. “We’re in a race to the bottom. Wisconsin needs a statewide framework to help guide data center development and ensure customers who aren’t tech companies don’t pick up the tab for these massive projects.”

Clean energy quandary

Limiting clean energy construction to data center sites could be especially problematic, as data center developers often demand renewable energy to meet their own sustainability goals.

For example, the Lighthouse data center — being developed by OpenAI, Oracle, and Vantage near Milwaukee — will subsidize 179 megawatts of new wind generation, 1,266 megawatts of new solar generation, and 505 megawatts of new battery storage capacity, according to testimony from one of the developers in the We Energies tariff proceeding.

But Lighthouse covers 672 acres. It takes about 5 to 7 acres of land to generate 1 megawatt of solar energy, meaning the whole campus would have room for only about a tenth of the solar the developers promise.

We Energies is already developing the renewable generation intended to serve that data center, a utility spokesperson said, but the numbers show how future clean energy could be stymied by the on-site requirement.

“It’s unclear why lawmakers would want to discriminate against the two cheapest ways to produce energy in our state at a time when energy bills are already on the rise,” said Chelsea Chandler, the climate, energy, and air program director at Clean Wisconsin.

Renew Wisconsin’s Wierzba said the Democrats’ 70% renewable energy mandate for receiving tax breaks could likewise be problematic for tech firms.

“We want data centers to use renewable energy, and companies I’m aware of prefer that,” she said. “The way the Republican bill addresses that is negative and would deter that possibility. But the Democratic bill almost goes too far — 70%. That’s a prescribed amount, too much of a hook and not enough carrot.”

Alex Beld, Renew Wisconsin’s communications director, said the Republican bill might have a hope of passing if the poison pill about on-site renewable energy were removed.

“I don’t know if there’s a will on the Republican side to remove that piece,” he said. “One thing is obvious: No matter what side of the political aisle you’re on, there are concerns about the rapid development of these data centers. Some kind of legislation should be put forward that will pass.”

Bryan Rogers, environmental director of the Milwaukee community organization Walnut Way Conservation Corp, said elected officials shouldn’t be afraid to demand more of data centers, including more public benefit payments.

“We know what the data centers want and how fast they want it,” he said. “We can extract more concessions from data centers. They should be paying not just their full way — bringing their own energy, covering transmission, generation. We also know there are going to be social impacts, public health, environmental impacts. Someone has to be responsible for that.”

Utility representatives expressed less urgency around legislation.

William Skewes, executive director of the Wisconsin Utilities Association, said the trade group “appreciates and agrees with the desire by policymakers and customers to make sure they’re not paying for costs that they did not cause.”

But, he said, the state’s utility regulators already do “a very thorough job reviewing cases and making sure that doesn’t happen. Wisconsin utilities are aligned in the view that data centers must pay their full share of costs.”

If Wisconsin legislators do manage to pass data center legislation this session, it will head to the desk of Evers. The governor is a longtime advocate for renewables, creating the state’s first clean energy plan in 2022, and he has expressed support for attracting more data centers to Wisconsin.

“I personally believe that we need to make sure that we’re creating jobs for the future in the state of Wisconsin,” Evers said at a Monday press conference, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “But we have to balance that with my belief that we have to keep climate change in check. I think that can happen.”

.svg)