U.S. utilities are spending more than ever on their transmission grids. So why has the construction of new long-range, high-voltage power lines — the kind that experts say the country desperately needs — slowed over the past decade?

Claire Wayner, a senior associate at think tank RMI, says one big reason is that utilities are opting to build smaller-scale transmission projects that earn them guaranteed profits instead of large ones that are more difficult to plan but deliver greater benefits for ratepayers.

In a November report, Wayner and her co-authors examine the blind spot in utility regulation that they say is at the root of the problem — a “regulatory gap” that prevents both federal and state regulators from exercising meaningful oversight of the smaller transmission projects utilities build within their own territories.

Many of these projects are clearly needed to bolster parts of the grid that were built more than half a century ago. But with less oversight, they tend to cost utility customers more than bigger, regionally planned grid projects, which require utilities, state regulators, and regional grid operators to assess costs and benefits and agree on how to share construction expenses.

That’s a complex and time-consuming process. But the longer-range, higher-voltage power lines that typically result can deliver far greater benefits per dollar of investment than piecemeal, utility-by-utility buildouts, according to analysis of previous regional expansions by the grid operators responsible for managing them.

Wayner thinks reforms are needed to push utilities and grid operators to take what RMI’s report calls a “regional-first” approach. “You could be addressing local and regional needs simultaneously and meeting both needs in a more efficient manner,” she said.

Today, however, transmission planning is like “two different cars being driven on two different roads in parallel. The regional road is like a toll road with all these checkpoints: identify regional needs, open competitive bidding windows, identify the costs and benefits,” she said. “The local road has no speed limits. [Utilities] can build as much as they want.”

The U.S. needs more regional transmission than ever to allow clean energy to replace retiring fossil-fuel power plants, to transmit energy further and clear grid congestion spots, and to make the grid more resilient against extreme weather. But the more local projects eat up money, the less there is for projects that could deliver bigger benefits.

The result, Wayner said, has been “rapidly increasing transmission rates, while the buildout of mileage of high-voltage transmission lines is at an all-time low.”

The regulatory gap identified in the RMI report stems from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s Order 1000, which, somewhat ironically, intended to push utilities, state regulators, and regional grid operators to do more cost-effective regional grid planning.

The order, passed in 2011 and put into effect in 2014 after overcoming court challenges, created regional grid planning entities across almost all of the country. States and utilities within them must undertake coordinated planning of grid projects and agree on methods to share the costs of building them.

But Order 1000 also included exemptions. “Local” projects under certain voltage thresholds within individual utilities’ service territories don’t have to be part of regional planning. Neither do “asset management” projects that rebuild or refurbish existing transmission lines. Perhaps not coincidentally, since the order went into effect, these exempted projects have grown to make up most transmission investment.

FERC Order 1000 also requires that regional transmission projects be opened to competition from independent transmission developers, with the goal of driving down costs. But grid experts, including former FERC commissioners involved in crafting the rule, have conceded that this provision has driven utilities to seek out local and asset-management projects that evade competitive bidding.

These various policies and exemptions — and their implications for federal, regional, and state authorities — are at the heart of the regulatory gap, Wayner explained in a December webinar discussing RMI’s report.

At the federal level, FERC allows utilities to earn guaranteed profits on exempted projects under a so-called “formula rate” structure, which “does not require project-level scrutiny,” Wayner said. Thus, “most local projects receive virtually automatic rate approval.”

At the state level, utility regulators can require local projects to secure state permits. But many exempted projects are bundled into infrastructure spending requests within sprawling and complex utility rate cases, which makes it much harder for regulators to demand more information about them.

What’s more, FERC sets the rates of return that utilities can earn from these small-scale transmission investments, so states have few openings to demand that utilities prove they’re the most cost-effective option, Wayner said.

As for the planning entities and grid operators that manage regional planning, they’re not actually regulators, said Ari Peskoe, director of the Electricity Law Initiative at Harvard University. Instead, they’re organizations made up of the same utilities that are incentivized to push projects that maximize profits.

“There are lots of reasons why these projects are more attractive financially for the utilities than more ambitious regional projects that we might need for clean energy and reliability,” said Peskoe, who is a longtime critic of monopoly-utility transmission policies. “They’re easier to execute. You don’t have to publicly disclose details that could bring more scrutiny. You may need no state or local permits, particularly if you’re rebuilding existing infrastructure.”

These are all well-known problems, and FERC held a technical conference in 2022 that allowed critics to lay out proposals for fixing them, he said. But it’s not clear if or how FERC might initiate a proceeding to take further steps to reform the status quo.

“The real problem with this local spending is that we have no idea what value the public might be getting,” Peskoe said. “It’s hard to even tally up the bills.”

There’s no doubt that costs are growing. Consultancy The Brattle Group has tracked data from FERC and utility trade group Edison Electric Institute showing a steady rise in U.S. transmission spending over the past two decades. Since FERC Order 1000 went into effect, more than 90% of transmission spending has gone to projects that don’t undergo cost-benefit analysis, and about half of those investments are in local and asset-management projects that fall into the regulatory gap.

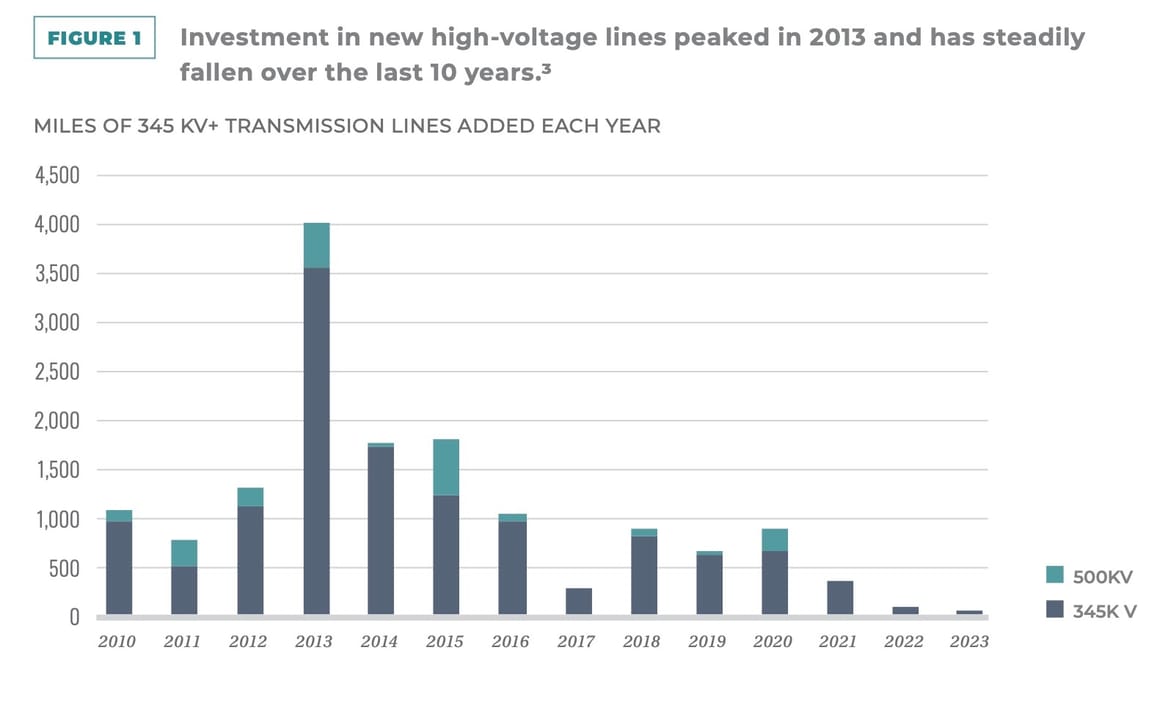

There’s also been a steady decline in new high-voltage transmission projects over the past decade. According to RMI’s November report, spending on projects of 230 kilovolts and above — the kind typically built in regional grid projects — has fallen from 72% of total transmission spending in 2014 to 34% of spending in 2021.

And a July report from consultancy Grid Strategies found projects of 345 kilovolts and above have fallen from an average of 1,700 miles per year from 2010 to 2014 to 350 miles per year from 2020 to 2023, including an all-time low of 55 new miles in 2023.

That’s not to say that regional grid expansions aren’t happening. In some parts of the country, including much of the Midwest, utilities and state regulators have agreed to tens of billions of dollars of grid projects expected to yield cost, climate, and reliability improvements. FERC Order 1920, passed last year, orders grid operators and utilities across the country to undertake similarly ambitious efforts.

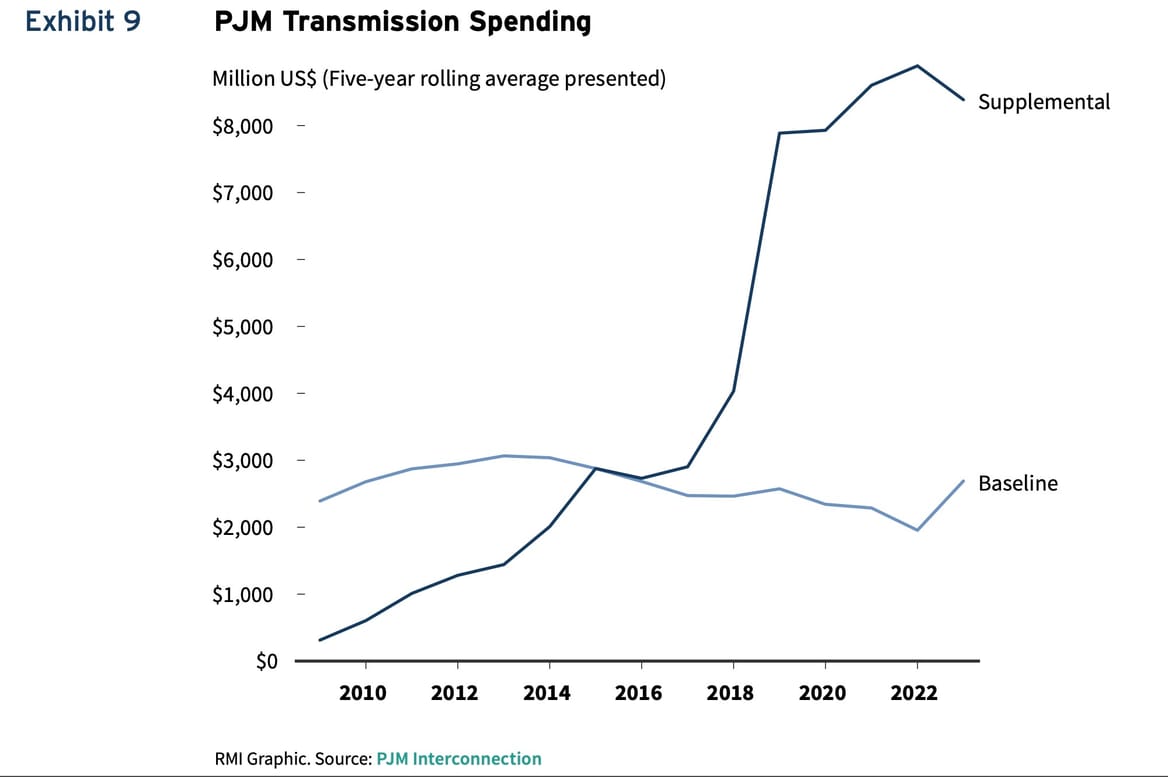

But elsewhere, the chasm between regional and local projects has become extreme. In the territory of PJM, the grid operator that serves Washington, D.C., and 13 states from Illinois to Virginia, RMI calculated that the five-year averages for spending on “supplemental” projects — PJM’s term for local projects — ballooned from less than $1 billion per year in 2010 to more than $8 billion per year since 2020. Meanwhile, the same averages for spending on “baseline” projects not subject to Order 1000’s exemptions declined.

Just because a transmission project falls into the regulatory gap doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be built, said Rob Gramlich, president of Grid Strategies. For one thing, much of the money spent on local projects over the past decade has gone to “replacing assets that are 50 or 60 or more years old,” he said.

But Tyson Slocum, director of the energy program at nonprofit watchdog group Public Citizen, said the inability to review or challenge these projects is a problem.

“Transmission owners, and [regional transmission organizations] to a certain extent, have lots of incentives to prioritize the projects that maximize returns for them but not necessarily for the consumers,” he said. It’s particularly troubling when utilities may be using that lack of transparency to squeeze their customers for more money than they really need.

Slocum suspects that’s what happened with a transmission project at the heart of a December settlement agreement between FERC and New Jersey utility Public Service Electric and Gas Co. (PSE&G). The utility agreed to pay a $6.6 million fine to settle allegations that it failed to provide “accurate and factual information” regarding a $546 million project to rebuild a transmission line with towers built nearly a century ago.

Among the disclosure failures cited in FERC’s enforcement action was PSE&G’s presentation to PJM stating that a consultant had found that 67 of those towers needed extensive foundation retrofits. In fact, the consultant had found only eight towers needed such work — presumably a much less costly scope of work than what PSE&G ended up doing.

PSE&G neither admitted nor denied the allegations, and the settlement with FERC does not require it to forgo revenues it will receive for the project under FERC’s formula rates. Public Citizen filed a protest with FERC this month challenging PJM’s plan to assign those costs to ratepayers, citing PSE&G’s December settlement agreement as evidence of “harrowing fraud” from the utility and a failure by PJM to “perform a modicum of independent oversight.” PSE&G told Utility Dive that it will “vigorously defend” against Public Citizen’s allegations of imprudence.

Slocum called the PSE&G case “an easy-to-understand example of how bad things can get when you don’t have independence in assessing these transmission projects, when you don’t have someone in the room asking hard questions.”

PJM spokesperson Jeff Shields told Canary Media that PJM has “enhanced the transparency of its supplemental projects processes” in recent years. But he added that “authority and expertise for certain asset management decisions remain with transmission owners under settled FERC precedent.”

Nor can New Jersey utility regulators challenge the utility’s rate recovery on their own. Harvard’s Peskoe highlighted this as a problem that FERC will need to step in to solve since the agency regulates these rates. “If you find that utilities went way over budget on a project, there’s nothing the state can do but go to FERC and complain about it,” he said

State regulators sometimes take actions that undermine what little oversight they do have over utility investments. Utility Florida Power & Light has faced criticism over a 176-mile transmission line that it designed at an unusually low voltage, allowing the endeavor to skirt the rigorous review required for higher-voltage regional projects. Critics say that earlier decisions by the Florida Public Service Commission paved the way for that project to escape more scrutiny.

Other states have taken more aggressive steps to demand better transparency. RMI’s report highlights Kansas, which passed a law in 2023 giving regulators authority to demand that utilities provide detailed information, hold public workshops, and accept a state-set rate of return if they want to pursue a streamlined process to earn revenues on money spent on local transmission projects.

But watchdogging individual local transmission projects doesn’t fix the underlying problem described in RMI’s report: Regional planning has been relegated to second-run status behind local projects.

Instead of executing local projects on a separate track from regional projects, utilities and regional planning organizations should be required to “first look at how regional projects could holistically meet local and regional needs, and then build any local projects necessary to meet remaining local needs,” Wayner said during the December webinar.

FERC Order 1920 does require utilities, planning entities, and grid operators to undertake some major long-term grid planning reforms. But Wayner and Peskoe agreed that its adjustments don’t close the local-project regulatory gap.

Most notably, when grid operators hold meetings to share local transmission project data with state regulators and other stakeholders, utilities and the grid operator don’t have to respond to any questions or data requests from stakeholders.

FERC’s order modeled this approach on PJM’s method for managing those meetings, which have been a longtime frustration for Greg Poulos, the executive director of the nonprofit Consumer Advocates of the PJM States. “We are given a sticker price of projects,” he said during the December webinar. “We can’t get any other information. We can ask questions. They do not have to be answered.”

That lack of transparency is a big problem, said Kent Chandler, a former chairman for the Kentucky Public Service Commission and resident senior fellow at free market-oriented think tank R Street Institute. Utilities are monopolies that get to charge captive customers for reliable and affordable power, he said during the December webinar. “It shouldn’t be on us to have to prove the negative on why we’re not getting the best value for our money.”

These concerns have spurred a new effort to get FERC to intervene. In December, R Street Institute, consumer advocates including Public Citizen, and groups representing industrial energy consumers filed a complaint asking FERC to require that lower-voltage lines typically built under the “local” designation be brought into the same regional planning structures that govern higher-voltage lines.

It also calls for “independent transmission system planners,” a new kind of regional planner watchdog that would counterbalance “the self-interest and undue influence of existing transmission providers.”

Maryland’s Office of People’s Counsel, which advocates for residential utility consumers in the state, joined that complaint. David Lapp, who leads the office, said the goal is to “stop being nickel and dimed in massive amounts” for local transmission projects.

Under today’s regulatory gap, “we have situations where two adjacent utilities might be spending hundreds of millions each,” he said. “You might be able to have a project that cuts those costs in half if they were part of a regional plan.”

Lapp noted that in PJM’s territory, “investments made at a higher cost are lost opportunities for better spending on what’s really going to help customers going forward as well as advance climate policy.”

PJM is facing a massive backlog in processing hundreds of gigawatts of clean energy projects seeking to interconnect to its grid, a lag that some analysts say has been exacerbated by its refusal to engage in large-scale regional grid planning and expansions. “We may be looking at that lost-opportunity cost with the stalled interconnection queue and the inability to get more clean energy on the grid,” Lapp said.