This is the second article in our series “Boon or bane: What will data centers do to the grid?”

There’s no question that data centers are about to cause U.S. electricity demand to spike. What remains unclear is by how much.

Right now, there are few credible answers. Just a lot of uncertainty — and “a lot of hype,” according to Jonathan Koomey, an expert on the relationship between computing and energy use. (Koomey has even had a general rule about the subject named after him.) This lack of clarity around data center power requires that utilities, regulators, and policymakers take care when making choices.

Utilities in major data center markets are under pressure to spend billions of dollars on infrastructure to serve surging electricity demand. The problem, Koomey said, is that many of these utilities don’t really know which data centers will actually get built and where — or how much electricity they’ll end up needing. Rushing into these decisions without this information could be a recipe for disaster, both for utility customers and the climate.

Those worries are outlined in a recent report co-authored by Koomey along with Tanya Das, director of AI and energy technology policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, and Zachary Schmidt, a senior researcher at Koomey Analytics. The goal, they write, “is not to dismiss concerns” about rising electricity demand. Rather, they urge utilities, regulators, policymakers, and investors to “investigate claims of rapid new electricity demand growth” using “the latest and most accurate data and models.”

Several uncertainties make it hard for utilities to plan new power plants or grid infrastructure to serve these data centers, most of which are meant to power the AI ambitions of major tech firms.

AI could, for example, become vastly more energy-efficient in the coming years. As evidence, the report points to the announcement from Chinese firm DeepSeek that it replicated the performance of leading U.S.-based AI systems at a fraction of the cost and energy consumption. The news sparked a steep sell-off in tech and energy stocks that had been buoyed throughout 2024 on expectations of AI growth.

It’s also hard to figure out whose data is trustworthy.

Companies like Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, OpenAI, Oracle, and xAI each have estimates of how much their demand will balloon as they vie for AI leadership. Analysts also have forecasts, but those vary widely based on their assumptions about factors ranging from future computing efficiency to manufacturing capacity for AI chips and servers. Meanwhile, utility data is muddled by the fact that data center developers often surreptitiously apply for interconnection in several areas at once to find the best deal.

These uncertainties make it nearly impossible for utilities to gauge the reality of the situation, and yet many are rushing to expand their fleets of fossil-fuel power plants anyway. Nationwide, utilities are planning to build or extend the life of nearly 20 gigawatts’ worth of gas plants as well as delaying retirements of aging coal plants.

If utilities build new power plants to serve proposed data centers that never materialize, other utility customers, from small businesses to households, will be left paying for that infrastructure. And utilities will have spent billions in ratepayer funds to construct those unnecessary power plants, which will emit planet-warming greenhouse gases for years to come, undermining climate goals.

“People make consequential mistakes when they don’t understand what’s going on,” Koomey said.

Some utilities and states are moving to improve the predictability of data center demand where they can. The more reliable the demand data, the more likely that utilities will build only the infrastructure that’s needed.

In recent years, the country’s data center hot spots have become a “wild west,” said Allison Clements, who served on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission from 2020 to 2024. “There’s no kind of source of truth in any one of these clusters on how much power is ultimately going to be needed,” she said during a November webinar on U.S. transmission grid challenges, hosted by trade group Americans for a Clean Energy Grid. “The utilities are kind of blown away by the numbers.”

A December report from consultancy Grid Strategies tracked enormous load-forecast growth in data center hot spots, from northern Virginia’s “Data Center Alley,” the world’s densest data center hub, to newer boom markets in Georgia and Texas.

Koomey highlighted one big challenge facing utilities and regulators trying to interpret these forecasts: the significant number of duplicate proposals they contain.

“The data center people are shopping these projects around, and maybe they approach five or more utilities. They’re only going to build one data center,” he explained. “But if all five utilities think that interest is going to lead to a data center, they’re going to build way more capacity than is needed.”

It’s hard to sort out where this “shopping” is happening. Tech companies and data center developers are secretive about these scouting expeditions, and utilities don’t share them with one another or the public at large. National or regional tracking could help, but it doesn’t exist in a publicly available form, Koomey said.

To make things more complicated, local forecasts are also flooded with speculative interconnection requests from developers with land and access to grid power, with or without a solid partnership or agreement in place.

“There isn’t enough power to provide to all of those facilities. But it’s a bit of a gold rush right now,” said Mario Sawaya, a vice president and the global head of data centers and technology at AECOM, a global engineering and construction firm that works with data center developers.

That puts utilities in a tough position. They can overbuild expensive energy infrastructure and risk whiffing on climate goals while burdening customers with unnecessary costs, or underbuild and miss out on a once-in-a-lifetime economic opportunity for them and for their community.

In the face of these risks, some utilities are trying to get better at separating viable projects from speculative ones, a necessity for dealing with the onslaught of new demand.

Utilities and regulators are used to planning for housing developments, factories, and other new electricity customers that take several years to move from concept to reality. A data center using the equivalent of a small city’s power supply can be built in about a year. Meanwhile, major transmission grid projects can take a decade or more to complete, and large power plants take three to five years to move through permitting, approval, procurement, and construction.

Given the mismatch in timescales, “the solution is talking to each other early enough before it becomes a crisis,” said Michelle Blaise, AECOM’s senior vice president of global grid modernization. “Right now we’re managing crises.”

Koomey, Das, and Schmidt highlight work underway on this front in their February report: “Utilities are collecting better data, tightening criteria about how to ‘count’ projects in the pipeline, and assigning probabilities to projects at different stages of development. These changes are welcome and should help reduce uncertainty in forecasts going forward.”

Some utilities are still failing to better screen their load forecasts, however — and tech giants with robust clean energy goals such as Amazon, Google, and Microsoft are speaking up about it. Last year, Microsoft challenged Georgia Power on the grounds that the utility’s approach is “potentially leading to over-forecasting near-term load” and “procuring excessive, carbon-intensive generation” to handle it, partly by including “projects that are still undecided on location.” Microsoft contrasted Georgia Power’s approach to other utilities’ policies of basing forecasts on “known projects that have made various levels of financial commitment.”

Utilities also have incentives to inflate load forecasts. In most parts of the country, they earn guaranteed profits for money spent on power plants, grid expansions, and other capital infrastructure.

As a matter of fact, many utilities have routinely over-forecasted load growth during the past decade, when actual electricity demand has remained flat or increased only modestly. But today’s data center boom represents a different kind of problem, Blaise said — utilities “could build the infrastructure, but not as fast as data centers need it.”

In the face of this gap between what’s being demanded of them and what can be built in time, some utilities are requiring that data centers and other large new customers prove they’re serious by putting skin in the game.

The most prominent efforts on this front are at utility American Electric Power. Over the past year, AEP utilities serving Ohio as well as Indiana and Michigan have proposed new tariffs — rules and rates for utility customers — to deal with the billions of dollars of data center investments now flooding into those states.

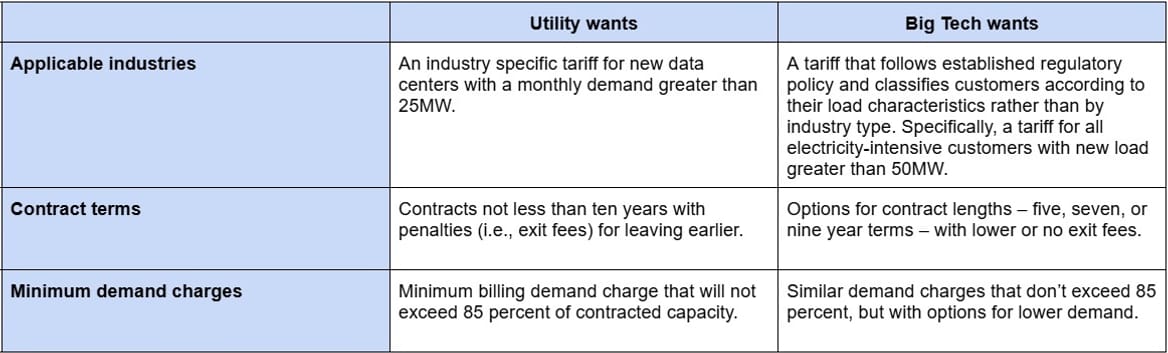

AEP Ohio and state regulators proposed a settlement agreement in October that would require data centers to commit to 12-year agreements to “pay for a minimum of 85% of the energy they say they need each month — even if they use less.” The proposed tariff would also require prospective data center projects to provide more financial disclosures and to pay an exit fee if they back out or fail to meet their commitments.

A counterproposal filed in October by Google, Meta, Microsoft, and other groups would also set minimum power payments but loosen some other requirements.

AECOM’s Sawaya and Katrina Lewis, the company’s vice president and energy advisory director, laid out the differences between the competing proposals in a December opinion piece.

“On the one hand, the utility is seeking to protect other customer classes and reduce unnecessary investment by ensuring longer term commitments,” they wrote. “While on the other, Big Tech is looking to establish tariffs that drive innovation and growth through the appropriate grid investments without individual industries being singled out.”

AEP utility Indiana Michigan Power (I&M) has made more progress than AEP Ohio threading this needle. In November, it reached an agreement with parties including consumer advocates and Amazon Web Services, Google, Microsoft, and the trade group Data Center Coalition. That plan was approved by Indiana utility regulators last week.

A number of nitty-gritty details distinguish that deal from the disputes AEP Ohio is still wrangling over. One key difference is that I&M’s plan would apply to all large power-using customers, not just data centers.

But AECOM’s Lewis noted that data centers aren’t the only stakeholders to consider in making such a plan. Economic-development entities, city and county governments, consumer advocates, environmental groups, and other large energy customers all have their own opinions. Negotiations like those in Ohio and Indiana “will have to happen around the country,” she said. “They’re likely to be messy at first.”

That’s a good description of the various debates happening across the U.S. In Georgia, utility regulators last month approved a new rule requiring data centers of 100 megawatts or larger to pay rates that would include some costs of the grid investments needed to support those centers. But business groups oppose legislative efforts to claw back state sales tax breaks for data centers, including a bill passed last year that Republican Gov. Brian Kemp vetoed.

In Virginia, lawmakers have proposed a raft of bills to regulate data center development, and regulators have launched an investigation into the “issues and risks for electric utilities and their customers.” But Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin has pledged to fight state government efforts to restrain data center growth, as have lawmakers in counties eager for the economic benefits they can bring.

But eventually, Koomey said, these policy debates will have to reckon with a fundamental question about data center expansion: “Who’s going to pay for this? Today the data centers are getting subsidies from the states and the utilities and from their customers’ rates. But at the end of the day, nobody should be paying for this except the data centers.”

Not all data centers bring the same economic — or social — benefits. Policies aimed at forcing developers to prove their bona fides may also need to consider what those data centers do with their power.

Take crypto mining, a business that uses electricity for number-guessing computations to claim ownership of units of digital worth. Department of Energy data suggests that crypto mining represents 0.6% to 2.3% of U.S. electricity consumption, and researchers say global power use for mining bitcoin, the original and most widely traded cryptocurrency, may equal that of countries such as Poland and Argentina.

Crypto mining operations are also risky customers. They can be built as rapidly as developers can connect containers full of servers to the grid and can be removed just as quickly if cheaper power draws them elsewhere.

This puts utilities and regulators in an uncomfortable position, said Abe Silverman, an attorney, energy consultant, and research scholar at Johns Hopkins University who has held senior policy positions at state and federal energy regulators and was a former executive at utility NRG Energy.

“Nobody wants to be seen as the electricity nanny — ‘You get electricity, you don’t,’” he said. At the same time, “we have to be careful about saying utilities have to serve all customers without taking a step back and asking, is that really true?”

Taking aim at individual customer classes is legally tricky.

In North Dakota, member-owned utility Basin Electric Cooperative asked the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for permission to charge crypto miners more than other large customers to reduce the risk that gigawatts of new “highly speculative” crypto load could fail to materialize. Crypto operators protested, and FERC denied the request in August, saying that the co-op had failed to justify the change but adding that it was “sympathetic” to the co-op’s plight.

Silverman noted that AEP Ohio’s proposed tariff also sets more stringent collateral requirements on crypto miners than on other data centers. That has drawn opposition from the Ohio Blockchain Council, a crypto trade group, which joined tech companies in the counterproposal to the proposed tariff.

It’s likely that the industry, boosted by its influence with the crypto-friendly Trump administration, will challenge these kinds of policies elsewhere.

Then there’s AI, the primary cause of the dramatic escalation of data center load forecasts over the past two years. In their report, Koomey, Das, and Schmidt take particular aim at forecasts from “influential management consulting and investment advising firms,” which, in Koomey’s view, have failed to consider the physical and financial limitations to unchecked AI expansion.

Such forecasts include those from McKinsey, which has predicted trillions of dollars of near-term economic gains from AI, and from Boston Consulting Group, which proposes that data centers could use as much power as two-thirds of all U.S. households by 2030.

But these forecasts rely on “taking some recent growth rate and extrapolating it into the future. That can be accurate, but it’s often not,” Koomey said. These consultancies also make money selling services to companies, which incentivizes them to inflate future prospects to drum up business. “You get attention when you make aggressive forecasts,” he said.

Good forecasts also must consider hard limits to growth. Koomey helped research December’s “2024 United States Data Center Energy Usage Report” from DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which used real-world data on shipments and orders of the graphical processing units (GPUs) used by AI operations today, as well as forecasts of how much more energy-efficient those GPUs could become.

That forecast found data centers are likely to use from 6.7% to 12% of total U.S. electricity by 2028, up from about 4.4% today.

To be clear, those numbers contain an enormous range of uncertainty, and nationwide estimates don’t help individual utilities or regulators figure out what may or may not get built in their territories. Still, “we think this is a pretty reliable estimate of what energy demand growth is going to look like from the sector,” said Avi Shultz, director of DOE’s Industrial Efficiency and Decarbonization Office. “Even at the low end of what we expect, we think this is very real.”

Koomey remains skeptical of many current high forecasts, however. For one, he fears they may be discounting the potential for AI data centers to become far more energy-efficient as processors improve — something that has happened reliably throughout the history of computing. Similar mistakes informed wild overestimates of how much power the internet was going to consume back in the 1990s, he noted.

“This all happened during the dot-com era,” when “I was debunking this nonsense that IT [information technology] would be using half of the electricity in 10 years.” Instead, data centers were using only between 1% and 2% of U.S. electricity as of 2020 or so, he said. The DeepSeek news indicates that AI may be in the midst of its own iterative computing-efficiency improvement cycle that will upend current forecasts.

Speaking of the dot-com era, there’s another key factor that today’s load growth projections fail to take into account — the chance that the current AI boom could end up a bust. A growing number of industry experts question whether today’s generative AI applications can really earn back the hundreds of billions of dollars that tech giants are pouring into them. Even Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella spoke last week about an “overbuild” of AI systems.

“Over the next several years alone, we’re going to spend over a trillion dollars developing AI,” Jim Covello, head of stock research at investment firm Goldman Sachs, said in a discussion last year with Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor and Nobel Prize–winning economist Daron Acemoglu. “What trillion-dollar problem is AI going to solve?”

In part 3 of this series, Canary Media reports on how to build data centers that won’t make the grid dirtier.