Plans are in the works to build America’s first new aluminum smelters in nearly half a century. The two facilities, slated to go online in Oklahoma and possibly Kentucky in the coming years, would dramatically boost domestic production of the versatile metal if completed as planned.

But for that to happen, they will first have to secure a steady supply of electricity, at a time when AI data centers and other industrial facilities are competing fiercely for a share of the country’s limited power resources, and as the grid is strained by surging demand.

The smelters proposed by Emirates Global Aluminium and Century Aluminum would be energy hogs. Each plant is expected to produce about 600,000 metric tons of aluminum each year, requiring enough electricity annually to power the state of Rhode Island. That’s because the process of converting raw materials into primary aluminum requires hundreds of megawatts of power running at near-constant rates.

For the economics to pencil out for either facility, that power will need to be cheap. And it will need to be produced from carbon-free sources, like wind or solar, for the aluminum they produce to be more competitive on the global market, which increasingly favors low-carbon metal.

Unfortunately for American aluminum producers, both clean and affordable power are only getting harder to come by.

Electricity demand in the U.S. is rising faster than supply is forecast to grow, which is pushing up prices. Aging grid infrastructure and slow permitting timelines have long delayed the build-out of new power generation. Now the Trump administration and GOP-led Congress are creating additional financial and legal headwinds for wind, solar, and battery storage projects — the only resources that can be built fast enough to meet demand in the near term.

“With clean energy tax credits going away, we can reasonably expect the cost of electricity to go up in all markets,” said Annie Sartor, the aluminum campaign director for Industrious Labs, an advocacy organization. “That’s just profoundly challenging to aluminum facilities that are looking for electricity … especially in a moment when there’s a rush on electricity nationally.”

The deepening power crunch represents a major roadblock in the quest to reshore U.S. manufacturing.

The Trump administration recently raised tariffs on aluminum and steel imports from 25% to 50% to bolster the business case for producing primary metals domestically. It has also preserved a crucial award for Century Aluminum’s smelter that was issued in the final days of the Biden administration. In January, the Department of Energy awarded Century a grant of up to $500 million as part of a federal industrial decarbonization program, much of which has since been defunded.

But to successfully kick-start an American aluminum renaissance, the government and utilities will also need to make larger long-term investments in the nation’s ailing electricity sector, and develop tools that allow smelters to not just take power from the grid, but to help it run more smoothly, experts say.

“Ultimately, this is about energy,” said Matt Meenan, vice president of external affairs for the Aluminum Association, a trade group that supports an “all-of-the-above” approach to electricity sources.

“And until you crack that nut,” he added, “I think we’re going to have a hard time becoming fully self-sufficient for primary aluminum in the U.S.”

Aluminum companies worldwide produced 73 million metric tons of primary, or virgin, aluminum in 2024. The lightweight metal is used to make products as varied as fighter jets, power cables, soda cans, and deodorant. It’s also a key component of clean energy technologies like electric vehicles, solar panels, and heat pumps.

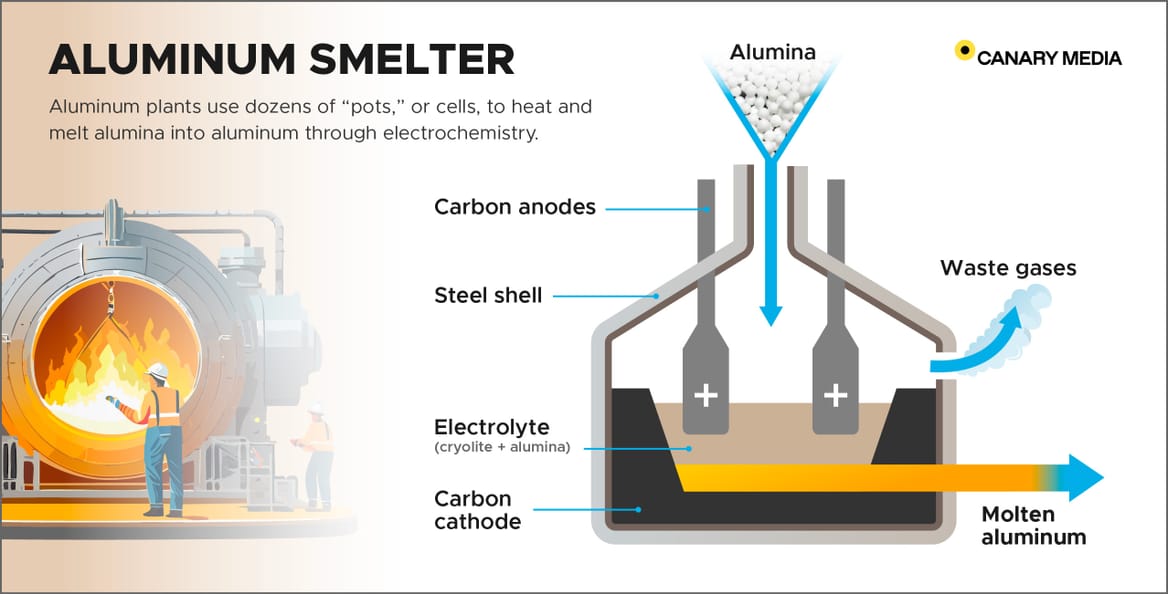

Producing aluminum contributes about 2% of total greenhouse gas emissions every year. The majority of those emissions come from generating high volumes of electricity — often derived from fossil fuels — to power smelters. The smelting process involves dissolving powdery white alumina in a scorching-hot salt bath, then zapping it with electrical currents to remove oxygen molecules and make aluminum.

The United States was once one of the world’s top producers of primary aluminum. In 1980 — the last year a new smelter was built — the nation had 33 operating facilities, many of which relied on cheap power from public hydropower plants. But then industrial electricity rates began to rise after the federal government restructured energy markets in 1977.

Deregulation was “the single most important factor leading to the near total demise of the primary aluminum industry,” the Aluminum Association said in a recent white paper entitled “Powering Up American Aluminum.” The U.S. industry’s downward spiral accelerated further after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, leading to a glut of inexpensive Chinese aluminum on the global market.

Today, just four American smelters remain operational. In 2024, they produced an estimated 670,000 metric tons of primary aluminum, or less than 1% of global production. The U.S. mainly makes secondary aluminum from scrap metal, which totaled over 5 million metric tons last year. While secondary production is growing, it can’t fully replace the need for strong and durable primary aluminum.

“There’s always going to be a role for primary aluminum,” Meenan said. “And we do think having smelters here is really important.”

Century Aluminum and Emirates Global Aluminium both say their new smelters will mark a new beginning for the U.S. primary-aluminum sector. The two facilities would together nearly triple the nation’s primary-aluminum capacity when they come online, potentially around 2030.

Century Aluminum first unveiled plans for its smelter in March 2024, after the Biden-era Department of Energy launched a $6 billion initiative to modernize and decarbonize America’s industrial base. As part of the award process, Century said its Green Aluminum Smelter could run on 100% renewable or nuclear energy and would use energy-efficient designs, making it 75% less carbon-intensive than traditional smelters.

At the time, the Chicago-based manufacturer identified northeastern Kentucky as its preferred location for the smelter, though the company was also evaluating sites in the Ohio and Mississippi river basins. More than a year later, Century still hasn’t picked a final project site for the $5 billion smelter — because it hasn’t yet locked down its power supply.

Electricity isn’t available at the fixed long-term price that smelters need to ensure profitability and pay back billions of dollars in construction costs, Matt Aboud, Century’s senior vice president of strategy and business development, said in May at a global aluminum summit in London, Reuters reported.

“We remain really excited about the project,” Jesse Gary, Century’s president and CEO, said on a May 7 earnings call. “The next two key milestones are to finalize negotiations of the power arrangements, and then following from that … we’ll be making a site selection.”

The Aluminum Association estimates that manufacturers would need a 20-year power contract at or below $40 per megawatt-hour to justify investing in a new smelter at today’s aluminum prices. Restarting the nation’s fleet of idled smelters, which represent 601,500 metric tons in primary capacity, would require a similar arrangement.

Currently, power-purchase agreements for U.S. renewable energy projects are in the range of $50 to $60 per MWh — a significant difference for these power-hungry facilities. Tech giants like Microsoft have signaled their willingness to pay north of $100 per MWh for electricity from nuclear and fossil-gas plants to fuel their data centers, giving those firms an advantage over price-sensitive buyers in the race for electricity.

Meanwhile, in Oklahoma, Emirates Global Aluminium is advancing its $4 billion smelter project with the promise of significant financial support from taxpayers and utility customers.

The Abu Dhabi-based conglomerate in May signed a nonbinding agreement to build the smelter with the office of Republican Gov. J. Kevin Stitt, a deal that includes over $275 million in incentives, including discounts for power. The manufacturer and governor’s office are working to establish a “special rate offer” from the Public Service Co. of Oklahoma — a subsidiary of utility giant AEP — for the new facility.

Simon Buerk, EGA’s senior vice president for corporate affairs, said that Oklahoma’s “energy abundance” was a key factor in selecting the state for the new aluminum smelter.

More than 40% of Oklahoma’s annual electricity generation comes from wind turbines spinning on open prairies, while about half the state’s generation comes from fossil-gas power plants. Last month, the Public Service Co. acquired an existing 795-MW gas plant just south of Tulsa to meet the rising energy needs of its customers, including potentially EGA.

Buerk said EGA and the utility are in “advanced negotiations” to finalize a competitive power contract. One option the groups are considering is a tariff structure that gives the smelter dedicated long-term access to a proportion of renewable energy, equal to 40% of the smelter’s needs. The smelter’s annual power mix “will be based on EGA’s decarbonisation objectives, market dynamics, and market demand for low-carbon aluminum,” he said by email.

Outside the United States, nearly all primary aluminum smelters receive some form of government backing in the countries where they operate — typically by ensuring access to affordable energy, said Sartor of Industrious Labs.

She pointed to Canada, the largest supplier of U.S. aluminum imports. Smelters in Quebec draw from the region’s abundant hydropower resources, which are operated by the government-owned entity Hydro-Quebec. The price of electricity that producers pay is often tied to the price of aluminum on commodities markets, so that smelters pay less during lean times and more when the market recovers.

“The industry functions through government support all over the world, and we should be looking at those models and finding one that fits us here,” said Sartor.

Manufacturers and utilities can also structure power-supply agreements that enable smelters to benefit, rather than strain, the grid, said Anna Johnson, a senior researcher in the industry program at the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy.

“When we think about how to address the challenge of procuring large amounts of clean power, one of the first tools we think about is, what can we do on the demand side to mitigate that load and make sure that the demand of these facilities is avoiding times of peak stress?” she said.

In New Zealand, for example, Rio Tinto’s Tiwai Point smelter receives financial incentives to curb its electricity use — and therefore lower its aluminum production — during dry seasons, when hydropower resources can become critically low. In Australia, the aluminum giant Alcoa is participating in a program that turns one of its smelters into an emergency resource when the grid is overly stressed. The Australian government pays Alcoa to halt production on some of its aluminum-making potlines for about an hour at a time.

In the U.S., other types of industrial plants — including a titanium-melting plant in West Virginia — are using behind-the-meter solar power and battery storage systems, so that the facilities are primarily drawing from the electrical grid only during off-peak hours.

Strategies like these that reduce electricity rates are especially crucial now that the development of cheap, renewable energy is set to slow in the United States. But manufacturers will still need access to new carbon-free electricity sources in order to produce the cleaner aluminum that customers are increasingly demanding, Sartor said.

“When [companies] build a new facility, they’re building it for 50 or 100 years,” she said. Even as the Trump administration winds back the clock on U.S. climate action, smelters “need to find clean power as a matter of international competitiveness.”