The highest court of the UN has issued a landmark “advisory opinion” stating that nations can be held legally accountable for their greenhouse-gas emissions.

Recognising the “urgent and existential threat” facing the world, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) concluded that those harmed by human-caused climate change may be entitled to “reparations”.

Their opinion largely rests on the application of existing international law, clarifying that climate “harms” can be clearly linked to major emitters and fossil-fuel producers.

The case, which was triggered by a group of Pacific island students and championed by the government of Vanuatu, saw unprecedented levels of input from nations.

In a unanimous decision issued on 23 July, the 15 judges on the ICJ concluded that the production and consumption of fossil fuels “may constitute an internationally wrongful act attributable to that state”.

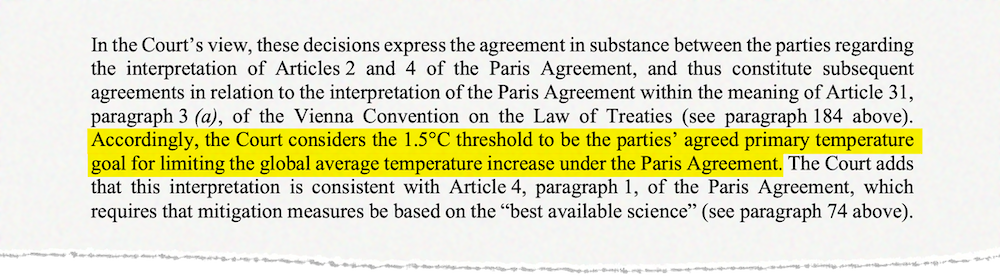

The opinion also says that limiting global warming to 1.5C should be considered the “primary temperature goal” for nations and, to achieve it, they are obliged to make “adequate contributions”.

While the ICJ opinion is not binding for governments, it could have significant influence as vulnerable groups and nations push for stronger climate action or seek compensation in court.

Below, Carbon Brief explains the most important aspects of the ICJ’s 133-page advisory opinion and speaks to legal experts about its implications.

The case stems from a campaign led by 27 students from the University of the South Pacific in Fiji.

In 2019, they established a youth-led grassroots organisation – dubbed the Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change (PISFCC) – and began efforts to persuade the leaders of the Pacific Islands Forum to take the issue of climate change to the world’s top court.

PISFCC joined forces with other youth organisations from around the world in 2020, lobbying state representatives to take action.

In 2021, the government of Vanuatu announced that it would lead efforts to gain an “advisory opinion” from the ICJ. It worked to engage with the Pacific island community first, to build a “coalition of like-minded vulnerable countries”, reported Climate Home News.

Following on from this work, Vanuatu received a unanimous endorsement for its efforts from the 18 members of the Pacific Island Forum. It continued to work diplomatically, engaging in discussions across Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America to encourage other countries to join the effort.

After three rounds of consultations with other states, the resolution was put before the UN general assembly with the backing of 105 sponsor countries.

Finally, on 29 March 2023, the assembly unanimously adopted the resolution formally requesting an “advisory opinion” from the ICJ.

The resolution posed two questions for the ICJ. In answering these questions, it asked the court to have “particular regard” to a range of laws and principles, including the UN climate regime and the universal declaration on human rights.

First, the resolution asked what are the legal obligations of states under international law to “ensure the protection of the climate system”.

Second, it asked what are the legal consequences flowing from these obligations if states, by their “acts or omissions”, have caused “significant harm to the climate”.

The resolution asked for the court to consider, in particular, states that are “specially affected” or are “particularly vulnerable” to the impacts of climate change.

It also pointed to “peoples and individuals of the present and future generations affected by the adverse effects of climate change”.

Therefore, the advisory opinion issued this week by the ICJ, in response to these questions, is the culmination of a years-long process.

Although the opinion is not binding on states, it is binding on UN bodies and is likely to have far-reaching legal and political consequences at a national level.

The ICJ was tasked with interpreting international law and arriving at an advisory opinion. While its legal advice will, therefore, not be binding for nations, it will be binding for other UN bodies.

This two-year process involved the judges defining the scope and meaning of the broad questions put to them by the UN general assembly. (See: How did the case come about?)

They then considered which international laws and principles were relevant for these questions.

Among the relevant laws identified were the three UN climate change treaties – the UNFCCC, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement.

They also considered various other treaties covering biodiversity, ozone depletion, desertification and the oceans, as well as legal principles such as the principle of “prevention of significant harm to the environment”.

The ICJ’s process has also seen nations and international groups, such as the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec), offer their views on the case.

These groups had the opportunity to feed into the judges’ deliberations over several stages, including two sets of written submissions, followed by oral statements to the court.

In total, the court received 91 written statements, a further 107 oral statements – delivered at the Hague in December 2024 – and 65 responses to follow-up questions by the judges.

This is the “highest level of participation in a proceeding” in the court’s history, according to the ICJ. Some nations, including island states such as Barbados and Micronesia, appeared before the court for the first time ever.

These contributions demonstrated broad agreement among nations that climate change is a threat and that emissions should be cut in order to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

But there were major divergences on the breadth and nature of obligations under international law to act to limit global warming, as well as on the consequences of any breaches, as specifically being addressed by the ICJ.

Overall, the main divisions were between high-emitting nations trying to limit their climate obligations and low-emitting, climate-vulnerable nations, who were pushing for broader legal obligations and stricter accountability for any breaches.

Specifically, “emerging” economies such as China and Saudi Arabia, along with historical high-emitters such as the UK and EU, argued that climate obligations under international law should be defined solely by reference to the UN climate regime.

In contrast, vulnerable nations said that wider international law should also apply, bringing additional obligations to act – and the potential for legal consequences, including reparations.

This is a departure from UN climate talks, where the main divide tends to be between “developed” and “developing” countries – with the latter encompassing both high- and low-emitting nations.

In an unusual move, the ICJ judges also organised a private meeting in November 2024 with scientists representing the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Among those present were IPCC chair Prof Jim Skea and eight other climate scientists from various countries and with different areas of expertise.

A statement issued by the ICJ said this was an effort to “enhance the court’s understanding of the key scientific findings which the IPCC has delivered”.

On 23 July 2025, after some seven months of deliberation, the ICJ issued a unanimous opinion in response to the UN general assembly’s request.

This is only the fifth time the court has delivered a unanimous result, according to the ICJ, after nearly 88 years in operation and 29 opinions.

(In addition to the unanimous opinion of the full court, several of the ICJ judges also issued their own declarations and opinions, individually or in small groups.)

When considering the “context” for the issuing of the advisory opinion on climate change, the court provides information on the “relevant scientific background”.

This was drawn from reports by the IPCC, which the court says “constitute the best available science on the causes, nature and consequences of climate change”.

It comes after ICJ judges held a private meeting with IPCC scientists in 2024. (See: How has the case been decided?)

The advisory opinion states that it is “scientifically established that the climate system has undergone widespread and rapid changes”, continuing:

“While certain greenhouse gases [GHGs] occur naturally, it is scientifically established that the increase in concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere is primarily due to human activities, whether as a result of GHG emissions, including by the burning of fossil fuels, or as a result of the weakening or destruction of carbon reservoirs and sinks, such as forests and the ocean, which store or remove GHGs from the atmosphere.”

It continues that the “consequences of climate change are severe and far-reaching”, listing impacts including the “melting of ice sheets and glaciers, leading to sea level rise”, “more frequent and intense” extreme weather events and the “irreversible loss of biodiversity”. The document adds:

“These consequences underscore the urgent and existential threat posed by climate change.”

The advisory opinion further adds that the “IPCC notes that adaptation measures are still insufficient” and that “limits to adaptation have been reached in some ecosystems and regions”.

On the need to address rising emissions, the document quotes the IPCC directly, saying:

“According to the panel, climate change is a threat to ‘human well-being and planetary health’ and there is a ‘rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all’ (very high confidence). It adds that the choices and actions implemented between 2020 and 2030 ‘will have impacts now and for thousands of years’.”

It adds that the “IPCC has also concluded with ‘very high confidence’ that risks and projected adverse impacts and related loss and damage from climate change will escalate with every increment of global warming”.

In regards to how states should consider climate science when implementing climate policies and measures, the court says that countries should exercise the “precautionary principle”, adding:

“The court observes that where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.”

In response to the first question on legal obligations, the ICJ says that countries have “binding obligations to ensure protection of the climate system” under the UN climate treaties.

However, the court’s unanimous opinion flatly rejects the argument, put forward by high emitters, such as the US, UK and China, that these treaties are the end of the matter.

These nations had argued that the climate treaties formed a “lex specialis”, a specific area of law that precludes the application of broader general international law principles.

On the contrary, the ICJ says countries do have legal obligations under general international law, including a duty to prevent “significant harm to the environment”, with further obligations arising under human rights law and from other treaties.

As such, the court, “essentially sided with the global south and small island developing states”, says Prof Jorge Viñuales, Harold Samuel professor of law and environmental policy at the University of Cambridge.

Moreover, the court finds that countries’ obligations extend not only to greenhouse gas emissions, but also to fossil-fuel production and subsidies, says Viñuales, who acted for Vanuatu in the case.

Speaking to Carbon Brief in a personal capacity, he says: “That is important because major producers are not necessarily major emitters and vice-versa.”

In terms of the UN climate treaties, such as the Paris Agreement, the court affirms that these give countries binding obligations including adopting measures to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change.

Developed countries – parties listed under Annex I of the UNFCCC – have “additional obligations to take the lead in combating climate change”, the ICJ notes.

States also have a “duty” to cooperate with each other in order to achieve the objectives of the UNFCCC, acting in “good faith” to prevent harm, it adds.

Beyond the climate treaties, it says that “states have a duty to prevent significant harm to the environment”. Therefore, they must act with “due diligence” and use “all means at their disposal” to prevent activities carried out within their jurisdiction or control from causing “significant harm” to the climate system.

The court sets out the “appropriate measures” that would demonstrate due diligence, including “regulatory mechanisms…designed to achieve deep, rapid and sustained reductions” in emissions. This repeats language from the IPCC, but attaches it to countries’ legal obligations.

As with action under the climate treaties, countries’ obligations under broader international law should be taken in accordance with the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” it adds, a point reaffirmed throughout the advisory opinion.

Furthermore, countries have obligations to act on climate under a raft of other international agreements, covering the ozone layer, biological diversity, desertification and the UN convention on the law of the sea, the ICJ notes.

The court affirms that states that are not party to UN climate treaties must still meet their equivalent obligations under customary international law. This “addresses the unique situation of the US, but without naming it”, notes Sébastien Duyck, a senior attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law, on Bluesky.

Following his re-election last year, US president Donald Trump signed an order to pull the country out of the Paris Agreement again. As such, there is a question around how the ICJ’s opinion might apply to the US – the country that has contributed more to human-caused climate change than any other nation.

Additionally, states have obligations under international human rights law to “respect and ensure the effective enjoyment of human rights by taking necessary measures to protect the climate system and other parts of the environment”, according to the ICJ.

This follows a ruling from the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in 2024 that found that the Swiss government’s climate policies violated human rights, as governments are obliged to protect citizens from the “serious adverse effects” of climate change.

Announcing the opinion to the Hague, judge Iwasawa Yuji, president of the court, said:

“The human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is essential for the enjoyment of other human rights.”

The second part of the advisory opinion deals with the “legal consequences” of countries causing “significant harm to the climate system and other parts of the environment”.

This refers to nations breaching their “obligations”, as defined in the first part of the opinion. (See: What does the ICJ say about countries’ climate obligations?)

Crucially, the court says that countries can, in principle, face liability for climate harms, opening the door to potential “reparations” for loss and damage. Prof Viñuales tells Carbon Brief:

“Perhaps the main take away from the opinion is that the court recognised the principle of liability for climate harm, as actionable under the existing rules.”

Prof Viñuales notes that the court says “climate justice is governed by the general international law of state responsibility, which provides solutions for the recurrent arguments levelled to escape liability for climate harm”.

Essentially, the ICJ rejects the notion that it is too difficult to hold countries accountable for climate damages.

Examples of breached obligations given by the court include failing to set out or implement climate pledges – known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs) – under the Paris Agreement, or to sufficiently “regulate emissions of greenhouse gases”.

The ICJ stresses that it is not responsible for pointing fingers at particular countries, only for issuing a “general legal framework” that countries can follow.

As part of this process, it lays out a justification for why states can be held responsible for climate change.

During the ICJ process, some countries argued that greenhouse gas emissions are not like other environmental damage, such as localised chemical pollution. They said that emissions arise from all sorts of regular activities and it is difficult to tie climate damage to specific sources.

Others argued that it is perfectly possible to attribute such damage to states that, for example, have laws to “promote fossil-fuel production and consumption”.

This is important, as the ICJ points out that attribution is necessary if an activity is to be defined as an “internationally wrongful act”. Ultimately, the court agrees that it is feasible to attribute climate damage to specific states, on a “case-by-case” basis.

The court also finds that it is possible, at least in principle, to link climate disasters to countries’ emissions, though it notes that the causal links may be “more tenuous” than for localised pollution. It cites IPCC findings that climate change has amplified heatwaves, flooding and drought, stating:

“While the causal link between the wrongful actions or omissions of a state and the harm arising from climate change is more tenuous than in the case of local sources of pollution, this does not mean that the identification of a causal link is impossible.”

With this established, the court sets out what the consequences could be for countries that are deemed to have carried out “wrongful acts”.

First, the ICJ stresses that nations must meet their existing climate obligations. This means that if, for example, a government publishes an “inadequate” NDC, a “competent court or tribunal” could order it to supply one that is consistent with its obligations under the Paris Agreement.

Second, it also says that if a state is found responsible for climate damage, it must stop and ensure that it does not happen again.

States may be required to “employ all means at their disposal” to carry out this duty, according to the ICJ. In practice, the court says that this could mean governments revoking administrative or legislative acts in order to cut emissions.

In theory, this could lead to more stringent climate policies. For example, Dr Maria Antonia Tigre, director of global climate change litigation at the Sabin Centre for Climate Change Law, tells Carbon Brief:

“The ICJ made clear that the standard of due diligence is stringent and that each state must do its utmost to submit NDCs reflecting its highest possible ambition. That may strengthen pressure – political, legal and public – on states to raise their climate targets, especially before the next global stocktake.”

Finally, the ICJ opens the door for countries to seek “reparations” for climate harms from other countries.

It says these reparations could be expressed in different ways – including paying compensation or issuing formal apologies for wrongdoing.

This outcome was widely celebrated by climate justice activists and vulnerable nations, who see it as ushering in a “new era” in the fight to obtain financial compensation for climate disasters.

Harj Narulla, a barrister at Doughty Street Chambers and legal counsel for the Solomon Islands, tells Carbon Brief:

“The ICJ’s ruling has provided a legal pathway for developing states to seek climate reparations from developed States…States can bring claims for compensation or restitution for all climate-related damage. This includes claims for loss and damage, but importantly extends to any harm suffered as a result of climate change.”

One of the most significant parts of the ICJ opinion is the assertion that nations and “injured individuals” can seek “reparations” for climate damage.

This ties in with a long and contentious history of climate-vulnerable nations in the global south seeking compensation from high-emitting nations.

The notion of “climate reparations” has often been linked to developing countries pushing for so-called “loss and damage” finance in UN climate negotiations, including the – ultimately successful – fight for a “loss-and-damage fund”.

However, the US and other big historical emitters have ensured that any progress on loss-and-damage funding has not left them legally accountable for their past emissions.

The Paris Agreement states explicitly that its inclusion of loss and damage “does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation”.

Crucially, the ICJ opinion makes it clear that such language does not override international law and states’ responsibilities to provide “restitution”, “compensation” and “satisfaction” to those harmed by climate change.

Danilo Garrido Alves, a legal counsel for Greenpeace International, tells Carbon Brief that this means loss-and-damage finance is not a replacement for reparations:

“If a state contributes to the loss and damage fund and at the same time breaches obligations…that does not mean they are off the hook.”

Legal experts, including Prof Viñuales, tell Carbon Brief that this outcome is not surprising, given its grounding in international law. He says:

“It is the correct understanding of international law, but, in law, progress often takes the form of moving from the implicit to the explicit and that’s what the court did.”

Nevertheless, the outcome could have major implications for climate politics and lead to a wave of new climate litigation. Dr Tigre, at the Sabin Centre for Climate Change Law, tells Carbon Brief:

“[It] could shift the conversation from voluntary climate finance to legal obligations to repair harm, particularly for vulnerable communities and states already suffering loss and damage.”

Notably, the court says that while some states are “particularly vulnerable” to climate change, international law “does not differ” depending on such status. This means that, in principle, all nations are “entitled to the same remedies”.

As for individuals or groups taking legal action for both “present and future generations”, the ICJ notes that their ability to do so does not depend on rules around “state responsibility”. Instead, they would depend on obligations being breached under “specific treaties and other legal instruments”.

The ICJ says that reparations would be determined on a case-by-case basis, noting that the “appropriate nature and quantum of reparations…depends on the circumstances”. It also notes that:

“In the climate change context, reparations in the form of compensation may be difficult to calculate, as there is usually a degree of uncertainty.”

The question of precisely which nations will be liable for paying climate reparations is also predictably complex. Much of this discussion centres around responsibility for emissions, both currently and in the past.

Under the Paris Agreement, “developed” countries – a handful of nations in the global north – are obliged to provide climate finance to “developing” countries, which includes major emitters such as China.

In ICJ submissions, major emitters and fossil-fuel producers categorised as “developing” under the UN system stressed their low historical emissions. Some developing countries blamed climate change on a small group of “developed states of the global north”.

For their part, some countries with high historical emissions argued that it is difficult to assign responsibility for climate change.

However, the ICJ concludes that this is not the case. It says it is “scientifically possible” to determine each state’s contribution, accounting for “both historical and current emissions”.

Therefore, while the court explicitly avoids identifying the countries responsible for paying reparations, it makes clear that historical responsibility should be accounted for when considering whether states have met their climate obligations.

Finally, the court also says that “the status of a state as developed or developing is not static” and that it depends on the “current circumstances of the state concerned”.

This is notable, given that the current definitions of these terms – which determine who gives and receives climate finance – are based on definitions from the early 1990s.

The advisory opinion offers clear guidance on the Paris Agreement and its aim to limit global temperature rise to “well-below” 2C by 2100, with an aspiration to keep warming below 1.5C.

It says that limiting temperature increase to 1.5C should be considered countries’ “primary temperature goal”, based on the court’s interpretation of the Paris Agreement.

The court adds that this interpretation is consistent with the Paris Agreement’s stipulation that efforts to tackle climate change should be based on the “best available science”.

(In 2018, four years after the Paris Agreement, a special report from the IPCC spelled out how limiting global warming to 1.5C rather than 2C could, among other things, save coral reefs from total devastation, stem rapid glacier loss and keep an extra 420 million people from being exposed to extreme heatwaves.)

Following this, the advisory opinion also makes it clear that countries are not just encouraged – but “obliged” – to put forward climate plans that “reflect the[ir] highest possible ambition” to make an “adequate contribution” to limiting global warming to 1.5C.

(The climate plans that countries submit to the UN under the Paris Agreement are known as “nationally determined contributions” or “NDCs”.)

Moreover, contrary to the arguments of some countries, the advisory opinion states:

“The court considers that the discretion of parties in the preparation of their NDCs is limited.

“As such, in the exercise of their discretion, parties are obliged to exercise due diligence and ensure that their NDCs fulfil their obligations under the Paris Agreement and, thus, when taken together, are capable of achieving the temperature goal of limiting global warming to 1.5C.”

Dr Bill Hare, a veteran climate scientist and CEO of research group Climate Analytics, noted that the court’s stipulations on the 1.5C and NDCs represent a “fundamental set of findings”. In a statement, he said:

“The ICJ finds that the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit is the primary goal because of the urgent and existential threat of climate change and that this requires all countries to work together towards the highest possible ambition to limit warming to this level.

“All countries have an obligation to put forward the highest possible ambition in their NDCs that represent a progression over previous NDCs; it is not acceptable to put forward a weak NDC that does not align with 1.5C.

“The ICJ points to potential for serious legal consequences under customary international law if countries do not put forward targets aligned to 1.5C.”

The court also notes that the concept of equity is essential to the Paris Agreement and other climate legal frameworks, commonly referred to by text noting that countries have “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities”.

Significantly, it adds that the Paris Agreement differs from other climate frameworks by also stating that these responsibilities and capabilities should be considered “in the light of different national circumstances”.

The advisory opinion continues:

“In the view of the court, the additional phrase does not change the core of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities; rather, it adds nuance to the principle by recognising that the status of a state as developed or developing is not static. It depends on an assessment of the current circumstances of the state concerned.”

The verdict comes after debate – considered highly controversial by many – about whether “emerging” economies, such as China and India, should be considered “developing countries” at climate summits.

One of the most eye-catching paragraphs of the advisory opinion relates to its verdict on fossil fuels.

In a section labelled “determination of state responsibility in the climate change context”, the court specifically addresses countries’ obligations when it comes to producing, using and economically supporting fossil fuels. (See below).

The court says that fossil-fuel production, consumption, the granting of exploration licences or the provision of subsidies “may constitute an internationally wrongful act” attributable to the state or states involved.

It comes after multiple analyses have concluded that any new oil and gas projects globally would be “incompatible” with limiting global warming to 1.5C.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, climate law expert Prof Jorge Viñuales notes that the clear mention of fossil fuels comes despite not being featured in the questions posed to the court:

“The request characterised the conduct to be assessed by reference to emissions, so the court could have stayed there. Yet, the relevant conduct was expanded to production and consumption of fossil fuels, including subsidies.”

Though the advisory opinion is not legally binding on countries, it could influence domestic decision-making around granting permissions to new fossil fuel projects going forward, adds Joy Reyes, a policy officer at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Litigants can cite the advisory opinion in future climate litigation, which includes the language around fossil fuels. While not legally binding, the advisory opinion carries moral weight and authority, and can influence domestic decision-making around new fossil-fuel projects. If states and corporations fail to transition away from fossil fuels, their risk for liability increases.”

The ICJ’s advisory opinion concludes that nations’ existing maritime zones or statehood would “not necessarily” be compromised by sea-level rise resulting from climate change.

This has long been an important issue for island nations, including the Pacific states that pushed for the court’s advisory opinion (See: How did this case come about?).

Some of these nations are very low-lying and are already making preparations for a time when much of their territory is underwater.

They have been seeking assurances that they will retain territorial rights as the impacts of climate change worsen.

In its assessment of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the ICJ says that nations are “under no obligation to update charts or lists of geographical co-ordinates” due to sea-level rise.

This means the legal rights of states over their maritime zones – including any resources, such as minerals and fish, that are present there – would be protected.

The ICJ also states that, in its view:

“Once a state is established, the disappearance of one of its constituent elements would not necessarily entail the loss of its statehood.”

Prof Viñuales, who acted for the island nation of Vanuatu in the case, tells Carbon Brief this outcome is a “key aspect” of the opinion, adding that it is “remarkable”.

Following the landmark advisory opinion, one of the biggest questions moving forward is what it could mean for other climate lawsuits, both domestic and international.

Advisory opinions from the ICJ are not legally binding, but the court’s summarisation of existing law carries “moral weight and authority”, according to Joy Reyes, a policy officer at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

This is particularly relevant for states that “accept the persuasive authority of international law”, explains Dr Joana Setzer, an environmental lawyer and an associate professorial research fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science’s Grantham Institute.

Courts in some states, such as the UK, Australia and Canada, will consult international law when interpreting domestic laws or dealing with international treaties.

Setzer explains to Carbon Brief:

“The ICJ confirms that failures to act – such as maintaining inadequate national targets, licensing new fossil fuel projects or failing to support adaptation in vulnerable countries – can engage state responsibility under international law. The court also dismissed a common defence – that a state’s emissions are ‘too small to matter’. Even small contributors can be held responsible for their share of the harm.

“Domestic climate litigation may seek to use this argument and the court’s opinion to establish greater obligation on states to address climate change at the domestic level. Courts in jurisdictions that accept the persuasive authority of international law, such as the Netherlands, could now cite this ruling in support of decisions compelling stronger climate action from governments or corporations.”

She adds that the court’s conclusion that “states are not only responsible for reducing their own emissions”, but “also have a due diligence duty to regulate private actors under their jurisdiction” could have implications. Stezer continues:

“That includes fossil-fuel companies. This has far-reaching implications: it signals that states could be in breach if they fail to control emissions from companies they license, subsidise or oversee. This will place greater pressure on states to halt any new fossil fuel projects and introduce stricter regulations on the sector.”

Climate law expert Prof Jorge Viñuales says that the opinion makes it clear that the Paris Agreement is a “serious legal instrument imposing genuine and justiciable obligations”, which is likely to have an impact on domestic lawsuits. He tells Carbon Brief:

“We can expect that to be widely litigated around the world.”

In addition, he says that the court’s opinion that countries’ legal obligations extend beyond the UN climate treaties creates a “much wider chessboard for climate litigation”. He adds:

“Last, but absolutely not least, it was important, from a climate justice perspective, to hear from the court that one cannot simply game the climate change regime without legal consequences. Those consequences may take time to materialise, but they very likely will.”

The ICJ’s advisory opinion was welcomed by many governments, NGOs and legal experts as a “groundbreaking” legal milestone and a “moral reckoning”.

However, the European Commission and France were among those responding to the court’s opinion more cautiously, while opposition politicians in the UK were hostile to the ICJ’s findings.

A Chinese government spokesperson, meanwhile, said the opinion was in line with China’s views, while the White House said the US would put itself and its interests first.

One particularly positive response came from Ralph Regenvanu, minister of climate change adaptation, meteorology and geo-hazards, energy, environment and disaster management for the Republic of Vanuatu, who commended the opinion. In a statement, he said:

“The ICJ ruling marks an important milestone in the fight for climate justice. We now have a common foundation based on the rule of law, releasing us from the limitations of individual nations’ political interests that have dominated climate action. This moment will drive stronger action and accountability to protect our planet and peoples.

Vishal Prashad, director of Pacific Islands Students Fighting Climate Change, welcomed the ICJ’s statements on what he said was the need to “urgently phase out fossil fuels…because they are no longer tenable”. He continued:

“For small island states, communities in the Pacific, young people and future generations, this opinion is a lifeline and an opportunity to protect what we hold dear and love. I am convinced now that there is hope and that we can return to our communities saying the same. Today is historic for climate justice and we are one step closer to realising this.”

The reaction from developed countries was more muted, with France stating that the “landmark opinion will be studied very closely”. It reaffirmed its “unwavering commitment to the ICJ”.

A spokesperson for the European Commission, Anna-Kaisa Itkonen, told the media that the opinion “confirms the magnitude of the challenge we face and the importance of climate action”. She added that the commission would examine what the opinion “precisely implies” and noted that the EU’s emissions are behind those of China, the US and India.

A spokesperson for China’s foreign ministry said in a regular press conference that the ICJ opinion was “of positive significance to maintaining and advancing international climate cooperation”.

They added that, in their view, the court reinforced the “long-standing stance” of China, whereby developed countries should “take the lead” in tackling climate change:

“We noted that the ICJ’s advisory opinion pointed out that the UNFCCC system is the principal legal instruments regulating the international response to the global problem of climate change and confirmed that the principle of common but differentiated responsibility, the principle of sustainable development and the principle of equity are applicable as guiding principles for the interpretation and application of relevant international law.”

In response to the opinion, a spokesperson for the White House told Reuters:

“As always, President Trump and the entire administration is committed to putting America first and prioritising the interests of everyday Americans.”

Many within the wider international community also welcomed the advisory opinion. For example, Mary Robinson, a member of the Elders and the first woman president of Ireland and former UN high commissioner for human rights, called the opinion a “powerful new tool to protect people from the devastating impacts of the climate crisis – and to deliver justice for the harm their emissions have already caused”.

António Guterres, secretary-general of the UN said in a statement that the ICJ had issued a “historic” opinion. He added:

“They made clear that all States are obligated under international law to protect the global climate system. This is a victory for our planet, for climate justice and for the power of young people to make a difference. Young Pacific Islanders initiated this call for humanity to the world. And the world must respond.”

Charities such as Amnesty International, Earthjustice and Greenpeace hailed the “landmark moment for climate justice and accountability”.

Tasneem Essop, executive director of Climate Action Network International, said that “the era of impunity is over”, adding that the ruling “could not have come at a better time” ahead of the upcoming COP30 summit.

Within the media, a lot of coverage focused on the potential that nations might have to pay reparations for breaching their climate obligations.

In the Guardian, Harj Narulla, barrister and leading global expert on climate litigation at Doughty Street Chambers and the University of Oxford, discusses what the ICJ’s advisory opinion could mean for Australia and other major polluters in a “new era of climate reparations”.

In its news coverage, the Daily Telegraph says that the UN “has opened the door to Britain being sued over its historic contribution to climate change”. It adds that the opposition Conservative and Reform parties “both rejected the ruling”.