This is the first article in our four-part series “Boon or bane: What will data centers do to the grid?”

In January, Virginia lawmakers unveiled a raft of legislation aimed at putting some guardrails on a data center industry whose insatiable hunger for electricity threatens to overwhelm the grid.

As the home of the world’s densest data center hub, Virginia is on the vanguard of dealing with these challenges. But the state is far from alone in a country where data center investments may exceed $1 trillion by mid-2029, driven in large part by “hyperscalers” with aggressive AI goals, like Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft.

“If we fail to act, the unchecked growth of the data center industry will leave Virginia’s families, will leave their businesses, footing the bill for infrastructure costs, enduring environmental degradation, and facing escalating energy rates,” state Sen. Russet Perry, a Democrat representing Loudoun County, the heart of Virginia’s “Data Center Alley,” told reporters at the state capitol in Richmond last month. “The status quo is not sustainable.”

Perry’s position is backed by data. A December report commissioned by Virginia’s legislature found that a buildout of data centers to meet “unconstrained demand” would double the state’s electricity consumption by 2033 and nearly triple it by 2040.

To meet the report’s unconstrained scenario, Virginia would need to erect twice as many solar farms per year by 2040 as it did in 2024, build more wind farms than all the state’s current offshore wind plans combined, and install three times more battery storage than Dominion Energy, the state’s biggest utility, now intends to build.

Even then, Virginia would need to double current power imports from other states. And it would still need to build new fossil-gas power plants, which would undermine a state clean energy mandate. Meeting just half the unconstrained demand would require building seven new 1.5-gigawatt gas plants by 2040. That’s nearly twice the 5.9 gigawatts’ worth of gas plants Dominion now plans to build by 2039, a proposal that is already under attack by environmental and consumer groups.

But Perry and her colleagues face an uphill battle in their bid to more closely regulate data center growth. Data centers are big business in Virginia. Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, has called for the state to “continue to be the data center capital of the world,” citing the up to 74,000 jobs, $9.1 billion in GDP, and billions more in local revenue the industry brings. Most of the proposed data center bills, which include mandates to study how new data centers could impose additional costs on other utility customers and worsen grid reliability, have failed to move forward in the state legislature as of mid-February.

Still, policymakers can’t avoid their responsibility to “make sure that residential customers aren’t necessarily bearing the burden” of data center growth, Michael Webert, a Republican in Virginia’s House of Delegates who’s sponsoring one of the data center bills, said during last month’s press conference.

From the mid-Atlantic down to Texas, tech giants and data center developers are demanding more power as soon as possible. If utilities, regulators, and policymakers move too rashly in response, they could unleash a surge in fossil-gas power-plant construction that will drive up consumer energy costs — and set back progress on shifting to carbon-free energy.

But this outcome is not inevitable. With some foresight, the data center boom can actually help — rather than hurt — the nation’s already stressed-out grid. Data center developers can make choices right now that will lower grid costs and power-system emissions.

And it just so happens that these solutions could also afford developers an advantage, allowing them to pay less for interconnection and power, win social license for their AI products, and possibly plug their data centers into the grid faster than their competitors can.

When it comes to the grid, the nation faces a computational crossroads: Down one road lie greater costs, slower interconnection, and higher emissions. Down the other lies cheaper, cleaner, faster power that could benefit everyone.

After decades with virtually no increase in U.S. electricity demand, data centers are driving tens of gigawatts of power demand growth in some parts of the country, according to a December analysis from the consultancy Grid Strategies.

Providing that much power would require “billions of dollars of capital and billions of dollars of consumer costs,” said Abe Silverman, an attorney, energy consultant, and research scholar at Johns Hopkins University who has held senior policy positions at state and federal energy regulators and was an executive at the utility NRG Energy.

Utilities, regulators, and everyday customers have good reason to ask if the costs are worth it — because that’s far from clear right now, he said.

A fair amount of this growth is coming from data centers meant to serve well-established and solidly growing commercial demands, such as data storage, cloud computing, e-commerce, streaming video, and other internet services.

But the past two years have seen an explosion of power demand from sectors with far less certain futures.

A significant, if opaque, portion is coming from cryptocurrency mining operations, notoriously unstable and fickle businesses that can quickly pick up and move to new locations in search of cheaper power. The most startling increases, however, are for AI, a technology that may hold immense promise but that doesn’t yet have a proven sustainable business model, raising questions about the durability of the industry’s power needs.

Hundreds of billions of dollars in near-term AI investments are in the works from Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft as well as private equity and infrastructure investors. Some of their announcements strain the limits of belief. Late last month, the CEOs of OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank joined President Donald Trump to unveil plans to invest $500 billion in AI data centers over the next four years — half of what the private equity firm Blackstone estimates will be invested in U.S. AI in total by 2030.

Beyond financial viability, these plans face physical limits. At least under current rules, power plants and grid infrastructure simply can’t be built fast enough to provide what data center developers say they need.

Bold data center ambitions have already collided with reality in Virginia.

“It used to take three to four years to get power to build a new data center in Loudoun County,” in Virginia’s Data Center Alley, said Chris Gladwin, CEO of data analytics software company Ocient, which works on more efficient computing for data centers. Today it “takes six to seven years — and growing.”

Similar constraints are emerging in other data center hot spots.

The utility Arizona Public Service forecasts that data centers will account for half of new power demand through 2038. In Texas, data centers will make up roughly half the forecasted new customers that are set to cause summer peak demand to nearly double by 2030. Georgia Power, that state’s biggest utility, has since 2023 tripled its load forecast over the coming decade, with nearly all of that load growth set to come from the projected demands of large power customers including data centers.

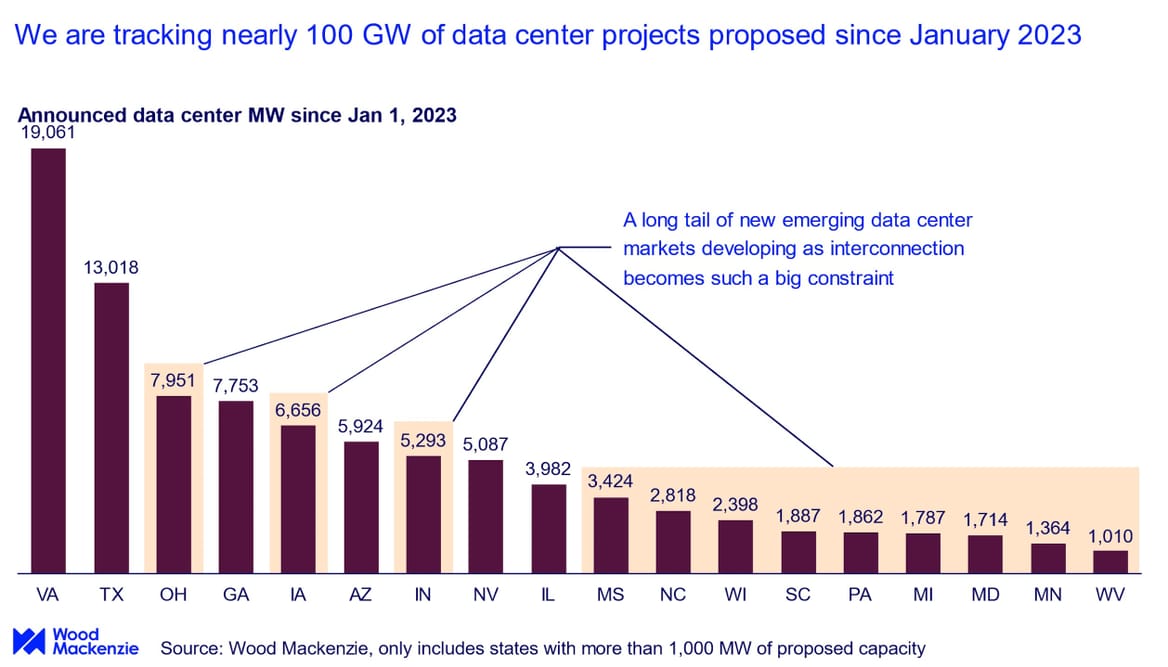

These saturated conditions are pushing developers into new markets, as the below chart from the energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie shows.

“There’s more demand at once seeking to connect to the system than can be supplied,” Chris Seiple, vice chairman of Wood Mackenzie’s power and renewables group, said in a December interview.

Of that demand growth, only a fraction can be met by building new solar and wind farms, Seiple added. And “unfortunately, those additions aren’t necessarily happening where a lot of the demand growth is happening, and they don’t happen in the right hours,” he said.

Seiple is referring to data centers’ need for reliable round-the-clock power, and utilities’ responsibility to provide it, including at moments of peak demand, usually during hot summers and cold winters. A lot of the money utilities spend goes toward building the power plants and grid infrastructure needed to meet those demand peaks.

Where renewables fall short, other resources like carbon-free hydropower, nuclear, geothermal, or clean-powered batteries could technically be built to serve at least a large portion of data center demand. But that’s generally not what’s playing out on the ground.

Instead, the data center boom is shaping up to be a huge boon for fossil-gas power plants. Investment bank Goldman Sachs predicts that powering AI will require $50 billion in new power-generation investment by 2030: 40% of it from renewables and 60% from fossil gas.

Even tech firms with clean energy goals, like Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft, are having trouble squaring their soaring power needs with their professed climate commitments.

Over the past decade, those four companies have secured roughly 40 GW of U.S. clean power capacity, according to research firm BNEF. But in the past four years, their growing use of grid power, which is often generated using plenty of fossil gas, has pushed emissions in the wrong direction. Google has seen a 48% increase since 2019, and Microsoft a 29% jump since 2020.

The inability to match growing demand with more clean power isn’t entirely these hyperscalers’ fault. Yearslong wait times have prevented hundreds of gigawatts of solar and wind farms and batteries from connecting to congested U.S. power grids.

Tech firms are also pursuing “clean firm” sources of power. Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft have pledged to develop (or restart) nuclear power plants, and Google has worked with advanced-geothermal-power startup Fervo Energy. But these options can’t be brought online or scaled up quickly enough to meet short-term power needs.

“The data center buildout, especially now with AI, is creating somewhat of a chaotic situation,” said James West, head of sustainable technologies and clean-energy research at investment banking advisory firm Evercore ISI. Hyperscalers are “foregoing some of their sustainability targets a bit, at least near-term.”

And many data center customers and developers are indifferent to clean energy; they simply seek whatever resource can get their facility online first, whether to churn out cryptocurrency or win an advantage in the AI race.

Utilities that have sought for years to win regulatory approval for new gas plants have seized on data center load forecasts as a new rationale.

A recent analysis from Frontier Group, the research arm of the nonprofit Public Interest Network, tallied at least 10.8 GW of new gas-fired power plants being planned by utilities, and at least 9.1 GW of fossil-fuel power plants whose closures have been or are at risk of being delayed, to meet projected demand.

In Nebraska, the Omaha Public Power District has delayed plans to close a 1950s-era coal plant after Google and Meta opened data centers in its territory. Last year, Ohio-based utility FirstEnergy abandoned a pledge to end coal use by 2030 after grid operator PJM chose it to build a transmission line that would carry power from two of its West Virginia coal plants to supply northern Virginia.

“This surge in data centers, and the projected increases over the next 10 years in the electricity demand for them, is really already contributing to a slowdown in the transition to clean energy,” said Quentin Good, policy analyst with Frontier Group.

In some cases, tech companies oppose these fossil-fuel expansion plans.

Georgia Power last month asked regulators to allow it to delay retirement of three coal-fired plants and build new gas-fired power plants to meet a forecasted 8 GW of new demand through 2030. A trade group representing tech giants, which is also negotiating with the utility to allow data centers to secure more of their own clean power, was among those that criticized the move for failing to consider cleaner options.

But in other instances, data center developers are direct participants.

In Louisiana, for example, Meta has paired a $10 billion AI data center with utility Entergy’s plan to spend $3.2 billion on 1.5 GW’s worth of new fossil-gas power plants.

State officials have praised the project’s economic benefits, and Meta has pledged to secure clean power to match its 2 GW of power consumption and to work with Entergy to develop 1.5 GW of solar power. But environmental and consumer advocates fear the 15-year power agreement between Meta and Entergy has too many loopholes and could leave customers bearing future costs, both economic and environmental.

“In 15 years, Meta could just walk away, and there would be three new gas plants that everyone else in the state would have to pay for,” said Logan Atkinson Burke, executive director of the nonprofit Alliance for Affordable Energy. The group is demanding more state scrutiny of the deal and has joined other watchdog groups in challenging Entergy’s plan to avoid a state-mandated competitive bidding process to build the gas plants.

In other cases, AI data center developers appear to be making little effort to coordinate with utilities. In Memphis, Tennessee, a data center being built by xAI, the AI company launched by Elon Musk, was kept secret from city council members and community groups until its June 2024 unveiling.

In the absence of adequate grid service from Memphis’ municipal utility, the site has been burning gas in mobile generators exempt from local air-quality regulations, despite concerns from residents of lower-income communities already burdened by industrial air pollution.

In December, xAI announced a tenfold increase in the site’s computing capacity — a move that the nonprofit Southern Alliance for Clean Energy estimates will increase its power demand from 150 MW to 1 GW, or roughly a third of the entire city’s peak demand.

The nonprofit had hoped that “Musk would use his engineering expertise to bring Tesla megapacks [batteries] with solar and storage capability to make this facility a model of clean, renewable energy,” its executive director, Stephen Smith, wrote in a blog post. But now, the project seems more like “a classic bait and switch.”

If gas plants are built as planned to power data centers, dreams of decarbonizing the grid in the near future are essentially out the window.

But data centers don’t need to be powered by fossil fuels; it’s not a foregone conclusion.

As Frontier Group’s Good noted during last month’s Public Interest Network webinar, “The outcome depends on policy, and the increase in demand is by no means inevitable.”

It’s up to regulators to sort this out, said Silverman of Johns Hopkins University. “There are all these tradeoffs with data centers. If we’re asking society to make tradeoffs, I think society has a right to demand something from data centers.”

That’s what the Virginia lawmakers proposing new data center bills said they were trying to do. Two of the bills would order state regulators to study whether other customers are bearing the costs of data center demand — a risk highlighted by the legislature’s December report, which found unconstrained growth could increase average monthly utility bills by 25% by 2040. Those bills are likely to be taken up in conference committee next month.

Other bills would give local governments power to review noise, water, and land-use impacts of data centers seeking to be sited in the state, require that data centers improve energy efficiency, and mandate quarterly reports of water and energy consumption.

Another sought to require that proposed new data centers undergo review by state utility regulators to ensure they won’t pose grid reliability problems. Democratic Delegate Josh Thomas, the bill’s sponsor, said that’s needed to manage the risks of unexamined load growth. Without that kind of check, “we could have rolling blackouts. We could have natural gas plants coming online every 18 months,” he said.

But that bill was rejected in a committee hearing last month, after opponents, including representatives of rural counties eager for economic development, warned it could alienate an industry that’s bringing billions of dollars per year to the state’s economy.

Data center developers have the ability to minimize or even help drive down power system costs and carbon emissions. They can work with utilities and regulators to bring more clean energy and batteries onto the grid or at data centers themselves. They can manage their demand to reduce grid strains and lower the costs of the infrastructure needed to serve them. And in so doing, they could secure scarce grid capacity in places where utilities are otherwise struggling to serve them.

The question is, will they? Silverman emphasized that utilities and regulators must treat grid reliability as their No. 1 priority. “But when we get down to the next level, are we going to prioritize affordability, which is very important for low-income customers? Are we going to prioritize meeting clean energy goals? Or are we going to prioritize maximizing data center expansion?” he asked.

Given the pressure to support an industry that’s seen as essential to U.S. economic growth and international competitiveness, Silverman worries that those priorities aren’t being properly balanced today. “We’re moving forward making investments assuming we know the answer — and it’s not like if we’re wrong, we’re getting that money back.”

In part 2 of this series, Canary Media reports on a key problem with data center plans: It’s near impossible to know how much they’ll impact the grid.