The megabill passed by Republicans in Congress and signed into law by President Donald Trump last week creates many challenges for clean energy — enough to choke off lots of new solar and wind power projects, and cast uncertainty over everything from battery storage deployments to EV factories.

The only saving grace is that it could have been much worse.

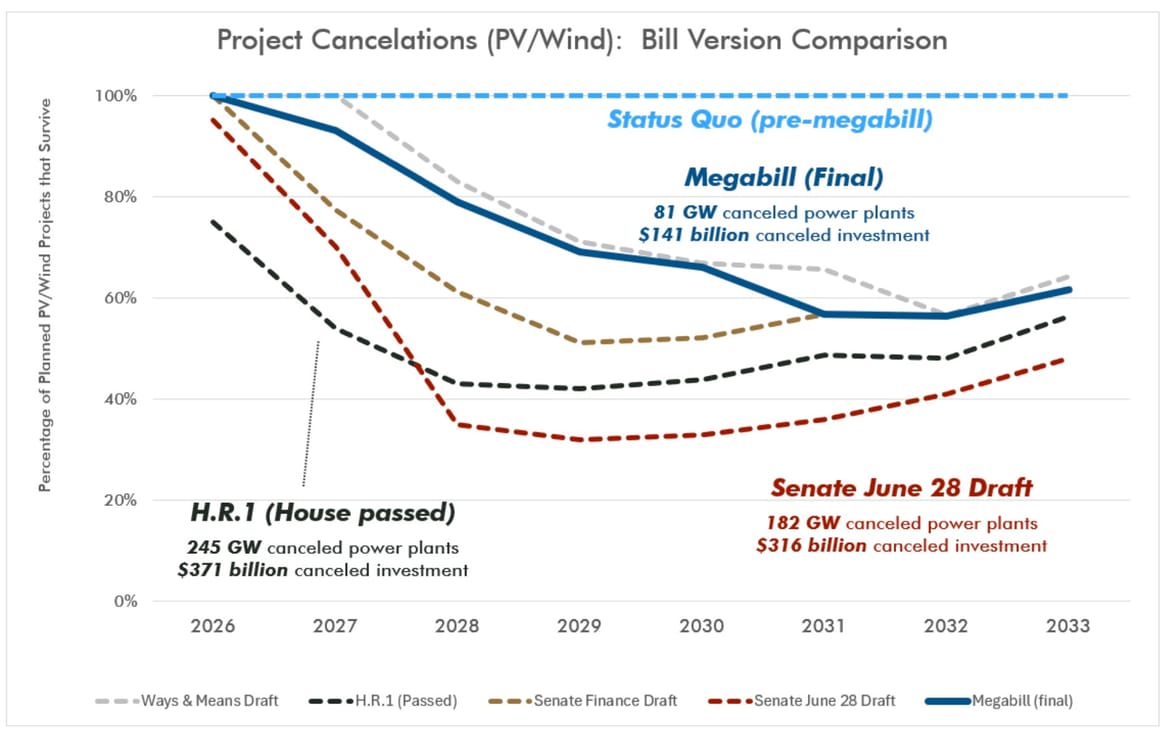

The new law could reduce investment in solar and wind projects by about $141 billion and kill 81 gigawatts of potential new generation capacity through 2033 compared to what would have happened if it didn’t pass, according to estimates from solar and battery project investor Segue Sustainable Infrastructure.

But previous versions of the bill from House Republicans, and a draft unveiled by Senate Republicans on June 28, would have spelled the demise of more than twice as much clean power and domestic investment, according to Segue’s previous analyses.

What changed? A handful of Senate Republicans, pressed by clean energy advocates, amended the bill in the industry’s favor, averting “a complete catastrophe,” according to David Riester, founder and managing partner of Segue, which is involved in about 120 solar and battery projects across the country.

Nevertheless, the law still rapidly phases out tax credits for solar and wind.

Under the Inflation Reduction Act, projects that started construction before 2033 were assured tax credits that they could use or sell to reduce the cost of building, and thus, the price of the power they offer to long-term offtakers, like utilities or corporations. Although the new law largely preserves that timeline for geothermal, nuclear, hydropower, and battery storage development, it dramatically tightens the deadlines for wind and solar projects, requiring them to either be operating by the end of 2027 or start construction by next summer to access incentives.

Developers and financiers like Segue now have 12 months to decide whether they believe a given wind or solar installation can hit the milestones required to access crucial tax credits.

If they don’t think it can, they’ll pull out of the project. That could mean a lot of abandoned plans for Segue, whose portfolio is mostly made up of earlier-stage developments.

“We often pose the question to each other: ‘If we lean into this, are we investing, or are we gambling?’’’ Riester said. “There are some project profiles for which the answer will almost certainly be ‘gambling’ a year from now, and we will kill those.”

Segue isn’t alone. Financiers and developers across the country are grappling with this as they consider whether to move forward with much of the hundreds of gigawatts of solar, battery, and wind projects being planned around the country.

“When you rip the rug out suddenly, it creates a moment where the owners of all these projects, in their various stages of development, have to face the fact that they don’t know exactly what their revenue line is going to look like,” Riester said.

Developers ultimately have little control over when a project can connect to the grid and start delivering power. That’s why the most vital change in the final version of the bill is one pushed by Sens. Joni Ernst (R-Iowa), Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), and Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), which gives wind and solar projects until July 4, 2026, to start construction to secure tax credit eligibility.

Projects that meet this deadline will be eligible as long as they’re completed and placed in service within four years of start of construction. Previous versions of the bill would have given those projects only 60 days to commence construction, and then required them to be placed into service by 2028 to win credits.

But project developers called the “placed in service” deadline tantamount to an immediate tax-credit cutoff, given the impossibility of being able to assure investors that they’d be able to get online in time. Already, grid bottlenecks force projects to wait an average of five years to secure interconnection.

The “commence construction” status is the traditional hinge point for tax credit eligibility. It’s far more within a developer’s control than placing a project into service, and can be verified using established methods like the “5% safe-harbor test,” which involves incurring 5% or more of the total cost of the facility in the year construction begins.

With 12 months to reach this construction milestone, project developers have “a bit more time to see how projects’ existing development risks evolve before the ‘Do I safe harbor this project?’ question requires an answer and action,” Riester said.

There is a cloud hanging over relying on safe harbor provisions, however, noted Andy Moon, CEO and cofounder of Reunion Infrastructure, a company working in the multibillion-dollar market for clean-energy tax credit transfers. President Trump issued an executive order on Monday directing the Treasury Department to issue guidance restricting the use of “broad safe harbors unless a substantial portion of a subject facility has been built.”

That’s a “significant departure” from what project developers were planning for, Moon said. “Developers are scrambling to figure out how the Treasury might modify safe harbor rules.”

Not all of the wind and solar farms that could get started in the next 12 months will be able to, said Jim Spencer, president and CEO of Exus Renewables North America, a company that owns and builds clean energy.

The new mid-2026 deadline will launch a rush to secure all the equipment that projects require. Some developers will inevitably be crowded out, unable to buy what they need in time.

“We’re a well-capitalized developer with the ability to buy equipment in advance,” Spencer said, but not all firms are in the same position. “A lot of the less well-capitalized developers may have good projects. But if they can’t grandfather those projects, either by starting construction or by procuring equipment, there’s not much of a value proposition there.”

That looming deadline also presages a big drop in new solar and wind projects later this decade, once the last ones eligible for tax credits are built.

“You’ll have a rush of safe-harboring” before the 12-month period expires, Moon said. “But greenfield development is going to freeze after that until the market adjusts.”

That’s because energy buyers won’t immediately want to accept the higher prices set by developers who lack the financial boost of tax credits. “There’s going to be a price-discovery phase, when project developers all of a sudden are missing capital for 30% to 40% to 50% of their project costs,” he said. “Electricity prices are going to have to rise significantly to make up the shortfall.”

Wholesale electricity prices could increase 25% by 2030 and 74% by 2035 due to the loss of low-cost renewable energy and a rise in the cost of fossil gas to fuel the power plants that will need to make up the difference, according to modeling of the law from think tank Energy Innovation.

The process of price discovery will lead to what Riester described as a “price correction” — energy buyers coming to terms with how much more expensive electricity will become and making deals accordingly. But that will take some time.

In the meantime, there will be a gap in the deployment of clean energy — by far the biggest source of new power on the U.S. grid. That gap will have consequences as power demand is climbing nationwide.

Slower power-plant growth will significantly disrupt the electricity needs of factories, data centers, big-box stores, and “everything that we want to bring back onshore” that are “teed to these power projects,” Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), one of three Senate Republicans who voted against the bill, said in a speech on the chamber’s floor in late June. The disruptions will cause “a blip in power service, because there isn’t going to be a gas-fired generator anytime soon.”

Developers face wait times of five to seven years for new gas turbines. Nuclear and geothermal power plants take even longer to build.

Eventually, the market will find a new equilibrium. If solar, wind, and batteries are the only power sources that can be built quickly in the near term, utilities and corporate customers will figure out a price they’re willing to pay.

“But on the way to that steady state, there will be a lot of rockiness in the market,” Riester said. During that time, Segue and many other energy-market observers predict a significant shortfall in new power supply to meet demand.

“There will still be tons of projects in that 2028 to 2031 window that get killed because visibility into economic viability fails to arrive before development expenses become uncomfortably high,” Riester said. “That’s where the capacity shortage is likely to peak” — when Trump’s presidency will be over.