San Francisco already requires most new buildings to eschew gas and run solely on electricity. Now, the metropolis is moving to ensure that substantial renovations in existing buildings are also all-electric.

Last week, the city and county’s Board of Supervisors completed the first of two votes to pass the All-Electric Major Renovations Ordinance, a climate-forward building standard that will apply to commercial and residential structures. The initial 11–0 vote was a resounding sign of approval; the final hearing is likely to occur Sept. 2, according to the San Francisco Environment Department, the agency that developed the rules.

“We can’t build the San Francisco of the future with fuel from the past,” Board of Supervisors President Rafael Mandelman said in a statement. “This legislation picks up where we left off with the All-Electric New Construction ordinance and affords us the opportunity to eliminate the use of fossil fuels in our existing buildings, improve indoor and outdoor air quality, and make San Francisco a safer, healthier, and more resilient place to live and work.”

The proposed ordinance was years in the making, but the city is now fast-tracking its approval before a new statewide pause on updates to building codes kicks in. Under the law, signed in June, San Francisco and other jurisdictions in the Golden State have only until Oct. 1 to adopt stronger building codes unless they claim an exception.

San Francisco can’t meet its climate goals unless it moves buildings away from fossil fuels. The city has vowed to slash carbon pollution by 61% from 1990 levels by 2030 and to achieve net-zero emissions by 2040 — five years faster than California as a whole. Buildings in San Francisco account for 44% of the city’s planet-warming pollution, the largest emitter after transportation, at 45%.

If enacted, the new ordinance will affect projects that are similar in scope to new construction, including additions as well as renovations that rip out mechanical systems. It won’t bear on single equipment replacements, however, like replacing a gas furnace.

The ordinance essentially “closes a loophole” in the new construction requirement, Cyndy Comerford, climate program manager at the SF Environment Department, told Canary Media. For example, on the same downtown parcel of a five-story brick building, a whopping 46-story glass edifice was recently added, she said. “That addition was allowed to have gas in it when it was a totally separate building.” The new ordinance would put a stop to similar cases in the future.

Lawmakers are leaving room for exceptions to the all-electric standard, including restaurants that use gas for cooking, buildings composed of 100% affordable housing units (with gradual compliance after July 2027), and projects that can’t get enough power from the utility in time. Building owners would seek exemptions from the SF Environment Department.

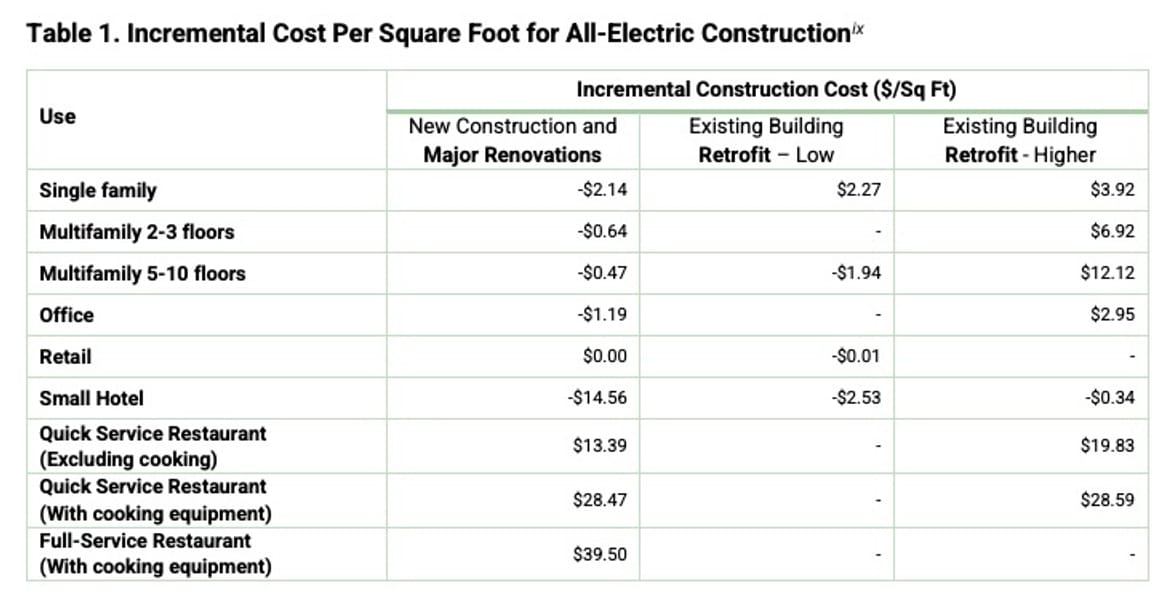

In many cases, the cost of all-electric construction is actually lower than that of mixed-fuel buildings, according to the department. Summarizing several analyses, it estimates that newly built or majorly renovated all-electric single-family homes are cheaper than conventional construction by more than $2 per square foot, on average.

Contrast that to the higher estimated costs to switch to all-electric appliances after construction. The department estimates such retrofits would cost San Francisco homeowners an added $2 to $4 per square foot.

And all-electric retrofits are coming.

In 2023, San Francisco Bay Area air regulators passed landmark rules to phase out the sale of gas-burning water heaters by 2027 and furnaces by 2029 for single-family homes. When old combustion appliances conk out after those dates, homeowners will need to foot the bill to replace them with zero-emissions units. The same will hold for multifamily building owners by 2031.

“Developers aren’t always incentivized to think [about] who’s going to be living in this property 10 or 15 years from now,” said Tyrone Jue, director of the SF Environment Department. “And that’s where government has to step in to say … ‘Yes, we want you to build housing, but we want you to do it smartly so that we don’t end up having to carry the financial burden down the road.’”

Fossil gas also carries heavy social costs. In addition to contributing to an increasing drumbeat of climate disasters, burning fossil fuels in home appliances releases a slew of pollutants, from carbon monoxide to nitrogen oxides, that concentrate indoors and spill outdoors. These by-products can lead to respiratory disorders, cardiovascular disease, and premature death. One in eight childhood asthma cases are linked to gas stoves. All-electric equipment doesn’t emit these compounds.

“As a city, we’re responsible for the well-being of our citizens,” Comerford said.

Gas lines are also a particular liability in the earthquake-prone region. Liquefaction of the earth can sever underground pipelines, which are more prone to damage than the city’s electrical system, Jue said. In a 2020 report, utility Pacific Gas & Electric estimated that after a 7.9 earthquake, it would take up to six months to restore gas services citywide; electricity could be brought back on line in two weeks.

The all-electric renovations ordinance comes as the federal government is rolling back environmental regulations and pushing for more fossil fuel use, not less. “This is a moment for cities like San Francisco to step up,” Jue said. “And this is San Francisco drawing a clear line, not waiting for permission from Washington to protect our people, our health, and the planet.”