Everyone agrees that California’s major utilities are charging too much for electricity. But as in previous years, state lawmakers, regulators, and consumer advocates are at odds over what to do about it.

With the state’s three biggest utilities reporting record profits even as customers’ rates have skyrocketed, critics say the time is right to pass laws that will force regulators to more tightly control key utility costs — or even outright curb utility spending and profits.

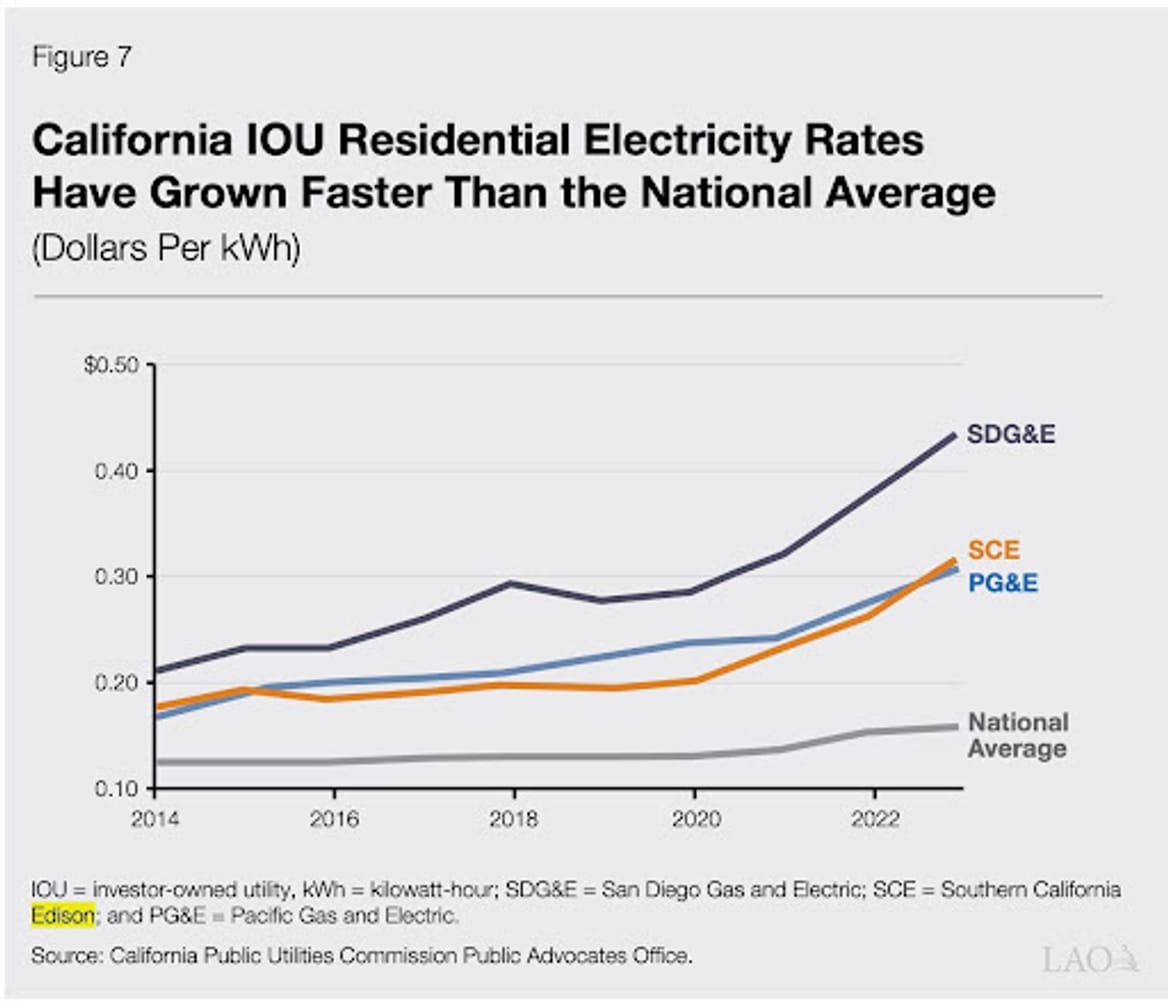

Customers of Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric now pay roughly twice the national average for their power, with average residential rates rising 47% from 2019 to 2023, according to a January report from the state Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Rates are set to climb even further in the coming years as utilities look to expand their power grids to meet growing demand from data centers, electric vehicle charging depots, and millions of households buying EVs and heat pumps. Utilities also need to build high-voltage transmission lines to connect far-off clean energy resources to population centers. And they need to harden and protect thousands of miles of low-voltage power lines to prevent deadly wildfires in a landscape that’s growing more susceptible to conflagration because of climate change.

Utilities are allowed to earn a profit on these infrastructure investments and to pass the costs onto customers — but only within reason. It’s the job of regulators to ensure that profits aren’t disproportionate to what utilities charge ratepayers.

Consumer advocates are now demanding that the California Public Utilities Commission be more aggressive in challenging PG&E, SCE, and SDG&E’s spending plans, which have allowed them to earn more profits than ever over the past year. In October, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) ordered the CPUC to issue a report on how to curb rate increases.

“There’s agreement that record-breaking shareholder earnings make no sense along with skyrocketing costs,” said Mark Toney, executive director of The Utility Reform Network (TURN), a ratepayer advocacy group, and that “utilities need to be held more accountable for their spending.”

TURN is supporting a list of bills being introduced in this year’s legislative session that take aim at utility costs. Some would increase state regulator oversight on utility grid spending. Others seek to forbid utilities from spending ratepayer funds on lobbying and advertising and strengthen CPUC oversight of potential “double recovery,” or utilities collecting funds for projects already financed via other means.

Beyond TURN’s list of favored bills, there are more aggressive legislative proposals that would limit utility rate increases to no higher than the general rate of inflation and force utility shareholders to pay more into a state fund created to shelter utilities from bankruptcy as a result of having to pay for catastrophic wildfires caused by their equipment. PG&E was forced into bankruptcy in 2019 under these conditions after a failure of one of its power lines sparked the state’s deadliest-ever wildfire in 2018.

Legislation that would order the CPUC to increase oversight of utility spending or limit the costs utilities can pass on to customers faces an uphill battle. Last year, a number of reform proposals faltered in the face of heavy lobbying from utility workers unions and pushback from utilities, which spend generously on state political campaigns.

But with customers of California’s three big utilities now paying the highest rates in the nation outside Hawaii and one in five California households struggling to pay their monthly bills, the public pressure to do something may outweigh utility lobbying muscle, advocates say.

Last month, the California state Senate Energy, Utilities and Communications Committee held a legislative hearing where the CPUC briefed lawmakers on its new report on how to contain rate increases.

That report shied away from suggesting major clawbacks in utility spending or limiting profits. Instead, it focused on shifting some costs now passed through to ratepayers — including payments to customers who have rooftop solar, wildfire mitigation and recovery investments, and programs that boost energy efficiency and help low-income customers pay their bills — to “other sources of funding.” That could include state taxpayers, California’s cap-and-trade program, or customers of publicly owned utilities.

All of these proposals would require legislative action, and some lawmakers pushed back on the idea that utilities should be able to shift costs that are their responsibility under law. But CPUC President Alice Reynolds said the alternative — forcing utility shareholders rather than ratepayers to bear more costs — could violate legal precedents that allow utilities a “reasonable rate of return to attract investment in the system,” as she put it.

State Sen. Josh Becker (D), chair of the committee, said during the hearing that legislative leaders and Gov. Newsom’s office plan to put together a bill focused on energy affordability in the coming months.

Toney said he’s hopeful this affordability package “has some of the proposals that went down at the last minute last year, and that there’s going to be a lot more support for them” this year. But he was also critical of the CPUC’s report. “I’ll tell you what was missing” from it, he said — “any conversations about utility profits.”

PG&E, the state’s biggest utility, has reported record-breaking profits over the past two years. The average customer bill increased more than 35% between 2021 and 2023, and CPUC approved six PG&E rate hikes in 2024. The utility’s rates will increase again this year to cover the cost of keeping the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant open.

SCE, the state’s largest electric-only utility, reported record-setting profits in 2024, after winning CPUC approval for rate hikes last year. Another rate hike was approved in January.

SDG&E reported profits near its all-time high last year after record-high profits in 2023 and 2022. The utility’s rates have increased to become among the highest in the nation, as shown in this chart from the state Legislative Analyst’s Office.

The CPUC’s report stated that “the biggest drivers of rate increases” are “the growth in spending to address wildfire mitigation” as well as “the cost shift that results from legacy Net Energy Metering programs,” which compensate customers with rooftop solar systems for electricity they send back to the grid. The CPUC delegated to secondary status the costs of “energy transition related investments in transmission and distribution infrastructure.”

But rooftop solar incentives don’t deserve most of the blame for rising rates, said Loretta Lynch, an attorney and energy policy expert who served as CPUC president from 2000 to 2002. She is also a longtime critic of the current CPUC commissioners appointed by Gov. Newsom.

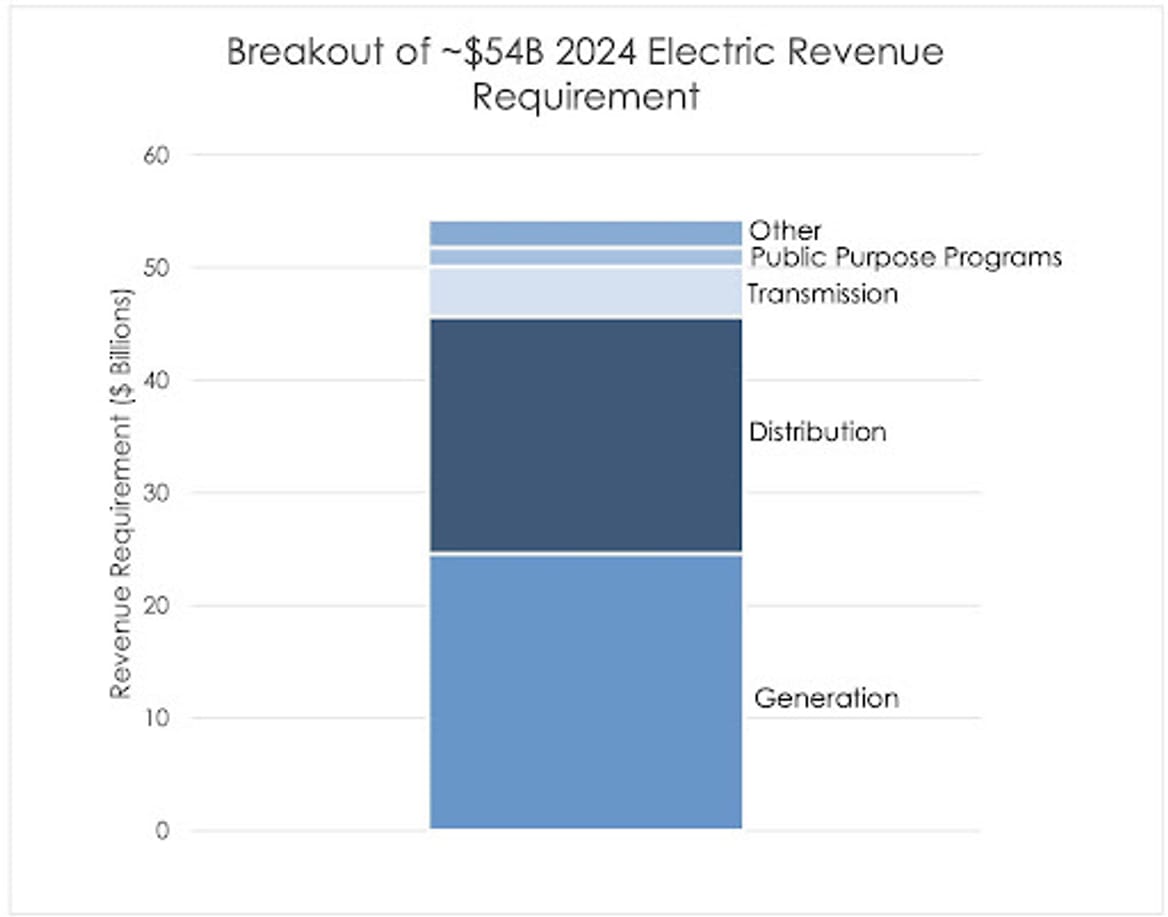

Instead, she said during a February webinar presenting new data on the connection between utility spending and rising rates, “the primary drivers of a vast majority of the costs over the last five to 10 years have been extraordinary procurement” of clean energy at the early stages of the state’s energy transition, when solar power was far more expensive than today, and, more notably, “the tripling of the costs of transmission and distribution” grid investments over the past decade.

Other energy analysts, including some who strongly disagree with Lynch’s views on rooftop solar, share this perspective on the grid’s role in driving up utility costs.

Severin Borenstein, head of the Energy Institute at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, is a major backer of the proposition that rooftop solar is causing bills to rise for other customers. He reiterated that position in a February presentation to the Little Hoover Commission, an independent state oversight agency, noting the significant costs of “public purpose programs,” such as the billions of dollars that utility customers at large pay to support rooftop solar incentives and low-income ratepayer assistance.

But Borenstein also said a majority of the rising utility costs over the past decade are tied to investments in low-voltage distribution grids and wildfire hardening and prevention.

“Those last two sort of meld together because we’re spending a whole lot of money on upgrading our distribution network, reinforcing our distribution network, in some cases, under-grounding it, in order to reduce wildfires,” he said.

The below chart from the CPUC’s February report highlights the majority of costs that come from paying for electricity generation and maintaining the utilities’ sprawling low-voltage distribution grids.

Borenstein agrees with the CPUC that rooftop solar incentives make up a significant portion of rising utility rates — a view that’s disputed by solar and environmental advocates. But even when the costs of net metering are calculated in the way that the CPUC proposes, they still make up a relatively small portion of typical residential utility customer bills compared to the “other” category that includes generation and grid costs, as the below chart from the Legislative Analyst’s Office report shows.

The Natural Resources Defense Council, one of the few environmental organizations that strongly favors reducing rooftop solar compensation, issued a report this week proposing a host of ways to reduce PG&E’s rates, including shifting those costs away from ratepayers. But NRDC also found that the “largest contributor to PG&E’s skyrocketing rates is the cost of vegetation management and hardening the grid to prevent wildfires,” making up more than half of the utility’s rate increases above the rate of inflation since 2018.

Going after those costs is tricky, however. When it comes to generation, utilities can’t back out of contracts for expensive power, even if they were signed more than a decade ago. Nor can they avoid buying power on the state’s energy markets during times when those prices spike.

Tackling grid costs puts regulators and lawmakers in a bind as well. Nobody wants utilities to skimp on critical investments like replacing aging equipment or protecting power lines from being knocked down by trees or high winds. Efforts to police utility grid investments risk forcing regulators and utilities to spend lots of time and effort delving into the minutiae of those plans without any clear promise of savings to show at the end of it.

Even so, Toney highlighted several bills being proposed this year, and others he hopes will be revived from last year’s session, that could drive down some of these costs.

On wildfire-related expenditures, he’d like to see a new bill that revives the policies proposed by SB 1003, a bill that failed to pass last year. The bill would have instructed the CPUC to limit utility wildfire spending outside of closely examined plans and put utility wildfire planning more squarely under the commission’s control.

Another option to address utility spending is AB 745, a bill that would increase state oversight of utility transmission grid upgrades. Energy analysts argue that a regulatory gap between federal and state authority over certain types of smaller grid projects has led to utility overspending on those projects. AB 745 cites a CPUC report that found $4.4 billion in transmission investments by California’s big utilities between 2020 and 2022, or nearly two-thirds of total grid spending, fell into this category.

California could also find other ways to pay for grid investments, Toney said. Those options can include securitization — having a utility issue bonds backed by the steady stream of payments its customers make on their bills — or the state issuing bonds to pay for certain utility costs. Both replace a portion of costs that are passed on to ratepayers, which “saves money because there’s no shareholder profit to be made,” he said.

SB 330, a bill proposed by state Sen. Steve Padilla (D), would authorize the state to “pilot projects to develop, finance, and operate electrical transmission infrastructure” via “low-cost public debt and alternative institutional models.” California will need to spend an estimated $45.8 billion to $63.2 billion on transmission by 2045, and an October report from the nonprofit Clean Air Task Force found that such public financing options could annually shave billions of dollars from rate increases in future years.

Some consumer advocates say lawmakers and regulators need to go after rising rates directly by limiting the return on investment that utilities are permitted to pass on to customers. Utility critics say that’s the most direct way to halt rate increases.

It’s also the most likely to trigger major pushback from utilities.

“We need to reduce the utilities’ profits to the national average or perhaps tie those profits to increases in safety,” Lynch proposed during February’s webinar. “As long as our policymakers focus on the wrong problem, we won’t find the right solution to reducing customers’ punishing and unwarranted bills.”

These efforts are hampered by the complexity and volume of data that goes into calculating such returns on investment as well as the fact that utilities control all the data. Indeed, utility critics have noted that recent rate-increase requests from PG&E have been approved by the CPUC in a perfunctory manner, with little to no attempt to order the utility to prove its cost increases were warranted.

Lynch blamed CPUC commissioners. ”It’s a fundamental failure of regulation, but it’s also a fundamental failure of political will to require the regulators to do their job as written in the law,” she said.

Utility finance expert Mark Ellis agreed that the CPUC needs to cut utilities’ profits. As an independent consultant and senior fellow at the American Economic Liberties Project, Ellis published a January paper accusing utilities of using financial legerdemain to justify excessive returns on their investments — and regulators of violating their duty to hold utilities to account.

The regulatory compact between states and investor-owned utilities boils down to this, he told Canary Media: “We’re going to give you a monopoly, but we won’t let you charge monopoly rents. Anything above your cost of capital is a monopoly rent.”

In an opinion piece in the San Francisco Chronicle, Ellis argued that California’s investor-owned utilities have been earning far above the cost of capital for decades — an assertion he backs up from experience working as former chief of corporate strategy and chief economist at Sempra, the holding company of Southern California Gas Co. and SDG&E.

The Energy Institute’s Borenstein agreed during his February presentation that utilities have “some important perverse incentives for capital investment” and that “cost of equity is the big point of contention because it’s hard to know what you need to pay stock shareholders to get them to invest.”

At the same time, “I don’t blame the CPUC for this,” he said. “I think the CPUC is massively understaffed and undercompensated, and they are just overwhelmed with the many things that they are required to do with limited staff. And when they get into these rate-of-return hearings, the utilities are able to bring world experts in finance.”

Ultimately, he said, “the CPUC is really outgunned and outmanned.”

Some lawmakers are going after utility profits more directly. SB 332, a bill sponsored by state Sen. Aisha Wahab (D), would cap investor-owned utility rate increases for residential customers to no more than the Consumer Price Index, a federal measure of cost-of-living inflation. It would also make shareholders rather than ratepayers provide more of the funding for the state’s utility wildfire fund — a sensitive issue amid rising investor uncertainty regarding SCE’s potential liability for January’s devastating Eaton Fire. SB 332 would also tie utility executive compensation to safety metrics.

“This bill flips the script and puts utility profits on the table,” said Roger Lin, a senior attorney at the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity, which supports the legislation. While he conceded the proposal will face serious pushback from utilities, “we have to start looking at the systemic causes of the affordability crisis we have today in California.”