2025 is a pivotal moment for climate action. Countries are submitting new climate commitments, otherwise known as "nationally determined contributions" or "NDCs," that will shape the trajectory of global climate progress through 2035.

These new commitments will show how boldly countries plan to cut their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, transform their economies, and strengthen resilience to growing threats like extreme weather, wildfires and floods. Collectively, they will determine how far the world goes toward limiting global temperature rise and avoiding the worst climate impacts.

A few countries, such as the U.S., U.K. and Brazil, have already put forward new climate plans — and their ambition is a mixed bag. But it's still early: Many more countries, including major emitters like the EU and China, have yet to reveal their NDCs and are expected to do so in the coming months.

We analyzed the initial submissions for a snapshot of how countries' climate plans are shaping up so far and what they reveal about the road ahead.

A decade ago, the world was headed toward 3.7-4.8 degrees C (6.7-8.6 degrees F) of warming by 2100, threatening catastrophic weather, devastating biodiversity loss and widespread economic disruptions. In response, the Paris Agreement set a global goal: limit temperature rise to well below 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) and strive to limit it to 1.5 degrees C (2.7 degrees F), thresholds scientists say can significantly lessen climate hazards. Though some impacts are inevitable — with extreme heat, storms, fires and floods already worsening — lower levels of warming dramatically reduce their severity. Every fraction of a degree matters.

To keep the Paris Agreement's temperature goals within reach, countries agreed to submit new NDCs every five years. These national plans detail how (and how much) each country will cut emissions, how they'll adapt to climate impacts like droughts and rising seas, and what support they'll need to deliver on those efforts.

Countries have gone through two rounds of NDCs so far, in 2015 and 2020-2021, with their commitments extending through 2030.

While the latest NDCs cut emissions more deeply than those from 2015, they still fall short of the ambition needed to hold warming to 1.5 or 2 degrees C. If fully implemented (including measures that require international support), they could bring down projected warming to 2.6-2.8 degrees C (4.7-5 degrees F). And without stronger policies to meet countries' targets, the world could be heading for a far more dangerous 3.1 degrees C (5.6 degrees F) of warming by 2100.

Now the third round is underway, with countries expected to set climate targets through 2035.

These new NDCs are expected to reflect the outcomes of the 2023 Global Stocktake, which was the first comprehensive assessment of global climate progress under the Paris Agreement. In addition to bigger emissions cuts in line with holding warming to 1.5 degrees C, the Stocktake called on countries to act swiftly in areas that matter most for addressing the climate crisis — especially fossil fuels, renewables, transport and forests — and to do more to build resilience to climate impacts.

2025 NDCs are also an opportunity to align near-term climate action with longer-term goals. Over 100 countries have already pledged to reach net-zero emissions, most by around mid-century. Their new NDCs should chart a course toward achieving this.

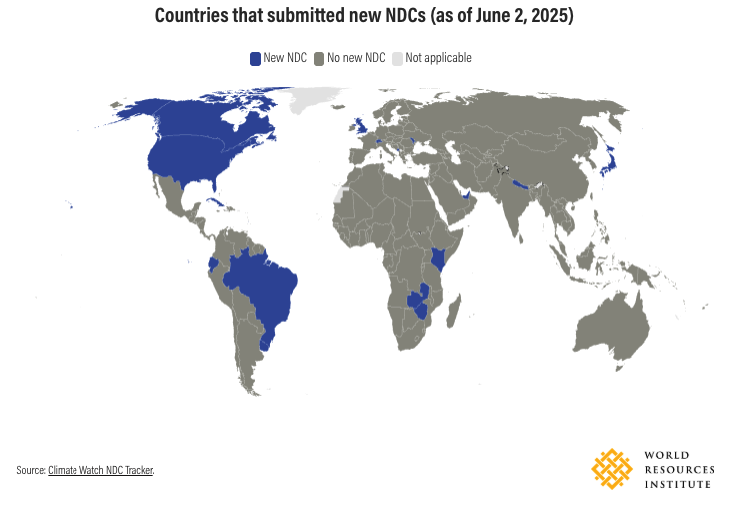

Under the Paris Agreement's timeline, 2025 NDCs were technically due in February. As of early June, only a small proportion of countries had submitted them, covering around a quarter of global emissions.

These early movers include a diverse mix of developed and developing nations from different regions and economic backgrounds.

Among the G20 — the world's largest GHG emitters — only five countries submitted new NDCs so far: Canada, Brazil, Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom. (Since submitting its NDC, the U.S. announced its intention to withdraw from the Paris Agreement.)

Several smaller and highly climate-vulnerable countries have also stepped forward, including Ecuador and Uruguay in Latin America; Kenya, Zambia and Zimbabwe in Africa; and island states such as Singapore, the Marshall Islands and the Maldives.

That means close to 90% of countries have yet to submit their new NDCs.

There are several reasons for this. The last round of NDCs was pushed back by a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, giving countries only four years to prepare new plans. Geopolitical tensions, ongoing conflicts and security concerns have further complicated progress. Many smaller developing nations are also facing capacity constraints as they work to complete biennial climate progress reports and new national adaptation plans (NAPs), also due this year.

Most countries are now expected to present their new NDCs by the UN General Assembly in September.

Compared to previous targets, the NDCs submitted so far have made a noticeable but modest dent in the 2035 "emissions gap": the difference between where emissions need to be in 2035 to align with 1.5 degrees C and where they're expected to be under countries' new climate plans.

If fully implemented, new NDCs are projected to reduce emissions by 1.4 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) by 2035 when compared to 2030. Looking only at unconditional NDCs (those that don't require international support), this leaves a remaining emissions gap of 29.5 GtCO2e to hold warming to 1.5 degrees C. When conditional NDCs (those that do require international support) are included, this gap shrinks to 26.1 GtCO2e.

Much of the progress in narrowing the gap comes from major emitters that have already submitted new NDCs — most notably the U.S., Japan and Brazil. Given their large emissions profiles, their new commitments account for the majority of the reductions seen so far.

While this marks progress, it's far from what's needed to keep global warming within safe limits. Getting on track to 1.5 or even 2 degrees C would require much steeper cuts than what's currently on the table.

However, this is not the full picture.

Many of the world's largest emitters have yet to submit their 2035 targets. The remaining G20 countries alone account for about two-thirds of global GHG emissions. This makes their forthcoming NDCs especially important: The scale and ambition of these commitments could meaningfully narrow the emissions gap — or, if they fall short, leave the world locked into a trajectory that puts global temperature targets out of reach.

Among the countries that have submitted new NDCs so far, the United Kingdom stands out for its ambitious climate trajectory. Following the recommendations of its Climate Change Committee, the U.K. has set a bold target to reduce emissions 81% by 2035 from 1990 levels. This rapid decline in the coming decade would put the country on track toward its net zero goal by 2050, based on realistic rates of technology deployment and ambitious but achievable shifts in consumer and business behavior.

Other countries, such as Japan and the United States, have opted for a "linear" approach toward net zero — meaning if they drew a straight line to their net-zero target (for example, 0 GtCO2e in 2050), their 2030 and 2035 targets would fall along it, reflecting a constant decline in emissions each year. Japan aims to cut emissions 60% from 2013 levels by 2035, while the United States has pledged a 61%-66% reduction from 2005 levels by 2035.

Despite the U.S. withdrawing from the Paris Agreement, undermining climate policies and attempting to dismantle key government institutions, its NDC target may still provide a framework for climate action at the state, city and local levels, as well as for future administrations. Many of these entities have already rallied around the new NDC and are committed to making progress toward its targets.

However, the linear approach Japan and the U.S. are taking to emissions reductions — as opposed to a steeper decline this decade — risks using up a larger share of the world's carbon budget earlier and compromising global temperature targets.

Brazil presented a broader range of emissions targets in its NDC, committing to a 59%-67% reduction by 2035 from 2005 levels. These two poles represent a marked difference in ambition: A 67% reduction could put Brazil on track for climate neutrality by 2050, while a 59% reduction falls short of what's needed to meet that goal. It is unclear which trajectory the government intends to pursue, leaving Brazil's true ambition in question. The NDC also omits carbon budgets for specific sectors (such as energy, transport or agriculture), which would clarify how it plans to meet its overarching emissions goals. However, Brazil committed within its NDC to develop further plans outlining how each sector will contribute to its 2035 target.

Elsewhere, Canada made only a marginal increase to its target, shifting from a 40%-45% emissions reduction by 2030 to 45%-50% by 2035 from 2005 levels. This falls short of the recommendation from Canada's own Net-Zero Advisory Body, which called for a 50%-55% reduction by 2035 — and warned that anything below 50% risks derailing progress toward the country's legislated net-zero goal by 2050. While every increase in ambition counts, such incremental changes do not match the urgent pace of progress needed among developed and wealthy economies like Canada.